Rosh Hashanah at the Great Synagogue in Paris on September 4, 2018. YOAN VALAT/AFP via Getty Images.

Why are the High Holy Day services so long?

One answer might be that Jews like to pray, and that there’s no better opportunity for doing so than Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur—especially the latter, when there are no holiday meals to get home to and prayers can take your mind off an empty stomach.

A second answer, which doesn’t contradict the first but explains its mechanism, is piyyut.

Piyyut is the Hebrew word both for liturgical poetry in general and for (since Hebrew doesn’t have an indefinite article) a single liturgical poem. It comes from the Greek poietes, poet, or poietikos, poetry, and it entered the Hebrew language in the early post-talmudic age. It is the large number of piyyutim in the High Holy Day service, as opposed to everyday Jewish prayer, that is the main reason for their lengthiness. (Piyyutim, though not as many of them, are also recited on other Jewish holidays.)

A composer of piyyut is a paytan, and the three great early paytanim, Yosi ben Yosi, Yannai, and Eliezer Hakalir, all lived in Palestine, as far as can be determined, in the 6th and 7th centuries CE, which is when the genre originated. Their poems, as well as those of their many successors, were meant to be read or sung at various junctures in the synagogue service as commentaries or embellishments on the canonical prayers, so that their inclusion was optional and left to the discretion of individual congregations and communities. This is why, to this day, most major divergences between different Jewish liturgical traditions have to do with them.

But the many piyyutim in the High Holy Day service not only add to its length. They also detract from its comprehensibility, because their Hebrew tends to be extremely difficult. For those worshipers who, during the year, attend synagogue only on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and are unlikely to know enough Hebrew to grasp the meaning of even simpler prayers, this is unlikely to be noticed. For more regular synagogue goers, however, it is an impediment. Accustomed to understanding what they are saying when they pray, they are confronted by the High Holiday’s piyyutim and long stretches of reciting what may almost seem gibberish.

Indeed, the Hebrew of the early paytanim, who are the ones most represented in the Siddur, is not only more compressively dense, more puzzlingly allusive, and more daringly and sometimes bizarrely innovative in its use of language than any Hebrew that came before it. It is also more so than any Hebrew that came after it.

There are historical reasons for this. The early paytanim were living in an age, right after the redaction of the Talmud, when Hebrew, which had ceased to be spoken by the Jews of Palestine toward the end of the biblical period, had also ceased to be the language used by rabbis when discussing Jewish law and tradition. (This had become, as the text of the Gemara demonstrates, Aramaic.) It was no longer spoken by anyone—and when speech no longer exists to set a standard of usage, there is no longer any way to determine what in a language is “natural” and what is not. When nothing is unnatural, everything can be considered to be natural.

Yet if this posed a problem, it was also a challenge and an opportunity. A situation of “anything goes” is one that invites experimentation and virtuosity. The language of the Tannaim and Amoraim of the Mishnah and the Gemara is a tool, not an end in itself. It never says “Look at me!” or “Let me show you what can be done with me!” The language of the early paytanim does just that. It seeks to stretch Hebrew to its limits, to explore every possibility that the language has to offer, and it sometimes does this so acrobatically that it is hard to follow.

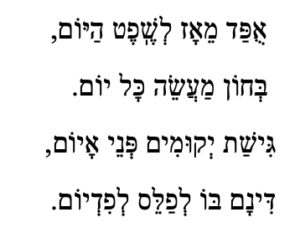

Let us take a small example. A Rosh Hashanah piyyut found in many prayer books is Eliezer Hakalir’s Upad mey’az l’shefet ha-yom, which is placed near the beginning of the cantor’s repetition of the Sh’moneh Esreh or the “Eighteen Benedictions” of the musaf service. It occurs right before the second of these benedictions, “Blessed art Thou, O our God king of the universe, who protected Abraham,” and it is a poetic gloss on the first of them, which invokes the three Patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Here is its opening Hebrew stanza:

And here is an English transliteration of it:

Upad mey’az l’shefet ha-yom,

B’ḥon ma’asei kol yom.

Gishat y’kumim p’ney ayom,

Dinam bo l’fales l’fidyom.

The first thing one may notice about this stanza is that it is rhymed. Rhyme in Hebrew poetry is an innovation of the paytanim. Very often this is monorhyme, i.e., all the rhyming words have the same last syllable, which in this case is –yom. The next obvious thing is that the poem is what is known as an abecedarius—that is, that the first word of each line starts with one of the letters of the alphabet, which follow each other in order. (Thus, line 1 of this poem starts with an alef, line 2 with a bet, and so on.) Although abecedarial verse is found in the Bible, in the books of Psalms and Lamentations, it is infrequent there. In piyyutim, it is very common.

Rhyme and abecedarianism, of course, don’t in themselves make a poem more difficult to understand, though they do sometimes compel a poet to labor a word or the syntax of a sentence in order to achieve them. But let’s put that aside and offer a rough translation of Hakalir’s first stanza, with some of the Hebrew in brackets:

(It was) Accoutered [upad] from the first for the judgment [shefet] of the day,

To probe [b’ḥon] the deeds of each day.

Mortals approach the Fearsome One [ayom]

To make way [l’fales] a verdict for redemption [l’fidyom].

The first line of this stanza alludes to a midrash, which is something the paytanim frequently do without making their allusions explicit, thus putting our knowledge of rabbinic tradition to the test. God, according to this midrash, finished the work of Creation on Rosh Hashanah, which is thus both the first day of the new year and the first day of the completed universe, as well as the first of the ten days of judgment ending with Yom Kippur.

Apart from its allusion that may elude us, this line contains two odd linguistic usages. The first is upad, which is the passive or pu’al form of the verb afad, to don or accouter. This verb, formed from the noun efod, the breastplate of the high priest, occurs only once in the Bible, and was never used before Hakalir in a pu’al form. Why did he do this, making God the couturier of a day of judgment? Partly to show off his ingenuity, and partly because he wanted the cosonance of the p/f and d/t in upad and shefet, judgment. Although consonance is found in biblical poetry, too, it is the paytanim who first go in for it in a big way.

Shefet is also Hakalir’s invention. Although shafat, to judge, is an ordinary Hebrew word, the noun for judgment formed from it is mishpat. What made Hakalir, though he was not violating the rules of Hebrew morphology, decide to substitute—quite unnecessarily, it might seem—shefet for the more common formulation? Again, he was not merely showing off his virtuosity. Shéfet is stressed on its first syllable, mishpát on its second—and Hakalir wanted the former for rhythmic purposes, to give the line a better, more skipping flow. Normally, poets faced with a word that does not suit their purposes, look for another one. Hakalir preferred to make one up.

He also didn’t mind the inconsistency of using two different forms of the Hebrew infinitive in the same stanza, b’ḥon, which is the biblical form, and l’fales which is the Mishnaic form, nor saying “to make way a verdict,” which doesn’t make much more sense in Hebrew than in English. Pidyom, redemption, is the final word in the stanza, and it too is forced. A rare biblical variation on its more common form of pidyon, it is there for the sake of the rhyme, too.

And then there’s another rhyming word, ayom, “the Fearsome One,” referring to God. The prophet Habakkuk says of God that ayom v’nora hu, “He is fearsome and terrible,” but no one before Hakalir thought of calling Him just ayom, turning an indefinite adjective into a noun in defiance of Hebrew grammar and, possibly, of his readers’ understanding.

The first stanza of Upad mey’az is the poem’s simplest. From here on, the poem gets more complex and obscure, so that to most educated Hebrew speakers today, even many religiously observant ones, it is all but incomprehensible. And yet, ironically, the paytanim’s contribution to the development of Hebrew, modern Hebrew too, was great. It was they who first thought of expanding the Hebrew language—then no longer able to grow naturally because no longer spoken—by inventing new words on the basis of existing roots, giving old ones new meanings, and exploring new ways of constructing phrases and sentences. They gave Hebrew a plasticity that served as a model for future innovators, starting with the great Arabic-Hebrew translators of the Middle Ages and continuing through Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and the pioneers of contemporary Israeli speech.

Between the understandable Hebrew of today and the understandable Hebrew of the Bible, Talmud, and Midrash, the often not understandable piyyutim are an indispensable link. You might think of that the next time (which may be soon) that you wish there were less of them.

A happy 5781 to you all!