At 5:16 on the evening of November 9, 1965, the lights went out in New York City.

The blackout was the result of a safety-relay tripping in Ontario, which caused a cascade of power failures across the Canadian province, New England, and New York. The outage lasted only 13 hours and if you believe the popular mythology it was one of the most pleasant evenings most New Yorkers had ever experienced. Nine months after the blackout, the New York Times reported seeing a rise in births in the city. The 1968 Doris Day movie about the blackout, Where Were You When the Lights Went Out?, ended with Day’s character giving birth exactly nine months later (with the paternity of the child uncertain).

As it turns out, the story of the blackout baby boom was somewhat oversold. Grumpy statistical analysis suggests that there was no rise in births correlated with the dark night in the city that never sleeps.

But the story of New York City in 1965 is not the last word. In 2014, University of Oregon economist Alfredo Burlando took a more global approach to blackouts and baby booms. What he found actually tracked quite nicely with our popular mythology.

In developing countries where long-term power outages have occurred, there was a very robust baby boom—close to a 20-percent bump. You could see these effects when tracking villages that have been electrified against those not on the power grid, even within the same country.

Burlando’s deepest study is the case of Zanzibar, which underwent a month-long blackout in 2008. But the same effect has been seen in Colombia, where the persistent power outages of 1992 not only created a near-term baby boom, but also resulted in a massive fertility shock, which raised total completed fertility numbers for women in the affected areas by 0.07 children per lifetime.

Demographers have seen similar effects from hurricane warnings—where birth rates tick slightly upward nine months later—but the opposite effect from actual hurricane strikes, which typically suppress birth rates nine months later.

I mention all of this because America is now slowly emerging from something like a four-month blackout. The coronavirus pandemic confined most Americans to their homes or near environs. The idea of a person’s world—the real, physical world they could smell, taste, and touch—shrunk to a scale bordering on the Victorian.

There is no modern precedent for a shock of this magnitude, and it stands to reason that demographers will be watching what happens to birth rates very closely over the next year.

Yet I would be surprised if there is anything like a baby boom beginning in December 2020. In fact, I would guess that in America we will see the opposite.

To explain that prediction, I am going to relate a story about social instability, and economics, and advances in technology. This a story about the pandemic. But underneath all of that, it’s a snapshot of America’s moral confidence at this troubled moment. Altogether, it’s story about the horizons of life itself.

Before the emergence of the novel coronavirus, American fertility had reached one of the lowest ebbs in our nation’s history.

Here’s the 30-second version: The total fertility rate (TFR) is the number of children born to the average woman in her lifetime. When it is 2.1, the population stays stable (absent immigration). Above 2.1, the population grows over time; beneath 2.1, it shrinks.

From the nation’s founding until the 1930s, America’s TFR slowly declined until it sat just below 2.0. Following World War II, America (and rest of the Western world) experienced a remarkable—and quite unexpected—baby boom: fertility rates climbed to about 4.0 for a generation. But beginning in 1960, this boom began to dissipate. America’s TFR has been below the replacement level since about 1970.

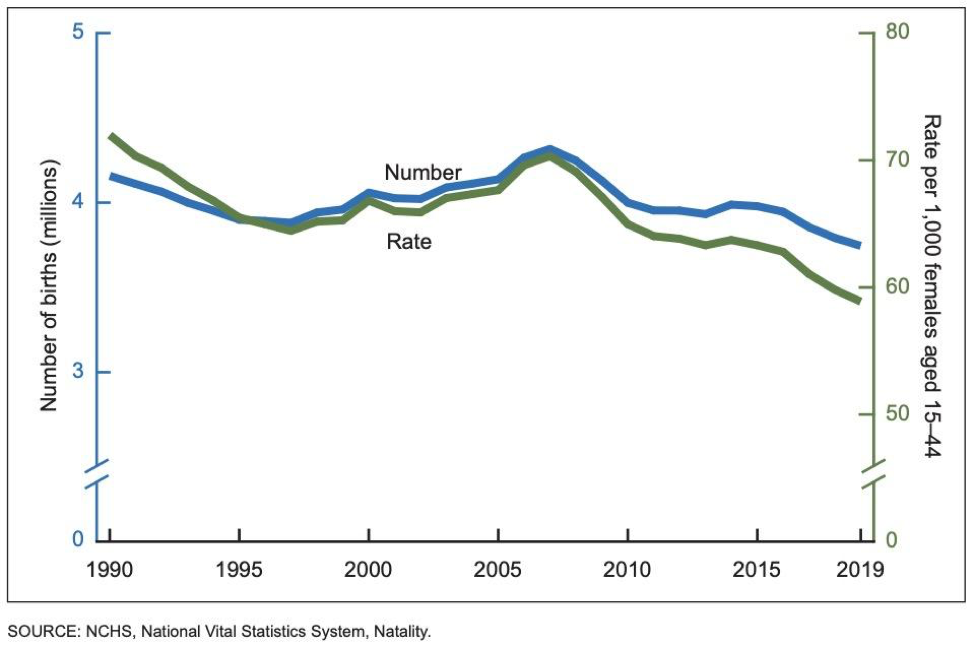

In the late 1980s, the American TFR ticked up to just about replacement level; it stayed at or just about 2.0 from 1990 until the mid-2000s. Since then birth rates have been declining. We now sit at the lowest TFR in American history.

Not only are the fertility and birth rates declining, but so is the raw number of actual births. Every year for the last five years, the number of children born in America has declined by about 1 percent. This has left us with the lowest number of annual births since 1985.

To put that in some perspective, in 1985, the total population of the United States was 240 million. Today our total population is 331 million. Which shows you just how far the actual birth rates—number of births per 1,000 women aged 15-44—have fallen. We have 45 million more women and the same number of babies being born.

What’s happening here is complicated.

Fertility rates are not uniform within populations. There are always subgroups with higher and lower fertility rates than the average. So in order to understand why the average is moving, you have to dig a little deeper into the data.

You can break out fertility patterns by any number of subgroups. For instance, women with only high-school degrees tend to have more children, on average, than women with post-graduate degrees. Women in households making less than $30,000 a year tend to have more children, on average, than women in households making more than $150,000 a year.

Over the last generation, though, these patterns have remained relatively stable.

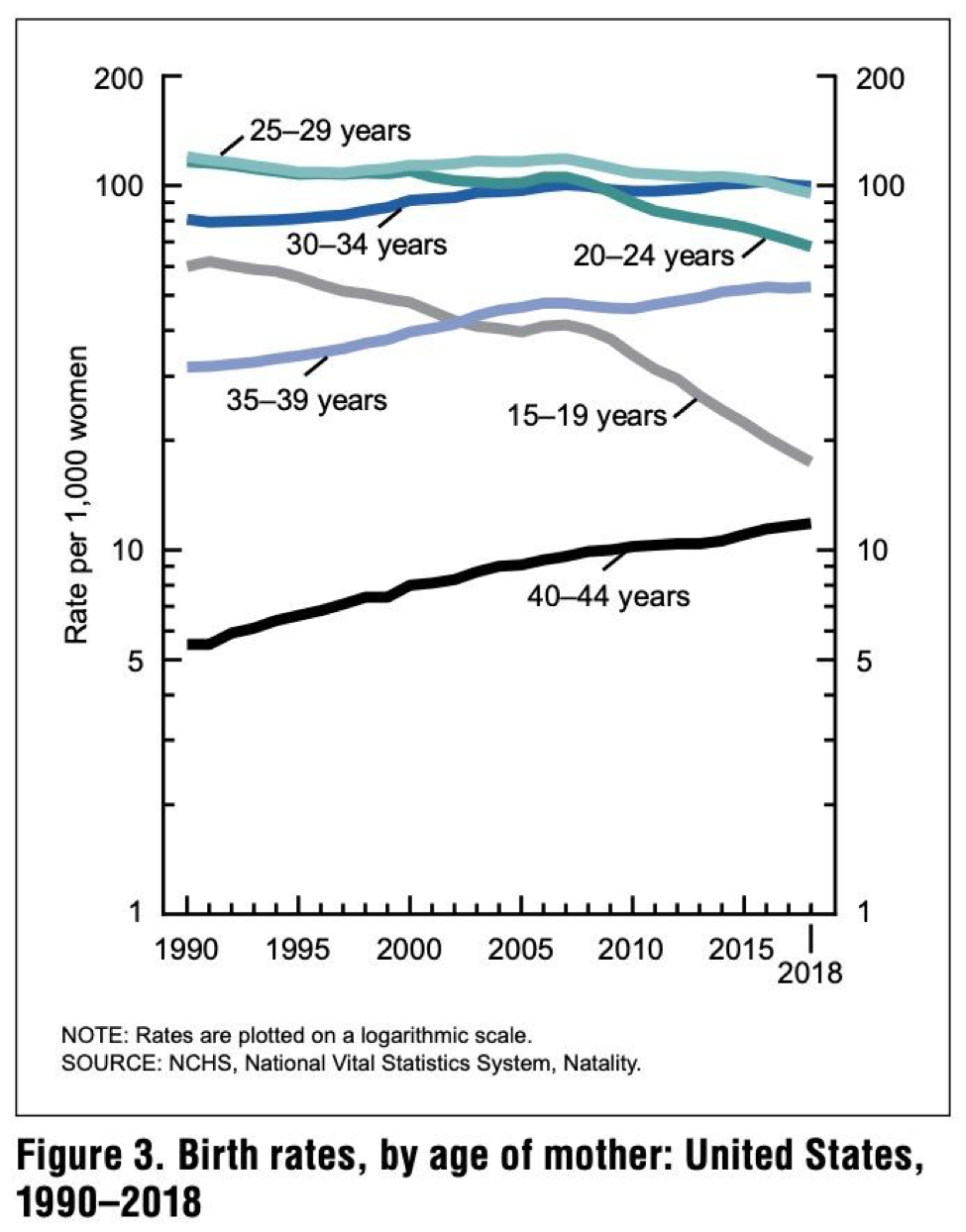

When we zoom in a little closer and look at the birth rate by age of the mother, we see that one of the drivers of our declining numbers is that the birth rate among teens (girls aged 15 to 19) sank dramatically over the last 30 years. At the same time, the birth rate among women over 35 rose.

Race is another driver. There are distinct patterns of fertility in America for black women, non-Hispanic white women, and Hispanic women. Over the last five years all three groups have seen declines in fertility. But the biggest of these declines has come from Hispanic women.

One of the big stories of the last 40 years in American demographics is that our country had a large influx of immigrants from Mexico, Central America, and South America. These immigrants arrived with higher fertility rates than our native population. Yet their fertility patterns collapsed quickly, moving them, within a generation, much closer to the American mean.

This development surprised many observers on both the right and the left. On the right, nativist elements had worried about having the country “overrun” by the descendants of Hispanic immigrants. They imagined that the Hispanic fertility would remain double that of the native-born in perpetuity. Meanwhile, some on the left imagined that high Hispanic fertility would reshape American politics in a permanently Democratic direction.

As it turns out, both sides have been disappointed by the fact that after a generation of living in America, the children of Hispanic immigrants tend to have fertility patterns closer to the national average.

So that’s the 30,000-foot view of American fertility. Our total fertility rate today is 1.77. It has been declining steadily for thirteen years and somewhat dramatically for the last five.

Not great.

But the picture might be even worse than it appears. Over the last ten years, Americans have witnessed a great economic expansion, with a long, strong recovery following the Great Recession of 2008. During the normal course of events, demographers expect fertility rates to rise during economic good times. Ours declined.

Seeing this remarkable fertility decline accompany an economic expansion suggests that there are larger forces at play. When you add in a pandemic—which has no modern analogue—the future begins to look even more grim.

Let’s start with the pandemic.

Two economists at Brookings predict that the COVID-19 crisis will depress births in the United States to a sizable degree—they expect somewhere between 300,000 to 500,000 fewer births over the next year. Last year there were 3.7 million births, so even at the low end, we’re talking about an 8 percent decline.

The Brookings report isn’t the last word on demographics, of course. Anything can happen. No one predicted the Baby Boom which began in 1946 and no one predicted it would collapse as it did a generation later.

But the Brookings projection is based on basic economics, and fertility’s correlation to unemployment. Steel yourself for the report’s summary of academic literature that, together, amount to the most depressing view of romantic life since the invention of the pre-nup:

Black, Kolesnikova, Sanders, and Taylor (2013) find that marital births in coal-producing areas tracked earnings changes associated with the coal boom and bust during the 1970s and 1980s. Kearney and Wilson (2018) find that the higher incomes that came about from fracking led to increases in both marital and non-marital births in affected counties. Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2019) show that places that experienced a reduction in employment and earnings—resulting from increased import competition from China—consequently had lower birth rates. Increases in housing wealth also lead to increases in fertility; Dettling and Kearney (2014) and Lovenheim and Mumford (2013) show that increases in house prices lead to increases in births among existing home owners, consistent with a positive wealth or home-equity effect, while Dettling and Kearney (2014) further show that increases in house prices lead to reductions in births among renters, consistent with a negative price effect.

Remember Zanzibar and Columbia, and the observation that fertility increases in developing countries during prolonged power outages? The key difference between those events and America’s stay-at-home situation of 2020 is the scale of the attendant economic destruction.

If this dynamic holds, the pandemic won’t change the direction of America’s demographic trends. It will accelerate them.

Which brings us to the deeper question: why are people having fewer babies in the first place? This enigma has been the central focus of demographics for 40 years.

There are a raft of theories and explanations, ranging from the logistical (increased educational attainment and access to contraceptives) to the economic (unemployment rates) to the grand (the theory of the Second Demographic Transition, which posits that as humanity becomes more liberal and life centers around the self, people everywhere will naturally have fewer children).

One of the most underappreciated correlations to demographic collapse, however, is religiosity. While adherence to a given religion does not correlate strongly with fertility outcomes, attendance of religious services does. The more often you go to church, synagogue, or mosque, the more children you are likely to have. By quite a lot. A woman who attends services weekly will have almost twice the number of children, over her lifetime, as a women who never attends services.

The decline of institutional religion in America is well documented at this point. The percentage of Americans who belong to mainline Christian denominations has fallen precipitously over the last two generations and the percentage of “nones”—that is, people who have no religious affiliation at all—has grown to a size previously unimaginable. Fully 17 percent of the country now identifies itself as being of no religious persuasion. (This does not include agnostics and atheists, who together total 4 percent of the population.)

To give you a sense of scale, America’s “nones” are now seven times the size of America’s Jewish population.

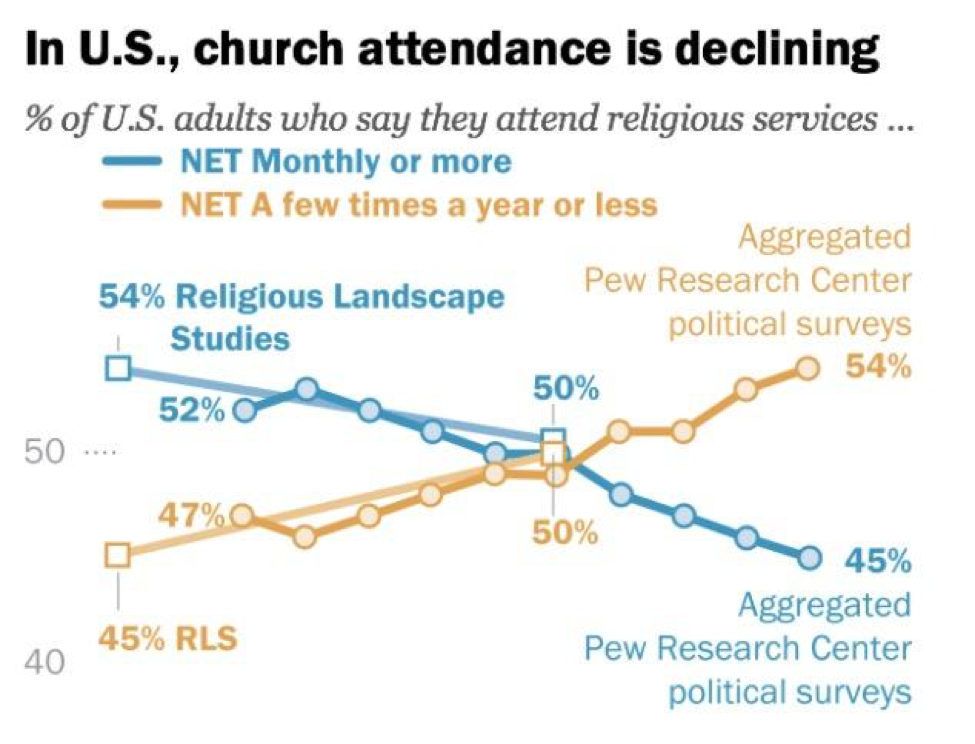

And with the rise of the nones has come a dramatic drop in religious participation, even amongst those who still identify as some sort of believer. In 2007, 54 percent of Americans said they attended religious services once a month or more; 45 percent said they went to services a few times a year or less.

But those lines have been moving in opposite directions: in 2015, for the first time in our nation’s history, we had more people who went to religious services at most once or twice a year than went once a month. And the gap between these groups has grown.

One of the markers we should watch for over the next couple years is whether or not the pandemic accelerates this trend, too.

One imagines that the people who, in pre-pandemic times, attended services every week will come back. One could even imagine that, with so many millions of Americans personally touched by the pandemic, and the random death it visited upon so many people we know—the precipitous passing of a family member, a friend, a coworker, a high-school classmate—the growing human need for spiritual consolation could well bring more Americans into churches, synagogues, and mosques.

But at the same time, it’s not hard to suspect that with houses of worship put into cryosleep for six months, some of the people who were once-a-month attendees will only come once or twice a year. And some of the once-or-twice-a-year folks will fall away completely.

Economic cycles come and go. But the collapse of organized religion tends not to come back without a Great Awakening. And while the current surge of morally charged social-justice energy does share aspects of past Awakenings, it is not an expression of Christian revival, and it hasn’t been shaped by traditional religious forms. There is no evidence that the deeply felt pieties of the moment are connected to a larger understanding of time in which the present generation sees itself under Providence, obliged to ancestors or responsible for descendants. In our moral life, that chain has become unlinked. That is the story beneath the demographers’ reports. We may hope for a religious rebound, but those don’t happen every day.

More about: American Religion, Children, Demographics, Politics & Current Affairs