Once a week, Mosaic has taken to publishing brief excerpts of Leon R. Kass’s new book on Exodus, Founding God’s Nation. Curious about one of the foundational texts of the Jewish tradition? Read along with us. To read earlier excerpts, go here.

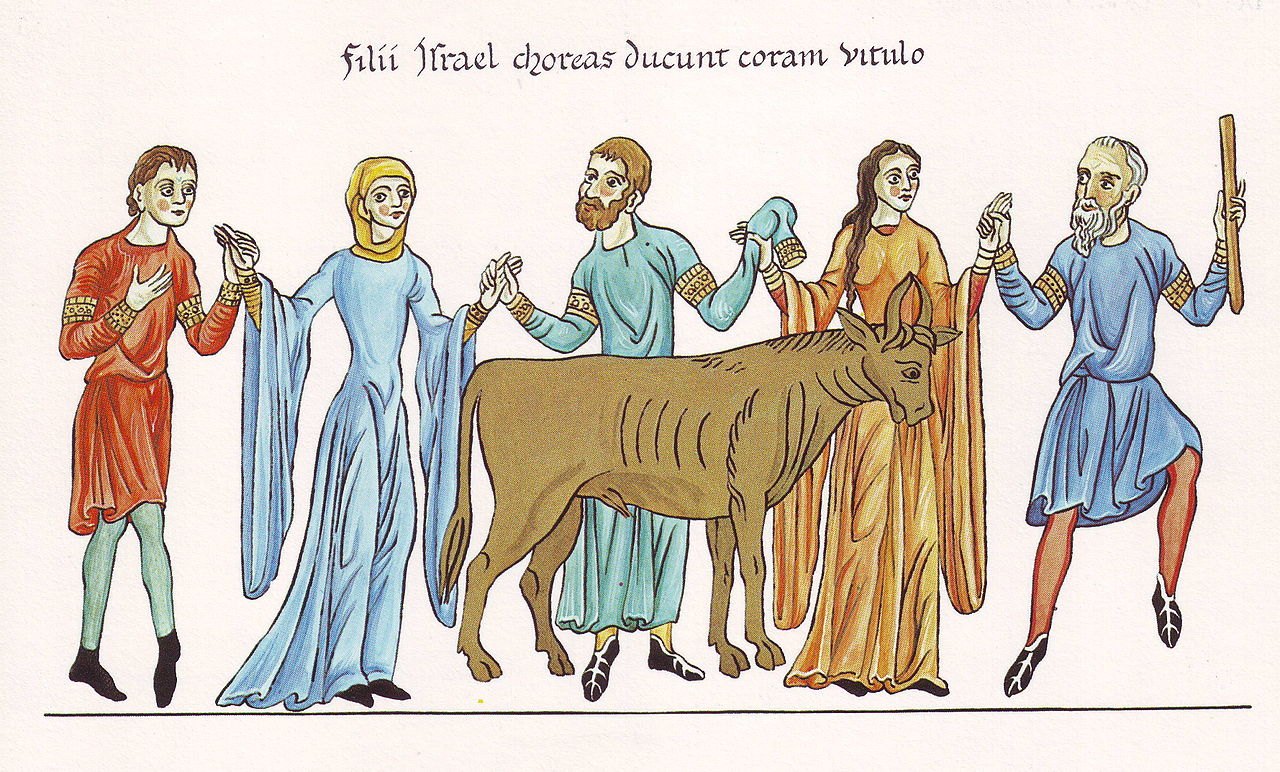

This week, Jewish communities all over the world begin their study of Exodus 30:11-34:35, a portion of the text named Ki Tisa. This portion—the longest in the book of Exodus—includes the episode of the Golden Calf, in which, while Moses remains atop Mount Sinai, the Israelites below fashion from the golden earrings they took from Egypt an idol to worship. Upon learning of this violation of the Israelites’ twice ratified covenantal promise not to worship any other gods, Moses persuades God not to destroy them.

But Moses himself descends from the mountain in order to punish the people on account of this grave sin, and to reestablish order. He does so in one of the most dramatic and violent actions in the book of Exodus. Moses recruits to his side his fellow Levites, and orders that “each man kill his brother and each man his fellow and each man his kin” (Exodus 32:27). Before interpreting Moses’ response, Leon Kass offers a challenge: “Whether or not you like what he did, see if you have a better idea.”

The heart of the action is the division of the camp on the basis of professed loyalty to the Lord. Accomplishing several goals at once, Moses, standing alone in the gate of the camp, recruits allies who want to fight for God: “Who is for the Lord? To me!” Strikingly, only Moses’ fellow Levites—descendants of Levi, the spirited son of Jacob, who (along with Simon) violently avenged the rape of their sister Dinah—answer the call. The Levites alone declare themselves “for the Lord”; the other tribes keep their distance—perhaps by itself a declaration of their continued apostasy.

We must not conclude that the Levites had abstained from worshiping the calf. According to the text, all the people brought their gold earrings to Aaron, and there is no reason to believe that there was less than full participation in the wild festival the next day. The spirited Levites—perhaps fearful of Moses’ wrath and grasping at the chance to become allies in his cause, perhaps also feeling remorse for their complicity in the transgression now that the deed has been exposed as sinful—quickly enlist on Moses’ and the Lord’s side when given a chance of redemption. Violence in defense of their own, we may say, is in their Levite DNA. But here, they shed blood not in defense of their own kin but in defense of the Lord. In His name, they prove themselves perfectly willing to kill their own brothers. Remarkably, their fratricidal conduct on God’s behalf later entitles them as priests to mediate between the people and the Lord.

Moses’ instruction to the Levite volunteers is chilling. He puts the death-dealing words, which are surely of his own devising, into the mouth of “the Lord, the God of Israel.” In God’s name, he orders them to engage in wholesale (and, it seems, random) slaughter throughout the camp, “to and fro from gate to gate.” When specifying whom to slay, he does not speak about the guilty but about brothers, companions, neighbors. He orders every Levite to practice fratricide.

At the end of the day, 3,000 men lie slain. Who were they? Traditional exegetes, eager to see only justice at work, have taught that the righteous Levites killed only the guiltiest Israelites, the ringleaders of the rebellion—people whom they would have identified during the celebrations or perhaps those whose guilt was “revealed” by their response to the “ordeal” of drinking the ashes of the idol. But this distinction is nowhere in the text. There is no reason to believe, from the description of the licentious celebration, that there were any innocent among the guilty. And Moses, in instructing the Levites about the killing, does not distinguish between “guilty” and “innocent.” Neither does he—either in his own name or in the words he attributes to the Lord—speak at all about doing justice. It is possible that the Levites did know from the start who most deserved to die; it is also possible, once the fighting began, that they might fairly ascribe guilt—and continued opposition to the Lord—to any persons who took up arms against them; it is even possible to ascribe guilt to everyone who did not answer Moses’ call, “Who is for the Lord?”

Such speculations aside, the plain text makes it appear that the killings by the Levites are less a matter of justice and more a matter of cleansing and purgation—requiring sacrificial victims as the necessary means of purification—and of frightening the many into obedience by making an example of the few. Moses and the Levites administer shock therapy to the body politic, excising a diseased part to save the whole, allowing the “patient” to go into remission (but, alas, never to be cured).

At the end of the day, the killing over, Moses speaks words of comfort to the Levites who have kindred blood on their hands. The enigmatic expression he uses—“They filled your hands to the Lord”—echoes the phrase for installing the priests in the plan God gave Moses for the Tabernacle (“and you shall fill their hand,” u-milleyta et-yadam; 28:41). Your sacrificial deeds, Moses may be telling them, have consecrated you unto the Lord; they have installed you as His priests (in place of the firstborn). Or, if the translation should be read as imperative, “Fill your hands to the Lord,” perhaps Moses is encouraging them now to give new sacrifices to the Lord, to install themselves by making atonement for their fratricide and child slaughter. Either way, Moses holds out to the Levites the prospect that the Lord will bless them for their deeds this day.

Despite all these ambiguities, the big picture is clear: Moses’ action, with the help of the Levites, is a most impressive and successful—albeit horrifying—act of leadership in perilous times. By dividing and purging the people via a small civil war, he reunites them, all in the name of the Lord. He clearly establishes the sin of idolatry and makes visible its terrible consequences. Acting as the Lord’s (self-appointed) fury, he not only reinstitutes his own command over the newly contrite people. As a result of the manner in which he reconstituted the community, he now also “owns” these people, even as they continue to be the Lord’s: having spared and purified them by bloodshed, Moses acquires and accepts full responsibility for their future well-being—exactly as the Lord hoped he would. He also has gained bold and effective fighters who can help him keep order in the future, especially when he again ascends the mountain to speak with God. By making sure that the Levites remember for Whom they have been fighting, Moses redirects them toward the Lord, explicitly affirming the principle that zeal for the Lord’s honor is higher than the love of one’s own kith and kin. A remarkable set of accomplishments for a man who, for the first time, is not merely carrying out divine orders but giving them.

And yet, disquiet hovers over this story. The division of the camp and the selective (or random) killings may have been necessary, if there was to be any hope of preserving the entire people and bringing them back into alignment with the Lord. The reestablishment of Moses’ authority through force may have been equally necessary. But in the renewal of the people as a people, the long-dreaded political iniquity of fratricide is not avoided; on the contrary, Moses pointedly insisted on it in his instructions, which he even attributes (without warrant) to the Lord. He incurs no blame for his deeds here, and his strategy proves successful: when he next goes up the mountain, there will be no rebellion, no orgies, no idolatry. Nevertheless, Moses’ deeds cast a lingering stain of iniquity—the original iniquity, Cain’s slaying of brother Abel—over the entire people and over his own new regime. It is to the Torah’s enormous credit that, unlike Machiavelli, it refuses to treat ugly political deeds as if their necessity could whitewash their ugliness: in somber tones we are told, “And there fell of the people that day three thousand men.” The fratricidal iniquities of Moses’ re-founding will have to be answered for. Fittingly, they will be answered by evils that are unleashed on Moses’ own brother Aaron and his sons, Nadab and Abihu, evils not only linked thematically to the present story but also caused ultimately by the fratricidal implications of Moses’ original unwillingness, at the burning bush, to undertake God’s mission alone.

Thanks to Moses’ action, the political situation in Israel was again, for now, corrected, but in strictly human terms. Yet more is required. The Israelites must now make their peace with God and reknit with Him their fractured relationship.

Excerpted and adapted from Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus by Leon R. Kass. Published by Yale University Press in January 2021. Reproduced by permission.

More about: Aaron, Exodus, Hebrew Bible, Moses, Reading Exodus with Leon Kass, Religion & Holidays