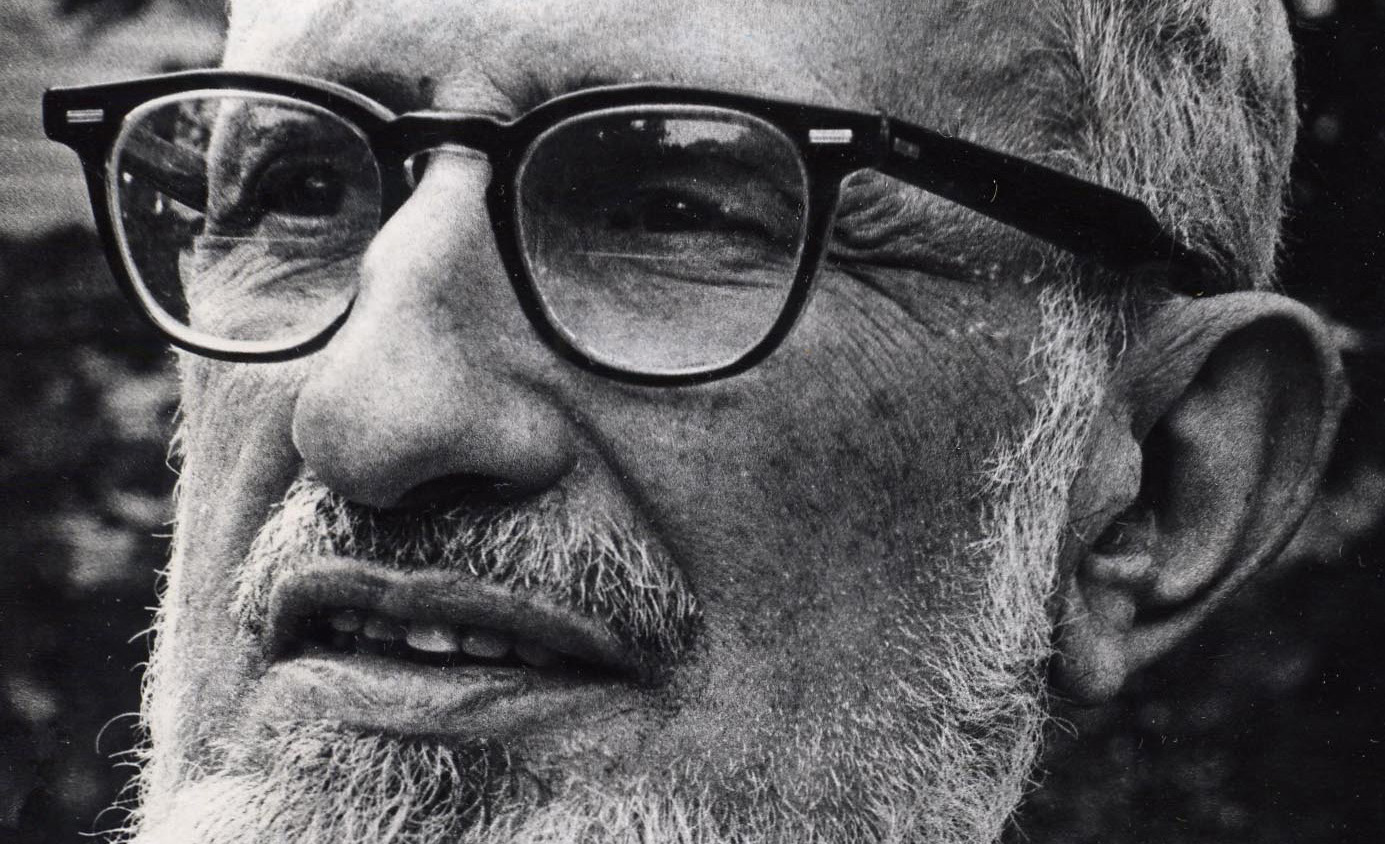

To those knowledgeable in the history of Jewish-Christian relations, the name “Soloveitchik” immediately brings to mind a complex, challenging, and subtle essay by Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903–93), the most influential figure in Modern Orthodoxy to date.

Published in 1964, when interfaith dialogue was rapidly becoming common (and Vatican II was in session), Soloveitchik’s essay, “Confrontation,” sought to delineate the boundary marking off the domain in which committed Jews and Christians could and should work together from the domain in which even intelligible communication between them was conceptually impossible. Jews, Soloveitchik wrote, “are determined to participate in every civic, scientific, and political enterprise,” but Jewish identity and Jewish obligations could not be exhausted by, and were actually misapprehended by the terms of, such universal ethical and cultural concerns.

Nor was this stricture peculiar to Judaism alone. Quite the contrary, Soloveitchik argued: “[t]here is no identity without uniqueness.” Just as “there cannot be an equation between two individuals, . . . it is likewise absurd to speak of the commensurability of two faith communities that are individual entities.” Once those entities were subsumed into some larger unit, with the differences between them relegated to a minor matter, their “dialogue” could only be false—and, what is more, dangerous to the participating groups:

Standardization of practices, equalization of dogmatic certitudes, and the waiving of eschatological claims spell the end of the vibrant and great faith experience of any religious community.

To this acute analysis one might add that, since the standardizing moves against which Soloveitchik warned were more likely to reflect the thinking of the larger community, they posed a commensurately greater danger to the smaller one. As if to reinforce that point, an appendix to the original publication of Soloveitchik’s essay included a statement by the (Modern Orthodox) Rabbinical Council of America rejecting even more firmly “any suggestion that the historical and meta-historical worth of a faith community be viewed against the backdrop of another faith, [or] the mere hint that a revision of basic historic attitudes is anticipated.”

But here is something strange: this entire line of reasoning on the subject of interfaith dialogue is the reverse of the view articulated by another and much earlier Rabbi Soloveitchik. That earlier Soloveitchik, Elijah Zvi by name (1805–81), was the brother of Joseph’s great-great-grandfather. Also, as it turns out, he was the great-great-great-grandfather of the current president of Yale University, Peter Salovey.

Writing in the wake of Yale’s announcement of its new president in 2012, Shaul Magid, a professor of Jewish studies and religion at Indiana University, drew attention to Salovey’s illustrious forebear in an article in Tablet provocatively titled “The Soloveitchik Who Loved Jesus.” There, Magid located a reason for Elijah Zvi’s relative obscurity: it lay in “his love of Jesus Christ,” a love that drove him to write “a commentary to parts of the New Testament (Mark and Matthew) and a book [that] argues for the symmetry between Judaism and Christianity and claims that there is nothing in Christianity that is alien to Judaism.”

Now the book on the gospels has at last come out in English, translated by Jordan Gayle Levy and edited with a helpful introduction and commentary by Magid and a preface by none other than Yale’s president. In that preface, Salovey (whose name, he tells us, reflects his grandfather’s “desire to preserve ‘love’” in Soloveitchik) finds the work of his great-great-great-grandfather greatly relevant to the present moment: “he models for my generation of the family the significance of independent thinking (even in the context of religious orthodoxy) and the importance of seeking to understand the ‘other.’”

It cannot be gainsaid that Rabbi Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik, apparently to the end of his life a fully observant (not to mention highly learned) Jew in the Lithuanian mode, demonstrated a startling degree of independence of thinking. But whether he also really sought to understand the “other” is much to be doubted. And so is the claim of Magid that he “seemed to fall in love with Christianity.”

II

Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s Hebrew book treated only Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the three closely related gospels that are known as the “synoptics.” (In an unfortunate slip, the translator writes of “all four of the synoptic Gospels.”) The commentary on Luke seems to be lost, as does the original of the commentary on Mark, which survived only in French; the current English version has been prepared from that copy. In general, Levy’s translations of the commentaries on both Matthew and Mark are clear, although not without some mistakes. The translations of the gospels themselves, however, are deeply problematic.

Consider the first beatitude in the Sermon on Mount, usually translated as “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3). Levy renders this as “O, the gladness of the poor in spirit,” and uses the same awkward wording for the other beatitudes as well. But the opening phrase in Soloveitchik’s own Hebrew translation (’ashrey ha‘aniyim ba-ruaḥ) employs a common biblical word that means “blessed” or “happy,” as in Psalm 84:5, prominent in the Jewish liturgy: “Happy (’ashrey) are those who dwell in Your House; they forever praise You” (JPS Tanakh). Why not do likewise with the translation in Soloveitchik’s commentary?

The answer lies in the editor’s and translator’s initially reasonable conjecture that the Hebrew translation in Soloveitchik’s commentary derived from the work of Franz Delitzsch (1813–90), a Christian scholar outstanding for his Hebraic and Judaic learning. Less reasonable is Levy’s decision to use “an English New Testament edition directly based on Delitzsch’s scholarship,” published in 2011 by Vine of David Press, a Christian missionary organization whose translators are quite open about their method: “We have translated idioms rigidly.”

Indeed they have, and the clumsy “O, the gladness” is a good example. It is from the same translation that Levy uses for the name of Matthew—“Mattai”—which reflects Delitzsch’s Hebrew but not Soloveitchik’s; the latter uses “Matya.” Delitzsch surely found “Mattai” in an anti-Christian passage sometimes censored from editions of the Talmud and not, so far as I can see, referred to in Soloveitchik’s commentary. The latter’s use of “Matya,” a name well attested in the Talmud, should surely have carried over into the current English translation.

This difference in names is small but significant. Nor is it the only example of differences between Delitzsch’s translation and the version in Soloveitchik’s commentary that turned up in my spot-checking. Whatever the actual historical relationship may have been between the two Hebrew translations, the decision to substitute Delitzsch’s work for Soloveitchik’s Hebrew, and in a clumsy rendering into English at that, is regrettable.

Also worrisome is the creation in the translation of a new biblical figure, “Doeg the Armenian.” In Soloveitchik’s comment on Matthew 15:32, the Hebrew is actually “Doeg the Aramean” (dw’g h’rmy). But the latter word was surely a typographical error for the orthographically almost identical term h’dmy, “the Edomite”: the identification of Doeg’s ethnic group that accompanies his name in all five verses in the Hebrew Bible in which he appears. He is never an Aramean, still less an Armenian.

For his part, Shaul Magid in his introduction and commentary does a fine job of attempting to place Soloveitchik among other contemporary scholars of nascent Christianity, a field rapidly developing when he wrote his book in the mid-19th century. The task is a difficult one because we have no clear evidence that Soloveitchik had any awareness of the important work in this area taking place in Western academic institutions. One might reasonably suspect that he was responding to learned Christian missionaries (some of them of Jewish origin) who explored the relationship of Jesus to the Judaism of his time for their own purposes; but hard evidence is still missing.

Magid also discusses Soloveitchik’s work in comparison with contemporary Jewish reformers, some of whom were quite involved in the developing question of Christian origins. “For most of them,” he writes,

their positive appraisals of Jesus was [sic] also a veiled (and sometimes not-so-veiled) critique of Christianity while using their “Jewish Jesus” as part of their case for emancipation and the inclusion of Jews into European (Christian) society.

For these reformers, in other words, Jesus was good; he practiced Judaism. Christianity, “the religion about him,” was something else.

Ironically, however, Soloveitchik, the East European Orthodox rabbi, stood in a sense to the left even of these liberal reformers. His goal, at least in his own mind, was, as he put it in his dedication,

to reconcile these two enemy sisters: the Church and the Synagogue. I wanted to prove that this centuries-old enmity was based on dreadful misunderstandings through false interpretations by everyone—Jews and Christians—that were made concerning the words of Yeshua [i.e., Jesus] and the Apostles, who tried to instill in humanity the love of ONE GOD and the love of one’s NEIGHBOR.

To this very modern-sounding manifesto, Magid provides an instructive contemporary contrast in the thinking of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin, a major figure in the Lithuanian talmudic establishment (and whose granddaughter, incidentally, married a Soloveitchik). On the basis of “the midrashic principle of ‘Esau hates Jacob’”—that is, the principle that the Roman world and later the Christian world inevitably despise the Jews—Berlin argued, in Magid’s words, “that anti-Semitism was somehow embedded in Christianity, or Gentiles more generally, such that it could not be uprooted.” By contrast, Soloveitchik’s commentary on the synoptic gospels represented a determined effort precisely to uproot this hoary and, to his mind, deeply misguided notion.

But what about that commentary itself? Is it indeed as “modern” as the tone and thrust of the dedication clearly imply, or does the word “modern” require qualification?

Magid calls Soloveitchik “the first modern Jew to write an actual commentary on the New Testament.” Chronologically, the term “modern” here is accurate enough: the man lived through most of the 19th century. Culturally, however, and despite his untraditional views of Christianity, he, too, was thoroughly embedded in the world of East European talmudic learning in the Lithuanian (and non-ḥasidic) mode. Moreover, he gave no sign of awareness of the revolution in the historical interpretation of authoritative religious literature that had been gathering steam in the West for about two centuries by the time he wrote. He thus took all of the stories in the gospels to be historical and, when accounts contradict one another, rather than seeking to delineate a sequence of development in pursuit of an accurate reconstruction, he simply tried to harmonize the discrepancies.

Consider, for example, the contradictory accounts of Jesus’ alleged prohibition on divorce in Mark and Matthew. The former reads: “One who sends away his wife and takes another is an adulterer against her” (Mark 10:11); the latter reads: “One who sends away his wife other than for a matter of promiscuity brings her into the grasp of adulteries, and he who takes the divorced woman as a wife is an adulterer” (Matthew 5:32). (“Grasp of adulteries” is an over-literal rendering of Delitzsch’s Hebrew and fails to reflect the wording in Soloveitchik, which means simply “causes her to commit adultery.”)

So did Jesus permit a man to divorce his promiscuous wife or not?

To a scholar working in the distinctively modern, or historical-critical, mode of interpretation, the discrepancy might elicit an observation about the different schools of thought represented in the two gospels or about their relative chronology. (It is now widely believed that Matthew used and adapted Mark.) But Soloveitchik approached the discrepancy like the traditional talmudist he was and sought merely to interpret it out of existence. “Yeshua’s thought is not completely expressed here,” he wrote of the version in Mark. “In the Gospel of Mattai, it is more explicit; for in two locations (5:32 and 19:9), he authorizes divorce in the case of promiscuity (or adultery).” With this, Soloveitchik forwent any chance to gain knowledge about the range of opinion on divorce in early Christianity or in the subsequent history of the Church, or about the literary relationship of the gospels to each other.

So focused was Soloveitchik on textual harmonization that, as Magid puts it, he “does not view Judaism and Christianity as categorically distinct.” Nor, unlike some of his liberal Western contemporaries, did he “view Jesus as a ‘reformer’ or even a rabbinic rebel but rather [as] a normative teacher of the Mosaic message”—essentially, a figure from Soloveitchik’s own culture.

Still, some nuancing is in order when Magid also observes that “Soloveitchik never claimed to be objective.” It is not that, in the manner of what Christians sometimes call “constructive theology,” he forswore objectivity in favor of a self-consciously confessional or normative statement. Rather, the whole category of objective analysis, independent of the interpreter’s own commitments (so far as this is possible), was unknown to him. If we insist on invoking the word “objective” at all in Soloveitchik’s case, we would have to say that his ahistorical, harmonistic, exclusively rabbinic interpretation of Jesus and the synoptics was for him the sole—and thus the objective—truth. (Admittedly, he occasionally identified Jesus as an Essene—a term nearly as opaque then as now—but the implications of this did not much affect his actual interpretations of Jesus’ teaching.)

Today, scholars of late Second Temple Judaism and of Christian origins benefit from a large corpus of texts—principally the Dead Sea Scrolls and other discoveries from ancient Judea—that were unknown in Soloveitchik’s time. One striking effect of the new data has been to enhance scholars’ awareness of the internal diversity of Judaism itself at that time, and in this light to contextualize the rabbinic sources, most of which come from centuries later, accordingly.

One can hardly fault Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik for failing to take account of today’s vastly expanded information. Still, even before the new discoveries, as a book like Albert Schweitzer’s famous The Quest of the Historical Jesus (1906) shows, it was already possible to place Jesus and nascent Christianity in a Jewish framework very different from that of the rabbis. This was the framework of acute eschatological expectation, abundantly attested in the Jewish apocalyptic literature of the time. In sharp contrast, Soloveitchik consistently denied this dimension, going so far as to insist over and over again—and at great expense to his credibility—that Jesus made no messianic claims.

For instance, when Jesus instructs his disciples to announce that “the Kingdom of Heaven is on the brink of arrival” (Matthew 10:7), Soloveitchik simply identified this famous proclamation as “the main principle that he commanded to his disciples first of all, to allow the faith in the unity of the Creator to be instilled in their hearts.” When two disciples of John the Baptist ask Jesus, “Are you the one who comes, or should we wait for another?” (Matthew 11:3), Soloveitchik paraphrased this as, simply, “Are you the man who has already come, or no?”—a gloss that, as Magid notes, “does not cohere with Jesus’ response, which seems to imply a messianic unfolding.” When Peter confesses to Jesus, “You are the mashiaḥ, the son of the living God!” (Matthew 16:16), “Peter meant,” according to Soloveitchik, “that Yeshua was worthy to be messiah because of his great righteousness, and he was even worthy to be called son of God.”

Elsewhere, Soloveitchik identified “the messiah” with “one who will be as the rabbi and teacher,” again preferring notions of rabbinic authority to the intense apocalypticism of the gospel. And at one point, exhibiting considerable exegetical agility (but not equivalent respect for the plain sense), Soloveitchik had Jesus explicitly denying that he is the messiah. “For many will come in my name, saying, ‘I am the mashiaḥ,’ and they will mislead many,” reads Matthew 24:5. The gloss? “Yeshua told them that many would come in his name claiming that he [emphasis added] was the messiah, and by this they will mislead many.”

At the time of Jesus and early Christianity, another key aspect of much Jewish eschatological expectation was the resurrection of the dead—God’s miraculous end-time intervention to raise the deceased from the dust, bringing them back to life as fully embodied human beings (not disembodied spirits). This formed the background of the New Testament focus on the reports that Jesus, in what was seen as a token of the rapidly approaching consummation, had already risen from the dead. Here, too, Soloveitchik consistently evaded the inconvenient implication, mostly by conflating the resurrection of the dead with a different notion, the immortality of the soul.

Thus, commenting on Mark 8:31, in which Jesus predicts that “he would be killed, but at the end of three days he would surely rise,” Soloveitchik informed his readers that “[h]e did not mean he would actually resurrect [sic] physically, but that he would reappear in order to convince them, by this act, of the principle of the immortality of the soul.” Here, the influence was less the Talmud—the rabbis made the resurrection of the dead a key defining doctrine, to be reiterated in the liturgy every day—than the medieval philosopher Maimonides, who, as Magid notes, “elid[ed] resurrection with the immortality of the soul.” In this instance, the effect was not only to remove Jesus from an apocalyptic framework but also to deny a key Christian claim for his uniqueness.

All of this suggests a qualification of a point made by Magid when speaking in Tablet of Soloveitchik’s “love of Jesus Christ.” As is well known, “Christ” is the Greek word for “messiah.” To the extent that Soloveitchik denied that Jesus was the messiah, he was not dealing with what Christians have traditionally meant by “Jesus Christ” or, for that matter, with what the New Testament means by it. Nor was he speaking, as Christians historically have done, of Jesus as the crucified and risen messiah, God’s only begotten son, who gave his life in ransom for the sins of humankind.

Rather, the Jesus Soloveitchik loved, and wanted Christians to confess, was largely a figure of his own creation and in his own image: a talmudically learned sage whose teaching and practice adhered faithfully to rabbinic law and theology.

Magid wonders how Soloveitchik would answer a Jew who said, “‘If both [Judaism and Christianity] are true, I will convert for the sake of convenience because my lot in this world will be better by living as a Christian.’” The question is a good one but was unlikely to be asked, since what Soloveitchik wanted Christianity to be was quite different from what it had traditionally been and what it is for nearly all Christians today as well. In this, he proved, in fact, to be less distant than might at first seem from those Western reformers of Judaism whose “positive appraisals of Jesus,” in Magid’s words, were “also a veiled (and sometimes not-so-veiled) critique of Christianity.”

For Soloveitchik’s highly positive view of Jesus was, whether he fully realized it or not, also a blow at the heart of Christianity, requiring its adherents to make changes great and small—as small as no longer substituting Sunday for Saturday as the Sabbath and as great as dropping the identification of Jesus as the messiah and risen from the dead. By contrast, he called upon the Jews to make much more minimal changes, such as accepting his claim that the ostensibly anti-Jesus passages in the Talmud are about a different figure and abandoning the belief that Christianity was ineradicably anti-Semitic.

In brief, he seemed to want the Jews to be Orthodox but the Christians to transform themselves into something more like philo-Semitic Unitarians.

III

This brings us back to Rabbi Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik great-great-grandnephew Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and his powerful 1964 essay, “Confrontation.” The latter, it will be recalled, argues that identities are irreducibly particular; they cannot be converted into abstractions or exhaustively subordinated to larger sets of affiliation. Applied to religious groups, this means that “standardization of practices, equalization of dogmatic certitudes, and the waiving of eschatological claims spell the end of the vibrant and great faith experience of any religious community.”

Whether Elijah Zvi’s program entailed a full-fledged “standardization of practices” for Jews and Christians is open to doubt: he did insist that Jesus sought to uphold the Torah of Moses but never, so far as I can see, that Christians ought to observe the whole complement of its commandments. On the other hand, the “equalization of dogmatic certitudes and the waiving of eschatological claims” would seem to be a very appropriate characterization of what Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik sought to bring about through his commentary on the synoptic gospels. And the result of that enterprise offers a good illustration of precisely the dangers against which the later Soloveitchik would warn.

To be sure, an exploration of the commonalities between the New Testament and its Jewish parallels can indeed be useful in bringing about the good relations between Christians and Jews for which Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik longed. Similarly, the rabbinic parallels adduced by him can indeed still enlighten members of either group who underestimate the Jewishness of Jesus and of the gospels in general. Such parallels can also serve (and perhaps were intended to serve) as powerful antidotes to the disparagement of the Talmud in which many Christian intellectuals, including missionaries to the Jews, have engaged, as some still do.

Interestingly, too, although readers of “Confrontation” have not always noticed it, the more recent Soloveitchik himself saw some value in what he called “a common tradition uniting two faith communities such as the Christian and the Judaic.” “This term,” he wrote,

may have relevance if one looks upon a faith community under an historico-cultural aspect and interprets its relationship to another faith community in sociological, human, categories describing the unfolding of the creative consciousness of man.

In my own view, the honest encounter with another community can have both religiously and socially positive results. It is shortsighted to oppose all theologically focused dialogue, or to imagine that the result can only be the loss of religious authenticity. The rub, rather, comes when historians’ findings are given normative theological meaning, displacing the particularities of one or both traditions and eliminating those points of conflict between them that are not owing to mere misunderstanding or prejudice (as some are). In Jewish-Christian dialogue, the temptation to present the two traditions as “two peas in a single religious pod,” as I’ve put it elsewhere, is powerful and seemingly unending. For reasons of both historical accuracy and theological fidelity, it must be stalwartly resisted.

But this, finally, leads to us to reassess the appreciation of Rabbi Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s commentary by his great-great-great-grandson, President Peter Salovey of Yale University. Here again is Salovey’s tribute to his forebear in the preface to this book:

He models for my generation of the family the significance of independent thinking (even in the context of religious orthodoxy), and the importance of seeking to understand the “other.”

That Salovey’s ancestor demonstrated striking independence of thought and in the process proved to be a fascinating figure in cultural history is beyond doubt. But did he really seek to understand the “other”? The evidence suggests, rather, that he sought to efface the otherness of Jesus and the gospels by subsuming them into the world of talmudic Judaism as he understood it. That being so, Rabbi Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik was neither the first nor the last person to imagine himself open to outsiders while actually insisting that they think like insiders.

More about: Jewish-Catholic relations, Jewish-Christian relations, Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Religion & Holidays