Once a week, Mosaic has taken to publishing brief excerpts of Leon R. Kass’s new book on Exodus, Founding God’s Nation. Curious about one of the foundational texts of the Jewish tradition? Read along with us. To read earlier excerpts, go here.

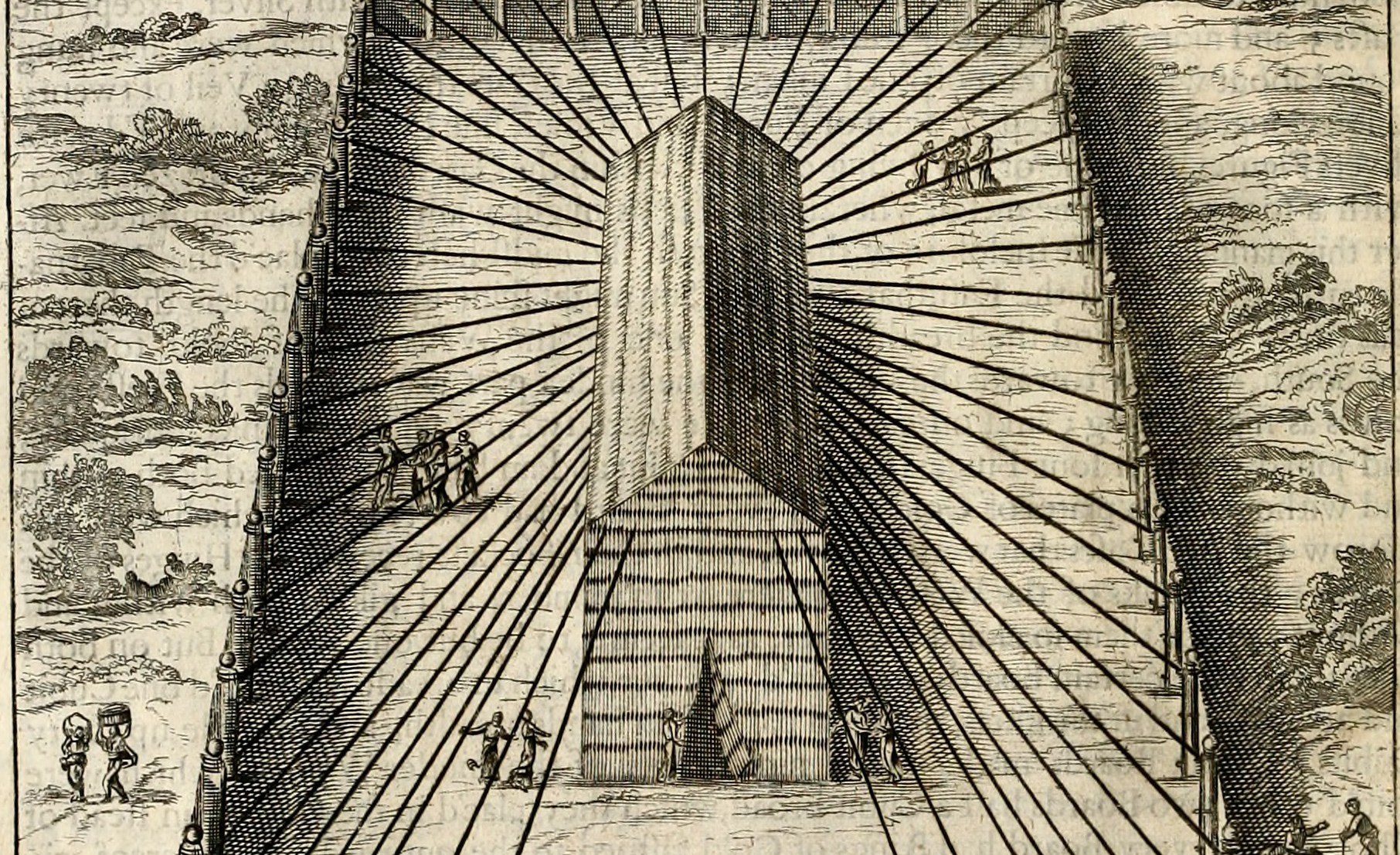

This week, Jewish communities all over the world begin their study of Exodus 27:20-30:10, a portion of the text named T’tsaveh. Having instructed Moses in the construction of the Tabernacle, the Lord now begins to discuss the officials and priests who will minister there. Much of this week’s passage is concerned with an elaborate description of priestly vestments, and with various sacrifices that priests will perform. Then, God reveals the purpose of the Tabernacle, the subject of this week’s excerpt from Leon Kass.

The point [concerning God’s presence in relation to the Israelites] is made more explicit in the immediate sequel, which provides a ringing conclusion to the instructions for the Tabernacle. It offers a surprising revelation about the purpose of the Tabernacle and of the whole story that we have been reading from the beginning of Exodus—even of the entire Torah:

And there I will meet with the Children of Israel; and [the Tent] shall be sanctified by My glory (bikhvodi [the basic form of the noun is kavod]). And I will sanctify the Tent of Meeting (ohel mo’ed), and the altar; Aaron also and his sons will I sanctify, to be priests to Me. And I will dwell among the Children of Israel (v’shakhanti b’tokh b’ney yisra’el), and will be for them a God. And they shall know that I am Y-H-V-H their God, that brought them forth out of the land of Egypt, [so] that I may dwell among them (l’shokhni b’tokham). I am Y-H-V-H their God. [29:43–46; emphasis added]

In these summarizing words, the Lord makes it clear that when He meets with the Israelites “there,” in the Tabernacle—when He reveals Himself to His people through Moses—the place will be sanctified by His glory. It is, finally, not the clothing or the sacrifices or the sprinkling of blood, but only His Presence that will sanctify—make holy—the Tent and the altar and the priests who serve Him. The people and their priestly representatives must properly perform the rituals to “deserve” the Presence, but it is the Presence alone that sanctifies.

There is more good news. Back in Egypt, when the Lord revealed himself to Moses as Y-H-V-H and gave the Israelites His sevenfold promise, He predicted that one day “you shall know that I am Y-H-V-H your God who brought you out from under the burdens of Egypt” (6:2–8). The dispirited people turned a deaf ear (6:9), and since then there has been no explicit mention that they attained any knowledge of God. Here, Moses (also the reader) learns for the first time that, through the Tabernacle, the Lord’s goal of being known by His people will be fulfilled. Even better, that knowledge will not be abstract and remote, but up close and personal.

The Lord ends with a statement of His ultimate purpose: “that I may dwell among them”—shakhanti b’tokham. We have heard these words before, in the brief statement of purpose the Lord offered at the start of His instructions for the Tabernacle (25:8). But now they are fit into a larger context. Through the Tabernacle, the people will come to know something altogether new and decisive about their God. They will not only know Him, Y-H-V-H, as the God Who led them out of Egypt; but they will also know why He did it: so that He might forever after dwell among them. He wants to be known not only as their deliverer from bondage but also as an immediate and permanent Presence in their lives. He wants to be known not as the God of the Mount Sinai experience or as a remote God in heaven but as a Presence in their midst, here and now: as a God—an awesome protector, guide, friend, and judge—in their daily lives.

This self-revelation of Divine intent casts powerful light on all of God’s dealings with the Israelites—and, dare we suggest, on God’s hopes and plans for humankind almost from the Beginning. We understand more clearly why Israel becomes a people here in the desert, with a high sacral calling even before they acquire land, economy, or political institutions. God’s purpose—for them and, through them, for humankind—is more than national liberation, political founding, and decent interpersonal morality (though He surely cares about these moral-political goals). It is more even than righteous and holy conduct. It is, in the end, to make Himself known by His human creatures and to be known in the right way—not only as a mighty power or a wise lawgiver but also as a “Presence.” The benefits of this relationship, strange to say, flow not to humankind alone.

Long ago I pointed out that, uniquely in the history of the world, the Children of Israel become a people before they become a political entity proper—before they have land, an economy, an army, or the institutions of government. Their formation as a people is legal, moral, and spiritual. The Decalogue and the ordinances are to shape their legal-moral character and, to some extent, their spiritual one. But it is only in and through the Tabernacle that their sacral mission is to be fostered and pursued. Paradoxically, it is these concrete rituals, presided over by a priestly technocracy that performs them for the community, that bring Israel to realize the Lord’s ultimate purpose with humankind: not only that human beings shall know about the Lord, but also that they shall know Him intimately as a living Presence in their—our—everyday lives, for our sakes but also for His.

Excerpted and adapted from Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus by Leon R. Kass. Published by Yale University Press in January 2021. Reproduced by permission.

More about: Reading Exodus with Leon Kass, Religion & Holidays