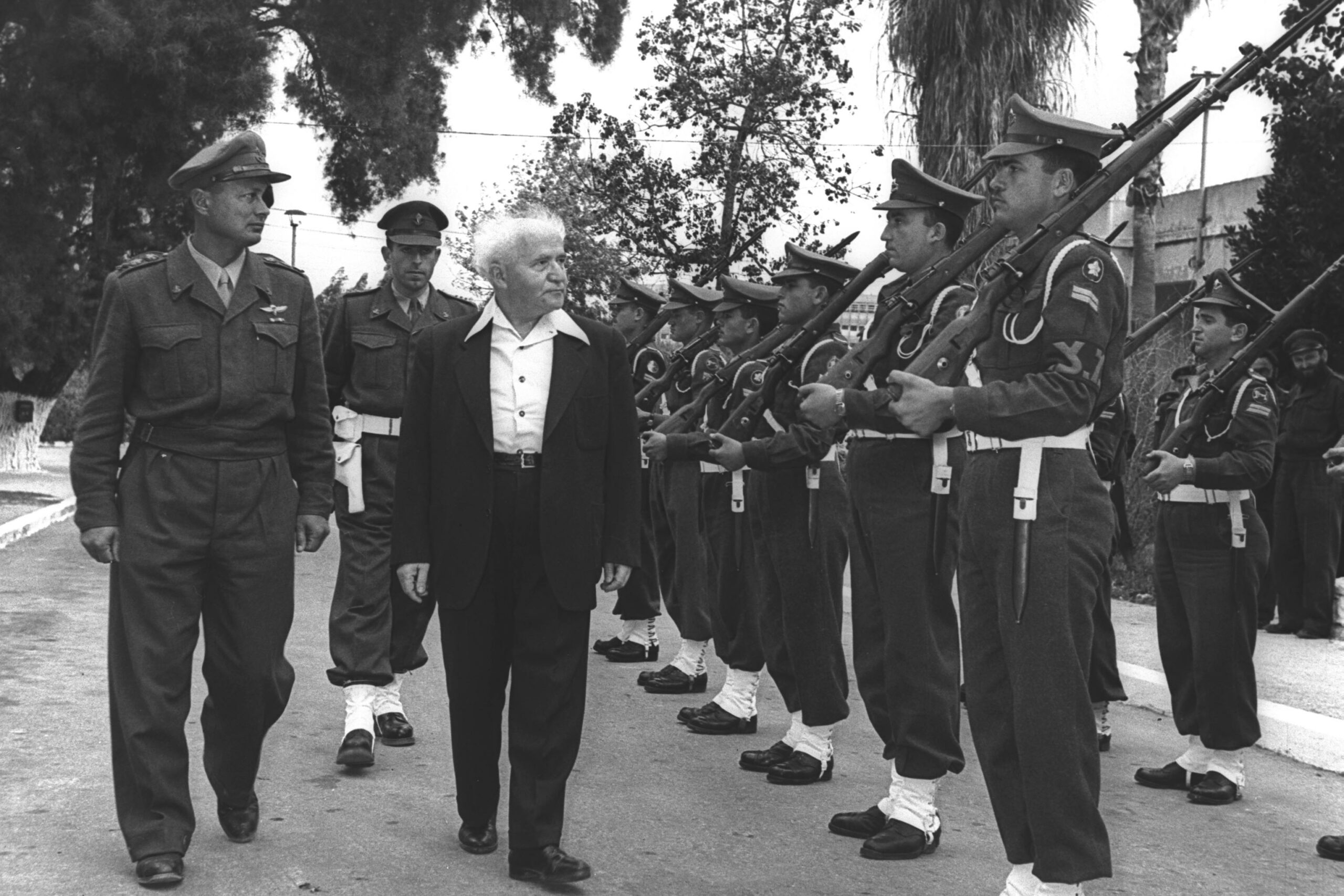

David Ben-Gurion, accompanied by Moshe Dayan, inspecting a guard of honor outside his office in Tel Aviv in 1955. HANS PIN/Israeli National Photo Collection.

On May 1, 1940, David Ben-Gurion, leader of the Jewish Agency Executive in Palestine, arrived in London for what was supposed to be a brief visit. Ten days later, Hitler invaded France and the Low Countries and Winston Churchill became prime minister. Knowing that Churchill had long been friendly to the Zionist cause, Ben-Gurion decided to stay in London, hoping to persuade the new government to raise a Jewish army in Palestine.

Ben-Gurion’s ten-month stay in London over 1940-41, which spanned the Battle of Britain and the stormiest days of the war, was a political failure. The Jewish Brigade would not get going until 1944. And Chaim Weizmann, the British Zionist leader, mostly excluded Ben-Gurion from diplomatic efforts with Churchill and other British politicians. But these months in London were crucial for Ben-Gurion’s political education. As the bombs fell, for perhaps the first time in his life, he had ample free time. He read Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek classics day and night while furiously studying Greek grammar. And though Ben-Gurion did not personally interact with Churchill, he watched his statesmanship closely.

Ben-Gurion’s admiration for Churchill knew no bounds: “How blessed is this nation, which was granted such a leader at a fateful hour,” wrote Ben-Gurion in a letter to his wife Paula. With an acolyte’s zeal, he studied Churchill’s rhetoric, copying whole passages into his diary. The “We Shall Never Surrender” speech, given after Dunkirk, struck a particularly deep chord. Ben-Gurion praised Churchill for candidly acknowledging that the Allies had suffered a “colossal military disaster” in France and Belgium: “Only a great man who believes in his strength can allow himself to say such bitter words—and before the entire nation.”

Less than ten years later, in the spring of 1948, Ben-Gurion’s own Churchillian moment would come. The British Mandate authority that had ruled Palestine since 1917 had largely packed up, leaving chaos in its wake. The war between Arab militias and the Yishuv had been ongoing ever since the United Nations had approved the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states the preceding November. And there was every expectation that regular Arab armies, including the well-trained Transjordanian Arab Legion staffed by British officers, would attack the Yishuv after the end of the British Mandate on May 15.

The outmanned and outgunned Yishuv needed money and weapons. It needed support from Zionists abroad and the Jewish Diaspora. Above all, though, it needed a recognized single chain of command to supplant the competing and overlapping institutions and cliques that had always vied for authority since Herzl’s day. In the spring of 1948, this was not merely inefficient but dangerous. To win the war, the Jews needed a central government. And, in April 1948, Ben-Gurion and his allies created that government from within the existing structures of the international Zionist movement.

What follows is a translation of David Ben-Gurion’s April 6, 1948 speech to the delegates of the Va’ad ha-Poel ha-Tzioni (variously translated as the Zionist Actions Committee or Zionist General Council) in Tel Aviv. In my view, this is both Ben-Gurion’s most stirring address from the period of the War of Independence and his most historically significant one. The speech had two goals. First, to stiffen the spines of his fellow Zionist leaders, at home and abroad, to carry on in a unified war effort. This he does through rhetoric that clearly borrows from the example (and even the language) of Churchill in 1948. But he also had a concrete political purpose: he needed a vote by the Va’ad to transfer power to a “single high authority” that had full powers to conduct politics and war on behalf of the Yishuv. In effect, in this address, Ben-Gurion calls for the World Zionist Organization to surrender the leadership role it had possessed since its founding by Theodor Herzl in 1897. Zionist business would now have to be conducted by a government.

In summoning the Va’ad to Tel Aviv, Ben-Gurion sought to address what he considered a fundamental structural problem in the Yishuv. Until 1948, the politics of the Zionist movement closely resembled the fragmented politics of the Jewish people. Power in the Zionist movement had been divided among many overlapping entities within the Land of Israel and abroad. In the Yishuv itself, there were different chains of command for military forces—a “jumble of different bodies for security issues,” as Ben-Gurion puts it in the speech—as well as for high and mundane bureaucratic and political matters. When the phrase “Zionist leadership” was uttered at home and abroad, it was not always clear whom this meant. Until the very eve of independence, U.S. officials often assumed that Chaim Weizmann remained the leader of the movement. In May 1948, Secretary of State George C. Marshall had no idea that someone named David Ben-Gurion, who for a few years had stood at the head of most of the significant bodies of the World Zionist Organization, even existed.

By the time Ben-Gurion gave this speech, he and his allies in the Mapai party had concluded that these multiple competing sources of authority could endanger the war effort and the effort to found a state. For both domestic and foreign affairs, they determined, there had to be one body with a legitimate monopoly over politics and war. This would be a provisional government, and it would be legitimate since the Va’ad ha-Poel ha-Tzioni, as the highest body of World Zionism and the political arm of the Jewish people, had authorized it.

By the end of its week-long meeting, the Va’ad had given Ben-Gurion what he sought. It authorized the creation of a “Council of 13,” a provisional executive, and a “Council of 37,” a provisional parliament. The Council of 13 would be tightly controlled by David Ben-Gurion and his labor-movement allies. The Council of 37 would be widely representative of the entire Yishuv—including both the Communists and Revisionists. Soon renamed the Minhelet ha-Am and Mo’etzet ha-Am (in English: the National Administration and the National Council, respectively), these bodies together constituted a provisional government for a nation-state-to-be.

For reasons of security, the location of the meeting—a Tel Aviv schoolhouse—was kept secret. It was an eclectic gathering, much like the many meetings of international Zionism that had taken place over the preceding 50 years. Military leaders, future prime ministers of the state of Israel, trade-union bosses, editors, rabbis, high-school teachers, hard-right American Revisionist Party academics, Zionist activists from America and across the Diaspora: around 77 leaders of worldwide Zionism assembled in Tel Aviv. The most difficult journey of all may have been the 60 miles from Jerusalem, which was under Arab blockade. That week, there had been heavy fighting in the north. The battle for Haifa was about to begin. The atmosphere was thick with tension, fear, and excitement.

Ben-Gurion’s “never surrender” rhetoric was thus entirely apropos for the occasion. Quite uniquely among modern states, the state of Israel would continue to benefit dramatically from strong international support even after it became an independent state. But from April 1948, the institutions of World Zionism that had been built by Theodor Herzl gave way to a government fit for a modern state. Herzl would have approved. For Herzl never saw world Zionism as an end in itself. He saw it as a tool toward the creation of a state. And states require governments. Through the Va’ad ha-Poel ha-Tzioni, Ben-Gurion won the right to address the fundamental questions of statecraft with which governments alone can deal.

Note: the speech has been lightly condensed: a digression on the security situation in Jerusalem and the Negev has been removed.

“Toward the Creation of a ‘Single Highest Authority’”

David Ben-Gurion at the Va’ad ha-Poel ha-Tzioni conference, Tel Aviv, April 6, 1948

The Situation

During these last four months, since the attack was launched against us on November 30, 1947, more than 900 Jews have been killed; the Jews of the Old City [of Jerusalem] have been besieged for several months; the whole of Hebrew Jerusalem has been cut off, at least to some degree, for this entire time. It was completely cut off for ten days, with the danger of famine hovering over it. And the danger has not yet passed.

Some of our agricultural settlements—in the Galilee, in Samaria, in the Jordan Valley, in Judea, in the Negev—have been attacked, sometimes fiercely, by hundreds and sometimes by thousands of militiamen. And in the three cities—Haifa, Jaffa-Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem—the provocations haven’t stopped for even a single night. Thousands of armed foreign Arabs, many of whom are officers and men from the armies of neighboring countries, have invaded the country. Their numbers are growing. They come mainly from Syria, Iraq, and from across the Jordan, and a few from Egypt. And they come equipped—some of them, anyways—armed with weapons that had been sent to their countries by the English government.

Meanwhile, many, if not most, of the Arabs in this country, both city and village dwellers, have their own weapons. And he who doesn’t yet have one is making efforts to buy one at exorbitant prices: 100–120 Palestine pounds for a rifle which, as the British government itself has admitted, was brought into this country by soldiers of the Arab Legion. The Legion might seem to be the Transjordanian army, but actually it is controlled by the British empire. And it is better equipped and trained than any other Arab army.

The British Mandate government is hostile to us. Even as its authority crumbles and its departure nears, the British government still tries, by direct and indirect means, to shackle the Yishuv and to prevent its efforts to defend itself. Contrary to the United Nations decision, the British Mandate government refused to hand over the Tel Aviv port on February 1. Although its police and army left the area of Tel Aviv, British warships still patrol the waters of Tel Aviv day and night. In effect, the British government is imposing a naval blockade specifically on the Jews. For the land borders of the country—in the east, north, and south—are open to Arabs, both militiamen and organized armies.

It is true that the British conduct weapon searches on both Jews and Arabs, and, once in a while, they confiscate weapons from both Jews and Arabs. Sometimes the British assist Jewish forces in Jewish communities and sometimes they assist Arab forces in Arab communities. But the British authority distributes weapons exclusively to Arabs, in both cities and villages. The British Mandate authority’s firm security policy is to shackle the Yishuv as it attempts to defend itself while giving every incentive to local and foreign Arabs to attack us.

In addition to all this, we are confronting a void in the provision of state services, a void which has begun long before May 15, 1948. There is no effective authority in the country. Social services are crumbling and being destroyed. The tohu va-vohu [formlessness and chaos] expands, and will culminate on May 15, the day the Mandate authority is officially abolished.

Then, the country will be open to the full onslaught of enemy forces. The reserve forces of the enemy are virtually unlimited. The ratio between the Jews of the Land of Israel and the Arabs in the Land of Israel and in neighboring countries—excluding those of North Africa—is about 1:45. And the Arabs have sovereignty and political recognition. Six Arab states are in the United Nations, and a seventh, Transjordan, is the ally of England. And a great deal of British matériel has been transferred to the Arab Legion.

Meanwhile, the besieged Jewish people still have no political sovereignty, no governing authority, no international recognition. It does not exist at all as a sovereign political entity. And it cannot buy weapons—since weapons are only sold to recognized states. And the Arabs can legally and openly buy weapons anywhere.

Against the Jewish people, who lack a state, there are seven independent Arab states: Lebanon, Syria, Transjordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen. They have trained armies, more or less. Some of them have an air force; Egypt also has a navy.

This is the situation in its essence. And this situation puts fateful questions before us, questions which haven’t faced us in hundreds of years—in fact, in over 1,800 years.

We Have No Choice

The question is not whether we defend ourselves or surrender. We have no such choice. And when I say “we” I am not referring to every Jew in the Land of Israel. An individual Jew, or some isolated group of Jews, could persuade themselves that have such a choice: that could abandon this imperative of self-defense, and surrender.

And I am also not even referring to all Zionists. For some members of the Zionist Organization, it’s enough to donate money. Of course: I do not underestimate the importance of money at so grave a moment. But a mere donor does not have to be killed for Zionism. The question now is beyond money, beyond even the Zionist program. He who gives money to our cause consents to the Zionist aspiration expressed in the [1897 Zionist] Basel Program, but he does not have to give his life for that aspiration.

When I say, “we have no choice,” here is the “we” I refer to: those Jews, both in the Land of Israel and in the Diaspora, who can live only one life: a life of Jewish independence in the homeland.

These Jews, whether they are here now or going to come here soon: they have no choice. They cannot surrender. And they will not surrender. Not to the mufti [of Jerusalem]. Not to the leaders of the Arab Legion and not to the government of Bevin, [the British secretary of state for foreign affairs]. These Jews must do all for self-defense, they must stand for their rights and for the rights of their people for a homeland and independence. And when others try to deprive them of this right by force, they will defend their rights by force, by all force that they have.

To these Jews, this right is both a historical right and an ancestral right, a right bequeathed by generations of pioneers, a right recognized by international authorities, and a right demonstrated by the suffering and tragedy endured by world Jewry over the generations and in our generation. For all these Jews, this right is a question of life and death. They have no choice but to stand in force, and to fight with force, until their rights are established.

The question before us then, is how to fight for victory: a victory will ensure the free existence of our people, the continued development of its work in Palestine, its future as sovereign and political, and its international standing.

A Single Highest Authority for the Sake of Victory

At the last Zionist Actions Committee meeting in Zurich, in August of 1947, I made an unsuccessful attempt. I called on the Zionist movement to recognize that the security situation of the Yishuv is the main, decisive problem that will determine everything—and that security considerations should guide every step of the Zionist movement and the Yishuv, both in domestic and foreign affairs. Apparently, the Zionist movement was not prepared to hear these things then.

Now there is no need to persuade the Zionist movement, and certainly not the Yishuv, that the situation is grave, and the danger is great. Nevertheless, I doubt whether the Zionist movement, and even the Yishuv, has drawn the right conclusions from the situation, and whether they are willing to pledge their lives and their belongings, and plan to do what the situation requires.

We face both the offensive power of the Arabs in the Land of Israel, as well as the enormous potential force of the Arab states, supported politically and militarily by a great power or some combination of great powers. Anyone with open eyes will see that without supreme effort we will not win. And this supreme effort necessitates mastery of the whole life force of the Yishuv: its economy, its manpower, its transportation, its technical and scientific knowledge, its moral power, its newspapers, its communal life, all institutions of the Zionist Organization, and its means and powers of political influence. Without all this, it’s difficult to think that we can meet the challenge.

We will not win by military might alone. In our days no war is waged by the army alone. All the wars of our generation have been waged by whole nations. And our war is not easier than the other wars. Actually, it is more difficult. For this war isn’t only against Jewish military forces, but against the entire Yishuv.

And we here are much less able than in other wars to distinguish between the front and the rear. Every one of us, great and small, man and woman, old and young, whether he wants to be or not, is on the front. And war has been declared against us when we still don’t have the standing of a state nor a recognized government, and we cannot acquire weapons, and when it is not difficult to blockade us by land or sea. Every settlement of ours is on the border and each of us is in effect on the border. Without general mobilization, without full rule over all the powers and means of the Yishuv—we cannot hold out.

With arms alone, even if we had been able to build a bigger army, we will not stand, unless we mobilize the economy as well our spirit and morale. Experienced military men recognize that moral force makes up about two-thirds of military force. But that’s not enough. We also need the third part.

And all of this imposes on us the need to build an entirely new organization in a new framework—both for the Yishuv and the Zionist movement—which is totally adapted to the needs of war.

The main task of this gathering of the Zionist Actions Committee is to reorganize the Yishuv and the Zionist movement. Not according to the Zionist Organization’s constitution, or our thousands of regulations. Not according to how we’ve gotten used to acting over the last 50 years. But rather, [we must organize] exclusively in line with the needs of self-defense. If we don’t do this, we will sin against our mission and will stand in judgment before the eternal court of the Jewish people.

Can We Stand?

A few words must be said about the question that is surely distressing each of you: will we able to defend ourselves? I admit that an affirmative answer should not be taken for granted. Although I’m sure that we can, I wouldn’t try to prove it as we try to prove mathematical theories. I do not have that kind of evidence. I doubt if anyone has any such evidence.

If we were to solicit the opinions of experts in strategy and economics today, who don’t know the spiritual power of the Yishuv and the inner strength of Zionism, I could explain the situation as follows:

“This is the Jewish settlement of 650,000 people, and here is the number of men and women above the age of majority, and here is our agricultural product, and here are industrial assets, and this is its military knowledge and matériel, and these are its financial means. And this is the state of the Zionist movement in America, Australia, South Africa, Poland, and other countries. The Zionists abroad are willing to help the Yishuv but they are constrained by the governments of these countries, and, at any rate, are thousands of miles away. On the other hand, the Arab settlement in this country numbers 1.1 million. And there are 30 million Arabs who aren’t overseas, but live in a contiguous area to our border. And these millions have states and governments and an army and a budget and cannon, airplanes, and ships. And they get arms from England, which supports them financially, politically, and militarily. And they can easily invade the Yishuv.”

If we explained the situation thusly, I am afraid that the experts would answer clearly: no, there is no hope that the Yishuv will stand. And if we had asked these same experts, not today, but four or five months ago, I don’t doubt they would have given a negative answer either.

But here four months have passed, the history of which is pretty well known. We have stood! And the evidence of these four months tells us something significant.

Assessing the Capabilities

When the Arab attack against us began, on November 30, 1947, the Yishuv had no army. We had just local defense forces, which, for 70 years, had defended their settlements when necessary. These forces had a certain national organization, but they were almost completely limited to their specific locales. These were not properly trained soldiers. They didn’t even rise to the level of what HaShomer people had attained 40 years ago. The sole vocation of HaShomer had been the defense of the Yishuv. More recently, our defenders had been people busy with their work lives, just devoting a few hours of free time per week for training. They were thus considered “prepared” to defend their settlements.

Apart from these, there was only one small brigade that numbered a few thousand half-recruited men. The men of this brigade also devoted half their time to work, and only half to military training. But this force was always ready for any call and was not confined to any specific place. I refer, of course, to the Palmach.

There were also the beginnings of one more force that would also be not restricted to a single locale, but this too was composed of volunteers rather than conscripted. These men received some military training, and not only for the defense of their locales. But these men were busy in the factories, in the fields, in shops. Only one or two days a month were left for training. In the jargon of the Haganah, they called this organization the Ḥayal Sadeh [field force].

The budget available for security was disappointing. It did not even reach a third of what England spends on the Arab Legion. I won’t be able to disclose anything about our equipment, but everyone can imagine its state given the conditions in which we live in this country.

So it was in this situation that the ongoing attack against us commenced, on November 30, 1947. That attack hasn’t stopped even for a day, in the cities, on the roads, on our agricultural settlements throughout the country. But note! Over these past four months, the enemy has not successfully conquered a single settlement—and we have isolated and sparsely populated and remote settlements, on the borders and in the Negev. The enemy has not destroyed a single settlement. And not even one has been abandoned.

It is true that in in the cities—in Haifa, in Tel Aviv, and in Jerusalem—Jews in a few neighborhoods had to move to apartments further away from the border, as rifle fire, machine guns, and mortar fire continued night after night and sometimes day after day. But not a single neighborhood has been conquered.

Meanwhile, many enemy points have been conquered by our defense forces, including many which are very far from Jewish settlements—in the Galilee, Samaria, Judea, and the Negev. Here is a list of such Arab settlements: Arab-Suqrir, Fallujah, Halsa, Salama, Yazur, Bir-Adas, Ein-Hezb, Khawasa, Blad al-Sheikh, Nuris, Kfar Kana, Shefar’am, Sasa, Hassas, Hasinia, Abu-Shosha, Qastal, Deir-Ayub, and more. Our boys laid a beating on the Arab militias. Many other settlements, far more numerous than the ones I just named, were abandoned by the Arabs out of fear.

A great battle is now being waged in Jerusalem and over Jerusalem. And even if we have achieved momentary success, it is not over. The road to Jerusalem is not secure. The danger to the city has not passed. But the Jewish part of Jerusalem has never been, since its destruction [in 70 CE], as Jewish as it is now. We now have in Jerusalem a large bloc that is very much like Tel Aviv. It is 100-percent Jewish, settled entirely by Jews.

But Jerusalem does not only consist of contiguous blocs. There are also “islands”: Jews in Arab territory and Arabs in Jewish territory. All the Arab islands in Jewish territory have now been abandoned, such as Romema, Kerem a-Sila, Sheikh Bader, Lifta, and others. But no Jewish neighborhood within Arab territory has been abandoned, even as it has been attacked day and night for two months. And it is attacked not only by Arabs. In Haifa, too, a third of the Arab settlement fled. But Jews have not fled from any city.

There are cases where a lone Jew flees the country. But the Yishuv as a whole—not only in agricultural settlements but also in the cities—still stands. Now, Arabs are evacuating many villages in the area between Tel Aviv and Zichron Yaakov. This may be due to pressure put on them by Arab militia leaders, out of strategic planning: remove the women and children and put in fighting militias. But it may be done out of fear. Whatever the reason, many of these Arab villages will probably not be left desolate. Jewish boys will enter them, as they have already entered several villages.

It should be remembered that the Arabs not only have a massive numerical advantage, but also others, first and foremost, an advantage in matériel. Most Arabs in this country have weapons. Outside of farms and moshavs, Jews have almost no private weapons. Another important advantage for the Arabs is initiative. Since they have been the attackers, it’s been up to them to choose which settlement they attack. This is a major advantage. And finally, on their side stands the British government, as well as the Arab states. And yet, we have stood stoutly. And the Arabs have failed in various places.

What Lies Before Us

These facts justify our hopes for the future even as we must not draw too many far-reaching conclusions. Even if disaster has not occurred over these four months, it does not mean that the danger does not exist. It must be noted that Arab fighting potential has only partially come into the field. It is estimate that there are now six or seven thousand foreign, irregular Arab fighters in the land—but this number could rise over time to tens of thousands or even more. And there is also a regular army.

In a short period of time, there will be complete tohu va-vohu throughout the land. The British government, as long as it is in the country, has a certain duty and acts according to a certain constitutional standard. When the government leaves and hands over authority to the army, the army will rule without any law, responsibility, or obligation. The English parliament enacted a law that the British forces that remain in this country after May 15 can do whatever they please. (These forces are supposed to remain only until August 1, 1948. But I am not prepared to guarantee that the departure will not be postponed for another year, two years, or five years). Parliament’s only caveat was that the army acts “in good faith,” but the army itself will decide what constitutes “good faith.”

There was a dispute between the United Nations Executive Committee and British representatives at the United Nations over the handing over a port to Jews after February 1. The British representatives argued that they could not turn it over because it was not possible to create “divided government.” So long as they are in the country, they must exercise total control.

Thus, anyone who thinks that that the port of Tel Aviv will certainly be liberated after May 15 is wrong. The British navy will be the ruler of the waters of Palestine. In the house I live in, by the sea, I see a British destroyer constantly patrolling between Tel Aviv and Jaffa.

And not only at sea. There is also a British army left in the country, which has no official responsibility now other than its own evacuation. But, of course, it may look to its “security.” And for security purposes it may close off the Tel Aviv port to prevent the bringing of weapons to Jews—since weapons held by Jews could endanger the army. Using similar logic, it might even be able to occupy Tel Aviv, if it deems it necessary for the “security of the army.” And there will be no law to prevent this.

It is also to be expected that the Arabs’ freedom of action will increase after May 15 while it is not certain that our freedom of action to arm and defend ourselves will increase. This is why I say: how we have defended ourselves these last four months is encouraging as well as a source of pride. The Jewish nation and the Yishuv are entitled to be proud of the Jewish defender. But we must not conclude from this that they will avoid all harm, and that there is no cause for concern.

Summarizing these four months of war, I note successes and dangers. We did not abandon any point we held. And no Jewish settlement has been conquered. Our power has increased, and not just quantitively. I will not go into details here, and I don’t want you to overinterpret this. But our fighting power is now greater than when we entered the campaign. And there is a chance, though not a certainty—there is no certainty in either a political or a military campaign—that this power will increase progressively.

The increase in our quantitative power has some objective limits: the size of the Yishuv, and the ability of the Jewish Diaspora to send us more manpower. But manpower is just one of factor. Equally important are equipment, financial means, moral and intellectual resilience. In these we will win.

I believe in victory, and I certainly disagree with the “experts.” And I do so because of one assumption: that the English army, or anything like the English army, will not fight us. Certainly, it will not do more than it is doing now. It will weigh us down, limit us, bind us. But it will not actually fight us.

Based on this assumption, I dare to disagree with the assessments of the “experts.” Because it is not only quantity that determines the outcome. And, under certain conditions, quantity is not among the decisive factors, though it cannot be underestimated. We must know that in terms of numbers we are weak. Our main strength lies in qualitative factors. And therefore a condition of our victory will be the full mobilization of these advantages.

What We Must Do to Prevail

In order to stand and prevail in this great battle, five things are needed.

- To mobilize all our manpower, both as fighters and economically, in the most rational way possible and to the full extent, out of one single consideration: security.

- To prepare, manufacture, and obtain the equipment we need, including land, sea, and air vehicles, according to plans that have already been made and are being made.

- To regulate the economy, industry, agriculture, trade, exports and imports, distribution of funds and raw materials according to the state of emergency. The goal must be the maintenance of a military force that will increase in number and for the maintenance of a Jewish economy, under war conditions, that does not collapse.

- To establish a single, highest central authority for the Yishuv. That authority will oversee manpower and the army as well as the economy—industrial, agricultural, and financial work—as well as all other state services of the Yishuv. And this single supreme authority will receive full and loyal support from the Zionist movement and the Jewish people in the Diaspora.

- Not to be satisfied anymore with mere defensive tactics, but to attack, at the right time, across the entire front—and not only in the territory allotted for the Jewish state, and not only in the territory of Eretz-Yisrael—but rather to crush the enemy force wherever we find it.

Of these five things, only the second thing, the preparation and production of equipment, does not depend entirely on us alone. But the other things depend solely on us. The unique task of this conference of the Zionist Actions Committee is on the fourth point: obtaining the authority to establish a single and supreme central authority for the Yishuv. Without this authority, it will be impossible to stand in the battle.

The Single Highest Authority

The concentration of security matters in one central authority is the essential task of this conference of the Zionist Actions Committee. The Jewish Agency cannot hand over authority to any new body without explicit power of attorney from the Zionist Actions Committee. But without this new, uniform, central authority, no security can be maintained.

After much debate and external pressure—from the Executive Committee of the United Nations—and from concerns about the vacuum created by the abolition of the British Mandate, the leadership here has come to the realization that two new institutions needed to be established. A provisional governing council consisting of 36 or 37 members and a provisional executive, consisting of thirteen members.

Our representatives at the United Nations stood their ground, realizing that we should not miss the moment to set up governmental bodies for the Jewish state in a timely manner, and that we should make a proposal available to the UN regarding their composition in a timely manner. But even regardless of the procedures of the United Nations, we could have concluded—by examining our security situation—that such bodies were necessary.

Right now, we have a jumble of different bodies dealing with security. So many memories [we all have of these]! If I had come here to write history, I would heap praise on the directors of the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem, the directors of the Va’ad Le’umi [National Council], as well as those bodies called the “National Headquarters” and the “Security Committee.” All deserve encomia for what they did for the security and settlement of our country. Neither will I forget the work of the mobilization and fundraising committees. Everyone helped and acted for our security.

But this is not a good time to write history. We are now at war. And we have only one concern—victory. And due to this necessity, I concluded that, in place of all these institutions with their many rights, we need one single office that will channel these powers and arrange things in the Yishuv toward the central concern: security.

As such, it does not matter at all whether the necessary majority of UN member states will recognize our government and government council. It does not matter what will be decided by the United Nations, or what its Executive Committee will do. The military campaign that was imposed upon us requires that we have a central government for the Yishuv—and that government must receive the full support of the Zionist movement throughout the world.

There is now not a single affair in the Yishuv that does not have a direct or indirect relationship with security. The management of factories, the division of labor, the transport of vehicles from the Jezreel Valley to Haifa or from the Jezreel Valley to Jerusalem, the labor of workers, the methods of production in farm and factory. Permitting or banning cake for the market. The distribution of food and fuel rations in a free or supervised market. Free exit or closed borders. Freedom of press or restrictions. These are all security matters.

It is imperative that all such matters in the Yishuv be determined and managed by one authority. If there are two authorities: anarchy. If there are three authorities: double and catastrophic anarchy.

We will establish one supreme, decisive, dominant authority for all vital matters of the Yishuv, not only for security matters narrowly understood. The authority must have oversight over all economic, public, and spiritual life. This office must receive full authority from the Yishuv and the Zionist movement.

Until victory comes, this office will be the sole ruler of all our affairs in the country. Without it there can be no security and no successful military campaign.