If the first chapters of Genesis explore the universal origins of humanity, this week’s Torah reading of Lekh l’kha (Genesis 12-17) turns to a more particularistic narrative. Beginning with God’s command to Abraham to uproot himself from his father’s home and travel to an unknown land, it caps the command with a divine promise:

I will make of you a great nation,

And I will bless you;

I will make your name great.

And you shall be a blessing.

I will bless those who bless you

And curse him that curses you;

And all the families of the earth

Shall bless themselves by you.

To this, God adds: “I will assign this land to your offspring.”

But there is one problem: Abraham and his wife Sarah are unable to have children.

Thus, the very beginning of the Jewish people’s existence is framed within the context of marriage and of marital discontent. If Sarah can’t conceive, the fulfillment of God’s promise is in jeopardy. Both Abraham and Sarah must struggle to reconcile that promise with their immediate reality. Although they will ultimately overcome this and other tests of faith, Sarah’s conduct in particular has been subjected to censure in both traditional and more modern Jewish sources.

The critical episode occurs about ten years after the initial promises of Lekh l’kha. Sarah is advancing in years and has yet to conceive a child. Unbidden by God or by Abraham, she offers her Egyptian maidservant Hagar to her husband as a concubine. He accepts, and soon afterward Hagar conceives.

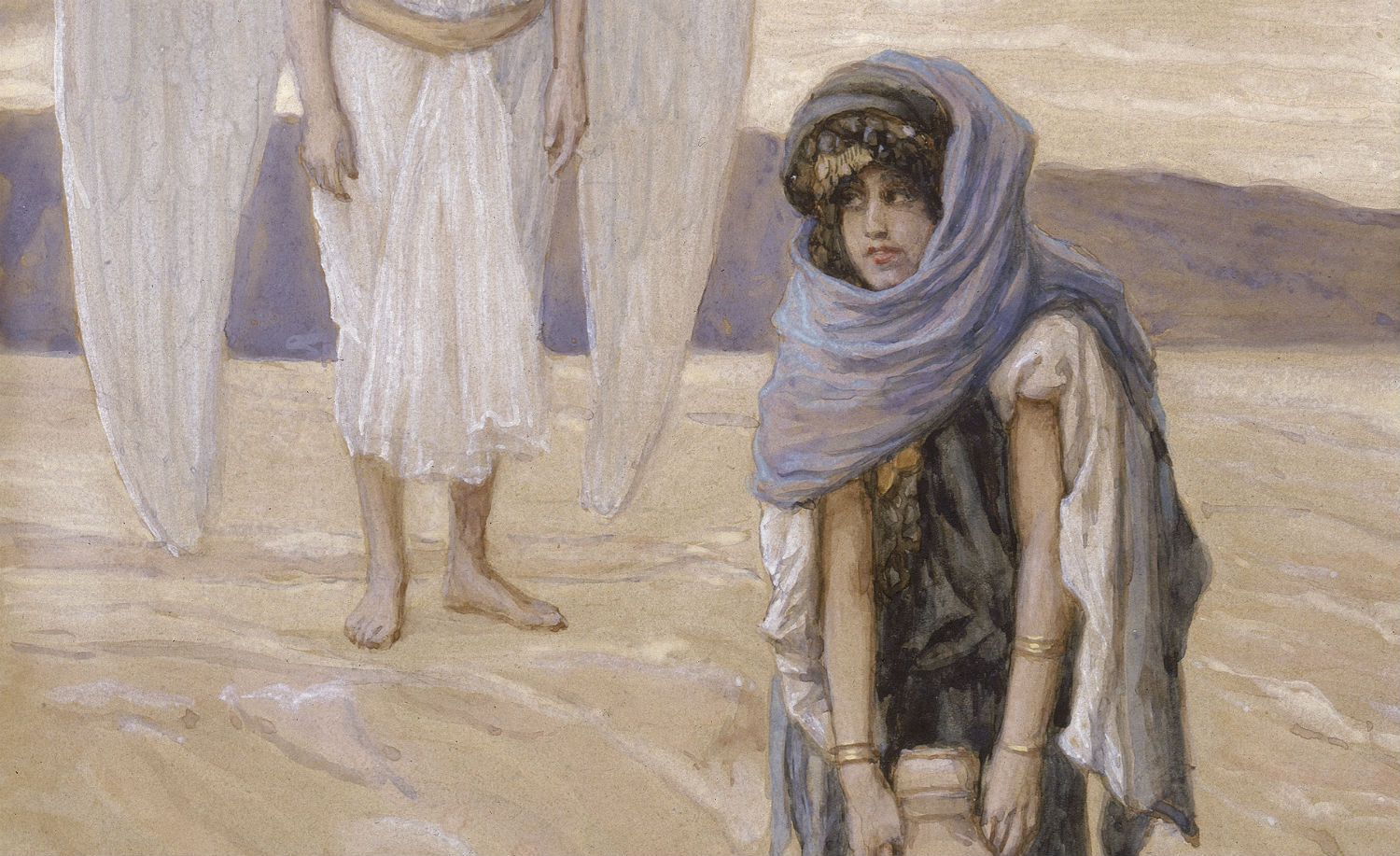

Unsurprisingly, the pregnancy becomes a source of domestic tension. Hagar, exploiting her now-elevated status, grows disrespectful toward Sarah, and in response Sarah treats her harshly. To escape her mistress’s heavy hand, Hagar flees to the wilderness, where she is met by an angel of God who blesses her and tells her to return to Abraham’s camp.

The denouement, in the reading following Lekh l’kha, unfolds when Sarah becomes pregnant with her own son, Isaac—which, however, only exacerbates the domestic tensions. Ultimately she instructs Abraham to banish both Hagar and her child Ishmael. Abraham, anguished at this prospect, finally relents when instructed by God that “Whatever Sarah tells you, do as she says,” and sends both mother and child away.

Despite God’s direct approval of Sarah’s behavior, Jewish commentators have long expressed ambivalence over it. The 11th-century sage Rashi emphasizes the cruelty of Hagar’s treatment at Sarah’s hands. Writing two centuries later, Moses Naḥmanides, building on the commentary of David Kimḥi, states bluntly that Sarah sinned in afflicting Hagar. Although other rabbis have risen to the matriarch’s defense, many modern commentators, for their part, have tended to find Sarah’s behavior even harder to justify.

Sarah’s actions might be better understood by looking at a seemingly unrelated subplot that spans this and next week’s readings but that has not received the same sort of censure: namely, the story of Abraham’s nephew Lot. An orphan, Lot has followed Abraham to Canaan and, because of his proximity to the patriarch, received special divine blessing. In contrast to Sarah’s callous treatment of Hagar, Abraham’s conduct toward his nephew is at worst prudent, at best selfless and heroic. Even so, Lot is never regarded as a potential heir. Precisely for this reason, the Lot narrative makes for a perfect comparison with the Hagar-and-Ishmael narrative.

In analyzing the two stories, it is crucial to bear in mind that Lekh l’kha narrates not only one national beginning—that of the Jewish people—but also the beginnings of three other nations who would historically live near Israel’s borders: the Arabs, descendants of Ishmael, plus the Ammonites and Moabites, peoples who lived in what is now Jordan and each of whom is descended from one of Lot’s two sons. Like Ishmael, then, Lot is a blood relative and member of Abraham’s household who, although ultimately read out of the grand narrative of the chosen nation, still benefits from Abraham’s election.

While following his uncle on his journeys, Lot has become, like him, the owner of much livestock. But when their respective shepherds begin to quarrel, Abraham senses that it might be wise to part ways. Lot heads toward the then-lush plain at the mouth of the Jordan, leaving Abraham with the literal and figurative high ground in the hills of Hebron.

Lot’s chosen abode, the morally corrupt territory of Sodom and Gomorrah, reveals something about his character. When his association with his neighbors endangers his life—he is captured by conquering Mesopotamian potentates—Abraham swoops in to save him. Yet their reunification, like Hagar’s initial return, is temporary. Lot evidently goes back to Sodom, which is about to be destroyed for its wickedness; the biblical text gives no indication of any subsequent reunion with his uncle Abraham.

Numerous subtle cues invite the reader to juxtapose Lot and Hagar. In leaving Abraham’s camp, Lot chooses the cities of the plain because the land is fertile and well-irrigated “like the land of Egypt.” In running away from Abraham and Sarah’s camp, Hagar, too, who is of Egyptian extraction, ends up at “a well of water” in the wilderness. While Abraham spends most of his time on rocky hilltops, dependent on rain for sustenance, both Lot and Hagar are drawn to or connected with water flowing up from the ground.

The discrepant water sources may imply different relationships with nature as well as with God. In contrast to Egypt, where agriculture depends on the waters of the Nile and human systems of irrigation, a defining characteristic of the land of Israel, as Deuteronomy (11:10-14) makes clear, is that its crops require precipitation and thus God’s constant benevolent attention.

The parallels run deeper. Both Hagar and Lot interact with messengers of God (m’lakhim or angels), who save them from death. One such messenger rescues the dangerously parched Ishmael when he and his mother become lost in the wilderness; others come to Lot to warn him of Sodom’s imminent destruction. After Hagar’s salvation, the angel assures her that Ishmael will be the progenitor of “a great nation”; likewise, Lot after his rescue begets his sons Ammon and Moab. Even God’s promise to Abraham that he “will be a blessing” and that “all the families of the earth will bless themselves” by him may in part imply the proliferation of non-Israelite nations emerging from his own family.

In typically biblical fashion, there may also be a linguistic connection between Hagar’s and Lot’s narratives. In this case, it may be found in the repetition of a key Hebrew root: ts-ḥ-k, meaning to laugh or jest.

Soon after the birth of Isaac, Sarah understands that the time has come to part ways permanently with Hagar when she sees Ishmael m’tsaḥek—playing or mocking. The word also appears in the story of Lot, who is seen by his sons-in-law as a m’tsaḥek—a joker, a wise-guy, or perhaps even a clown—when he tells them that angels have informed him that Sodom is about to be destroyed. Whatever its exact meaning—the King James Version has “one who mocked”—to be such a person is not a good thing.

Yet also deriving from this same root is the name Isaac (in Hebrew, Yitsḥak), as both Sarah and Abraham separately laugh when they first hear, from divine messengers, that Sarah will bear a child at the age of ninety. Indeed, the particular form m’tsaḥek appears only three times in the Bible: once each to describe Ishmael and Lot, two persons who could have been but are not Abraham’s heirs, and a final time to describe Isaac, who is that heir but who gets into trouble when he is spied “sporting” (flirting?) with his wife Rebecca by the Philistine king Abimelech.

Clearly, then, the word sometimes connotes something positive and at other times something sinister, and both usages can occur in close proximity. Thus, while God seemingly condones Abraham’s laughter (17:17), He rebukes Sarah for hers (18:13). Yet God Himself seems to choose Isaac’s name, and Sarah’s declaration upon his birth—“God has brought me laughter (ts’ḥok); whoever hears [the good news of my son’s birth] will laugh (y’tsaḥek) for me”—seems to be a pious statement.

Somehow, then, the term for laughter must be wrapped up in the enterprise of understanding why Isaac is “in” and why Lot and Ishmael are decidedly “out.”

If there is a common thread here, it is the issue of faith.

Lot seems like “one who mocks”: fatally for them, both he and his sons-in-law disbelieve the threat of divine retribution. Sarah, similarly, laughs at being told she will give birth at the age of ninety because the idea seems so preposterous; her laughter provokes divine anger since it, too, suggests a lack of faith—a failure to believe in God’s ability to do the impossible. “Is anything too wondrous for the Lord?” He asks her. By contrast, her laughter at the time of Isaac’s birth is an explicit acknowledgment of God as the source of her sheer yet improbable joy.

As has often been noted, the book of Genesis tells a tale of divine winnowing. Noah is selected from all mankind, Abraham from among Noah’s descendants, Isaac from among Abraham’s children, and Jacob from Isaac’s. Sarah may have erred in afflicting Hagar, but this was a direct consequence of a deeper error: insufficient faith in her own vitality and in God’s promises.

Only once this underlying error is rectified, and only once Sarah and Abraham have successfully distinguished and separated their own covenantal core family—a task whose import Sarah understands before her husband does, just as Rebecca will do before her husband Isaac—can they begin to enact their national destiny.

In doing so, they will in turn bestow blessing onto the individuals, and eventually the nations, around them. Those individuals include both Lot and Hagar, who even as they depart from the Abrahamic foundations remain shaped by their original relationship and will continue to be supported in their travails by the emissaries of God.

More about: Hebrew Bible, Lekh Lekha, Religion & Holidays