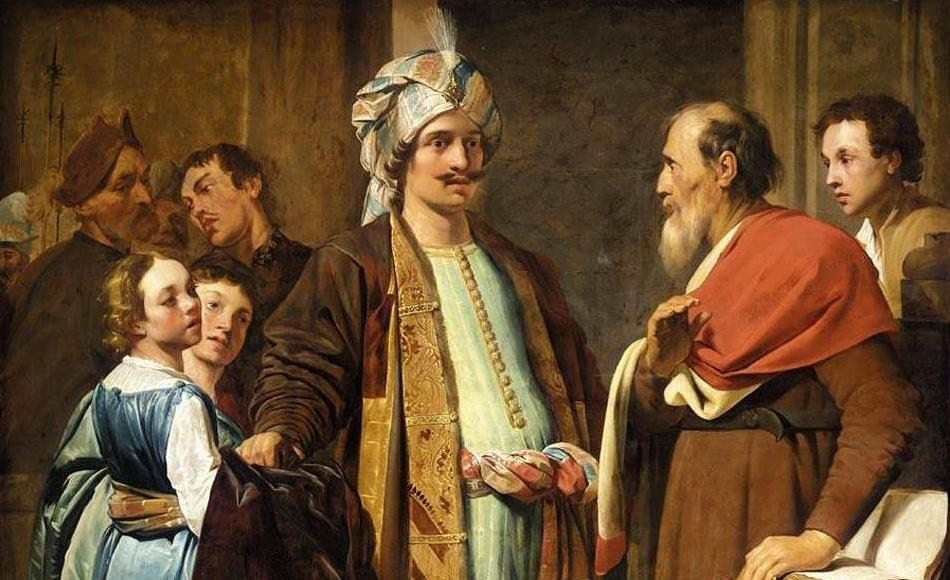

This Sabbath’s haftarah (prophetic reading) of 2Kings 4:1-37 tells the story of the prophet Elisha and his encounter with a wealthy woman, the lady of Shunem, and the miracles he performs for her in the course of their complex relationship. To make sense of this episode, we need to look back to Elisha’s final conversation with his great mentor, Elijah.

Just prior to being swept up to heaven in a chariot of fire, Elijah invites his disciple to present any final requests. Elisha boldly names his price: “Let a double portion of your spirit be given to me.” Subsequent passages will suggest that Elisha received his wish—which makes comparisons between the two prophets’ miracles inevitable. This is especially the case in the episode of our haftarah, which so clearly parallels an earlier event in the career of Elijah (1Kings 17).

In that earlier passage, which takes place in a time of drought and famine, the Lord instructs Elijah to go to a certain town where He has “commanded” a widow to provide for the prophet. But Elijah finds her and her son on the brink of starvation and about to consume their final morsels of food. He reassures the widow that if only she has faith and will agree to help him, her dish of oil and jug of flour will last until the drought ends. She believes him, takes him in, and all eat well—until her son becomes ill and dies.

The woman reacts with a bitter challenge. “What am I to you, man of God, that you come to me to find out my sin and put to death my son?” Elijah immediately takes the boy, carries him to an “attic” where he himself sleeps, lays the boy on his own bed, and, stretching out over him, calls to God—and the boy comes to life:

And the woman said to Elijah: “Now this proves to me

That you’re a man of God and the word of the Lord that you speak is true.”

Crucial here are two things: who does the asking and the nature of the giving. Elijah asks the widow for help; she resists; he persuades her by promising the miraculous assistance of God. When her son dies, her rebuke takes the form of a reasonable question: “Who asked you to come into my life with your miracles and their price—namely, the punishment of my sins through this death of my son?”

In response to this moral challenge, Elijah pulls the biggest possible prophetic rabbit out of a hat and calls on the Lord to bring back her son. Upon which, the widow still perceives their relationship as a kind of quid pro quo; but now that he’s performed the miracle, she’s had the ultimate proof that he really is who he said he was and hasn’t been playing her for a sucker. The scales have been balanced.

The parallel story involving Elisha is very different. His patroness, known only as the Shunamite woman, isn’t a starving widow but “a woman of substance.” And Elisha doesn’t find her; she finds him. “She wouldn’t let him go,” we are told, “until he ate her bread. And so whenever he passed by he’d turn in there and eat bread.”

This is quite the opposite of Elijah’s encounter with the widow who has to be persuaded to part with her mite. Here it’s she who asks him to allow her to provide. Something about Elisha elicits from her the desire to share her wealth.

And she doesn’t stop there, but suggests to her husband that they make, for this holy man of God, “a little loft with stairs, and put a bed and desk and chair and lamp there for him, so when he comes to us he can turn in there.” Elijah, too, had been given an attic room, but it’s only mentioned in passing. Here the lady is thinking actively about how to make Elisha comfortable—and not just in a garret but with a cozy space all to himself where he can be alone with his thoughts.

It is Elisha, and not the woman, who tries to introduce reciprocity into their relationship:

So he said to Gehazi his lad, “Call that Shunamite lady,” and he called her

And she came before him and he told him, “Say to her:

Look, you’ve fussed all this fuss over us—what can I do for you?

Is there a word you’d like me to say on your behalf

To the King or the commander of the army?”

To which the lady of Shunem replies with the most wonderfully pregnant phrase: “I’m dwelling among my own.” Not only does she feel no pain, but she feels no possibility of pain. She is surrounded by a world of people she can rely on.

But the prophet will not let it go. At this point, Gehazi points out that she is childless, and that her husband is old. So Elisha has him call the woman over; as she stands in the doorway, he says:

“When this date comes around again, you’ll be cuddling a son.”

But she said, “Don’t, milord, as a man of God, delude your servant.”

Here we have the nub of this relationship, which is silence. The prophet’s mind has been on higher things; he can’t imagine what he can do for this important and well-to-do woman. Only his servant has eyes to see what she herself, so deep is her need, cannot bear to acknowledge: her situation as a childless woman with an elderly husband.

And here, too, is the ostensible reason we read this story in tandem with the Torah reading of Vayera, which tells of Isaac’s birth: because, like Isaac’s mother Sarah, the Shunamite lady has been prophesied a son and doubts the prophecy. And there’s still more:

And the boy grew and one day

He went out to his father, to the reapers.

And he said to his father: “My head, my head,” and he said to his servant: “Take him to his mother.”

And he took him and brought him to his mother

And he stayed across her knees till noon and died.

Again like Sarah, the lady of Shunem has to face the possibility that her son will have been taken away by the very God who gave him. And yet, despite the enormity of her tragedy, this woman does not complain to God or cry out in pain, but reverts to her silence. Saying not a word, she “went up and laid him on the man of God’s bed and she closed the door on him and went out”—symbolically returning him to the prophet. The death, or her mourning, will not be public.

Then she called to her husband and said: “Send me one of the lads and one of the mules

And I’ll run to the man of God and be right back.”

But he said, “Why are you going to him today? It’s not the first of the month or Sabbath.”

And she said: “It’s fine.”

And she saddled the mule and told her lad: “Drive it and hurry and don’t stop me from riding

Unless I tell you.” And she went and she came to the man of God, to Mount Carmel.

And it was, when the man of God saw her from afar, he told Gehazi his lad,

“Look, there’s that Shunamite lady. Now run toward her and ask:

‘Are you well, is your husband well, your son well?’”

And she said [to Gehazi]: “It’s fine.”

In Hebrew, the question I’ve translated as “Are you well?” literally means “Is there peace with you?” Her answer, just like her answer to her husband’s query, is that same word: shalom, peace. She won’t say aloud what happened or why she needs Elisha. As with her need for a son, her loss of the son is beyond language.

That same silence envelops her as she herself runs straight to Elisha, throws herself down, and grabs onto his legs. When Gehazi, seeing this impertinence, tries to push her away, his master says, “Let her be. Her soul is bitter to her and the Lord kept it from me and never told me.” Once again, when it comes to this woman, his prophetic powers have failed him—almost as if God Himself has been echoing her silence. It’s only now that she speaks:

And she said, “Did I get a son from your worship on loan? Didn’t I tell you not to fool me?”

And he said to Gehazi, “Grab your things and take my staff in your hand and go.

If you come across a man don’t say hello and if a man says hello don’t answer,

But put my staff across the boy.”

Recognizing now what’s happened and why she grabbed his legs—just as she once grabbed hold of him, as it were, to make him eat her bread—he also realizes that her wordless gesture is meant to contain death by refusing to discuss it. Therefore, not a word of the death will be spoken between his learning of it and responding by putting his personal token—his staff—on the boy and raising him from death.

And Gehazi passed before them and put his staff across the boy but there was no sound and no stir.

And he went back toward him to tell him, saying: “The boy did not regain consciousness.”

Again, the story’s power comes from its silence. We don’t need to see Gehazi ride across the plains without saying a word, but we hear the silence in the room. The miracle hasn’t worked. So Elisha, who has followed, resorts to the direct method of personal, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Miraculously the boy warms, sneezes seven times (a masterful detail), and returns to life:

And the boy opened his eyes.

And he called Gehazi and said, “Call the Shunamite lady.”

And he called her and she came and he said: “Pick up your son.”

And she fell to his feet and she bowed to the ground and she picked up her son and left.

She cannot say a word.

The lady of Shunem is like all of us today—even when we’re not either wealthy or living on the brink of starvation—in that she is out of touch with her mortal needs. In contrast to Elijah’s widow woman, who understands that she’ll starve when the flour runs out and is willing to bet on the Lord and say thank-you when Elijah delivers, the lady of Shunem has suddenly had the mystery of existence opened before her and witnessed the true, uncanny omnipotence of the force that Elisha has called up. Words cannot convey either the abyss that opened beneath her feet or the depth of her gratitude.

There is only silence at the heart of this story: the silence of death and the silence of awe in response to the living presence of God. The lady of Shunem truly believes in God—she wants to honor His servant of her own accord—but when it comes to thanking Him she can only prostrate herself, grab her newly breathing son, and leave.

This is what makes the resurrection performed by Elisha, who has been given twice the spirit of Elijah, twice as great as the resurrection performed by his master: he has acquired the gift of eliciting true gratefulness and awe from someone unaccustomed to feeling a thing.

More about: Hebrew Bible, Religion & Holidays