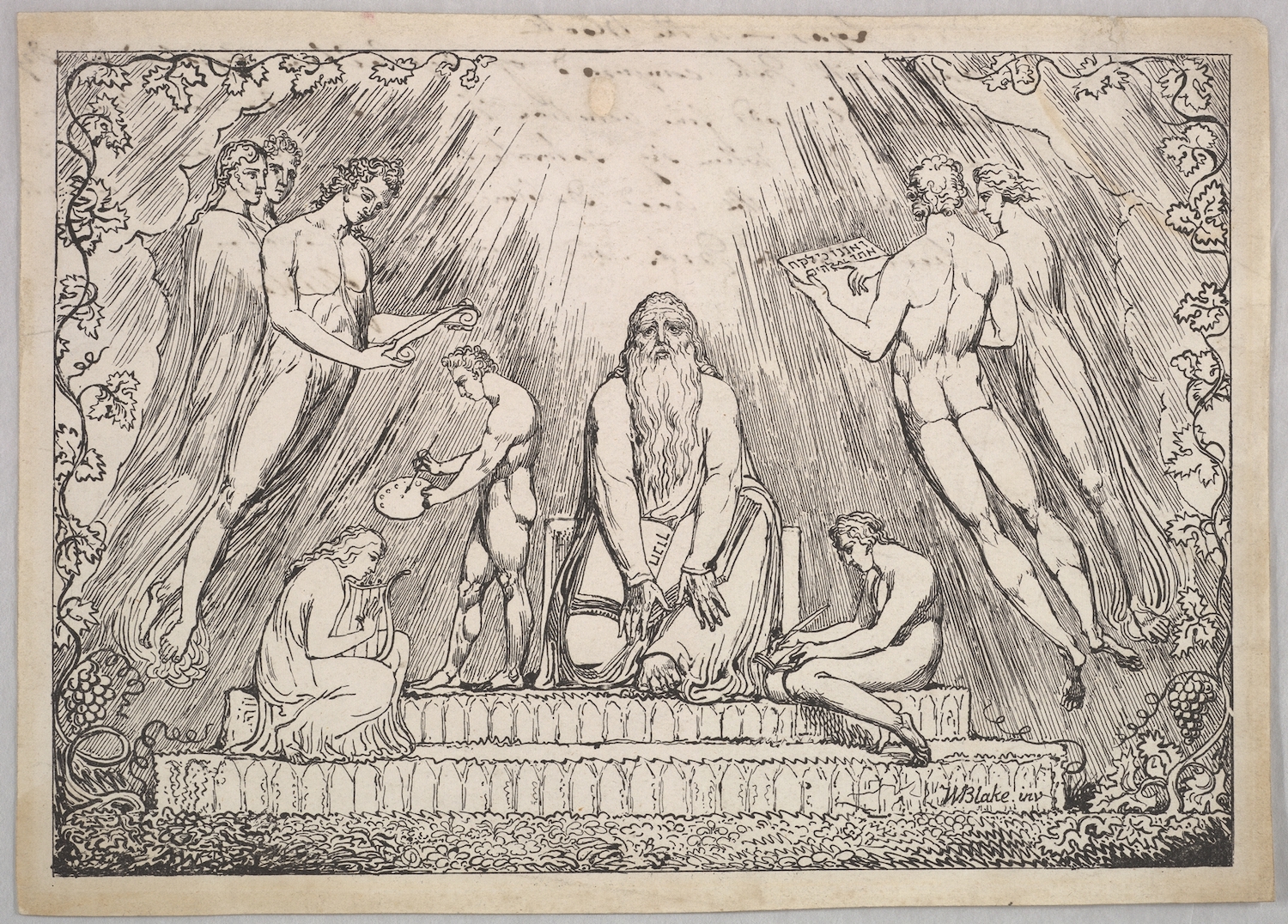

A lithograph of the biblical figure Enoch by William Blake, 1806–7. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For the Son of Man will come in the glory of his Father with His angels, and then he will repay everyone according to his deeds. Truly I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.

And one group of them will look at the other;

and they will be terrified and will cast down their faces,

and pain will seize them when they see that Son of Man sitting on the throne of his glory.

And the kings and the mighty and all who possess the land

will bless and glorify and exalt him who rules over all, who was hidden.

For from the beginning the Son of Man was hidden,

and the Most High preserved him in the presence of his might,

and he revealed him to the chosen. . . .

And all the kings and the mighty and the exalted and those who rule the land will fall on their faces in his presence;

and they will worship and set their hope on the Son of Man,

and they will supplicate and petition for mercy from him.

One of the passages above is Jewish, and the other Christian. But which is which? Readers can surely be forgiven if they are not confident of an answer. For all the differences between Judaism and Christianity on the issue of the identity of the messiah, the two passages clearly come out of the same world of thought. This conceptual compatibility, in turn, suggests that the perception of profound differences, if not diametric opposition, between Jewish and Christian messianic theologies is ill-informed and does not conform to the historical record—or at least the historical record at the time Christianity arose.

In fact, the first passage is from the New Testament (Matthew 16:27–28) and purports to be the words of Jesus himself. The second is from a Jewish text found in First Enoch (62:5–9) and written a very few decades before or after Jesus’ birth. Like almost all the Jewish literature dating from those decades, First Enoch is not included in the Jewish scriptural canon that we now have, nor, apparently, was it known to the rabbis who were to leave us the Talmud centuries later. Contemporary Jewish readers can be readily pardoned if the book and its worldview seem foreign to them.

One of the elements that may first seem least Jewish is the notion that the awaited redeemer is primordial, “hidden,” in the words of this text, “from the beginning.” The parallel with the language of a famous New Testament passage is patent: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. . . . And the Word became flesh and dwelled among us, and we saw his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:1, 14).

Indeed, this notion of a figure who existed before the creation of the world and will eternally remain in God’s presence seems to collide head on with what most Jews consider the very animating essence of Judaism—monotheism, the confession that “the Lord is God in heaven above and on the earth beneath; there is no other.” This is not just a quotation from the Torah (Deuteronomy 4:39); it is also part of an affirmation of faith that in the traditional liturgy closes every prayer service, and for good reason. As Maimonides, the great 12th-century codifier and philosopher, wrote, to believe in the oneness of God is a positive commandment and anyone who thinks there is another god has violated “the great principle upon which everything depends” (Mishneh Torah, Yesodey ha-Torah 1:6).

How then can Jews have ever affirmed that there was a second figure enthroned in heaven?

According to Two Gods in Heaven: Jewish Concepts of God in Antiquity, a new book by the highly regarded scholar of ancient Judaism, Peter Schäfer, the answer is as simple as it is disturbing (at least to Jewish traditionalists). The understanding of God among Jews in the period at issue was more complicated than an overgeneralized appeal to Deuteronomy or an anachronistic citation of Maimonides conveys. “Monotheism,” in fact, is a sadly inadequate cover term for the range of Jewish thought in the period in question, much of which was, on balance, quite accepting of the notion that there was a second God. For all the controversy it may stir among the faithful, Schäfer’s book is irenic in tone and, though massively learned, also clear and accessible.

Whether it really makes a convincing case for “two Gods in heaven” in ancient Judaism, however, is a more complicated question.

I.

As often in the cases of both Judaism and Christianity, the origin of the issue lies in a passage from the Hebrew Bible, in this case Daniel 7:9–14:

9 I watched until thrones were set in place, and an Ancient of Days (‘atiq yomin) took his seat; his clothing was white as snow, and the hair of his head like pure wool; his throne was fiery flames, and its wheels were burning fire.

10 A river of fire issued and came forth from before him. Thousands upon thousands served him, and myriads upon myriads stood attending him. The court sat in judgment, and the books were opened . . .

13 As I watched in the night visions, I saw one like a human being coming with the clouds of heaven. And he came to the Ancient One and was presented before him.

14 To him was given dominion and glory and kingship; all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that shall not pass away, and his kingship is one that shall never be destroyed.

The most pressing problem—and one much discussed by scholars—is the identity of the “one like a human being” who receives eternal kingship from the enthroned “Ancient of Days.” On the basis of an overliteral translation of the Aramaic (bar ’enash), the mysterious figure has usually been identified as the “Son of Man.” Schäfer glosses the phrase to mean simply “someone who looks like a human being” and identifies its referent as the archangel Michael. “Elevated to a godlike status,” he writes, “this angelic figure becomes the origin and point of departure for the later binitarian figures who will reach their culmination and end point in Metatron.”

“Binitarian” is a term that modern scholars have coined to refer to a belief that divinity exists in two figures, more or less on the model of the Christian trinitarian theology, which maintains that the one God exists in three persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. As Schäfer and other scholars have shown in recent years, binitarianism was very much alive in ancient Judaism, and “Metatron” (who, as we shall see, also appears in rabbinic literature) was a highly important figure in it. It is this heavenly figure who, in Third Enoch (a Hebrew book from the second half of the first millennium CE), is described as the “Lesser God” or “Younger God.” What is more, the same book reports that the biblical antediluvian figure Enoch actually was transformed into Metatron and thus divinized. This brings us, Schäfer points out, to a place “not all that far from the association of a God-father and God-son as is familiar in full-blown form from Christianity.” The “Younger God” Metatron, formerly the human being Enoch, is to the God of Israel as Jesus, the Son of God, is to God the Father in Christian theology.

In sum, as different as Judaism and Christianity now seem on the whole question of the divine father and son, there were actually tangents between them on this point as well as genetic connections.

One of those tangents centers on a passage that, as we saw, is part of the Jewish scriptural canon, the passage in Daniel 7 in which the “Son of Man” receives eternal kingship from the “Ancient of Days.” For already earlier, even before the New Testament was written, another Jewish book, the Similitudes of Enoch, had combined Enoch and the Son of Man. This, too, is, “nothing less than the transformation of the human Enoch into a divine being,” Schäfer writes. Hence, the intellectually honest historian of Second Temple Judaism must reckon with two divine figures, the greater or older God and the lesser or younger God whom he elevates in what is one of the most consequential moments, if not the most consequential moment, in the drama of God’s dealings with humankind.

The pattern, in fact, is common in the period and hardly restricted to literature about Enoch. In the book of Proverbs, the figure of Wisdom claims that God created her—or is it “begot” her?—before the earth and heaven were formed (Proverbs 8:22–31). In the Wisdom of Ben Sira (or Ecclesiasticus), a book composed by a Jewish sage early in the 2nd century BCE and quoted respectfully by talmudic rabbis later, Wisdom is enthroned in heaven, holds sway over all peoples, yet takes up residence on Mount Zion, site of the Jewish Temple. Somewhat later, in the Wisdom of Solomon, she again “sits on the throne at God’s side” but also is, in Schäfer’s words, is “the archetype of his perfection and at the same time his emanation, which imparts God’s glory and active workings into the earthly world.” The Dead Sea Scrolls, too, present evidence for Jewish binitarian theology. In one of them, from the latter half of the 1st century BCE, a human being boasts of having taken a throne in the heavens themselves and having been “reckoned with the gods”; he also speaks, in terms reminiscent of some of Jesus’ speeches, of his incomparable grief and suffering.

In a very different idiom but broadly reflecting a similar conception, the Alexandrian Jewish philosopher Philo (ca. 20 BCE–50 CE) speaks of the Logos and Sophia (or Wisdom) as God’s “elder and firstborn son’” and “younger son,” respectively. The former is “God’s actual creative power,” Schäfer explains, while the latter “is responsible . . . for the world perceived by our senses.” As he sees it, the language is the language of philosophy, but the underlying theology is deeply indebted to Jewish binitarian thinking and, as in all these examples (and others he discusses), the modern term “monotheism” is not helpful to the effort to appreciate the deeper dynamic and the complexity of the concept of God in the period. Christianity did not create the template but rather sought to fit the figure of Jesus into it in the role of the Son of Man/Son of God/Son of David already well established in the Judaism of the time.

II.

Religiously committed Jewish readers may well concede all this but still find it utterly irrelevant to the tradition they practice. For all forms of modern Judaism descend from the rabbinic tradition, the Judaism of Talmud and midrash, and not directly from the earlier currents of Second Temple Judaism represented in almost all the sources we have mentioned so far. Indeed, most of those books were unknown to the talmudic rabbis, and, with the exception of Proverbs and Daniel, none of them can be said to command canonical authority today.

In both Christian and Jewish quarters, as Schäfer describes the situation, there are worrisome motivations to disconnect the binitarian theology from the rabbinic tradition:

On the one side are efforts by New Testament scholars to highlight the novelty of the New Testament and distance it from contemporary Judaism. They tend to downplay connections with the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha [that is, Second Temple sources that are not canonical for rabbinic tradition], and judge skeptically any attempts to view the New Testament as primarily Jewish scripture. On the other side are efforts by Jewish-studies scholars who try to link the New Testament as smoothly as possible with Second Temple Judaism, aiming to dissociate it from later rabbinic Judaism.

Whether or not these trends are still as prevalent as he implies, Schäfer convincingly shows that such a dissociation is not credible, for binitarian theology is also present in the Talmud, though—and this is of the utmost importance—also sometimes ferociously challenged there. Consider a debate about the meaning of that generative passage in Daniel 7, specifically verse 9, in which the seer “watched until thrones were set in place” and yet only few words later the same noun appears in the singular: “His throne [that is, the throne of the Ancient of Days] was fiery flames.” Is there more than one throne or not? By obvious implication, this question raises another, which is of the highest theological import: is the “one like a human being” (or, “Son of Man”) who receives kingship enthroned in the heavens with the Ancient of Days or not?

A statement in the Babylonian Talmud (Ḥagigah 14a) in the name of Rabbi Akiva (died ca. 135 CE), a hugely important figure in early rabbinic Judaism, proposes what Schäfer sees as a binitarian resolution:

There is no contradiction: one (throne) for Him [the Ancient of Days], and one (throne) for David: for it has been taught (in a baraita): one was for him and the other was for David—these are the words of Rabbi Aqiva. [Schäfer spells Akiva’s name this way.]

The notion in this baraita (a statement attributed to an early rabbi in a later source) that David—that is, the ancestor and archetype of the messiah—is enthroned on high immediately prompts a sharp rebuke:

Said Rabbi Yose the Galilean to him: Aqiva, how long will you treat the She’khinah [that is, “the indwelling presence,” meaning God] as profane! Rather, one (throne) was for justice (din) and one (throne) was for mercy (tze’daqkah).

The passage goes on to present evidence that Rabbi Akiva accepted the correction, although this is then followed by another scathing rebuke of him, this time recommending he not comment on such matters at all but restrict himself instead to technicalities of ritual law. Revealingly, this is, in turn, followed by an interpretation of the two “thrones” in Daniel 7:9 functioning as one, the first for the Ancient of Days to sit upon and the second to serve as the same figure’s footstool. This third interpretation removes the whiff of dualism inherent even in the notion that God’s justice and His mercy each has its own throne. Now only one personage is enthroned in heaven; any suggestion of duality within the one God has been eliminated. Binitarianism has been unambiguously repudiated.

Schäfer doubts the historical reliability of this exchange between early rabbis in the Land of Israel in a source from centuries later in Babylonia. The attack is thus not on the historical Akiva, he writes, “but instead on Jewish opponents from the direct environment of the [Babylonia Talmud’s] redactor.” And why did the interpretation attributed to Rabbi Akiva evoke such ferocious rejections? It was “precisely because of the Son of Man–Messiah Jesus in the New Testament.” In other words, the central role that the passage in Daniel 7 and its Jewish reverberations had come to play in Christianity rendered its binitarian implications too dangerous for the talmudic redactors to acknowledge. The Ancient of Days had thus never handed over kingship to the “one like a human being,” or Son of Man, at all. Kingship remains God’s alone.

The rebuke of Rabbi Akiva is not the only passage in the Babylonian Talmud or other relatively late rabbinic literature in which binitarian theology is disavowed. In one famous, and famously difficult, passage (Ḥagigah 15a), Rabbi Elisha ben Avuyah, the archetypical heretic of rabbinic Judaism—and thus known as “Aḥer” (“Other”)—beholds the heavenly figure Metatron seated in the heavens and exclaims, “Are there perhaps—God forbid!—two powers [in heaven]!?” Metatron is then led out and flogged for not having risen before Aḥer.

In Schäfer’s interpretation, the point is that “Metatron should have instantly stood up when Aḥer entered the seventh heaven in order to make it absolutely clear that he is not a second God, but only an angel.” Although Schäfer thinks “this ‘sitting’ is not the excessive enthronization of Metatron as in 3 Enoch but instead simply results from the fact that Metatron functions in heaven as a scribe,” it is hard not to detect here yet another echo of the key scene in Daniel 7 that begins when thrones are set up and the Ancient of Days takes His seat on His heavenly throne. Metatron (who, it will be recalled, is described in Third Enoch as nothing short of the “Lesser” or “Younger God”) led Rabbi Elisha ben Avuyah astray—and is rightly punished for it.

Such, it can be inferred, would be the fate of any Jew who subscribes to the belief in “two powers in heaven”—a belief that did not disappear with the Second Temple but was still alive centuries later, even in rabbinic circles, as Schäfer shows.

III.

Two Gods in Heaven: Jewish Concepts of God in Antiquity is a worthy successor to Peter Schäfer’s earlier and longer works, The Origins of Jewish Mysticism and The Jewish Jesus: How Judaism and Christianity Shaped Each Other, both of which it recapitulates to some degree but also updates. It offers clear and expert analysis of little-known literature and puts better known sources into helpful perspective. Particularly productive is the author’s preference “to define the relationship between Judaism and Christianity not as linear from the mother to the daughter religion but rather as a dynamic, lively exchange between two sister religions.” For both rabbinic Judaism and Christianity grew out of the rich soil of Second Temple Judaism, which was itself a continuation, but also a set of reinterpretations, of earlier stages in the religion of Israel as evidenced in the Hebrew Bible.

Potential readers should be aware, however, that despite its subtitle, the new volume does not really discuss the range and complexity of Jewish concepts of God in antiquity—which would require a much longer study—but instead focuses solely on the notion of “two Gods in heaven.” But even that title seems overstated in light of the author’s actual claims. Is he really discussing a belief that there were two Gods? The language Schäfer employs suggests something much less bold. Consider these phrases: “elevated to quasi-godlike status,” “rather like God unique among the angels,” “a human being who becomes God, or rather godlike,” “the Messiah-King elevated up to heaven,” “placed at an almost equal level with God.”

But what can these qualifiers mean? Being almost equal with God is like being almost pregnant: no matter how lofty the figure is in the cosmic order, he is either equal with God—and there are thus two Gods—or he is not, and God remains unique.

On this, a comparison of Jewish binitarianism with Christian trinitarianism is enlightening. According to orthodox trinitarian theology, as defined by the Council of Nicaea (325 CE), God has always been triune—that is, one God in three “persons.” God the Father is thus no older than God the Son, and God the Son is no younger than God the Father. For the one God was always, in the term from John Donne’s famous sonnet, “three-person’d”; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all eternal. At a certain point in history, as the highly influential Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed states the matter, the Son became incarnate in the man Jesus, but the Son had always existed, “eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one Being with the Father.”

To outsiders, including many Jews and Muslims, the Trinity has often seemed to involve three gods, but to orthodox Christian believers God is, rather, triune, three-in-one. In the case of the Jewish binitarianism that Schäfer discusses, by contrast, it is hard to see how the figures who have been elevated into the highest heaven and granted great authority—whether Michael, Enoch, David, the Messiah, or whoever—can be called “God” at all. If you depended on God to elevate you to the rank of a God, you are still not God: He is. The classical rabbinic term for this picture is therefore more accurate—“two powers (re’shuyot) in heaven,” not “two Gods in heaven.”

There is another significant difference between the two traditions, one that Schäfer notes well:

The most striking difference between the binitarian ideas of postexilic Judaism and the Christology of the New Testament is that in Second Temple Judaism, the godlike or semidivine figure next to God never becomes a human being. . . . The humanness of the “human” who becomes “God” in Judaism is extinguished and no longer has any meaning for his mission on earth. In Christianity, on the other hand, the incarnation of God is a basic component of the process of redemption.

To this, we must add another key difference, one that derives from considering the development of the two traditions over time. In the Christian case, the notion of the human Jesus as, minimally, standing in a unique relationship to God and, maximally, being the very incarnation of God Himself was central to the tradition. Eventually, as the creed quoted above affirms, full-blown trinitarianism and a belief in Jesus as God incarnate became for many the touchstone of authentic faith. It remains so, at least officially, for the majority of professing Christians to this day.

In the case of Judaism, the Enoch books and the texts of Hekhalot mysticism (a genre of Jewish mysticism probably dating from the second half of the first millennium CE) on which Schäfer focuses, however large or small the groups who authored and treasured them were, have moved in the opposite direction, to the margins, whereas the Babylonian Talmud, with its rebuke of Rabbi Akiva and its flogging of Metatron, has moved to the center. Thousands upon thousands of Jews study Talmud every day. The Enoch books and the Hekhalot texts are pretty much known only to specialized scholars of Jewish studies. That alone constitutes a crucial difference and one that Schäfer would have been wise to confront.

IV.

Let us, finally, return to the question of monotheism. In Schäfer’s view, “Monotheism was to find its purest form in medieval Jewish philosophy.” Whether he is right depends, of course, on just what is meant by the term and what sort of factors are thought to contaminate it.

As a broad generalization, we can say that in the Hebrew Bible the insistence on “monotheism” is based in one of two concepts. The first is the covenantal norm that the people of Israel is to demonstrate exclusive loyalty to the God known by the Hebrew four-letter proper name (conventionally rendered into English as “the LORD”). He is their God, He alone. The second concept is the confession that the Lord has won a stupendous victory that demonstrates both His own incomparable power and the weakness, insubstantiality, and sometimes even nonexistence of the other gods. The Lord’s triumph establishes His mastery of the entire world. He alone is its rightful ruler—“the great king over all gods” (Psalm 95:3).

Neither of these two modes of ancient Israelite monotheism requires that God be conceived as solitary. Indeed, some biblical texts depict the Lord as a king holding court in the divine assembly, asking questions and receiving answers from His cabinet, as it were, and handing out assignments; other passages depict Him as having an array of agents and emissaries, human or divine (for example, 1Kings 22: 19–23; Job 1–2). Still others speak of His having sons, the people Israel, for example, or the royal successors to King David (for example, Deuteronomy 14:1; 2Samuel 7:14). In one psalm, God promotes David into the role of His firstborn and the highest king on earth, into whose hands He commits the control of cosmic powers (Psalm 89:26–28).

All this is a logical expression of the fact that in the Hebrew Bible, God is conceived as personal and relational. His sociability extends into the heavens, so to speak. Neither His exclusive claims, His uniqueness, nor His incomparability entail that He be a loner, nor does the presence of other beings in the heavens suggest that the monotheism of the sources that speak of them is somehow impure—unless, that is, one stipulates that in a monotheistic system, God must be radically alone. But if such a stipulation be accepted, then we must conclude not only that Second Temple and later Jewish binitarian theology falls short of monotheism but also that most of the Hebrew Bible does as well.

In the Second Temple period, however, as the other members of the divine assembly come to be described with a higher degree of individual identity, a danger to monotheism in these biblical modes appears: the entities associated with God, or at least those He has elevated to a lofty rank—especially one who has been awarded a throne—may come to be perceived as having authority of their own and thus receive worship in their own right, undermining His exclusive claims on the service of human beings and calling His incomparability and uniqueness into doubt as well. Quite apart from the equation of “the Son of Man–Messiah Jesus in the New Testament,” the belief in “two powers in heaven” threatened to subvert the very foundation of monotheism in either of those two biblical modes.

The rabbis who spoke of it as a heresy surely knew that.