Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Ruth Fath writes from Princeton, New Jersey:

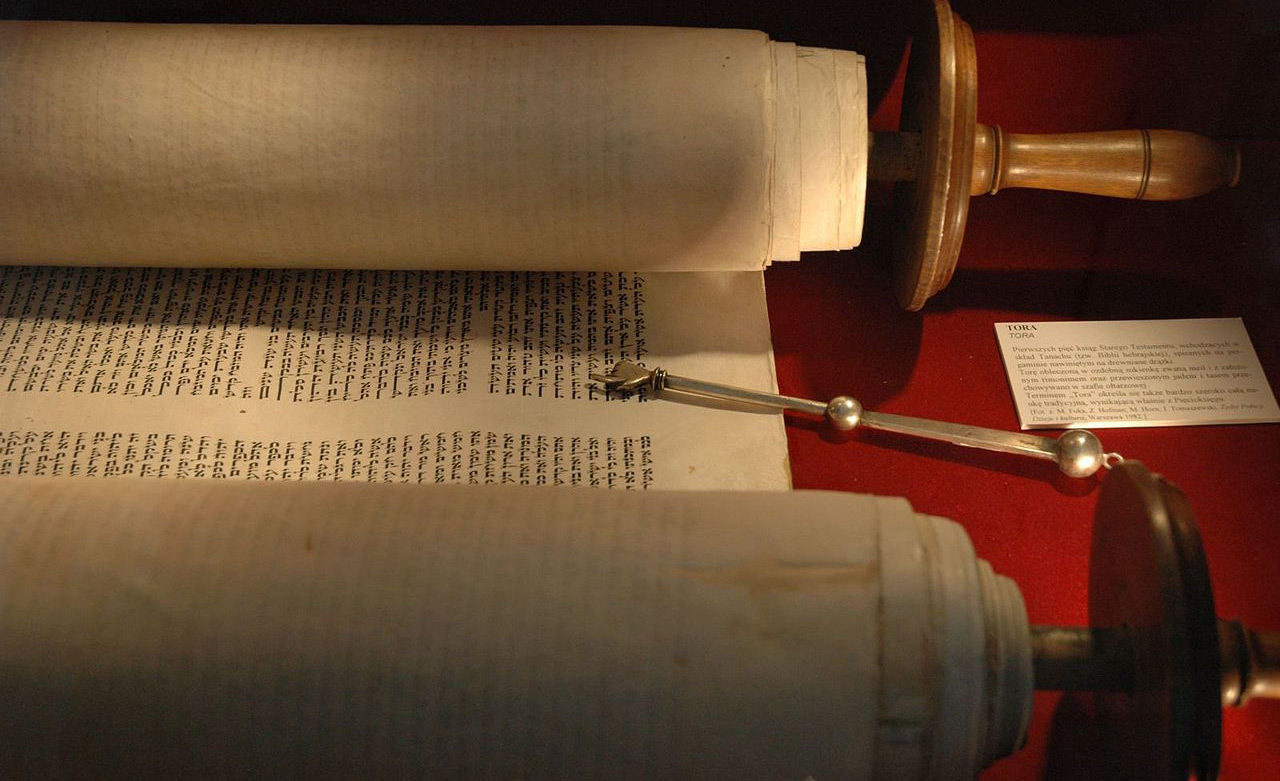

Recently, after my husband’s death, I donated to our local Jewish Center a very old Torah scroll that we had bought many years ago. With it, I also gave the Center two yadayim, as I thought they were called. When I mentioned them to our cantor and Torah reader, however, she corrected me and said they should be called yadot. Others have told me I was right and she was wrong. What is the correct plural form of yad when referring to the pointer used in reading the Torah?

A Torah pointer, held by the reader to keep track of his or her place in the parchment scroll of the Pentateuch, is called a yad, Hebrew for “hand,” because it traditionally takes the form of an arm with a hand, its fingers curled in a fist except for a pointing forefinger. And the regular Hebrew plural for yad is indeed yadayim, –ayim being a special dual ending for items that come in pairs. (The standard plural ending in Hebrew is either –im or –ot.) In pre-biblical times, presumably, such an ending was used, as it still is in the dual ending of –eyn in Hebrew’s fellow Semitic language of Arabic, for two of anything, whether houses, goats, or watermelons. But this feature had already vanished from the Hebrew of the Bible, in which the dual plural is restricted to a fixed and not very large number of words and cannot be freely applied.

Although this is the situation in contemporary Hebrew, too, many of the words that do take the dual plural are common, everyday ones. The largest group of them pertains to body parts, as in ozen, ear, plural oznayim; katef, shoulder, plural k’tefayim; berekh, knee, plural birkayim; and so forth. Others categories pertain to numbers (me’ah, hundred, ma’tayim, two hundred; pa’am, once, pa’amayim, twice); units of time (sha’ah, hour, sha’atayim, two hours; yom, day, yomayim,“two days); and coupled objects (kav, crutch, kabayim, crutches; m’tsilah, gong, m’tsiltayim, cymbals). Some anomalous dual plurals—like shamayim, sky, mayim, water, and tsohorayim, noon—have no singular form and function in both capacities like the English fish and deer. And while, for the most part, the dual ending has ceased to be productive in Hebrew, new words have occasionally continued to be coined with the help of it even in modern times, such as ofanayim, bicycle, from ofan, wheel, and n’kudotayim, colon (the punctuation mark), from n’kudah, point.

Yet the Princeton Jewish Center’s cantor is right. Torah pointers in Hebrew are yadot, not yadayim. The reason for this is not difficult to discern. Unlike hands, Torah pointers do not come in pairs, so that a dual ending for them would not be logical. Indeed, this is the rule for all body-part duals having other, secondary meanings. Safah, for instance is the Hebrew word for lip, in which sense it takes the plural s’fatayim; but it also means language (compare the similar double meaning of English “tongue”), and when it does, its plural is safot. Or take kaf, palm (of the hand), whose plural is kapayim. It also, though, denotes a spoon (the physical resemblance is obvious), and spoons are kapot.

Still another example is one with which some of you may be more familiar. Regel in Hebrew (dual plural raglayim) means leg or foot, but when it takes a non-dual plural in the phrase shalosh ha-regalim, “the three regalim,” it refers to the three holidays of Sukkot, Pesaḥ, and Shavuot on which Jews made the pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. (The expression comes from the Hebrew words for pilgrimage and pilgrim, aliyah l’regel and oleh regel, which might be translated as “an ascent on foot” and “an ascender on foot,” although not all scholars would agree with this.)

In a word: one hand is the same as one Torah pointer, but many Torah pointers are different from many hands. That’s the long and short of it.

***

I can’t resist sharing with you the following letter, sent in response to my remarks two weeks ago about the Hebrew/Yiddish drinking chant eleh toldoys noyakh. It comes from David Goldenberg, who writes:

Your last column on bilingual or even trilingual rhymed couplets reminded me of an incident from my youth. In the old-fashioned school I went to, we were taught Bible, starting with the story of Creation, by declaiming first the Hebrew and then its Yiddish translation in a typical sing-song chant, e.g.: “Breyshis, in onfang [in the beginning], boro eloykim, hot got beshafn [God created], es ha-shomayim, di himl [heaven] . . .”

When I was still in elementary school, I landed my first job, which was tutoring a young boy just starting out in school who had difficulty in learning his Bible. By this time, bilingual ḥumesh-taytsh [Yiddish-Hebrew Bible translation] had transmuted into trilingual Hebrew-Yiddish-English, so that the boy had to learn: “Breyshis, in onfang, in the beginning, boro eloykim, hot got geshafn, God created,” etc. In one lesson, we came to the verse “Vayaker Yehuda, un Yehuda hot derkent, and Judah recognized.” No matter how many times we went over it, the boy couldn’t remember the Yiddish word derkent. Finally, having met the boy’s father, I tried a mnemonic device and said: “Your father smokes cigarettes. What brand does he smoke?” A light went on in my pupil’s mind. “I get it” he exclaimed. “He smokes Kent!” And this time, asked by me to repeat the verse once again, he chanted: “Vayaker Yehuda, un Yehuda hot derkent, and Judah smoked.”

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Hebrew, Religion & Holidays