At a moment when political passions have turned American politics into a vicious battlefield, Joseph Lieberman stood out as a believer in a different view. Lieberman‘s life and political career were tributes to the famous words once spoken by Abraham Lincoln: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

That is how Joe Lieberman approached politics: there were opponents, who for sure had to be defeated, but there were no enemies. The goal was to win, not to destroy or humiliate. Friendship and partnership were more important than party labels, because politics was about the common good—and was never an excuse for vilifying someone who simply disagreed with you.

In all of this, Lieberman was certainly rowing against the stream of American political life. Partisan and ideological divisions deepened during his political career, which began in Connecticut in 1971. But 40 years as a politician never changed him. The words being used today about his geniality and civility are the right ones. The sickness in our politics never poisoned Joe Lieberman.

There is no doubt that his religion was a key antidote. A believing and practicing Orthodox Jew, Lieberman lived his faith; no political triumph ever seemed to dent his graciousness or his humility. The stories are legion about the steps he took to respect the Sabbath and Jewish holy days while fulfilling his political obligations. I am only one of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, who were talking with Lieberman when he looked at his watch and said “come join me for Kabbalat Shabbat” or “will you be the tenth man?”

Lieberman’s conduct reflected his nature as a human being and his religious beliefs but did not reflect a lack of deep political commitments. His feelings about America and about Israel were passionate. After leaving the Senate he led United Against Nuclear Iran, a group fervently opposed to Barack Obama’s Iran deal and to Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. He viewed that development as a mortal danger to the Jewish state. But when we met to discuss that danger and the steps we could take to avoid it, gloom was never the prevailing mood and personal criticisms were off the table. The questions were always what’s happening now and what positive steps can we take.

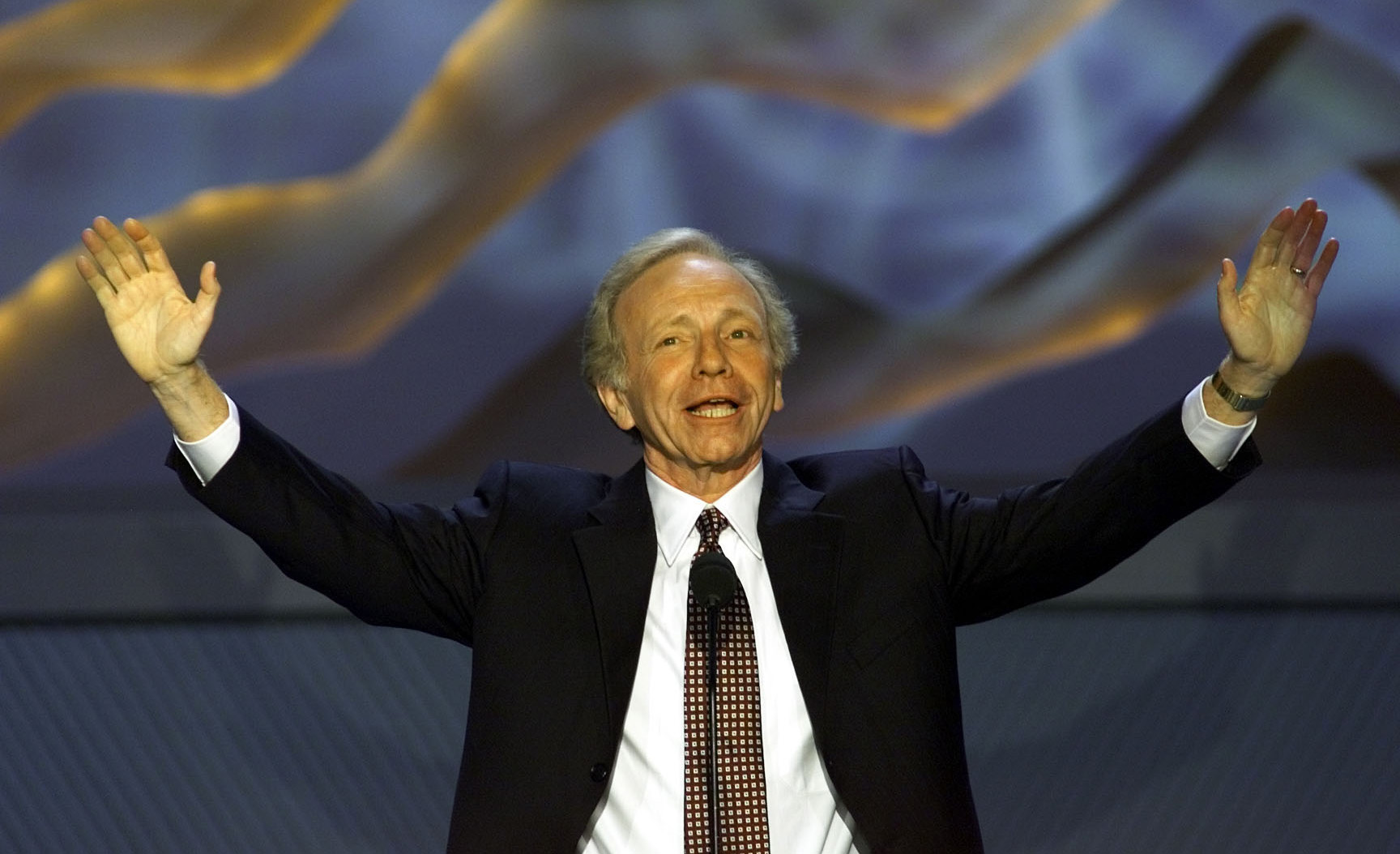

Lieberman was a historic figure in American Jewish history in two senses. His nomination for the vice- presidency in 2000 was the first time a Jew had been on a major party ticket. That would simply have been unthinkable only a few decades before, when Lieberman entered public life. His nomination was an extraordinary milestone for the American Jewish community, reflecting full acceptance of what before World War II had for the most part been a fairly recent immigrant group. The assimilation of American Jews—marked by their move from urban ghettos to the suburbs, the diminution in antisemitism in the 1950 and 1960s, and by the American adoption of terms like “Judeo-Christian values”—was in good part a post-war phenomenon. Yet in only two generations, here was a Jew running for vice-president.

But Lieberman’s nomination was not about assimilation, and that was the second way in which he was so important. As an Orthodox Jew, assimilation was the last thing he had in mind. His career and his life carried an additional meaning: that an Orthodox Jew, a faithful and observant Jew, could succeed fully in America without assimilating and leaving behind his religion. Indeed many faithful Christians saw in him a reflection of their own religious commitments and viewed him as an ally: a God-fearing man working to keep his faith and to reflect its values in his life and in the life of the nation. For Orthodox Jews, Lieberman’s successes were an answer to a very old argument: that religious observance had to be dropped or compromised to “make it” in America.

Orthodox in religion, Lieberman was unorthodox in politics by the time he ran for re-election to the Senate in 2006, when he was denied the Democratic nomination and won as an independent. That unorthodoxy was visible most clearly in the 2008 presidential election, when he endorsed his friend John McCain for president. Here was the Democratic vice-presidential nominee of 2000 endorsing a Republican only two elections later. Remarkable, unheard-of, disloyal? For Joe Lieberman, it was a matter of patriotism: “Being a Republican is important. Being a Democrat is important. But you know what’s more important than that? The interest and well-being of the United States of America.”

That was not just a campaign speech but a true statement of Lieberman’s approach to his role in public life. He knew he was drifting from his party when he supported the war in Iraq, but so what? Party loyalty could not outweigh what was best for America as he saw it. He knew his push for a tough position on Iran was an uphill battle but he thought it was crucial for the security of Israel. He knew his conduct would reflect on all American Jews because he was one of the most prominent Jews in America—and for many years, the most prominent. So he carried himself with pride and commitment to Judaism, but always without rancor. Look at the photos of him in the media today, and most show him with the warm and slightly self-deprecating smile that reflected his character.

There was no one in politics in his lifetime who did more to remind us of those “better angels of our nature”—of how politics could be conducted with principle and tolerance. Joseph Lieberman will be missed for many reasons, and that is not the least.