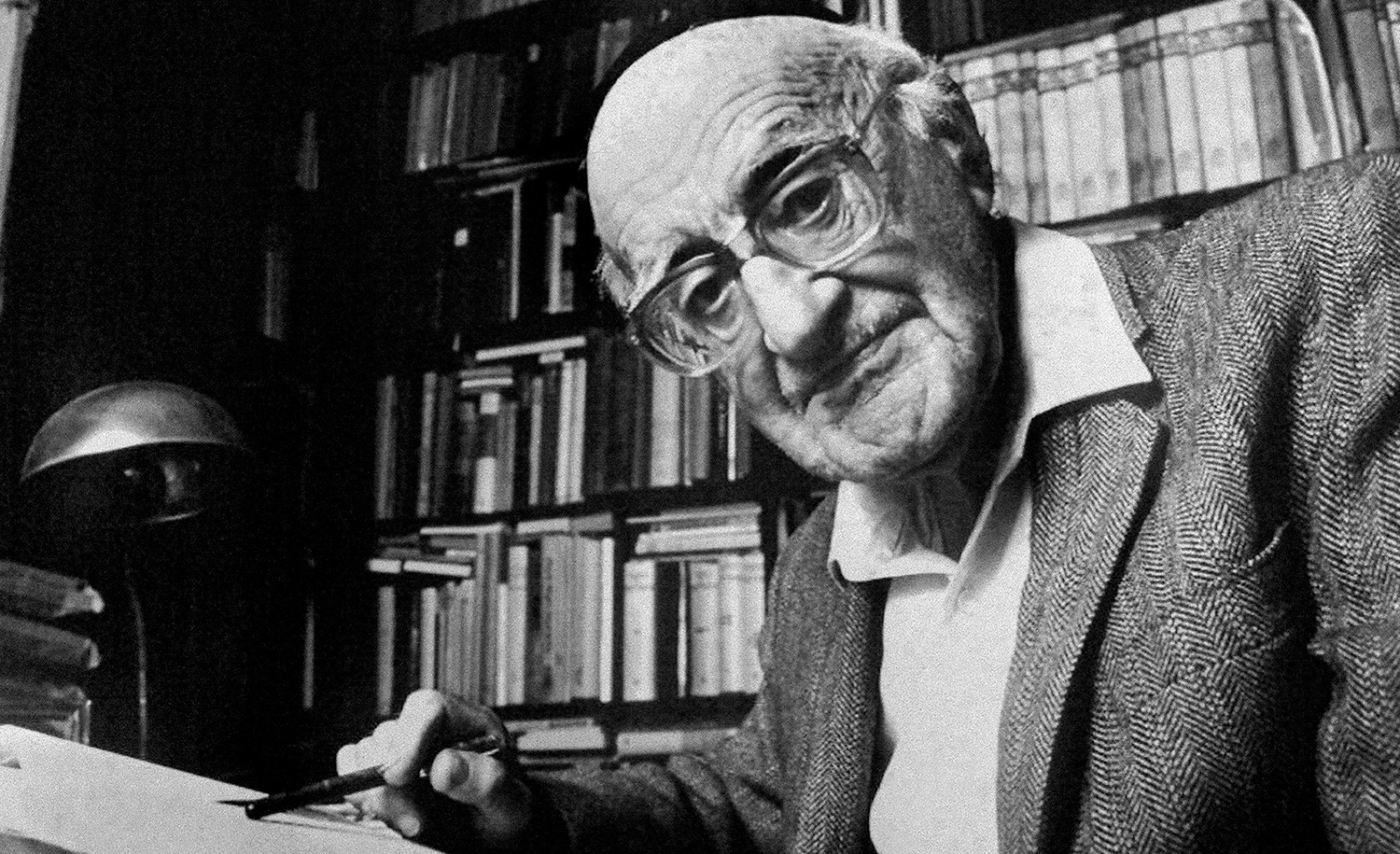

It was July of 1967 and the clean-shaven Yeshayahu Leibowitz of the Hebrew University wore a kippah. Yes, a kippah adorning the head of a biochemist, talmudist, philosopher, and medical doctor, a Riga-born Jew keeping the Sabbath, the dietary laws, etcetera, a Zionist by way of Berlin, Heidelberg, and German-speaking Switzerland. His lantern jaw was familiar in the small town Jerusalem was then, especially in the Rehavia neighborhood where the yekkes at the university—the German-speaking Jewish refugees—made their homes. Leibowitz was not a yekke himself but an Ostjude, from the East. Still, you couldn’t ignore the Berlin and Basel degrees, or his wife Greta, herself a PhD in mathematics, a yekkit from North Rhine-Westphalia. Not an unimpressive couple.

The derivation of the word? Some believed yekke referred to the German Jewish habit of wearing jackets and ties in the Middle Eastern heat. Others insisted it was acronymic for Y’hudi kasheh havanah—dimwitted Jew.

Be that as it may Kranzdorf remembers his own father as a yekke, an atheist, a Wagner-besotted, non-Zionist refugee who always wore a jacket and never went tieless in the Middle East. He would salute Leibowitz on King George Street. He also thought of his own refugee mother chatting in German with the Frau Professor in Shemtov’s vegetable and fruit stand at the corner of Aza Road and Radak Street. Greta with a pram—if Kranzdorf was Ernst’s and Dora’s only kid, the Leibowitzes had six children. Pru ur’vuh—be fruitful and multiply, as the Torah commands. Leibowitz the husband, father, and commandment-keeper was regularly seen in the neighborhood by Kranzdorf in boyhood. In retrospect, he noticed Leibowitz carried himself as a good and an observant Jew; noticed, that is, in contrast to Kranzdorf himself, now a father of two, a bad Jew who, a few years previous, was committing adultery and writing his MA thesis on Kafka. He’d see Leibowitz walking fast between Rehavia and the campus at Givat Ram and overhear him talking to himself.

It was to Givat Ram that Kranzdorf, who’d gotten a medal for what he’d done on the Golan Heights, and nurse Esther who’d worked overtime with casualties, went to hear him speak a month after the Six-Day War.

Standing room only, and Leibowitz in black turtleneck, black trousers, black shoes, and black yarmulke pacing the stage with a microphone on a cord skinning the Jews alive like nobody so much as Ezekiel. Unlike with the prophet, however, there wasn’t a word against foreigners or any hope of mercy or deliverance. Had pre-war dread turned into rapture overnight? Delusions! The miraculous victory of the IDF shouldn’t be celebrated but lamented, the figure pacing the stage like a panther snarled. All right, not the overrunning of the Sinai or the Golan but of Gaza and the West Bank, call it Judea and Samaria if you like, of areas containing two million hostile foreigners, and of the other half of Jerusalem containing a pile of stones known as ha-Kotel ha-ma’aravi, the Western Wall. There are no holy places in Judaism! To believe and act as if there were would be to practice avodah zarah, idolatry.

The taking of Gaza and the West Bank was a calamity, not a miracle. Due to it the so-called Jewish state would become a colonial regime and the IDF an occupying army, corrupt, degenerate and weak, jailing or deporting those Arabs who resisted and enlisting quislings from among the others while funneling the best Israeli young men into the secret police.

“Ha-tovim l’Shabak!” cried Leibowitz, meaning “The best to the General Security Services,” ringing a change on the well-known expression, “ha-tovim l’Tayis,” meaning “The Best to the Air Force.” Every word bitten off and spat out. And every half-foreign, half-Hebrew portmanteau word of his coinage too, such as Diskotel, a mash-up of discotheque and kotel. The government-sponsored, taxpayer-supported rabbinate would be complicit in all this, he forecast. And why shouldn’t it be? It was the godless government’s pilegesh, its kept woman. The so-called “liberation” of Jerusalem, Hebron, Bethel, Shechem, the venues of the Bible and the red-hot heart of the Promised Land? “Hark the footsteps of the Messiah!” Leibowitz taunted.

“Redemption Now!”

Kranzdorf attended closely but not so closely as to miss Greta sitting in the front row beside Marcel-Jacques Dubois in his cassock. Dubois, a Dominican who’d hidden Jewish kids from the Vichy police, a so-called ḥasid umot ha-olam, a Righteous Gentile, was a colleague of Leibowitz’s in the philosophy department and even known to be his friend, having repudiated the doctrine according to which Christianity supersedes Judaism. Yes, a Dominican with tenure at the Hebrew University who six years later would be naturalized as an Israeli citizen. He was a friend of the Jews who before his life ended would have second thoughts and move from Rehavia to an Arab, Palestinian village on the outskirts.

There was Greta, and Frère Dubois, and other Jerusalemites familiar to Kranzdorf—immigrants, refugees like himself and sabras like Esther, a standing-room-only crowd of pacifists, Trotskyites, Stalinists, liberals, Zionist humanists, and the merely curious. Overwhelmingly they were pig-eaters and Shabbat-violators like Kranzdorf and Esther, but if he wasn’t the only Jew in khaki his wife was the only Sephardi.

“Hark the Messiah cometh!”

That was Leibowitz’s style—withering, not Socratic. Over the years Kranzdorf had heard him interviewed on Galei Tsahal, the Israel Defense Forces radio network, about every topic under the sun.

Eichmann? The man should’ve been set free! He wasn’t responsible, you understand, he was the product of Christianity the entire mission of which has always been, is, and will always be, to supersede the killers of God.

Disbelief in God following Auschwitz? If you disbelieve now you never believed!

Wagner? A terrific composer Leibowitz enjoyed at home, particularly Tristan und Isolde, and violently anti-Semitic—so what?

Zionism? Nothing more than the Jews taking responsibility for themselves.

But of course Galei Tsahal hadn’t broadcast his thoughts about what Unit 101 of the IDF had done at Qibye in ’53. Only in print, only in a small-circulation magazine had Kranzdorf read Leibowitz’s views on the reprisal, fourteen years earlier, in a village just over the Green Line, for the murder of a young Sephardi woman and two of her children by infiltrators. A premeditated massacre of noncombatants, Leibowitz called the operation authorized by David Ben-Gurion. What could’ve driven the Jewish boys and men guilty of this atrocity? The answer: more avodah zarah, the notion that they were educated to prioritize state security over God. Unit 101 was commanded by Ariel Sharon and included as its youngest member Rehavia’s own Chaim Kranzdorf. Did Leibowitz know that Kranzdorf had participated? Maybe, maybe not. His name was unmentioned in the little magazine, and if he’d only ever said hello to the man, Leibowitz had only ever grunted back.

Having made his remarks he took questions. Somebody asked what he proposed be done. Should we just get out? What about holding these cards until exchangeable for peace? No, no, Leibowitz yelled. “Peace is just another delusion! There’ll never be peace! Forget it and immediately get out especially from Judea and Samaria.” What? Even the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem? “Yes, even that!” Of course the Jews were going to be too wickedly foolish to do any such thing. And other questions including one too foolish to merit a verbal response. It was posed by a kid, a blemish-faced high-schooler wearing the knitted yarmulke of those Sabbath-keepers who’d be establishing the settlements. He asked what Maimonides has to say on voluntarily leaving any part of Eretz Yisrael, to which Leibowitz’s answer was a gesture as if brushing off a fly.

A memorable evening. Leibowitz whipping the Jews, and the bad Ashkenazi Jews who’d come relishing. Only a few protested or heckled. Not a word or a sign from Esther, the mother of Kranzdorf’s two children, both girls, until they were back in a night scented with pine, jasmine, and a touch of honeysuckle as summer nights in Jerusalem used to be. There she judged Leibowitz harshly for batting away that pimply kid’s question. Unforgivable. A showman ensconced in his ivory tower, learned, amusing, but otherwise useless was this hard and irreligious Sephardi woman’s verdict.

More about: Fiction, Israel & Zionism