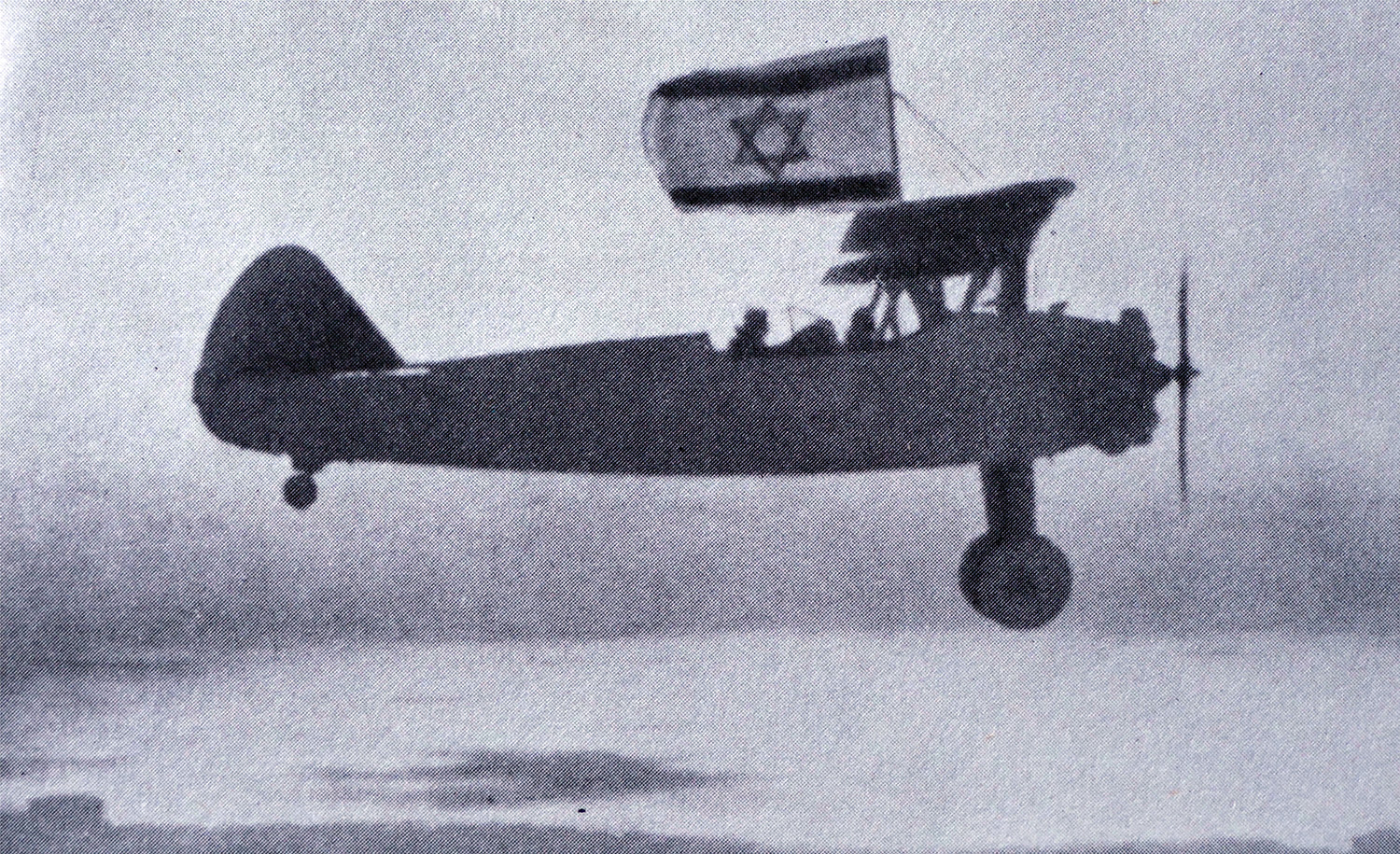

An early Israeli aircraft during the War of Independence in 1948. Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

This is the fifth installment in the historian Martin Kramer’s series on how Israel’s declaration of independence came about, and what the text reveals about the country it brought into being. Previous installments can be seen here.—The Editors

“Our tragedy is that we always have to explain ourselves.” Thus complained Mordechai Ben-Tov of the left-wing Mapam party, quoting Chaim Weizmann, at a meeting of the People’s Administration on May 13, 1948, the day before the prospective Jewish state was to declare its independence. The purpose of the meeting was to debate the declaration’s latest draft.

In Hebrew, this sort of “explaining” is sometimes called hasbarah—justifying one’s actions in an effort to win hearts and minds. David Ben-Gurion, presiding over the May 13 meeting, approached the declaration as at least in part an exercise in such hasbarah, and said so explicitly:

This has to be a document that includes profound, encompassing, and fundamental Zionist hasbarah, both for the Jews—because there are still many Jewish doubters—and for the non-Jews who are not our haters. There’s no place for juridical argumentation—the document has to set forth political assumptions.

Given the weight that would later be borne by the declaration—it would come to be referred to as Israel’s domestic “identity card” and even as a source of law—these words might seem surprising. But Ben-Gurion couldn’t have known that the declaration would serve so many unintended purposes. The next day, only hours before independence was officially proclaimed, he would again urge his Zionist partners not to get tied up in details—because this was just a declaration:

There is no one among its drafters who thinks it’s the height of perfection. But the purpose was to give just those things that in our opinion provide a basis for what we’ll do today, for the people of Israel, world opinion, and the UN. We’re declaring independence, nothing more. This isn’t a constitution.

Indeed, in light of that purpose, much of the drafting revolved around what sorts of statements and justifications worked best for external audiences. One justification, discussed in last month’s installment, was the identification of Eretz-Israel as the birthplace of the Jewish people. Ben-Gurion made sure that was included, albeit in a national rather than a religious form. This left three other rationales: first, the past sufferings of the Jews during their millennia of life in exile from the land; second, the modern achievements of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine; and third, the licenses issued by the international community over preceding decades in the form of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the 1922 League of Nations’ conferral of the mandate of Palestine on Great Britain, and above all the United Nations “partition resolution” of November 1947.

Each of these justifications had some use, and some merit. But the declaration had to be brief, and choices had to be made. Those choices said much about the sensibilities of the drafters; they also said a great deal about the politics of that specific moment in time.

A hierarchy of claims

Let’s begin with the sufferings of the Jews, starting with their dispersal after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 CE and climaxing most recently in the Holocaust.

In the earliest drafts, these sufferings loomed large. The first, drawn up by the lawyer Mordechai Beham, had been much influenced by the American Declaration of Independence, whose “list of [King George III’s] abuses and usurpations” takes up more than two-thirds of that document. Beham’s draft, for its part, catalogued “the destruction of our Holy Temple in Jerusalem” by the Roman legions, the banishment of the Jews into exile and “the loss of life and property at the hands of their many oppressors such as no people has been called upon to endure since time began,” and finally the “cruel extermination of one third of our people” in the Holocaust.

Later drafters cut most of this, leaving only the mention, from pre-modern history, of the Jews’ forcible exile from their land and, from modern history, of “the catastrophe which recently befell the Jewish people—the massacre of millions of Jews in Europe.” And both of these disasters would be portrayed mainly as backdrops. Even though the Jews were exiled, the people “in every successive generation . . . never ceased to pray and hope for their return . . . and for the restoration of their political freedom.” As for the contemporary remnant of Jewry in Europe, the survivors of the Holocaust, they, too, “never ceased to assert their right to a life of dignity, freedom, and honest toil in their national homeland.”

But would this rationale, however persuasive for Jews, also persuade the world? Even if in the past Jews had been exiled, persecuted, and most recently exterminated, did this necessarily point to the requirement of a Jewish state? It is often said that the Holocaust led to the creation of Israel, but Ben-Gurion warned that minds less favorably disposed might draw a wholly different conclusion: the people for whom a Jewish state had been designed were gone, so where was the need for such a state now, especially since creating it would mean provoking Arab rage? Therefore, Ben-Gurion said, important as it was to emphasize “historic rights,” and to evoke the Holocaust, it was not enough.

Moreover, even as the drafters were shifting from one rationale to another, in Washington the Truman administration was backtracking. The State Department argued that dividing the land, as proposed by the UN, was unworkable, and that the League of Nations mandate, due to expire on May 14, should be replaced instead by a UN trusteeship. To dissuade Americans on this front, the Zionists would need more than a catalogue of historical rights and grievances; they would need a different rationale.

In the latest draft, the work of Moshe Shertok (later Israel’s first foreign minister), that two-part rationale became clear: first, there was a Yishuv in place that was ready for statehood and primed to fight for it; second, a prime element in the UN’s November 1947 partition resolution was the grant of an “irrevocable” license for a Jewish state.

The case for the self-sustaining capacity of the Yishuv was made strongly in a paragraph hailing the “pioneers, immigrants, and defenders” who

made deserts bloom, revived the Hebrew language, built villages and towns, and created a thriving community controlling its own economy and culture, loving peace but knowing how to defend itself, bringing the blessings of progress to all the country’s inhabitants, and aspiring toward independent nationhood.

This was a fairly straightforward claim, and it had the added virtue of echoing the findings of the UN commission (UNSCOP) that, in recommending partition in 1947, approvingly described the Yishuv as “a highly organized and closely-knit society which, partly on a basis of communal effort, has created a national life distinctive enough to merit the . . . title of ‘a state within a state.’” Moreover, Shertok’s draft claimed, during World War II the Yishuv had, “by the blood of its soldiers and its war effort, gained the right to be reckoned among the peoples who founded the United Nations.” By rights, then, one might argue that, having fielded soldiers in a “war effort,” the Yishuv should have already been recognized as a state—and as a founding member of the UN itself!

All in all, perhaps the most forceful single argument for the Jewish state was the fact that by 1947 the Yishuv, in the words of Abba Eban, had become “too large to be dominated by Arabs, too self-reliant to be confined by tutelage, and too ferociously resistant to be thwarted in its main ambition.”

As for the UN’s “license,” the argument on its behalf was based on the dramatic vote, still fresh in memory, that had taken place on November 29, 1947 at a meeting of the United Nations in its then-headquarters in Flushing Meadows, New York. Then and there the General Assembly, by a two-thirds majority, recommended a plan for “Independent Arab and Jewish States” and a “Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem,” to be implemented two months after the British evacuation but no later than October 1, 1948.

Zionist diplomacy had worked full-bore to secure this “partition resolution,” as it came to be called, while the Arabs had tried to stop it. And when the resolution passed, the Yishuv hailed it as the greatest Zionist achievement since the Balfour Declaration of 1917. So it is still remembered; even today, Israel works hard to remind the world that in November 1947 the UN licensed the establishment of a Jewish state. But in April and May 1948, things looked different, and there was a debate among the leadership of the Yishuv over whether, and to what extent, the UN resolution could actually be relied upon.

Needless to say, Ben-Gurion and many others harbored deep reservations about key aspects of the UN plan. According to it, Jerusalem, home to 100,000 Jews, a sixth of the Yishuv, would be placed under some sort of international regime, while the dream of a state in all of Palestine would have to be shelved since half of the country was slated to become an Arab state. Although the mainstream Zionist leadership formally accepted the plan in its totality, the general attitude was well expressed by Ben-Gurion years later:

We were resigned in 1947 to receiving the rump end of Palestine in accordance with the United Nations settlement [that is, the partition plan]. We didn’t think that settlement very fair since we knew that our work here deserved a greater assignment of land. We didn’t, however, press the point and prepared to abide scrupulously by the international ruling come the day of our independence.

Indeed, since the passing of the UN resolution, much had happened to weaken the Yishuv’s commitment to it. The Arabs, following their own rejection of the plan, had launched a civil war against the Jews, in the course of which the Jews soon got the upper hand—to the extent of taking areas allotted to the Arab state that had become bases for Arab attacks on the Yishuv. Most notably, this included Jaffa, just minutes from the Tel Aviv meeting place of the People’s Administration.

Matters were thus in flux, and some thought it might even be possible to step back from total acceptance of the UN plan. True, in any declaration of independence it would have to be mentioned—since, of all the justifications for declaring the Jewish state, the UN vote was accepted by, and carried the greatest weight in, the outside world. But could it be invoked in such a way as to legitimize the Jewish state but not bind the state to all of the plan’s provisions? In particular, there was the issue of the map that accompanied the plan: would it be possible to get out of the straitjacket it placed on Israel’s freedom of maneuver?

On these points, much can be learned by examining successive drafts of the declaration. From the beginning, so strong was the attachment to the UN resolution that early drafts not only regularly invoked it but referred to it explicitly as a “partition” plan and pledged explicitly to uphold its accompanying map. But by May 12, two days before the declaration, the People’s Administration reopened discussion. Did the Jewish state need to be declared, for instance, in the framework of the plan? Although that was the formula most likely to win international recognition, it also posed a dilemma by implying acceptance of the map. On the other hand, a declaration that the state was established simply on the basis of the plan could raise objections by implying a diminished commitment to the map. In brief, should the Jews seek to reassure the international community that they weren’t bent on expansion, or prepare the case for possible additions of territory?

In April, the jurist Felix Rosenblueth, a member of the People’s Administration who would later become Israel’s first minister of justice, had assumed responsibility for overseeing the draft declaration. In the May 12 session, he now insisted that the state be declared “in the framework” of the UN partition plan—and that its borders be defined accordingly. As a matter of law, he contended, “it is impossible not to treat borders.” Anticipating discussion, he had distributed in advance a proposed draft declaring “a free, sovereign Jewish state in the borders set forth in the resolution of the UN General Assembly of November 29, 1947.”

Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, a lawyer and judge (and future minister of police), supported Rosenblueth with a legal argument of his own:

Regarding borders, I agree with Rosenblueth. It’s not credible to declare an authority without defining its scope. This can draw us into complications. . . . What the state publishes is the law in the territory of the state. . . . When a state arises, it declares the limits of its borders.

In previous installments I’ve noted that Ben-Gurion hadn’t devoted a great deal of time to the People’s Administration discussions. But he had to stay engaged, precisely because he couldn’t rely on others to appreciate the full political implications of their formulas. For better or worse, the drafting had been turned over to lawyers, and the result was exactly the kind of overly-lawyered thinking that he was on guard to check. As he saw it, Rosenblueth’s team was about to confine the state to the same geographical straitjacket from which it had already managed to wriggle free, and to throw away the hard-earned gains of weeks of battle, not to mention the prospect of gaining a foothold in Jerusalem.

In a rebuttal described by one witness as “trenchant,” Ben-Gurion now took strong exception to the arguments of Rosenblueth and Sheetrit. “If we decide not to say ‘borders,’” he asserted plainly, “then we won’t say it.” Nor was there any legal requirement to specify them. To illustrate, he drew a compelling comparison:

This is a declaration of independence. For example, there is the American Declaration of Independence. It includes no mention of territorial definitions. There is no need and no law such as that. I, too, learned from law books that a state is made up of territory and population. Every state has borders. [But] we are talking about a declaration [of independence], and whether borders must or mustn’t be mentioned [in one]. I say, there is no such law. In a declaration establishing a state, there is no need to specify the territory of the state.

Ben-Gurion went farther. The UN, having done nothing to implement its plan, and the Arabs, having declared war on Israel, had effectively torn up the UN map; in these circumstances, expansion beyond the partition borders would be entirely legitimate:

Why [should we] not mention [borders]? Because we don’t know [what will happen]. If the UN stands its ground, we won’t fight the UN. But if the UN doesn’t act, and [the Arabs] wage war against us and we thwart them, and we then take the western Galilee and both sides of the corridor to Jerusalem, all this will become part of the state if we have sufficient force. Why commit ourselves?

Ben-Gurion then did something unusual for him: he called for a vote. “Who favors including the issue of the borders in the declaration?” Four raised their hands. “And who is opposed?” Five. “Resolved,” read the minutes, “not to include the issue of the borders in the declaration.”

It was the narrowest of margins, and one vote could have tilted it the other way. What prompted Ben-Gurion to call for a vote is a matter of conjecture, but clearly he regarded the issue as of cardinal importance and probably also thought he had to break the momentum built by Rosenblueth, a formidable legal authority.

Nor had Rosenblueth’s been a lone voice. The Jewish Agency had reassured foreign governments that the new state wouldn’t deviate from the partition map, and its officials, as the U.S. consul in Jerusalem reported the following day, “have steadfastly maintained their intention to remain within the UN boundaries.” If this “intention” were to make its way into Israel’s foundational document, it would be impossible to amend later.

Where exactly might the Jewish state seek to adjust the borders stipulated by the partition plan? Ben-Gurion mentioned inclusion of the western Galilee and the Jerusalem corridor, but these were only two examples. In recalling his rationale in later years, he would emphasize its more general character:

I said: let’s assume that during a war we capture Jaffa, Ramlah, Lydda, the Jerusalem corridor, and the western Galilee, and that we want to hold onto them. Well, it just so happens that we did take these places!

In brief, Ben-Gurion wanted the vote as a license to incorporate any strategically vital territory seized in a war with an Arab aggressor.

In the early afternoon of May 14, with little time left before the release of the declaration, Ben-Gurion presented the final draft for approval by the People’s Council, a larger body than the People’s Administration. Mention of borders had disappeared from the draft, but since the decision to omit them had been carried by a narrow vote, there was some chance that the issue might now become a last-minute bone of contention. To forestall the possibility, Ben-Gurion placed an unexpected spin on the May 12 decision:

There was a proposal [in the People’s Administration] to determine borders. And there was opposition to this proposal. We decided to sidestep this question (I use this word deliberately), for a simple reason: if the UN upholds its resolutions and commitments and keeps the peace and prevents bombing and implements its resolution forcefully—we, for our part (and I speak on behalf of the entire people), will respect all of its resolutions. Until now, the UN hasn’t done so, and the matter has fallen to us. Therefore, not everything obligates us, and we left this issue open. We didn’t say “No to the UN borders,” but we also didn’t say the opposite. We left the question open to developments.

This was a masterstroke of wording. In fact, the question of whether to commit the new state to the partition borders hadn’t been sidestepped at all; it had been decided by a vote, albeit a vote that replaced certainty with ambiguity. Until May 12, the state-in-waiting had been committed to the partition map. After May 12, that commitment depended on the UN’s doing something it should have done but hadn’t done and likely wouldn’t do. Ben-Gurion had created a new consensus—“of the entire people”—suggesting that the partition map might be revised. And so, when he read out the declaration later that day, the borders had gone missing.

There’s an American aspect to this part of the story. The world had been led to expect that Israel would fill only the space on the map allotted to it by the partition plan. Washington was no exception; as Jewish statehood drew near, the U.S. government sought reassurances.

Thus, on May 13, Eliahu Epstein (later Eilat), the Jewish Agency’s “ambassador” to Washington, received a phone call from Clark Clifford, special counsel to President Truman and a keen supporter of Zionism. Clifford was working to persuade Truman to recognize the Jewish state immediately upon its birth. He instructed Epstein to write the president formally with this request.

Clifford would later recall emphasizing to Epstein the particular importance of the new state’s claiming “nothing beyond the boundaries outlined in the UN resolution of November 29, 1947, because those boundaries were the only ones which had been agreed to by everyone, including the Arabs, in any international forum.” This was an odd claim, since the Arabs hadn’t accepted a Jewish state in any borders; but the demand being placed on Israel was clear enough, and in his letter to the president Epstein duly wrote that Israel was being declared “within frontiers approved by the [UN] General Assembly.” Washington’s de-facto recognition of the state followed almost immediately.

In reality, as we’ve seen, the state of Israel hadn’t been declared in any borders. This would later give critics a basis on which to claim that the United States had been misled into recognizing the state based on a false representation. But in writing his letter Epstein wasn’t aware that Ben-Gurion had shifted Israel’s position. On May 14, Tel Aviv was totally absorbed in the political and practical preparations for the declaration, and Epstein had no contact with Shertok, who was his superior. He would apologize to Shertok that same day, but only for writing to Truman on his own initiative.

So Israel received Washington’s recognition as a state without borders, although Washington may well have assumed otherwise. Within a week, however, the declaration’s lack of a reference to borders had been noticed and was causing trouble at the UN—and Abba Eban, then representing the new state’s interests at the world body, anxiously urged that the omission be rectified. On May 24, he sent a message to Shertok from New York:

Ambiguity in [independence] proclamation regarding frontiers much commented [upon by] delegations and exploited [by] opponents, possibly delaying recognition and restricting those received. We urge official statement defining frontiers [of] Israel in accordance with November [1947 UN] resolution.

This, from the man who would become Israel’s most famous champion in the world. Needless to say, Eban’s plea fell on deaf ears—fortunately so, as most Israelis today would agree. By the end of the 1948-1949 war, Israel’s territory had grown from the share allotted to it under the partition plan—55 percent of mandatory Palestine—to 78 percent: that is, by nearly 50 percent. The additional territory included west Jerusalem, a corridor leading to Jerusalem, the southern approaches to Tel Aviv including Jaffa, Lydda, and Ramlah, the whole of the Galilee, and parts of the Negev.

The “partition” dilemma

It might be thought that while the declaration didn’t commit Israel to borders, it did commit Israel to the principle of partition itself. Recall that according to the UN plan there were to be two states, one Jewish and one Arab, and an economic union between them.

The pertinent article in the declaration reads as follows:

THE STATE OF ISRAEL is prepared to cooperate with the agencies and representatives of the United Nations in implementing the resolution of the General Assembly of the 29th November, 1947, and will take steps to bring about the economic union of the whole of Eretz-Israel.

This article, too, had undergone revision. As late as Shertok’s May 13 draft, the UN plan was being described by its official name: “Plan of Partition of Palestine with Economic Union.” In the session that day, Ben-Gurion insisted on deleting the reference to partition. “Why should we mention partition?” he asked pointedly, and so that word, too, disappeared. The declaration does emphasize that the UN had “passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel,” and even insists that this decision was “irrevocable.” But from this alone one might conclude that the General Assembly had voted in favor of only one state, a Jewish one, which by itself would pursue the economic union of the whole country.

Why was Ben-Gurion adamant about omitting the words “partition plan”—a plan he had supported back in 1937 when it was recommended by a British Royal Commission and again ten years later in the November 1947 UN resolution? The reason was simple: to make the declaration acceptable to the Revisionist right, whose representatives might resist signing a document with the word “partition” in it. And they were indeed sensitive to that word and its connotations. In the People’s Council meeting on the morning of the declaration, the Revisionist representative Herzl Rosenblum, also known as Vardi, spoke up to register his ongoing worry. Despite the fact that everything possible had been done to avoid mentioning partition, the declaration, he said, still promised to “take steps to bring about the economic union of the whole of Eretz-Israel.” Could not this be construed as acceptance of partition? After all, what was to be unified, if not two separate entities? To mention “economic union” was thus to imply acceptance of “the principle of partition.”

Shertok gave a peculiar answer:

It’s one or the other: either we rest on the UN decision, or we don’t. If we do rest on it, we have to rest on all of its principal parts. In the [1947] resolution, there is an explicit condition: for the Jewish state (and the Arab state) to earn UN recognition, it must be clear that it is prepared to enter into an economic union.

In fact, however, Ben-Gurion’s position was precisely the opposite of “either one or the other.” To him, rather, Israel could play up UN recognition of the Jewish right to a state while pretty much ignoring the map and finessing the union. The latter was especially easy to do since in any case no Arab state had been established. And indeed, as we see today, the economic integration of the whole country doesn’t require that there be two states.

The UN’s limited role

In the May 13 meeting of the People’s Administration, some of the members complained that Shertok’s draft was too full of justifications. Mordechai Ben-Tov of Mapam, who (as we saw early on) complained about the Jewish impulse to “explain ourselves,” thought that “so much detail . . . weakens a declaration” and that “it would be better if it were shorter.” In particular, he didn’t like all of the references to international decisions:

It makes no sense in this historic moment to base everything on this or that provision of the [League of Nations] mandate or the UN resolution. Our historic right drowns in a multitude of passages, and I don’t find an expression of the natural right of a people to a free life in our homeland.

Rabbi Judah Leib Fishman, quoting the Talmud, agreed: “Only that which is unclear requires many proofs.”

Ben-Gurion also agreed that Shertok’s draft was too long, and that night he cut it. But his changes were mostly stylistic; he was careful to leave in place the core justifications, including the references to the UN plan. In fact, the world body appears in no fewer than six separate paragraphs of the declaration.

Later, Ben-Gurion would claim that the UN had done nothing to establish the state, that it came into existence by force of arms alone, and that the UN resolution was a dead letter—“void,” as he put it in 1949 when he moved Israel’s capital to Jerusalem. But that was after the war. On May 14, 1948, Israel’s founders wanted to emphasize to the world that while the Jewish people had been born in Eretz-Israel, its state was the adopted child of the United Nations. Israel had a “natural and historic” right to exist, and that right had been recognized by the world.

Nothing made this point more clearly than the crucial passage of the declaration:

By virtue of our natural and historic right and on the strength of the resolution of the United Nations General Assembly, we hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.

Does this suggest that the United Nations “created” the state of Israel? Hardly; if it were within the power of the UN to create states, an Arab state would have arisen in 1948 alongside Israel. After all, the Arabs of Palestine possessed exactly the same recognition of their rights and the same license to act as did the Jews. The difference, to revert to the term invoked by the UN Special Committee on Palestine, was that the Arabs didn’t constitute a “state within a state.”

I have made much use in this series of the protocols of the People’s Administration and the People’s Council. Both were established by the Zionist Executive in order to bring together all factions in a nascent government and parliament. The Jews had made common cause, and with it created the institutions needed to translate their rights and recognition into statehood. The Arabs of Palestine had nothing comparable. Indeed, their elites were already in full flight from the country.

The most impressive part of the Israeli declaration is perhaps the simplest: “We, members of the People’s Council . . . ” Through these representatives, who affixed their signatures in tidy alphabetical order on the proclamation that created the state, the new Israeli people spoke as one.