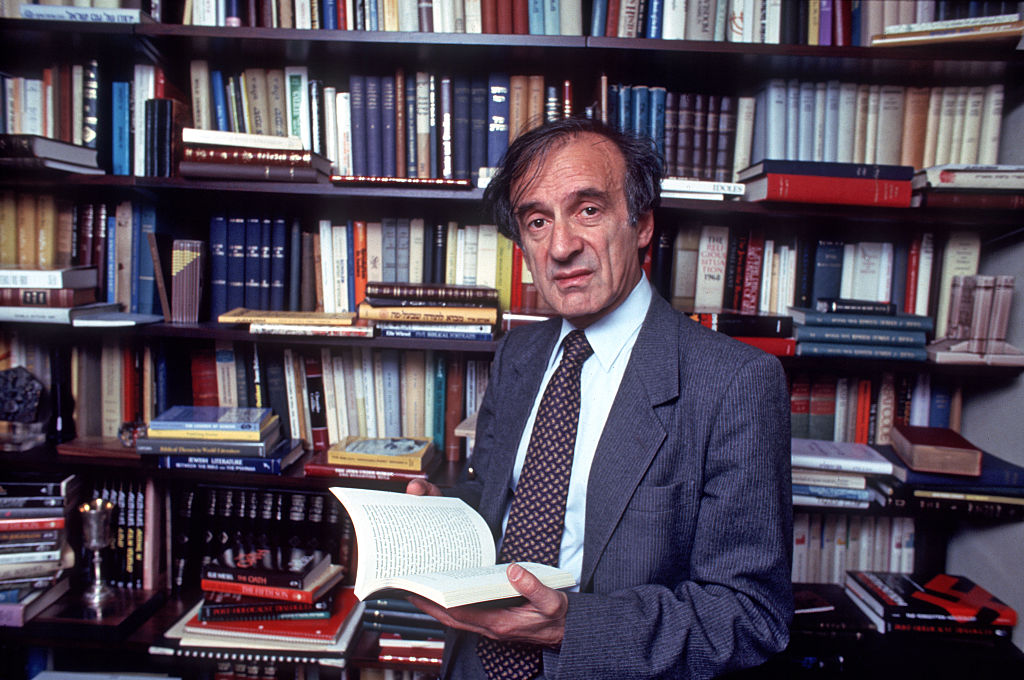

This Week’s Guest: Elisha Wiesel

When Elie Wiesel was fifteen years old, the Nazis murdered his mother and sister and enslaved him and his father in Buchenwald. After the U.S. Army liberated the camp in April 1945, Wiesel went to France, where he studied the humanities and worked as a writer, and then to New York, where he became a professor and an activist for human rights. Wiesel, who died in July 2016, wrote some 60 books, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, and was counselor to presidents, senators, kings, and prime ministers.

Recently, he and his family were honored by the installation of a sculpture of his likeness in the National Cathedral in Washington, DC. The manner of this honoring introduces some particularly vexing Jewish questions, which his son Elisha discussed in a recent Washington Post op-ed. Elie Wiesel was a moral hero, and a particularly Jewish one. His family worried that his memorialization in a church would emphasize the universalist elements of his legacy, and discard particular Jewish elements of his moral persona—including his Jewish observance and his Zionist commitments. Elisha joins Mosaic’s editor Jonathan Silver to think about these questions, his father’s legacy, and more on this week’s podcast.

Musical selections in this podcast are drawn from the Quintet for Clarinet and Strings, op. 31a, composed by Paul Ben-Haim and performed by the ARC Ensemble.

Excerpt (5:03-6:16):

There’s no doubt that when we use phrases like “concentration camps” for things that are not concentrations camps, or that are not the intentional rounding up of prisoners for their political ideology or their nationhood or their race, we run the risk of weakening these terms. When we use the word “genocide” to describe something that is not a genocide, the word “genocide” is a loser there as well. When you use the word “apartheid” to describe Israel, it’s not just that Israel is getting a black eye by the word being used incorrectly, it’s that we’re demeaning the experiences of South African blacks who lived through apartheid, where it meant no shared drinking fountains, no shared restroom facilities. I think language itself is very much under attack.

And you asked about this coming together of universalism and particularism, and the tension between them. My father, I think as much as anyone else, was a master of living right on that edge, of showing how there didn’t have to be a contradiction between the two. For my father, because he was a good Jew, he felt the need to represent Jewish values on the world stage, and the more he interacted on the world stage the more he felt drawn to knowing the solidity of his identity, and how important it was to know where he came from.

More about: Elie Wiesel, Holocaust, Jewish World, Judaism, Zionism