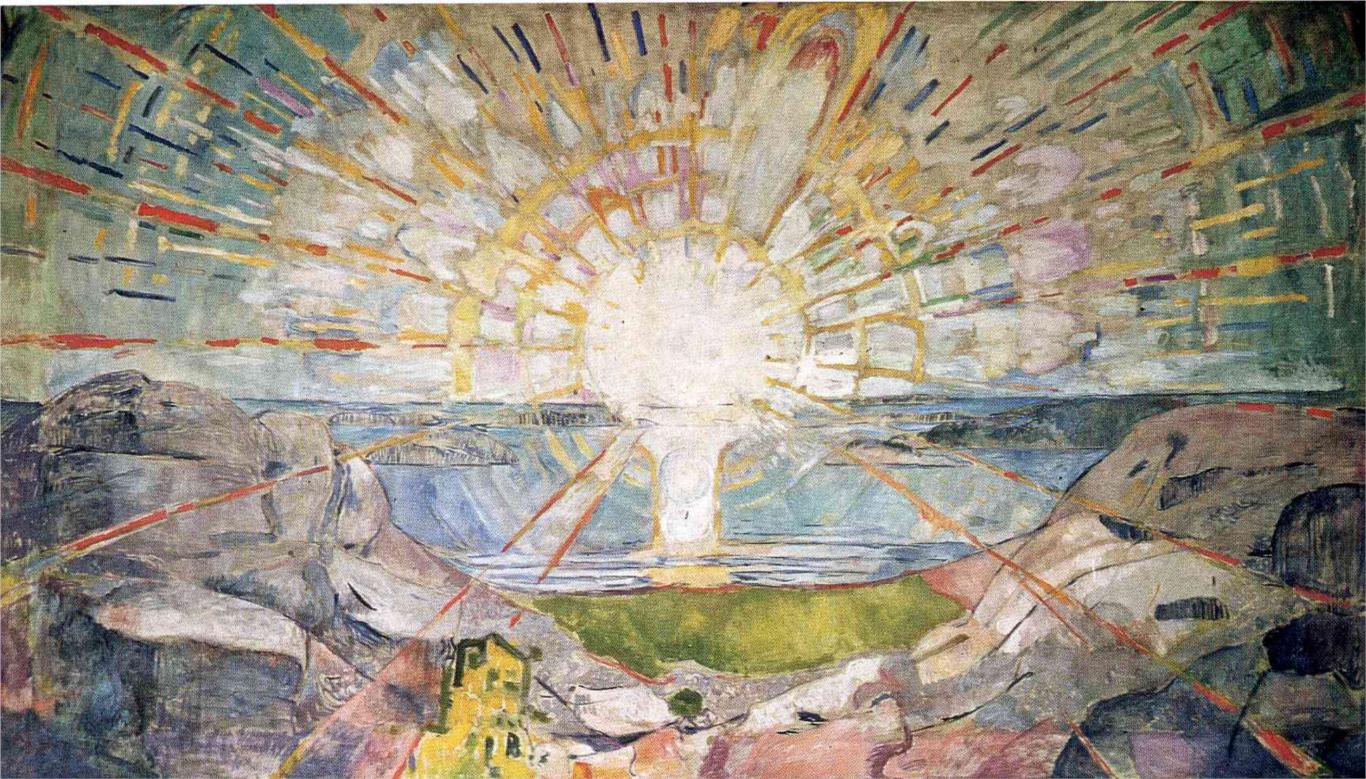

From The Sun by Edvard Munch, 1909. Wikipedia.

A centerpiece of the daily morning liturgy is the Sh’ma—the essential declaration of faith in the Almighty and His oneness. According to the Talmud, it must be preceded by two blessings, the second of which describes God’s love for the Jewish people. But the purpose of the first blessing, a much longer, lyrical paean to the sun and its rays, yoked to praises of the Creator sung by angels and seraphs and other elements of the “heavenly host”—is not nearly so obvious.

The Sh’ma’s two preliminary blessings come immediately after a substantial collection of songs of praise, many taken from the book of Psalms, that form a fitting preamble of their own to the Sh’ma’s quintessential statement of monotheism: “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one.” So why, just before getting to that statement, do the worshippers open with what could easily be mistaken as a hymn to the kind of celestial bodies frequently venerated not by God-fearing Jews but, to the contrary, by nature-adoring pagans?

As it happens, the construction of this prayer, and the contrasts it draws between those bodies and the One Who made them, point to the heart of Judaism and the values it seeks to instill in the unruly rabble who followed Moses out of the desert.

The contrast is drawn from the start in the prayer’s opening words, the words by which it is known: ha-Me’ir la-arets, “He Who lights the earth.” The origins of the prayer are shrouded in mystery, and its author is unknown, but it seems to date to Second Temple times. While the Mishnah (ca. 200 CE) refers obliquely to its existence, the actual text does not appear before the 8th century, and its exact phrasing was not agreed upon until a few hundred years afterward. As late as the 15th century there was debate over which parts of it could be recited by an individual praying alone and which were so holy as to be permitted only within a communal setting.

It begins thus:

He who shines over the earth and those who live upon it in His mercy

And in His goodness renews each day the act of Creation. . . .

The poet and philosopher Judah Halevi (1075-1141), in the Kuzari, his treatise defending Judaism against other faiths, asks why this passage does not refer to the One who in Genesis “made light and created darkness,” but is instead framed entirely in the present tense. His answer:

The business of Creation is not like the business of handicraft, because the craftsman, when he has made an anvil, for instance, goes on his way—and the anvil will do what it was made for. But the Creator, may He be blessed, creates limbs and gives them life and continually makes them function, minute by minute, and if . . . His attention and guidance should cease for one moment the whole world would be lost.

Which is to say, the prayer is not thanking Him for having created the stars, or the sun, or any particular celestial appurtenance. It is thanking Him for staying around and ensuring the job gets done, day after day. With this in mind, we can make sense of what follows:

How many are your works, Lord,

All of them you’ve cunningly crafted,

The earth is filled with Your possessions. . . .

God of the world, in Your great mercy

Have mercy on us, master of our energy,

Rock we run to, sheltering deliverer, our guardian.

Rabbi David Abudraham (circa 1340), one of the most influential commentators on the synagogue liturgy, explains the salience of the word “mercy” in this passage. It lies, he writes, in the fact that God

brings us the light in a merciful way, little by little and not all at once, since one rising from his bed, should he see a great light, would not be able to open his eyes in a hurry, but would instead have to stand for an hour like a blind man. . . . This, too, is testimony to the Lord’s continuing presence.

Echoing Halevi’s point about God’s continuing involvement in creation, Abudraham takes it a step farther by urging an appreciation of His extraordinary sensitivity in sparing humanity the jarring sensation of awaking suddenly to a painful glare. This observation may strike a reader as almost comical in its focus on so minor a detail, but there’s a theological point here: God hasn’t created the heavenly bodies to flaunt His powers but, in attending to human sensibilities, has imbued Creation with a moral dimension. It’s not there to make Him look good; it’s there to enable us to function.

What we have seen thus far adheres more or less to familiar aspects of the theme of God the Creator. But then the prayer takes an unexpected turn:

Blessed God Who’s great of thought,

Who prepared and formed the sun’s rays,

Well He made glory for His repute;

Lights He placed around His redoubt.

The stalwarts of His holy host,

Who extol the Almighty, always speak the praise

Of God and His holiness.

Suddenly, we’re no longer talking about the sun, moon, and stars as created objects but about sentient heavenly beings who can themselves praise God. If this is where the prayer appears to skirt most closely to paganism, the rabbis explain that these “stalwarts of His holy host” are angels, and relate their behavior to that of the unnamed man who wrestles all night with the patriarch Jacob only to excuse himself just before dawn (Genesis 32:25-31). According to the rabbis, that man is himself an angel, and must hastily depart precisely in order to praise God for bringing the daylight—just as do the angels described in ha-Me’ir la-arets, and just as Jews do in their prayers each morning:

May you be blessed Lord our God

In the heaven above and on the earth below

For all your praiseworthy handiwork

And for the illuminating lights you formed,

They themselves shall glorify you, Selah.

In extolling God “for the illuminating lights [He] formed,” which “themselves shall glorify [Him],” the prayer clarifies the hierarchical connection among these various elements. Unlike star-worshipping pagans, Jews praise not the great lights but Him who formed them, on the understanding that their merit comes from the fact that they, too, testify to His glory.

In fact, the nub of this whole prayer, according to Judah Halevi, is how puny those lights actually are. One who recites it, he writes, is meant not merely to reflect on “the greatness of the heavenly objects” but also to realize that those objects “are for their Creator like the tiniest of insects.” Otherwise, one might mistakenly come to believe that the sun, the stars, and the constellations “are helpful or harmful in and of themselves.”

And that is where the mighty host of angels and seraphs also come in. For one thing, they function as intermediaries, so to speak, between the created things and the Creator. But they also play a role specifically where humanity is concerned. For in exalting the social organization of the host of heaven, the prayer advocates some essential elements of an ideal social order on earth:

All are beloved, all are selected, all mighty, all holy . . .

And all accept upon themselves the rule of heaven

One to the other, and lovingly permit one another

To sanctify their creator with an easy spirit

With a clear tongue and sacred harmony;

All as one respond in awe and say:

Holy Holy Holy!

Why does the prayer invoke specifically the angels’ politeness with each other? The minor talmudic tractate Avot d’Rabbi Natan elaborates: whenever an angel is about to recite a song, he first turns to his fellow and says, “You start, because you’re greater than I am”—as opposed to mortals who, the text comments, are always eager to say, “I’m greater than you.” In other words, the angels behave the way they do on high in order to encourage us to behave likewise down below.

Ultimately, the difference between a sun-worshipper and a Jew is what each sees in the sky. The former looks at the sun and is led to believe it is the most important thing of all. The Jew looking at the sun not only remembers that the miracle of Creation has been repeated, yet again, by a God who is ever present and ever concerned with humanity, but is also driven to reflect on the angels whom he cannot see but from whose ethical conduct, it is hoped, he can learn.

And that is what the prayer Ha-me’ir la-arets is doing here. The blessing of thanksgiving that immediately follows it and leads into the Sh’ma speaks of God’s love for the Jewish people: He taught us the Torah, gave us His laws, and will one day bring the redemption. Those gifts are particular to this people, but also somewhat abstract. The preceding blessing of Ha-meir la-arets gives to the person who recites it something that is not only universal but highly personal—something he or she can relate to physically: the slowly breaking dawn, the moon’s regular waxing and waning, the stars that light up the night. Even when talking of angels and other ethereal creatures, Ha-me’ir la-arets provides touchingly instructive details that humanize and moralize them.

Before getting to God’s love for the Jews, and the emphatic declaration of faith in Him that is the Sh’ma, the rabbis wanted God’s chosen people to stop and think about the connection between one individual and another in a world where nothing is devoid of moral consequence. Only then, without just referring to the manufacturer of the heavens, can they proclaim, “the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.”