Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

We’re still months away from the autumn Holy Days, but Leo Staschover is already thinking of them. He writes:

Here is a language question that no rabbi or cantor I’ve put it to has been able to answer. Why, after the blowing of the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, do we say [using the masculine form of the Hebrew verb arav, to be pleasing] areshet s’fateynu ye’erav lefanekha [“May the areshet of our lips be pleasing to You”] rather than te’erav [the feminine form]? Isn’t areshet feminine?

Indeed it is. But before we discuss its grammatical gender, something needs to be said about its meaning. Areshet is a biblical word found a single time in all of Scripture, in the book of Psalms—which makes it, using the traditional Greek term for such singularities, a hapax legomenon, a “said only once.” Hapax legomena are often textually problematic because their meaning can be difficult to pin down, especially when we can’t relate them to other words.

Imagine, for example, encountering in an English book a word you’ve never seen before: let’s say “grandle.” If it’s in a sentence like “She put tomatoes, cucumbers, and grandles in the salad,” you can reasonably assume that a grandle is a vegetable or salad green, and if the word turns up in a second sentence that goes, “The grandles’ succulent buds were ready to be picked,” you know what part of the grandle is eaten; moreover, with every additional mention of grandles, your knowledge of them grows.

Yet suppose “grandle” occurs only once, in a sentence like “There was a grandle on the table.” Now you’re stuck. Without a dictionary at hand, you have no way even of guessing what a grandle might be.

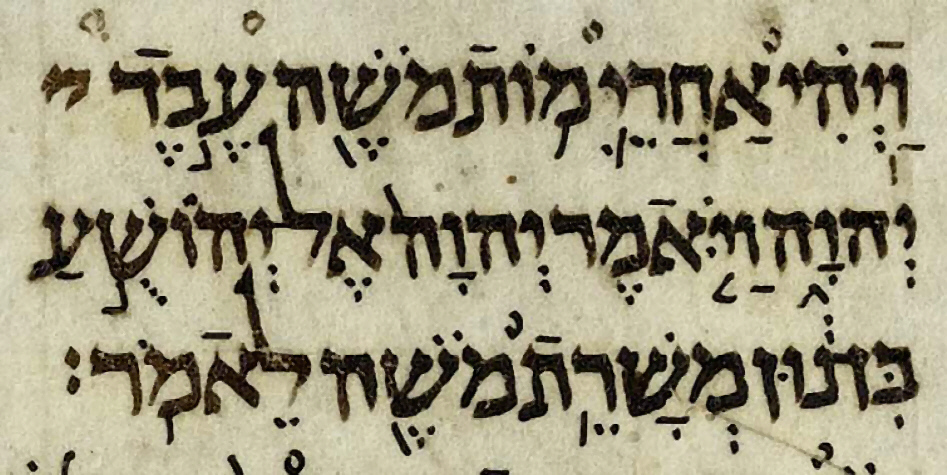

Although the biblical word areshet, spelled alef-resh-shin-taf, is found only in Psalms 21:3 and has no known Hebrew root, it isn’t as enigmatic as a grandle on a table. The first half of Psalms 21 is a hymn to a righteous monarch, the second and third verses of which read, in the King James Version, “The king shall joy in Thy strength, O Lord, and in Thy salvation how greatly he shall rejoice. Thou hast given him his heart’s desire, and hast not withholden the request of his lips.” Inasmuch as the poetry of Psalms, like most biblical poetry, is structured by having the second half of each line restate the first half in different language, the Hebrew phrase rendered as “the request of his lips,” areshet s’fatav, must be parallel to “his heart’s desire” and mean much the same thing.

On the basis of this clue alone, the King James Version would have been guessing intelligently by translating areshet as “request.” It also, however, had previous translations and commentaries to guide it. These included the Greek Septuagint’s déesis, “entreaty”; the Aramaic Targum’s perush, “utterance”; the Latin Vulgate’s voluntas, “will” or “wish”; and a host of medieval Jewish exegetes, most agreeing with the Targum. In the end, the King James chanced to hit the nail on the head, since today we know, thanks to the deciphering of archeologically unearthed texts, that areshet is a cognate of ancient Phoenician irsh and Akkadian ereshtu, both meaning “request.”

But how, since the biblical areshet has no accompanying verb or adjective to indicate its gender, do we know that it is, as Mr. Staschover correctly asserts, grammatically feminine? The answer is that nearly all Hebrew nouns ending in taf are feminine, and that the few exceptions, such as mavet, death, or ot, sign, do not share areshet‘s pattern of consonants; all the many words that do, such as parokhet, “curtain,” kadaḥat, “fever,” kutonet, “tunic,” gaḥelet, “hot coal,” etc., are feminine in every respect. Mr. Staschover’s question about the Rosh Hashanah liturgy is thus a good one.

The only plausible explanation I can give him for the ungrammatical Hebrew of the prayer is that of a scribal error. This could have happened in two ways. One would have been for the yod of ye’erav to have been inadvertently switched for the taf of te’erav by a scribe who was momentarily dreaming. The other would have been for the original prayer to have had eresh rather than areshet s’fateynu, the former being a masculine form of areshet coined by the paytanim, the Hebrew liturgical poets of the early Common Era. An absent-minded copyist might have changed eresh to the more common areshet without noting that this also called for changing ye’erav to te’erav.

But how, you may ask, could subsequent copyists not have noticed the error and rectified it? Precisely here lies the paradox of the transmission of sacred texts. On the one hand, the scribes of such texts take great pains to copy them faithfully. At the same time, though, any error creeping into them is likely to become permanent, since it quickly gains sacred stratus in its own right. Once ye’erav replaced te’erav, or areshet replaced eresh, no scribe dared to correct it, even though it was obviously wrong.

Take a similar grammatical error—this one in the Bible itself, though it subsequently entered the Jewish prayer book as well: the verse from Proverbs, sung or recited in the synagogue while returning the Torah to the Ark, ets ḥayyim hi la’maḥazikim ba v’tomkheha me’ushar, “It [the Torah] is a tree of life for those who grasp it and happy are its upholders.” Although the rules of Hebrew grammar decree that any adjective qualifying the plural noun “upholders” must take the plural, too, so that “happy” should be me’usharim, the plural ending –im was carelessly dropped by a scribe already in biblical times, leaving us with me’ushar in the singular. To the Hebraically attuned ear, the result sounds the way “happy is its upholders” would sound in English. Yet for thousands of years the words have been passed down in this fashion, and it’s the same with areshet s’fateynu.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Hebrew Bible, Psalms, Religion & Holidays