Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, who died last week at the age of eighty-three, was a towering figure in the field of Jewish learning, with some 60 books to his credit in such diverse areas as Talmud, Kabbalah, and Jewish philosophy—an all the more astonishing output when one considers that he had no Jewish education to speak of until he was a teenager. Yet of all his contributions, the one having the greatest impact is not a book he authored. It is his translation into pure Hebrew of the entire Babylonian Talmud, a huge work of dozens of volumes written in a mixture of Hebrew and Aramaic, the now nearly extinct language spoken by the Middle East’s Jews in the Talmudic period.

Although Aramaic is a Semitic language closely related to Hebrew (one might compare the distance between them to that between Italian and Spanish), it is not for the most part intelligible to the Hebrew reader untrained in it. Hebrew, too, of course, was far from universally understood by Jews over the ages, yet a familiarity with the Bible and the prayer book gave many Jews a basic knowledge of it that enabled them to grapple with such all-Hebrew texts as the Mishnah, the Talmud’s first, shorter, and simpler part. The Talmud’s second and far lengthier part, however, the Gemara, with its large Aramaic component mixed with Hebrew, remained a sealed work for all lacking a rabbinic education.

The Steinsaltz Talmud, therefore, which has been retranslated since its publication into other languages, including English, has been truly revolutionary in its opening up of the Gemara to the ordinary Jew, both in Israel and the Diaspora. And yet one needs to be aware not only that it is, like all translations of great works, a mere approximation of the original, but that it is even more of an approximation than other works, because it cannot in itself convey the Gemara’s unique bilinguality. Translated into pure Hebrew, let alone English, from its Hebrew-Aramaic mélange, it loses the atmosphere of switching back and forth between the two languages that is typical not just of talmudic discourse but of Jewish life throughout history.

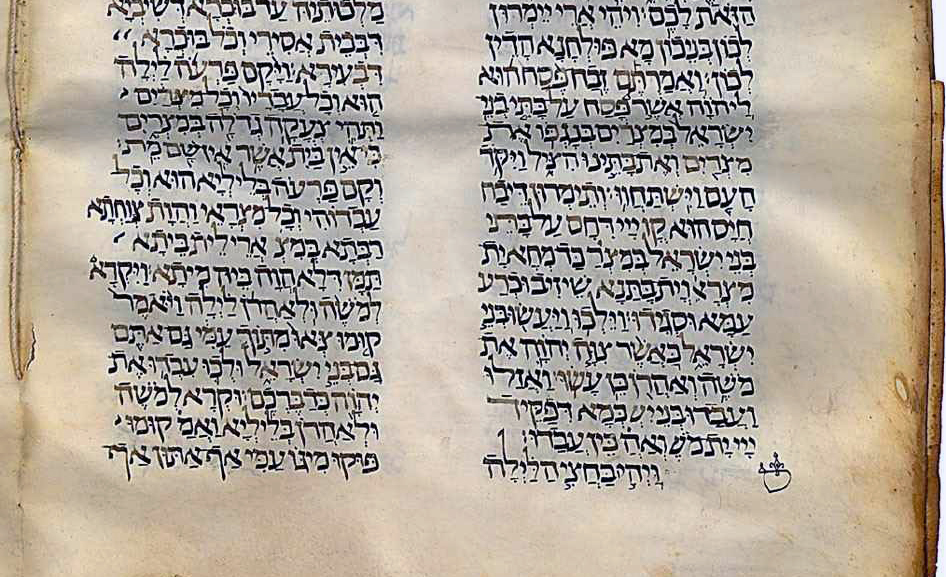

To see how this code switching (as linguists would call it) functions, let’s take a few well-known lines from the Gemara’s tractate of B’rakhot. They start, as do all Talmudic passages, with the Mishnah of which they are an explication. Here it is, first in its pure Hebrew and then in my English translation.

אימתי קורין את שמע בערבין? משעה שכוהנים נכנסים לאכול מתרומתם עד סוף האשמורה הראשונה, דברי רבי אליעזר. וחכמים אומרים: עד חצות

“When is the Sh’ma [the “Hear O Israel” prayer] recited in the evening? From the time the priests [in the Temple] sit down to eat their portions until the end of the night’s first watch: so says Rabbi Eliezer. But the [other] sages say: until midnight.”

And here is the opening part of the Gemara’s commentary on these lines, again translated by me. I have indicated its Aramaic by ordinary print and its Hebrew by bold print.

From what place is the Tana [the author of the Mishnaic dictum under discussion] speaking when he asks “When?” Moreover, why does he teach about the evening prayer first? [The answer is that] the Tana leans on the biblical verse, “And when thou liest down to sleep and when thou risest.” Thus, we learn: the time for the recital of the Shema of lying down to sleep is from the hour that the priests assemble to eat their portions. Or if you prefer, you can say: the Tana teaches us on the basis of the Creation of the World, for it is written: “And there was evening, and there was morning, the first day.”

The Gemara asks two questions. The first is: how does the Mishnah know that a Jew is required to recite the Sh’ma in the evening? To this the answer is that the Bible commands it when it says (Deuteronomy 6:6-7), “Hear O Israel [sh’ma yisra’el], the Lord is our God, the Lord is one. . . . And these things that I command you today shall be in thy heart, and thou shalt teach them to thy sons and speak of them when thou sittest at home, and when thou goest upon the roads, and when thou liest down to sleep, and when thou risest.” “When thou liest down to sleep and when thou risest,” the Mishnah holds, refers to the evening and morning prayers in which the Sh’ma is said.

The second question is: why does the Mishnah begin by discussing the rules for the evening Sh’ma rather than for the morning Sh’ma? To this there are two equally acceptable answers, one being that this is the order in Deuteronomy and the other that this is the order in which the two times of day were created at the world’s commencement.

The Gemara’s text is a simple one as texts in the Gemara go, but let’s now ask a third “when” question: when is the text in Aramaic and when is it in Hebrew?

Here, too, the answer isn’t complicated. The text is in Aramaic when it is framing a sentence; it is in Hebrew when this sentence contains a biblical or Mishnaic source or a religious concept like “the evening prayer,” “the time for the recital of the Sh’ma,” or “the Creation of the World.” Aramaic functions as the basic format of the discourse. Hebrew is slotted into this format when the occasion calls for it.

This is the general rule with discussions of Jewish law (halakhah) in the Talmud. Their participants, whether actual speakers in real discussions whose words were transcribed or remembered, or editorial creations, or both (we don’t know enough about the editorial process behind the Talmud to say), converse with each other—sometimes questioning, sometimes reasoning together, sometimes arguing—in Aramaic. But because they are rabbis steeped in, and talking about, Jewish tradition, they are constantly inserting Hebrew words and phrases into their conversation. It’s the way their thought processes work.

When you think of it, this is the way all Jewish languages and sociolects have worked, whether it’s Judeo-Arabic, or Judeo-Italian, or Judeo-Spanish, or the Judeo-German that is better known as Yiddish. Some, like Yiddish, have used Hebrew more liberally, others more sparingly, but all have had a significant Hebrew component. This is what makes them a Jewish form of speech. Yiddish, for instance, also varies from German in grammar, sentence structure, and its large Slavic vocabulary, but none of these things makes it distinctly Jewish. Only Hebrew does.

The contemporary form of English known as “Yeshivish” or “Ḥaredish” is the same. Here, too, English is the format into which a Hebrew representing source language or rabbinical concepts is slotted. Take the following actual utterance in Yeshivish, for example, culled from a magazine article about such speech (the Hebrew, with its Ashkenazi pronunciation, is again in bold print):

He caused a lot of nezek [harm], but l’basoif [in the end] he was moideh b’miktzas [admitted partial responsibility] and claimed it was b’shoigeg [unintentional].

It’s really no different from the language of the Gemara. Indeed, the Gemara is the archetype of such language, its oldest example. It illustrates not only how Jews have lived since ancient times in a state of diglossia, a knowledge of Hebrew accompanying the language of the region in which they lived, but how they have also code-switched regularly, leading some cases to a full Hebrew-local language fusion.

Adin Steinsaltz understood this well, which is why he wisely did not let his Hebrew translation of the Gemara supplant its Aramaic-Hebrew text. Rather, he chose to print the translation in a side column, as the commentaries of Rashi (whom he has included) and other talmudic exegetes have traditionally appeared, leaving the original text in the center of the page. The resulting bilingual edition allows the Hebrew reader whose Aramaic is not up to par to follow both the meaning of the original text and the code switching that continually takes place in it. It gives us a glimpse into the birth of all the Jewish languages that followed.

More about: Adin Steinsaltz, Gemara, History & Ideas, Religion & Holidays, Talmud