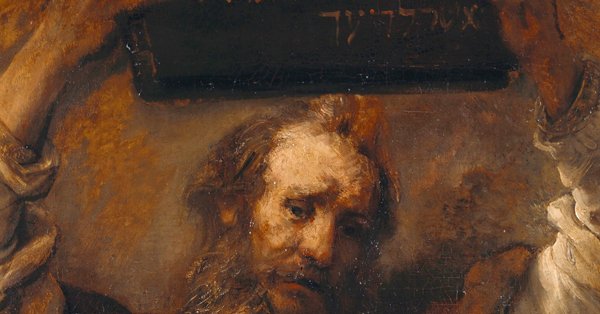

A detail from Moses with the Ten Commandments by Rembrandt, 1659. Wikipedia.

As Jews the world over prepare to celebrate Shavuot, the anniversary of the giving of the Law, few biblical scenes are more appropriate to contemplate than the spectacle of Moses bringing the tablets of the Ten Commandments down from Mount Sinai. And, incongruous though this may seem to many Jews, no more appropriate image of the scene exists than Rembrandt van Rijn’s depiction of the prophet holding aloft the two tablets bearing their Hebrew inscriptions (1659). Not only strikingly beautiful, the painting also happens to be one of the most authentically Jewish works of art ever created.

How so?

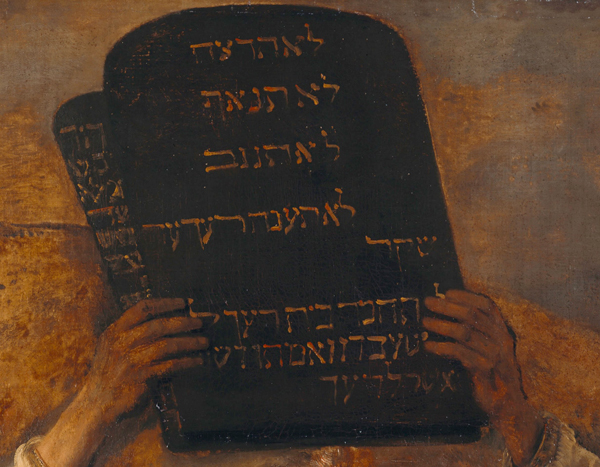

The full view of Rembrandt’s Moses with the Ten Commandments. Click for a bigger view.

For one thing, the great Dutch master corrected the exegetical and sculptural error committed by Michelangelo in the most famous depiction of Moses in the history of art. The book of Exodus describes how, descending from Sinai, Moses was unaware ki karan or panav. Through a mistaken analogy to the word keren, “horn,” Christian Bible commentators took the word karan to mean “horned,” leading to the “horns of light” seen on the head not only of Michelangelo’s Moses at the tomb of Pope Julius II but of other artistic renderings of the prophet throughout the centuries. Not, however, Rembrandt—who clearly understood that the most accurate translation of the biblical phrase has Moses unaware that his face “shone,” just as it shines in this painting. As the historian Simon Schama has written, the very darkness of the painting’s surrounding scene “only makes such light as there is shine with greater intensity.”

A detail of Michelangelo’s Moses, c. 1515. Wikipedia.

Schama also notes a further corrective of the common misunderstanding, namely, Rembrandt’s transformation of the horns, a widespread feature in contemporary European prints of the scene, into “tufts of hair in the center of [Moses’] pate.” Rembrandt’s Moses is not an especially handsome individual, but neither is he in any way ugly. He is a normal human being, whose face, unbeknownst to him, has become bathed in a divine luminance.

And that makes those winsome tufts of hair, nothing but a few small dabs of paint, significant in another way as well: as an example of Dutch art’s “normalization” of the Jews. In Rembrandt’s Jews, Steven Nadler reminds us that in much medieval and Renaissance art, “the Jew is not merely morally degenerate, but of a sinisterly different nature altogether.” With “bulging, heavy-lidded eyes, hooked nose, dark skin, large open mouth, and thick, fleshy lips,” Jews are made to look “more like cartoon characters than natural human beings.” And then suddenly, Nadler writes,

we come to 17th-century Dutch art, where we find . . . nothing; utter plainness. . . . . Ugliness and deformity are there, but they represent the common sins and foibles of all of humankind. . . . More than a century after their political emancipation in the Netherlands, the Jews experienced there an unprecedented aesthetic liberation.

Tufts of hair on the head of Rembrandt’s Moses.

Moses’ face and forehead exhaust Rembrandt’s deep sympathy with Jews and Jewish tradition as exhibited in this artwork. Let’s take a closer look at the tablets themselves. True, they are rounded, whereas rabbinic tradition insists they had squared edges. But many synagogues nevertheless depicted the tablets as round, among them the Bevis Marks synagogue, opened in 1701 and the oldest in Britain.

In any case, the real Jewishness of Rembrandt’s tablets lies not in their shape but in their lettering. For an artist who did not read Hebrew, Rembrandt’s calligraphy is both exquisite and exquisitely faithful, and the spelling almost perfect. Even among his Dutch contemporaries, this was unusual; often in their work, Hebrew script is rendered in caricature. But here, too, Nadler writes, Rembrandt “was different”: indeed, “no other non-Jewish painter in history . . . equaled his ability to make the Hebrew—real Hebrew—an integral element of the work.” Most noteworthy in this painting is the letter bet in the eighth commandment, lo tignov (“Thou shalt not steal”); in order to keep the line even with those above it, the horizontal ends of the letter are elongated exactly as a sofer, a Torah scribe, would do.

And there is more. Consider next the placement of the commandments on the tablets themselves. While the first tablet is largely obscured from the viewer’s sight, the text on the second tablet begins with lo tirtsaḥ: the ban on murder that is otherwise known as the sixth commandment.

Rembrandt, then, assumed that the commandments were evenly divided, five on each tablet—to Jews, an arrangement taken utterly for granted but, in the context of that time and place, utterly revolutionary.

Images of the tablets hung in many churches in Holland, containing the words of the Decalogue in Dutch translation. But since the Bible itself nowhere explains which of the divine statements appear on which tablet, artists and churchmen took it upon themselves to decide how to distribute them. The standard practice was to present the first four, ending with the obligation to remember the Sabbath, on one tablet, with the remaining six, beginning with honoring father and mother, on the other. And there was a logic to this. After all, the first four statements seem to pertain exclusively to the relationship between man and God, while the rest, beginning with duties toward one’s parents, seem to focus on ethical obligations among human beings.

But the Jewish division adheres to its own, countervailing logic. For Jews, it was perfectly appropriate to include the mitzvah of honoring one’s progenitors on the tablet that is all about God, for father and mother are, themselves, reflections of God’s paternal love for humanity and for the Jewish people. In honoring parents, one is thus honoring God Himself.

Upon hearing his mother’s footsteps, Rabbi Joseph, a blind rabbi in the Talmud, would announce: “I rise before the coming of the sh’khinah,” the divine presence. Centuries later, that phrase inspired Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik to write:

Behind every mother, young or old, happy or sad, trails the sh’khinah. And behind every father, erect or stooped, in playful or stern mood, walks malka kaddisha, the Holy King. This is not mysticism. It is halakhah. The awareness of the sh’khinah results in the obligation to rise before father and mother.

Intentionally or not, Rembrandt’s five-and-five ordering, which implicitly restores the honoring of parents to the tablet that relates to God, testifies to the centrality of family at the heart of the Jewish relationship with the divine.

The tablets held by Rembrandt’s Moses.

That brings us to the next, somewhat more elusive link between this painting and Judaism. From the examples of Rembrandt’s familiarity with matters Jewish, one may easily infer the presence in his life of an actual Jewish connection. But who, in the case of this painting, could that have been?

It is well known that Rembrandt’s “rabbi” in Amsterdam was the Portuguese-born Menasheh ben Israel, whose family in 1610 had moved to Holland to escape the Inquisition and who himself became a prominent thinker, writer, and diplomat. His direct influence on Rembrandt’s earlier work Belshazzar’s Feast (1635) has been thoroughly documented. But he was no longer alive in 1659 when this painting was created. And yet, as the Israeli art historian Shalom Sabar has noted, it, too, is “strongly connected to the [Dutch] Sephardi community”—by, specifically, “a curious piece of evidence.”

Sabar’s piece of evidence is the coloring of both the tablets and the Hebrew letters. Ordinarily, one would expect black letters on white stone. Instead, Rembrandt has given us gold letters on black stone. Intriguingly, this aesthetic choice echoes the two tablets crowning the wooden ark in the Esnoga, the magnificent synagogue of the Portuguese Sephardi Jews of Amsterdam. These feature the same five-and-five division, and the letters “are made of copper laid in wood, their coloring and appearance also reminiscent of [Rembrandt’s] painting”—down to the beautifully elongated bet in lo tignov.

The catch here is that the synagogue was constructed several years after Rembrandt’s death, which means that the Jewish and Sephardi connection to his letters is at once obvious and mysterious. Someday, we may learn more about it.

One more question remains: exactly which biblical scene is Rembrandt depicting? Many art historians have assumed that Moses, having descended from Mount Sinai with the first set of tablets, and beheld the Israelites in riotous worship of the golden calf, is seen here hoisting the tablets over his head, poised to shatter them in a furious and indelible manifestation of the shattering of the divine covenant. Indeed, the title of the painting, sometimes given as Moses with the Ten Commandments, perhaps more frequently appears as Moses Breaking [or Smashing] the Tablets of the Law.

Moses’ face, however, does not appear all that angry. Besides, as Schama observes, “the Bible makes it clear that Moses breaks the tablets not when he is [still] on the mountain, but after he has come ‘nigh unto the camp’ and seen ‘the calf, and the dancing.’” Even more significantly, the miraculous “rays of light” to which the painting plainly alludes are associated in the Bible precisely with the second set of tablets.

To Schama, what Rembrandt “means us to imagine, at the foot of Mount Sinai, [is] the gathering of penitent sinners who, despite their wantonness, had been given, through the favor that Moses found with the Lord, their covenant.” He adds, again plausibly, that for Rembrandt this manifestation of divine mercy would also have “most closely corresponded to the Calvinist doctrine of salvation by grace alone.” And he points to still another fact: that Mount Sinai in the painting is colored a tawny brown monochrome with “the figure of the prophet coarsely clad and rough-cast as though extruded from the stone himself”—a fact to which Schama attaches mainly aesthetic significance but which we may see as uncannily yielding a final instance of a specifically Jewish theme.

As Rembrandt, a careful reader of the Bible, might have noticed, the first set of tablets was given directly by God, but the second set was carved by Moses—or, one might say, was extruded by Moses from the stone itself. The human effort required to create the second set, the set that restored the covenant, brings to mind a paradox eloquently described by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. The first tablets, Sacks comments, “were perhaps the holiest object in history: from beginning to end, the work of God. Yet within hours they lay shattered, broken by Moses when he saw the calf and the Israelites dancing around it.” The second tablets, carved by Moses with the letters once again engraved by the fiery finger of God, were eternal.

Here lies an anomaly. “Why,” asks Sacks, “was the more holy object broken while the less holy stayed whole?” The answer:

Receiving the first tablets, Moses was passive. Therefore, nothing in him changed. For the second, he was active. He had a share in the making. He carved the stone on which the words were to be engraved. That is why he became a different person. His face shone. [Emphasis added]

God’s miraculous intervention changes the universe, but only our own partnership in the covenant changes us.

In his own essay on the painting, Shalom Sabar cites the suggestion of previous scholars that the image of Moses holding the tablets above his head may have been influenced by a visit to a synagogue where Rembrandt could have witnessed the ceremony of hagbahah, the raising and display of the open Torah scroll. Whether true or not, the suggestion recalls the standard verse recited during this same ritual: “And this is the Torah that Moses placed before the children of Israel.” Moses is given credit for the Torah, and rightly so, as it is he who painstakingly carved the second tablets and thereby restored the covenant between God and Israel.

In brief, of all the Jewish elements in this extraordinary painting, the most genuinely Jewish may be the image of Moses extruding from the mountain the very word of God: the same divine word whose bestowal upon the Jewish people is celebrated every year on the festival of Shavuot.