When it comes to Iran, the Biden administration has replaced its predecessor’s policy of “maximum pressure” with one of “maximum deference”—or so runs the refrain coming from many intelligent observers. This line of reasoning isn’t, strictly speaking, wrong: the Biden White House has indeed sought to reengage Iranian negotiators with softer rhetoric, very different from that of the Trump administration. And it has quietly pulled back certain sanctions while signaling a willingness to make further concessions. But overall Joe Biden’s policies have not deviated substantially from those of the two previous presidents.

The Biden administration has removed several sanctions targeting Iranian officials and entities as a gesture of goodwill, despite the president’s pledge not to do so. But the most important sanctions—those that restrict the government of Iran’s ability to conduct international financial transactions and minimize its oil exports—remain in place. Additionally, the administration, on two different occasions, has conducted a total of four separate strikes against Tehran’s proxies, two more than its predecessor. So despite the lifting of a few sanctions, the Islamic Republic is not feeling much change. And that means that, while President Biden is not exerting maximum pressure on the Islamic Republic, neither was President Trump.

That’s not to say that the pressure that Americans is currently applying is inconsequential. But it is pressure of a certain kind: economic pressure. Indeed, it is fair to say that the Trump administration exerted maximum economic pressure on Iran—doing almost everything short of imposing a blockade, which would constitute an act of war. In trying to use sanctions to force the Islamic Republic to abandon its pursuit of nuclear weapons, President Trump was employing, with far greater intensity, a strategy introduced by the Clinton administration, one pursued haphazardly by every American president since. All of them have failed to bring a permanent end to Iran’s nuclear program.

It is understandable why sanctions have been tried for so long, for, in the hands of the right statesman, economic pressure can be a useful tool. And though they haven’t been entirely successful, the arguments in their favor are not to be dismissed.

First, they have significantly diminished Iran’s finances, and the shortage of cash has hurt its military, particularly its elite paramilitary branch known as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). A 2019-2020 draft budget submitted to Iran’s parliament demonstrates that Tehran’s allocations to armed services have decreased significantly. With fewer resources at its disposal, the IRGC likely had to weigh trade-offs when considering various expenditures. Put bluntly, the less money Iran has, the less damage it can afford to do.

Second, the sanctions have accelerated economic turmoil within Iran. Of course, even absent external pressure, the Islamic Republic’s rampant corruption and its quasi-socialist system render prosperity unachievable, despite the country’s ample natural resources. Nevertheless, by intensifying the pre-existing ruinous economic dynamics, sanctions have contributed to mass unrest and protests. These expressions of frustration could—with external support—threaten the regime’s stability.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, sanctions are palatable to the American public and to the presidents who have sustained them. Voters have little appetite for military engagement in the Middle East; the current administration has made competition with China its foreign-policy priority, and has no interest in distractions.

But appealing as economic pressure is, it also has definite limitations which can be apprehended by stating the two assumptions on which it rests. First, for economic pressure to succeed, sanctions must be able to coerce Tehran into ceasing its quest for nuclear weapons, and, second, sanctions must be sustainable over the long run. And the the truth is that it won’t, and they aren’t.

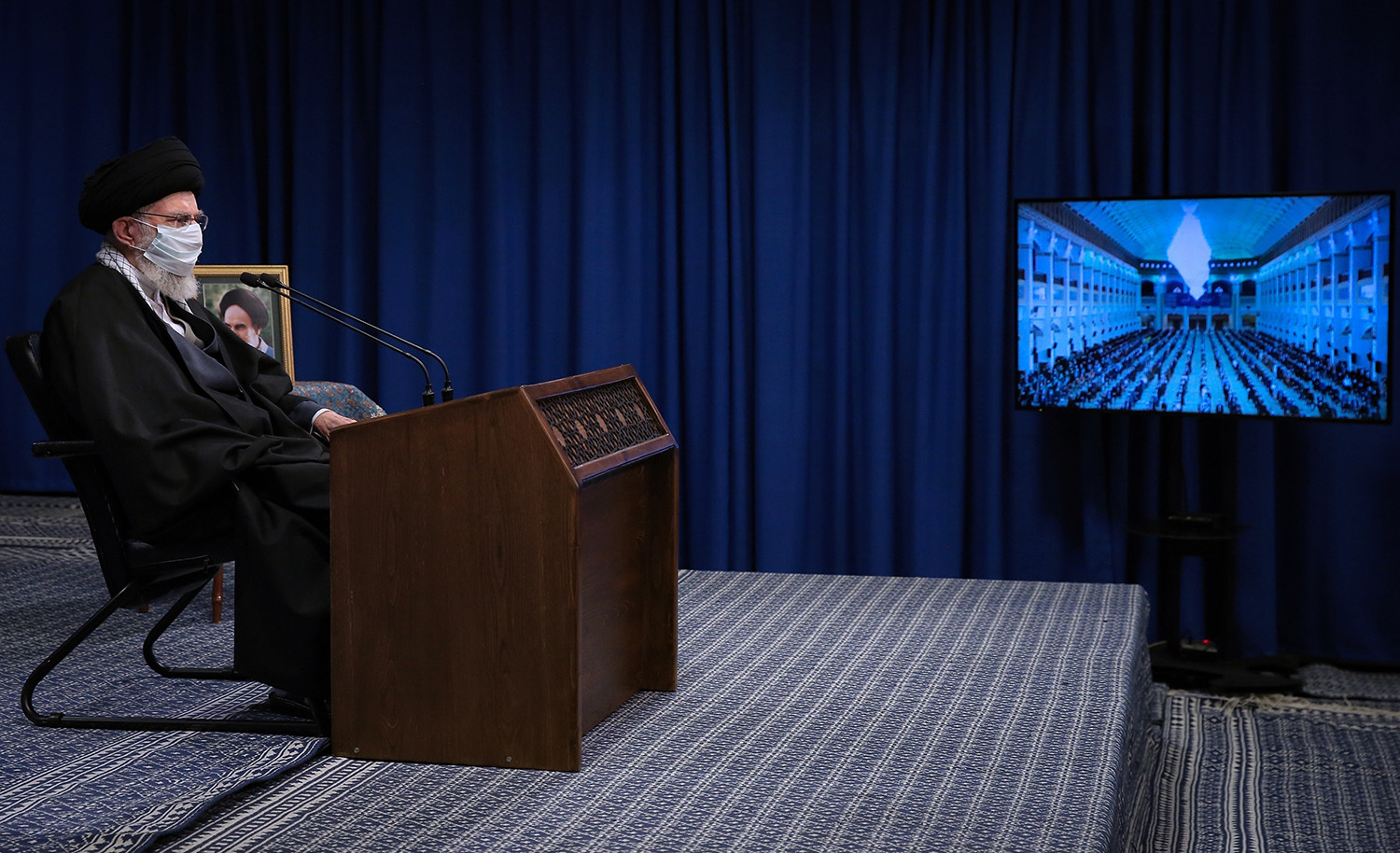

Westerners tend to assume that a country like Iran is eager to improve its economic conditions. But the regime has for years spoken of an autarkic “resistance economy,” an idea the new president, Ebrahim Raisi, has also championed. Although ultimately Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei calls the shots, the president plays a role in implementing policy, and in this regard Raisi differs sharply from his predecessor, Hassan Rouhani. Raisi, guided by “resistance economics,” will strive to render Iran economically self-sufficient and impervious to the influences of foreign trade. To Raisi, and to Khamenei himself, such a policy is worth the inevitable reduction in standards of living.

Moreover, Iran has vast supplies of petroleum and natural gas, which have long driven its economy. Sanctions on Iranian oil, which are the most important part of the economic-pressure campaign, keep it off the market, artificially reducing global supplies. So every time gas prices go up, the cost of preventing Iran from selling its oil seems greater, ultimately making sanctions less sustainable. The sanctions regime has so far been maintained with the reluctant support of Britain, France, Germany, and China, all of which are oil importers who prefer lower prices. At some point these countries will no longer be willing to endure economic pain in pursuit of foreign-policy goals. Furthermore, two of the main destinations for Iranian oil are Japan and South Korea, both of which oppose the sanctions. Given its intensifying contest with China, the United States can’t afford not to take these Asian allies’ economic concerns seriously.

If gas prices continue to rise, American voters too will lose their patience with sanctions. Taken together, these circumstances make maintaining economic pressure on Iran extremely difficult, even unfeasible. Tehran, by contrast, can stubbornly cling to its nuclear program and hope to ride Washington out.

For sanctions to succeed, the regime would have to conclude that their cost is greater than the value of its nuclear program. But this is a calculation it is unlikely to make, given that nuclear weapons are too cheap to produce for sanctions to be a financial obstacle. Policymakers in the West have consistently failed to realize that Iran’s rulers prize ideology over prosperity, and survival above all else. It is this commitment to self-preservation that is at the core of their nuclear ambitions.

The Islamic Republic has learned an important lesson from the experience of two other Muslim states with nuclear ambitions and a penchant for funding terrorism. The first is Pakistan. As many have observed, the United States could have defeated the Taliban relatively easily had it been willing to take the fight against it into Pakistan, and had it exerted sufficient pressure on Islamabad to stop providing the terrorist organization with financial and logistical support. But America is much too invested in Pakistan’s survival and stability to do so. Why? Because Pakistan is a nuclear power, a fact terrifying in itself, but not nearly so terrifying as the prospect of a Pakistani nuke going missing or falling into the hands of al-Qaeda—which could happen if the regime were to collapse. An equally terrifying possibility is if the regime, finding itself on the brink of collapse, were to take a “use it or lose it” attitude toward its nuclear arsenal. This is why Washington has tolerated all kinds of bad behavior from one Pakistani government after another.

On the other side of the spectrum sits—or used to sit—Muammar Ghaddafi, who gave up his nuclear program only for the West to oust his regime a few years later without thinking twice. The choice is quite clear for Iran. If the regime gets nuclear weapons, it can become Pakistan. If it gives them up, it runs the risk of becoming Libya.

Last, there is the risk that sanctions will backfire. There is a tendency in Washington to believe that Iran’s intention for accelerating work on its nuclear programs since 2019 is to use it as a bargaining chip. That might very well be true, but a comparison with Russia helps to explain an alternative possibility. A combination of corruption, low oil prices, and sanctions have terribly hurt the Russian economy, forcing Vladimir Putin to adopt low-cost strategies to substitute for the shortcomings of his conventional military. One of these strategies has been building so-called “theater” nuclear weapons, which are smaller than the usual kind and, in theory, are designed for use in the midst of battle. If economic problems have in fact hurt Iran’s military power, it might very well be seeking to strengthen its negotiating position by increased enrichment of uranium, but it is reasonable to suspect that the regime might also be accelerating its nuclear program as a substitute for its weakening conventional power and that of its regional proxies. In other words, sanctions will lead to limited resources, which might in turn encourage Tehran to build nuclear weapons.

Iran is determined to have these weapons, and sanctions and diplomacy are not going to stop it. At the end of the day, it sees economic pressure as a nuisance rather than a serious threat. Within the Obama administration, there were hopes that, if Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons were delayed long enough, Khamenei might die before it got the bomb, and perhaps be succeeded by someone more willing to compromise. Chances of this happening were slim then and are now altogether nil. After some senior figures publicly expressed sympathy for the 2009 Green Movement protests, the regime purged them from the ranks of the Revolutionary Guard, the clergy, the state apparatus, and the assembly of experts that will select Khamenei’s successor—expelling or murdering any potential reformers. In doing so, it has made more or less impossible the emergence of anything like an Iranian Mikhail Gorbachev. Whoever succeeds Khamenei will no doubt be made in his image. In fact, given the increasing influence of the IRGC on domestic politics, we are likely due to miss Khamenei’s “moderation” after he dies.

If the combination of sanctions and diplomacy endorsed by every president since Bill Clinton are not to work, three options remain. First, preparing for a nuclear Iran and learning to live with it. Second, a military operation that would dismantle Iran’s nuclear program. Third, regime change before Iran acquires nuclear weapons. Let’s take a careful look at the second of these.

Despite assertions by isolationists and appeasers, the military option doesn’t mean invading Iran, but it possibly requires something more involved than the one-off strikes the IDF used to eliminate the Iraqi and Syrian nuclear programs in 1981 and 2007, respectively. The greatest danger of such an attempt is that Tehran would retaliate with conventional attacks, perhaps through its proxies, which might lead to further escalation, which in turn could spiral into all-out war. Especially concerning is the unlikely but real possibility that the Islamic Republic retaliates against America’s Arab partners, or Israel. But recent evidence suggests that the possibility of escalation is low. Iran’s retaliatory strike against American troops in Iraq in response to the killing of Qassem Suleimani was merely an attempt to save face; Tehran effectively gave the U.S. advance warning of the attack, precisely because it feared that American casualties would necessitate an American response it didn’t want to risk. Going to war against a superior military force is a fatal mistake, and Iranian leaders have shown themselves to be calculated risk-takers.

Moreover, war with the United States would leave the regime vulnerable to its restive population, a majority of whom are unwilling to fight for the Islamic Republic’s survival, and a sizable minority of whom might seize the opportunity to collaborate with the Americans or to seek to overthrow the regime. Besides ample evidence of the mullahs’ unpopularity with their subjects, we also know that a significant number of Iranians—some of whom no doubt occupy important government or military positions—have cooperated with the Mossad.

Those who believe that sanctions can convince Iran to give up its nuclear program need to grapple with the fact that economic pressure did not stop North Korea from becoming a nuclear-armed state. Decision-makers within totalitarian regimes like the Islamic Republic have three main incentives, which are not mutually exclusive, but are quite different from those of democratic politicians. First, they are concerned for their personal wealth, which can be reduced by sanctions, but not significantly enough to convince them to deviate from those policies that, they believe, will ensure the survival of the regime that made them rich in the first place. Second, they are ideologically motivated. The sincere believers inside Iran’s clerical class are not as concerned with the material and earthly wellbeing of their subjects as much as they are with getting them into heaven, even if they have to do so by force.

Lastly, and most importantly, Iran’s rulers are motivated by survival—not just the regime’s but their own and that of their families. Calls for the execution of senior leaders are rampant on Farsi social media. To avoid detection, users have adopted “streetlamps” as a codeword, a reference to the lynching of the shah’s security forces from streetlamps after the 1979 revolution. The regime and its decision-makers know that the fall of the Islamic Republic would spell the end of their individual lives, and nuclear weapons seem to be the only way out. No amount of economic pressure is enough to make them crack.

More about: Politics & Current Affairs