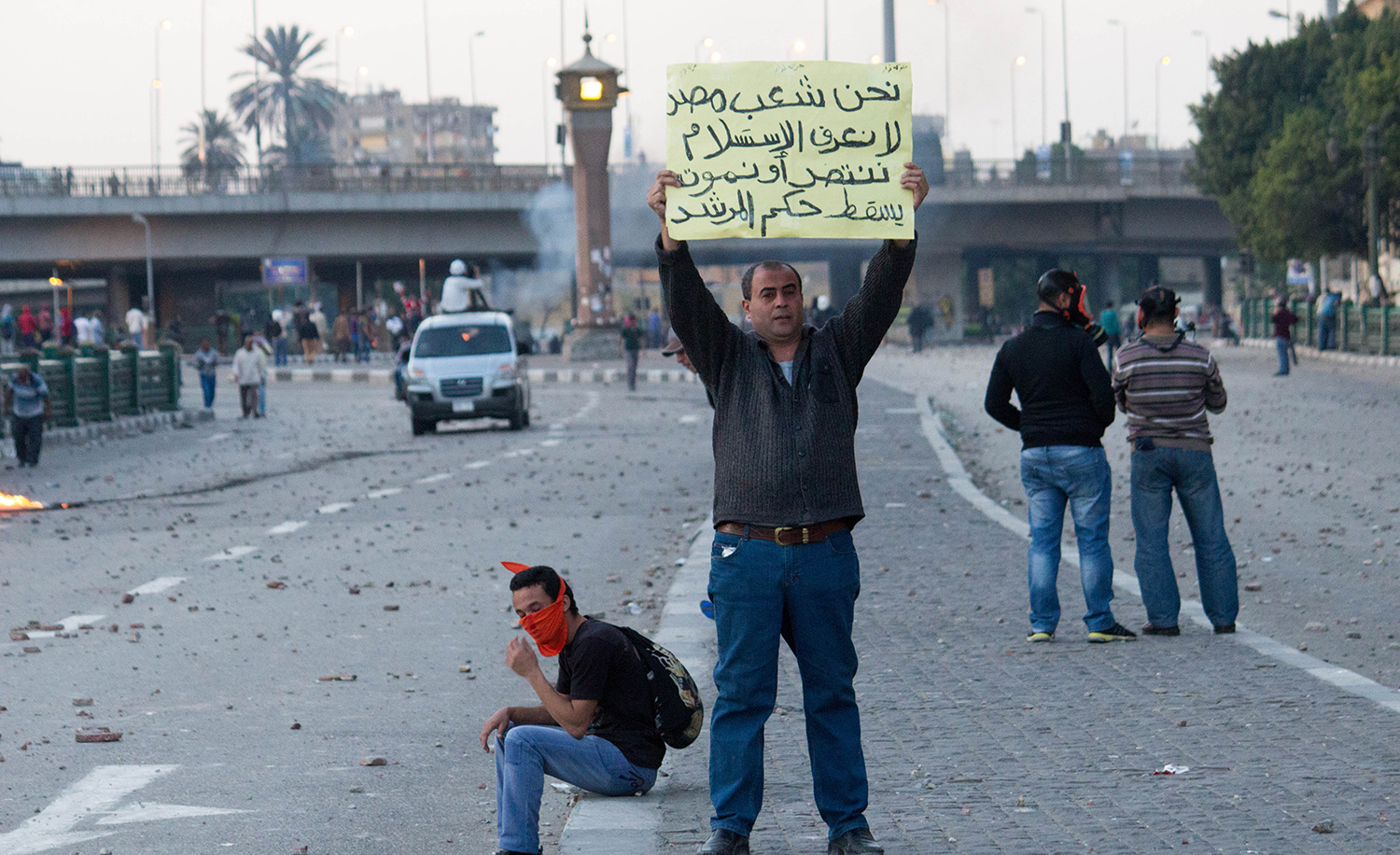

An anti-Muslim Brotherhood protester on April 19, 2013 at clashes near Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo between supporters of the regime of then-president Mohammad Morsi and those in opposition. Getty.

“In 2021,” wrote Marc Lynch, the American political scientist who gave the Arab Spring its name, “there may be few beliefs more universally shared than that the Arab uprisings failed.” His statement sums up the conventional wisdom of observers in the West. And as someone who was not only present in Egypt during the uprising, but was among the throngs of young people in Cairo’s Tahrir square demanding change, I can hardly say that I look back on those days with anything but disappointment. Nor do the stories of other Arab lands caught up in the wave of revolutions invite more optimism. But simply to see the Arab Spring as having given way to an “Arab Winter” is to miss something crucial about what has happened to the Middle East over the past ten years.

The conventional story of the Arab Spring’s failure goes something like this: in 2010 and 2011, people across the Middle East took to the streets en masse, standing up to their despotic and corrupt rulers after decades of submission. Suddenly, there was hope for democracy, or at least some less authoritarian form of government. In most places, however, the protest movements either were smothered in their cradles or led to bloody civil wars. But most tragic of all is the case of Egypt, which held the first true democratic election in its history, only to see the winner removed by a military coup, and then replaced by an even more brutal version of the status quo ante. Hope for Arab democracy has been quashed, and the prospects for political reform in the Middle East are worse than ever.

While none of this is, strictly speaking, false, it is misleading, and what has ossified into the conventional history of this last decade ignores some of the good that has come out of the Arab Spring. These benefits are hardly what anyone in the West or in the Middle East hoped for, but neither are they to be dismissed. “Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made,” Immanuel Kant once wrote. Here, I’ll focus on the case of Egypt, which I experienced firsthand. Despite the many real disappointments, it’s my contention that the events of the past decade have had some positive outcomes for that country, and for the rest of region as well.

This story begins in December 2010, when Tunisians started taking to the streets to protest decades of government corruption and repression, and the dire socioeconomic situation that resulted. The demonstrations succeeded in forcing Zein al-Abedin Bin Ali, serving in his 23rd year as president, to resign from his post and flee to Saudi Arabia. This spark ignited mass protests across the region. But the place on which all eyes were fixed was Egypt, the largest Arab country, home to a third of the world’s Arabic-speakers. After having been ruled for 30 years by the semi-authoritarian president Hosni Mubarak, Egyptians flooded the streets in an attempt to replicate the success of their Tunisian brethren. Following multiple failed efforts by Mubarak to appease the masses with promises of reform, he eventually conceded and resigned—a mere eighteen days after the demonstrations started.

The triumph of the Egyptians, in the eyes of both Westerners and Middle Easterners, was the triumph of man’s liberty against tyranny. Their success also unleashed hopes and speculations inside and outside of the region. Lynch, who had first written of an “Arab Spring” before Ben Ali resigned, was vindicated. What started as spontaneous protests seemed to be nourishing seeds of Arab democracy. From Egypt, all eyes now turned to Libya, Syria, Bahrain, and Yemen as demonstrators took to the streets with their demands. But soon the good tide started to turn. As early as January 2011—one month after Tunisians forced their president from power—anti-government leaders began calling to take up arms against the Ghaddafi regime in Libya. In Syria, the demonstrations dragged on, escalating in intensity without achieving political results.

In Bahrain, the situation quickly acquired a sectarian dimension, setting the Shiite majority against the autocratic Sunni ruling family—stoking the hopes of Tehran and the fears of Riyadh. The situation got even more alarming when Shiite Muslims from Saudi Arabia’s Eastern province started protesting. The Gulf countries decided they were having none of it and the Gulf Cooperation Council’s forces moved into Bahrain to crush the demonstrations swiftly and ruthlessly. In Yemen, a retreat to tribal loyalties and even to a renewal of the brutal civil wars that have plagued the country in the recent decades soon seemed more likely than the flowering of democracy. By mid-2011, it didn’t look so much like authoritarian regimes were falling like dominoes, but instead as if internecine violence was spreading like a plague. Yet throughout all of this, the promise of Egypt remained.

While Libya, Syria, and Yemen were already on the brink of civil war, Egypt remained relatively peaceful. After Mubarak’s departure, Egyptians—after decades when political speech was narrowly constricted—seemed to be arguing about politics everywhere. They debated whether they should have a new constitution or just amend the existing one. They debated whether the Muslim Brotherhood, the Egyptian-born political movement seeking to create an Islamic state, should be allowed to participate in government. They debated whether figures from the old regime should be banished from politics, or allowed to participate in some new, more democratic system. And this sudden eruption of public debate was noisy enough to drown out the gunshots as the military engaged in occasional and limited clashes with groups of young men—mostly soccer hooligans and radical activists. To the Obama administration then occupying the White House, the Egyptian revolution looked as if it could become a peaceful success story of democratic transition; in fact, its success might even legitimize the intervention in neighboring Libya. Alas, disappointment was in store.

After the initial romanticism of the revolution petered out, Egypt had to start confronting knottier problems that don’t lend themselves to slogans and symbolic gestures. Long-term, deep-seated economic and social issues don’t magically dissolve after political victory is achieved. Those were the tough lessons that both young, Westward-looking Egyptian activists and Islamist romantics faced. After the intoxication and euphoria—the feeling of mystical union between the individual and the populace, joined together in a struggle against tyranny—wore off, Egyptians discovered that their differences were not minute, and were often unbridgeable. And here the revolutionaries and their sympathizers met a hard reality: they had called for democracy without realizing that democracy neither presumes nor seeks to bring about the unity of the people. Instead, when functioning properly, it can facilitate compromise among many individuals and groups with diverse interests and desires.

On the eve of the revolution, moreover, Egypt had no viable political parties. Decades of Mubarak’s repressive rule, and that of his predecessors, left an impoverished political culture with many grievances but no meaningful way to address them. By design, the government had eroded the intellectual infrastructure that otherwise might have given rise to movements that could advance specific, competing ideas about politics. Frustration with growing corruption, poverty, lack of freedom, and unemployment had no outlet, while the press rarely criticized the government, and when it did its criticism was mild and supplicatory. Thus no substantive political change could take place absent a revolution—not just against the regime but against the established political culture. The revolution itself famously relied on social media, not newspapers or television, as its primary way of communicating and stirring popular sentiment.

During these events, Wael Ghonim—a twenty-nine-year-old computer engineer working for Google’s Middle Eastern operations—emerged from the shadows as the face of the revolution, not because he was its leader, but because he was an administrator of the Facebook page that scrutinized police brutality and called for demonstrations. Then-President Obama, famously dubbing him “the Google guy,” expressed his wish that Ghonim would succeed Mubarak. But it wasn’t too long before people started to talk about the lack of leadership.

A hopeful twenty-two-year-old at the time, I had a conversation with Ghonim and urged him to find some group of people who could take the reins. He responded with a series of Silicon Valley-style cliches and mumbo-jumbo, which boiled down to an assertion that “leadership would be exclusionary” because the revolution belonged to “all of us.” And so without any organized alternative, it was only natural that the Muslim Brotherhood would step into the vacuum. Nations need leaders, and government needs institutions. The Muslim Brotherhood was the only organized political body in the country prepared to move in to take control.

The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, it is necessary to understand, is the font of all modern Islamist thinking. Since its founding in the 1920s by Hassan al-Bana, the movement has sought to replace secular Muslim republics and monarchies with a new sacred order where society, state, and religion are fused together. Yet neither Bana nor any of his disciples have ever articulated a clear vision of what makes a political system Islamic or how this order can be achieved. The Brotherhood is a political movement without a platform or policies, except perhaps its commitment to the strict regulation of public morality. The group’s sole aim is to seize and maintain power. What happens next is secondary.

As a result, the Muslim Brotherhood’s leaders have been willing to adjust their public statements to fit the political preferences of their potential audience. They have also learned to do two things, and to do them very well: to build an effective, hierarchical, well-disciplined organization able to withstand decades of brutal repression, and to mobilize Islamic symbolism to win popularity.

In short, the Brotherhood holds brand-loyalty paramount, substitutes Islamic symbolism for clear principles, and its ideology is whatever works. Its base of popular support rests not on political conviction but on piety. Paternalistic, authoritarian, anti-Semitic, opportunistic, unprincipled, and power-obsessed, it was and is the perfect representation of all that is wrong with Arab politics—plus an added dose of religious fanaticism.

The Brotherhood’s seemingly endless malleability allows it to maintain an extensive network of members and supporters without the risk of the ideological schisms that plague so many revolutionary movements. Combined with an impressive organizational structure, a simple message, and its ability to project an image of piety to a deeply religious population, this flexibility has made it possible for the group to give rise to offshoots in Gaza, Jordan, Turkey, Kuwait, and even on American college campuses.

In Gaza and Turkey, the group’s local branches—Hamas and Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP, respectively—have embraced democracy as a means to power, and then discarded it after it served its purpose. Their example shows that an Islamic political order is inherently authoritarian and paternalistic. But democracy can only work if participants are sufficiently dedicated to its principles as to accept conflict and loss. Those who believe in democracy only when they win elections can’t create a democracy. But such deep conviction remains largely absent in Arab societies.

Given the Muslim Brotherhood’s almost principled commitment to standing behind no principles, its behavior during the Arab Spring was hardly surprising. Its representatives reached out to everyone and promised everything. They successfully forged alliances with other Islamist forces in the country eager to raise the banner of shariah and to put women behind veil, while assuring the Coptic minority equal rights. They assured the Egyptian military it would maintain its Mubarak-era privileges—the details of their secret meetings with high-ranking officers remain unknown—but also promised reformers that they would demilitarize political life. The Brotherhood also held talks with the Americans, and apparently gained some sympathy from the Obama administration.

An example of the Brotherhood’s incredible capacity for duplicity: during the anti-American protests of September 2012, the organization’s official Twitter account condemned an American YouTube video that insulted the prophet Mohammad, calling on believers to defend his honor, while in English tweeting sympathetic messages to the staff of the American embassy, which had been attacked by protestors doing just that. (The embassy’s Twitter account politely thanked the Brotherhood while mentioning that the diplomatic staff also knows Arabic.)

This willingness to talk out of both sides of its mouth and ideological flexibility, combined with an organizational discipline and a knack for appealing to the religious sentiments of a devout population—especially at a time when the rest of the opposition was leaderless and disorganized—turned the Muslim Brotherhood into an unstoppable political force. For most Egyptians, it was a movement of pious people who opposed Mubarak and offered helpful social services—three powerful strikes in its favor. It could thus easily mobilize wide support for its presidential candidate, bringing the century-long saga of the Egyptian Brotherhood to a dramatic climax. In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine any situation where Mohammad Morsi didn’t win the presidency.

Young and naïve though I was at the time, this outcome was obvious to me, and I didn’t wait for the elections. I left for the United States in April 2012. Voting took place on May 23 and 24, 2012, with a run-off election the next month. Morsi took office on June 30.

After acquiring power, Morsi and his cronies couldn’t figure out how Islamic sloganeering could translate into competent governance. Morsi’s rule didn’t bring reduced corruption, higher incomes, slower inflation, proper treatment of sewage, or better garbage collection. But these were outcomes his pious voters desired. By mid-2013, it became clear that the Brotherhood couldn’t deliver on its promises of economic recovery, and Egyptians started to fume. More importantly, it became obvious around that time that the Muslim Brotherhood had no intention of fostering a “nascent democracy;” on the contrary, the Brotherhood made it plain that it wished to co-opt the repressive tools left behind by the former regime. Many began to see Morsi as a halal version of Mubarak—a corrupt tyrant with a beard had replaced a clean-shaven one. Poverty and unemployment continued to rise; the economy continued to deteriorate; arbitrary arrests, torture, and police brutality persisted.

The Brotherhood had just pulled off a massive power grab. In the 2012 presidential elections, it had been able to secure the presidency through a wide political coalition of all the population segments that wished to oppose the candidacy of then-Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq—a lifelong friend of Mubarak, as well as a relative by marriage—who embodied the regime’s political elite. The coalition included shariah hardliners, semi-secularists, quasi-liberals, and many who simply didn’t want to return to the status quo ante. Yet, after the Brotherhood’s victory, it became clear that it had no intention of honoring any of its promises to its coalition partners. Rhetorical compromise had come easily, but power-sharing was out of the question. For Morsi, democracy was a means to establish Islamic control of the government. A year into his presidency, both diehard Salafists—more extreme Islamists who had a clear vision of a regime that imposed shariah law in the style of Saudi Arabia and Islamic State—and Western educated semi-secularists found themselves again emptyhanded.

That was the backdrop of the 2013 military coup that ousted Morsi: a struggling economy, the Brotherhood’s unwillingness to share power, a return to repressive rule, an alienated political class, and a rising fear of rapid Brotherhoodization of state and society, not to mention the Mubarak-era figures eager to get back in the game. Many Egyptians—both those concerned only with their daily bread and those interested in a democratic transition—were boiling with discontent. The Egyptian military, a ruthless and tenacious institution that has survived all the political upheavals of the past 70 years while maintaining control of the population, took notice.

During the days preceding the coup, anti-government demonstrations grew larger and more frequent, accompanied by long lines at gas stations, power outages, and shortages of basic goods. (There is evidence that members of the military and economic elite, perhaps in coordination with the Gulf states, helped to engineer some of these problems to discredit Morsi.) Meanwhile, the UAE and other anti-Brotherhood regional powers gave financial support to the protest movements. On July 3, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, appeared on television accompanied by the grand imam of al-Azhar (Egypt’s highest Islamic religious authority), the Coptic pope (representing the large Christian minority), Mohamed el-Baradei (the leading liberal figure), and a representative from the Salafist party, and announced Morsi’s ouster. In other words, the same consensus that brought the Brotherhood to power had joined forces with the military to remove it.

But the Brotherhood, having tasted power, wasn’t going to give it up easily. The months following the coup were chaotic, dangerous, and tragic. Over 80 churches were burned to the ground by pro-Brotherhood mobs. In Alexandria, Muslim Brotherhood sympathizers threw counter-protesters from rooftops—a scene, played out on television, reminiscent of the 2006 Hamas-Fatah civil war in Gaza. But the Brotherhood didn’t have a monopoly on brutality: the new government broke up a sit-in at Cairo’s Rab’a Square, killing over 1,000 protesters. New prisons were built, terrorism spiked, and the country went into a state of fearful disquiet. Brotherhood members who could flee to Turkey or Qatar did so. After surviving in opposition to various authoritarian regimes for nearly a century, the original Islamist organization was decisively crushed in the country where it was born. It took Sisi some time and much brutality to get the job done, but he prevailed.

Ruthless and undemocratic though it was, the 2013 coup was by no means a usurpation of democracy. Rather, it was a case of an undemocratic force overthrowing an anti-democratic one. The Muslim Brotherhood had no interest in democracy nor in political pluralism. Despite the claims of its Western sympathizers, Brotherhood-affiliated parties will never become “responsible stakeholders” in a multiparty system. If Egyptian democracy was ever a possibility, that possibility died when Morsi won the election, not when Sisi seized power.

The Egyptian people, in large numbers, do not see Sisi’s assumption of political power as a disaster. Indeed, the lesson that I and my fellow young, Westward-looking idealists learned was that the outpouring of opposition to Mubarak stemmed not so much from a desire for democracy but for better economic and material conditions. At the Tahrir Square protests, the main slogan was “bread, freedom, and social justice.” Two of these three terms are economic, and freedom, for most, didn’t mean American-style liberty but simply what might be called good governance. We wanted competent rulers and administrators who could create the conditions for our families to prosper. In a way, this wasn’t so much a revolution in the sense of an attempt to overthrow the regime, as a popular attempt to replace the current ruler in a system without elections, term limits, or a meaningful parliament. In Britain or Israel, if you don’t like the prime minister, parliament can hold a no-confidence vote. In the U.S., if you don’t like the president, you wait until the election and vote for the candidate from the other party. In Egypt, your only choice is to take to the streets.

For Egyptians, democracy remains an alien and suspect concept. It entails the acceptance of risk and uncertainty, and a willingness to accept results when one’s own side loses. In an unforgiving society where politicians who lose power often lose their lives—and their families, or even ethnic, tribal, or religious communities can suffer a similar fate—democracy seems to come with at a very high price. I believe Egyptians, and many other Arabs, are wise not to want to pay that price. So long as victory means absolute victory and loss means absolute loss no Arab society can, or should, play with democracy.

Once again Egypt demonstrated one of its most remarkable advantages: an exceptional ability to reverse course and abort grand national projects, an ability coveted in an unforgiving neighborhood where mistakes immediately lead to the guillotine of history. Following the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970, Egypt was able to retreat abruptly from Arab nationalism, radical politics, and war with Israel, a pivot that other Arab states knew they could not themselves afford. In the wake of the Arab Spring, Egyptians likewise chose to slam on the breaks and make a U-turn. The Arab Spring proved the conventional wisdom that revolutionary politics amount to playing with fire.

To Egyptian men and women of my generation, the generation of the Arab Spring, talking about the revolution isn’t easy. We are still grappling with a sense of both personal as well as collective failure. The feelings of deep disappointment are hard to overstate. Just like the generations before us that were swept up by radical Arab nationalism and pan-Arabism we discovered that the winds of change had blown only to send the ships of our dreams crashing on the shores of reality.

Many young Egyptians I know came to regret not only helping the Muslim Brotherhood to power, but even the revolution itself. After all, the Sisi regime has proved even more repressive than its predecessor, and hasn’t been much better at putting bread on people’s tables. Many unapologetically say that letting Mubarak’s son, Gamal, succeed him in the presidency might have been more beneficial for the country. In this way, we’re not so different from the Western pundits and professors.

But perhaps this outlook is too pessimistic. Egypt, the most populous Arab country, kept its territorial integrity, state structure, social cohesion, and—despite economic difficulties and cruel political repression—political stability. It is easy to assume that over 100 million Egyptians are nothing but mere victims of the conspiracies of military officers and Arab princes, as the New York Times’s former Cairo correspondent David Kirkpatrick argues in his book Into the Hands of the Soldiers, but perhaps Egyptians made a conscious bargain. Maybe they preferred to struggle with a corrupt and autocratic state over the risk of political instability and Islamist lunacy. Indeed, many Egyptians, including the overwhelming majority of Egyptian Christians, see Egypt as a success story rather than a failure. Those feelings are validated if one looks at neighboring Libya and a not-so-distant Syria.

This is not to defend Sisi’s authoritarianism, but to recognize the practical alternatives that we faced in 2013. It seems to me that Egyptians chose the lesser of two evils. Yes, Sisi surpassed all his predecessors in cruelty and repressiveness. Yet to imagine that the alternative to Sisi was democracy, or even some semblance thereof, is delusional. Egypt is better off with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood out of power. Tens of millions of Egyptian Christians and Muslims would agree.

But while the 2013 coup didn’t undermine a potential Egyptian democracy, it did lasting damage to the idea of democracy in the eyes of Egyptians. If free and fair elections translate into the rule of the Muslim Brotherhood, Egyptians want nothing to do with them. Egyptians once again learned that it is better to focus on their daily bread rather than the shiny Western words that make for big promises and big failures whose costs we ourselves must bear. The images of Muslim Brotherhood members clubbed nearly to death by the same hands that brought them to power only a year earlier will haunt Egypt for decades.

Egypt’s current autocrat seems to have learned a lesson very different from the one we would have wished him to, namely that what Egypt needs is not a healthier political life, but no political life at all. In Sisi’s Egypt, even the narrow margin of opposition that had existed under Mubarak has been completely shut down. The state mostly succeeded in exterminating the Brotherhood. People get arrested over jokes posted on social-media sites. No one dares to make political demands, and the state ensures that those who do so never demand anything else.

Yet the old-new regime’s record is not all bad. The government is pushing a top-down program of religious reform aiming to make the culture less hospitable to Islamism. Economic reforms have yielded some modest success: foreign-currency reserves, which took a deep dive after 2011, seem to be recovering, the currency is slowly appreciating, and, if you speak to Egyptians, there is a general sense that things are slowly getting better. Nobody wishes for political drama any time soon. Will Sisi’s attempt to cleanse Egypt of political aspirations provoke a backlash, much as Mubarak’s efforts did? Will his exterminationist approach towards Islamism prove effective, or will it summon even worse demons? Only time will tell.

Although Islamism remains alive in Egypt, despite Sisi’s efforts to crush it, its popularity has been vastly diminished. Islamism proved to be nothing but a collection of disparate political obsessions and empty symbols, with no vision of how it can fulfill its promises or create something better than the alternatives. All it can do is seize power.

Once one of the most popular movements in the Arab World, the Muslim Brotherhood has lost a great deal of its credibility, and not only in Egypt. As Arab populations are attempting to assess and learn from the failed experiences of the Arab Spring, they are paying more attention to the problems and dangers of Islamism. The Jordanian intellectual Wadah Khanfar put it plainly: “If you sit with any Muslim Brotherhood [member] now, he is trying to find a way out; millions of questions but no answers about the theory of political Islam itself. . . . A hundred years have passed since Hassan al-Banna established this organization. Is it still valid to adopt a concept called political Islam?”

Furthermore, the dystopian rise of Islamic State was a sobering experience for most Arabs. Today, and for the first time in modern Arab history, there is a significant segment of Muslim public opinion that is deeply suspicious of any deployment of religious symbols in public life. Denizens of Egypt and the Arab Gulf states may lack free speech to talk about politics today, but surprisingly enough, they have a lot of free speech to talk about structural problems in mainstream Islam. Thinkers, journalists, and writers are starting to question openly many of the pillars of Arab life, including the public role of religion and the unfailing commitment to the “resistance,” the common euphemism for fighting Israel and America.

For decades Arabs provided complete support to anyone who raised the banner of Islam or resistance against the West and Israel. Palestine had become a sort of parable through which people could voice political grievances. No longer. Recently, the Kuwaiti daily al-Jarida published an op-ed by the Shiite writer Khalil Haider, examining the blanket support for Islamic resistance movements such as Hizballah:

How tragic was it that legalists, activists, and academics in the Arab world never questioned the legitimacy of bypassing and ignoring the laws of the Lebanese state and the undermining of civic freedoms by Hizballah, and did not forcefully and loudly criticize the fact that Hizballah, a Lebanese faction tied to a foreign state [i.e., Iran], is, in fact, a military mightier than the state’s military. Hizballah has military and security capabilities which are not subject to any clear legal oversight and is able to insert the entire country into destructive wars whenever it wishes!

Such sentiments now appear on a near-daily basis in the mainstream Arab press. There is a coalition of rulers, secular thinkers, and middle-class Arabs who want to discredit Islamism. The Abraham Accords should be seen in this context: not as cynical geopolitics but as a means of moving the populations of the Arab Gulf as far away possible from Islamism, and from the anti-Semitism that accompanies it. Even Saudi Arabia, the country responsible for the global spread of an austere form of Islam that makes the Muslim Brotherhood look positively enlightened, is reversing much of its pro-Wahabi policies and providing its population much needed social relief. Taken together, these developments speak to a conscious movement away from Islamism and the paradigm of resistance politics.

We cannot tell whether such a move will succeed or what is the alternative it will bring. The Middle East is likely to remain volatile and unstable for a long time. In Yemen, Syria, and Libya the Arab Spring can’t be said to have come to an end until the civil wars there cease. Iraq and Lebanon, meanwhile, stand on the brink of similar catastrophe. And so far this instability has redounded to the benefit of Iran, which has become the most predatory regional power to appear in the region since the Ottoman empire.

The societies of the Arab world are currently in a state of flux, but no one can tell in what direction they are moving. There are reasons for hope and for caution. The emotional power of Islam can still captivate the hearts of millions. However, in Egypt, Islamism may be so discredited that even Islamic symbolism cannot redeem it. Given the importance of Egypt in Arab and Muslim world history, this embrace of Islamism’s limits is cause for chastened hope.