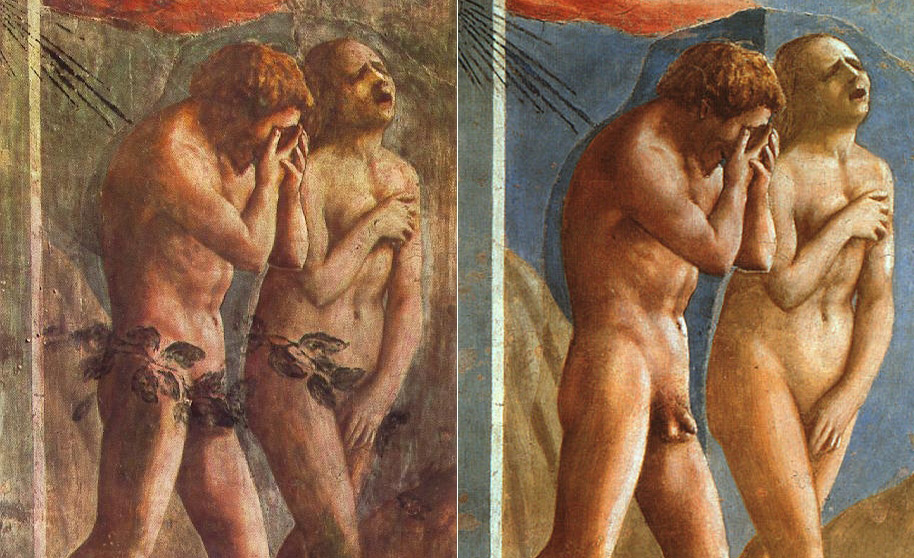

From The Expulsion Of Adam and Eve from Eden by Masaccio. 1426-1428. Altered in 1680, left frame; restored in 1980, right frame. Wikimedia.

The human story in the Bible begins in a garden with Adam and Eve and a mysterious tree: the tree of knowledge of good and evil. God, Who has created the pair and planted the garden, gives them a single prohibition: not to eat from that tree on pain of death. Yet Eve, egged on by the snake who assures her they will not die but instead become like God Himself, eats from the tree and offers some to Adam, who partakes as well.

Immediately upon eating, the couple, who till then had been “naked but not ashamed,” clothe themselves and try to hide from God’s wrath. Anticipating that they might next eat from a second tree, the tree of life, God punishes and expels them, stationing cherubim with flaming swords at the entrance to the garden so they can never return.

What is the tree of knowledge of good and evil? If we look at five puzzles arising from the story of Adam and Eve, together they may help yield an answer.

- At first God prohibits the tree of knowledge and only later banishes the humans lest they eat as well from the tree of life. What is the meaning of that order? Why not prohibit the tree of life first?

- God tells Adam if he eats of the fruit he will die. He and Eve eat, but do not die. Why not?

- Why is Adam and Eve’s first reaction to eating from the tree of knowledge to become ashamed of their nakedness and to clothe themselves?

- Why after leaving Eden is the couple’s first act to conceive a child?

- In what sense are human beings expelled from paradise?

Generations have explored and explained this story, which is one of the world’s best known, and all five questions have been taken up and responded to by centuries of rabbis, commentators, and theologians. Let’s try to see them here in terms of the human struggle with finitude—a subject on which, in its typically brief and cryptic fashion, the Bible discloses almost unfathomable depths.

The Denial of Death, by the social psychologist Ernest Becker, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1974. According to Becker, it was not sex, as Freud had postulated, but death that underlies our human experience—and specifically the fear and denial of our own mortality. If anything, our obsession with sex hides a deeper obsession with death since, like eating and bathroom functions, sex reminds us we are bodies, and bodies are what decay and die. (La petite mort, the French call the sensation of orgasm.) Like animals we eat, eliminate, and procreate. Indeed, for Becker, everything from table manners, to disgust with our own waste, to the endless dance surrounding sexuality is an attempt to deal with the reality of being mortal bodies.

From there, Becker proceeds to reach a number of large conclusions about the fundamental human condition. One need hardly agree with these to recognize that what we share with animals reminds us uncomfortably of our physicality and our corporeality. We have trouble with the underlying paradox of our existence: you can be thinking the most exalted thoughts, but if your body makes an insistent demand, it must be obeyed. In Jewish law, a dead body is av tum’ah, the greatest source of ritual impurity.

Think back now to the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which in this view is actually the tree of the knowledge of death. If we lived forever, things would be neither good nor bad. A broken friendship could be restored next century, or you could lose weight in your three-hundreds. And here’s an answer to our first question: the tree of life was not prohibited earlier because Adam and Eve did not think to eat of it: death was unknown to them.

By contrast, when they ate of the prohibited tree, the tree of knowledge of good and evil, they did die. Not in a literal sense but in a psychological sense—as we all do the first time we take into our consciousness that things fade and break and die.

Similarly with our other questions: in becoming aware of their corporeality, the human couple seek out clothing. The paradise they lose is the paradise of permanence. Now recognizing their mortality, they conceive a child, thereby reaching for immortality.

It emerges, then, that Genesis not only brilliantly elaborates the fundamental human dilemma but also suggests the remedies. There are at least three.

“Therefore a man will leave his father and mother and cling to his wife” (Genesis 2:24). This is what Adam and Eve do in response to God: they “leave” Him and cling to each other. Thus one of the answers to death is love. As the Song of Songs puts it succinctly later in the Bible, “Love is as strong as death” (8:6). Or, as a modern American poet would have it (doing a turn on Paul in the New Testament book of Romans), “the wages of dying is love.” And a second answer to death is procreation, to have a child to carry on.

The ultimate religious answer to death is placed at the very moment of creation. In forming the human being, God “breathes the breath of life” into him (2:7). In other words, the source of life comes from beyond ourselves. This is one of the verses used by the talmudic sages to prove the concept of the soul’s life after death. For if life comes from beyond, it is not extinguished when the body fails.

Is, then, the Garden of Eden story a parable of the fall, of “original sin”? Not quite. The Jewish prayers insist each morning, “God the soul You have given me is pure.” Rather, the story tells us of the most difficult feature of life—its temporality—and the remedies both given and sought. The story of Adam and Eve explains the gift of life, the dilemma of death, the human need to reach beyond the grave, and the religious promise of eternity.