Every year, the Torah portion of B’midbar (“In the Desert”)—the first reading in the biblical book known in English as Numbers—coincides roughly with the festival of Shavuot (“Weeks”), celebrated this year on next Sunday and (in the diaspora) Monday, and traditionally referred to as “the time of the giving of our Torah.”

The background, recounted in the book of Exodus, is this: seven weeks after leaving Egypt, the Israelites receive, at Sinai, not only the Torah but also the awesome revelation of God’s presence. Now, in Numbers, that transcendent moment of closeness with God has been extended into history as a living presence in the divinely-ordained Tabernacle, just as it will eventually become a living presence in the Temple in Jerusalem and, ultimately, in every space in which Jews gather to pray.

How much space, exactly, need be dedicated to this purpose? As little as arba amot—four cubits—will suffice, a cubit being equal to the span from one’s elbow to the tip of the middle finger, and four square cubits being roughly equivalent to six square feet. And here’s the rub: no single person’s cubit is identical in dimensions to another’s. Everyone makes—everyone is commanded to make—his or her own space for God.

But how to depict that God-space? Christianity approached this problem by making the space human, tailored to the physical dimensions of one particular 1st-century Jewish craftsman from the Upper Galilee. Jews adopted a different approach, dictated by the requirement to shun altogether any depiction of the divinity. True, in art there have been outlying exceptions to this rule, mainly in occasional anthropomorphic images of God produced by Christian artists working for Jews; but they are just that: exceptions.

By contrast, for a quintessentially Jewish approach to the problem, we can look to one of the loveliest and most refined of medieval manuscripts made for Jews. The manuscript is known, rather cumbersomely, as the Duke of Sussex German Pentateuch. Illuminated around 1300 in the Lake Constance region of Germany, and now housed in the British Library, it contains, as its name suggests, the Five Books of Moses, each with its own beautiful title page.

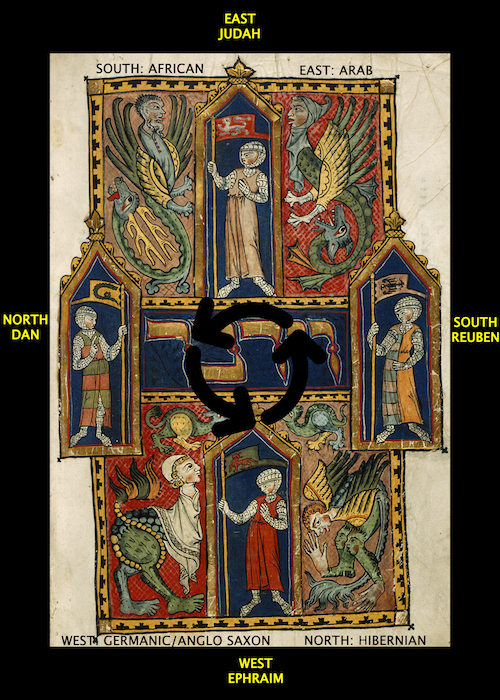

It’s the title page of Numbers that concerns us here. [Fig. 1] .We are confronted by four knights, each of whom holds a banner decorated with an animal symbol. The knights, elegantly posed around the four sides of a panel of text, are meant to evoke the four leading Israelite tribes—Judah, Reuben, Ephraim, and Dan—arranged around the mishkan, that is, the desert Tabernacle of the divine presence.

In both Jewish and Christian art, the desert Tabernacle is always represented as an architectural structure. Yet here it is signified simply by the frame of the text panel. Inside that frame, moreover, one sees none of the accustomed accouterments of the Tabernacle—neither the lampstand nor the showbread table, the dividing curtain, or the Ark. Instead, we have the single, opening word of the book: va-y’dabber, “And He Spoke.”

But that word is not just any word: the “He” denoted by the verb form is Y-H-V-H, the never-to-be-pronounced name of God that, in the biblical text, immediately follows the opening word. Which is to say: va-y’dabber represents not only God’s speech but His very presence.

This is an image compelling in its uniqueness, its conceptual brilliance, and its visual majesty. Created in a workshop run by Christians, it appears in an illuminated manuscript that was clearly planned, designed, and commissioned by learned Jewish patrons.

Let’s now move to the figures on the page. Each of the four Israelite tribal leaders positioned protectively around the central image is portrayed in the grip of one or another emotion, but it is not easy to say what that emotion might be. Is Judah angry, Reuben positive, Ephraim calm, and Dan depressed? Or are we intended to read into their faces some other range of sentiments? [Fig. 2].

Any answer to that question cannot be straightforward, for the images of the Israelite tribal leaders are hardly intended to be literal depictions of their human personalities. In Scripture as well as in later rabbinic literature and biblical commentaries, both exoteric and esoteric, the Israelite tribal leaders are portrayed as meta-human epitomes of particular, and particularly noble, qualities. In the Duke of Sussex Pentateuch, the leaders’ facial expressions can be read as distilling four distinctive human types, perhaps corresponding to the four classical humors or temperaments—in order, choleric (Judah), sanguine (Reuben), melancholic (Ephraim), phlegmatic (Dan). [Fig. 3] In that sense, their facial “masks” function like the masks of Comedy and Tragedy on the marquee or proscenium arch of a theater.

Thus, the figures are at once broadly human and perhaps not entirely human. There are four of them, at the four points of the compass. Although they represent specific, abstract qualities of human character, as part of a traditional symbolic diagram they can be read on both the earthly/historical level and on the cosmic plane, correlated not only with their specific position on the compass but perhaps even with specific abstract qualities within the divinity.

The knightly Israelites, however, are not the only figures on the page. They share it with four gigantic, lurid, menacing creatures with human faces and animal bodies.

Who are these grotesque hybrid monsters? The fact that they are positioned in a threatening manner around the stalwart Israelite knights suggests that they evoke the trials and tribulations that beset the Israelites in their desert wanderings. Some of those tribulations consisted of inanimate obstacles (like rocks, cliffs, or howling wilderness), elemental forces (wind, heat) or natural predators (snakes, scorpions)—none of which seems to fit the case here. Nor, since there are only four creatures, can they be easily taken to represent the “seven nations greater and mightier” than Israel whom, according to Deuteronomy (7:1), the Israelites will rout after entering the Promised Land.

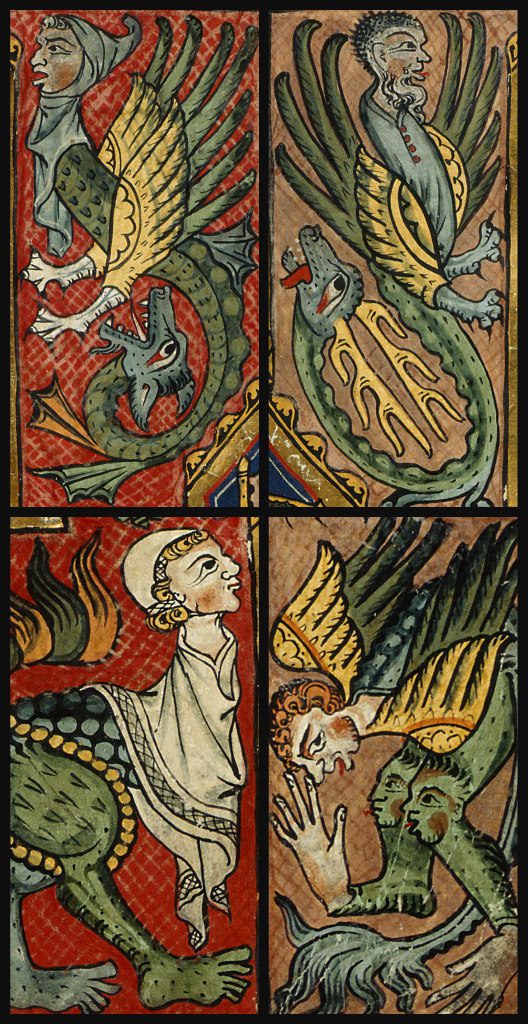

Let’s set aside the distorted bodies and concentrate on the faces. Like the Israelites, these creatures are undoubtedly individuals, while also, like the Israelites, “masked.” Their masks, however, are not those of universal humors or temperaments but of four ethnic types corresponding geographically to the four cardinal points of the compass. They are: on the top left, a Persian or Arab [Fig. 4]; on the top right, a conventionally African figure [Fig. 5]; on the lower left, an English or Germanic type [Fig. 6]; on the lower right, a Hibernian type whose knees are fronted by two additional human heads with puffed-out cheeks, perhaps representing the (northern) winds [Fig. 7].

Although none of the monsters’ human faces is grotesquely caricatured, they appear at once disorderly and disrespectful. The Hibernian type on the lower right is particularly so, bending over to show its rear end and making a rude nose-thumbing gesture with one of its hand-feet. The English or Germanic type on the lower left is the only one of the four that is not sticking out a pointed tongue.

Despite appearing to have been randomly thrown together, the four have their own internal logic. The fact that they are four in number and associated with the cardinal directions suggests that, like the Israelite knights, they represent a totality of some quality. In their case, that quality is, in one word, non-Jewishness.

These monsters represent “the goyim” who, in their distinct ethnic otherness, threaten and terrorize the pure and inviolate Jewish people. The latter, for their part, stand unbowed and unafraid within their small golden niches lined with red, safe in the knowledge, duly recorded in Deuteronomy (8:15), that God “led you through that great and terrible wilderness in which there were venomous serpents.”

What do we have here? In the depicted “reality” of the Israelite tribal setting, the monsters cannot harm the Israelites. But, in the milieu of 14th-century Ashkenaz, might the images of the monsters be meant to reflect negatively upon the contemporary Gentiles?

In art, these disparaging images are, in fact, mirror images of denigrating images of Jews made for consumption by Christians. They thus represent an unusual instance of Jews re-purposing an iconography that has been used against them. One telltale difference is that Jews were often pictured with normal human bodies and monstrous faces. Here, the Gentile figures have “normal” (though ethnically identifiable) faces but distorted, monstrous bodies.

This adjustment was no doubt artistically necessary, so as to make clear the reverse-stereotyping of the enterprise as a whole while also pointing out visually the fact that anti-Jewish hostility manifests itself in a variety of forms, in all “four corners of the earth.” But the overall result is the same: in our illumination, anti-Jewish caricature has been appropriated and reformulated as anti-Gentile caricature, with the Jews now portrayed as personifications of ideal human archetypes.

But lest we suppose that the Jews making this visual statement lived, somehow, in a parochial enclave completely separate and shut off from the wider culture, another look at the image allows us to discern something about the real cultural situation of the Jews who commissioned and designed this Bible.

Consider the configuration of the two sets of images—that is, the direction in which one must read each set, Jewish and non-Jewish, in order to make sense of it. In the cartographic convention of the 14th century, the top of the map was always East (not North), with the remaining compass points ordered as North (right), West (bottom), and South (left).

Now start with the diagram of the Tabernacle, where the tribal leaders are identified by the flags they bear. Top is East (Judah). Next, reading counterclockwise in the “Hebrew” direction, we have, as expected, North (Dan, left), West (Ephraim, bottom), and South (Reuven, right) [Fig. 8].

Now proceed to the Gentile monsters, reading them in the same direction. Starting again from East (Arab/Persian, top right), we have South (African, top left), West (Western European, bottom left), and North (Hibernian, bottom right). But this is a mess: by cartographic convention we should have East, North, West, South. The solution: the images of the Gentile monsters should be read not in the “Hebrew” but expressly in the “Latin” (clockwise) direction, yielding East, North, West, South just as for the tribal leaders. [Fig. 9].

The difference vividly demonstrates the manuscript’s acute sensitivity to the distinctive priorities of its patrons and designers. And it also divulges a clue as to the kind of people those patrons were: namely, people inhabiting—however incompletely, or occasionally uncomfortably— several worlds at once.

We see this in the very fact that the patrons sought out Christian artisans and, with them, planned an object that, in a deeply Jewish manner, ranks with the very best products of those artisans’ workshops. And in that product we see something more: a tour de force of cross-cultural collaboration.

Space is the universal human patrimony. But while all humans inhabit the world, they may think about it in different ways. The Jews who planned, designed, and commissioned this manuscript lived in two worlds. They were Jews and, simultaneously, early-14th-century inhabitants of German lands. Out of this combined reality, they created a product responding to both aspects, just as the diagram they created responded to two sets of directionalities. If we try to read their product from only one of the two perspectives, we will always come up short. Each mode—each identity—is ineluctably, inextricably intertwined in the other.

Which brings us back to the four cubits that suffice to create a prayer space expansive enough to contain that which is infinite and transcendent but, simultaneously, bounded enough to be a fitting vessel for transcendence.

This inner space must be protected from the distractions that besiege human life, but not so guarded as to admit nothing from outside. It must “read” equally viably from the particular Jewish perspective and from the wider perspective of Jews as humans in the world: two elements that should, ideally, be not disjunctive but integrated and contiguous.

On Shavuot, the time of the giving of the Torah, heaven touched earth. On a glorious 14th-century title page of B’midbar, a mechanism is introduced for re-experiencing that moment anywhere and anytime Jews gather to pray.

More about: German Jewry, Middle Ages, Religion & Holidays