Some of the most interesting and creative work in the field of Jewish studies today is happening neither in universities nor as part of a yeshiva curriculum. Instead, there is a growing space for scholars who don’t quite follow the strict rules of either type of institution.

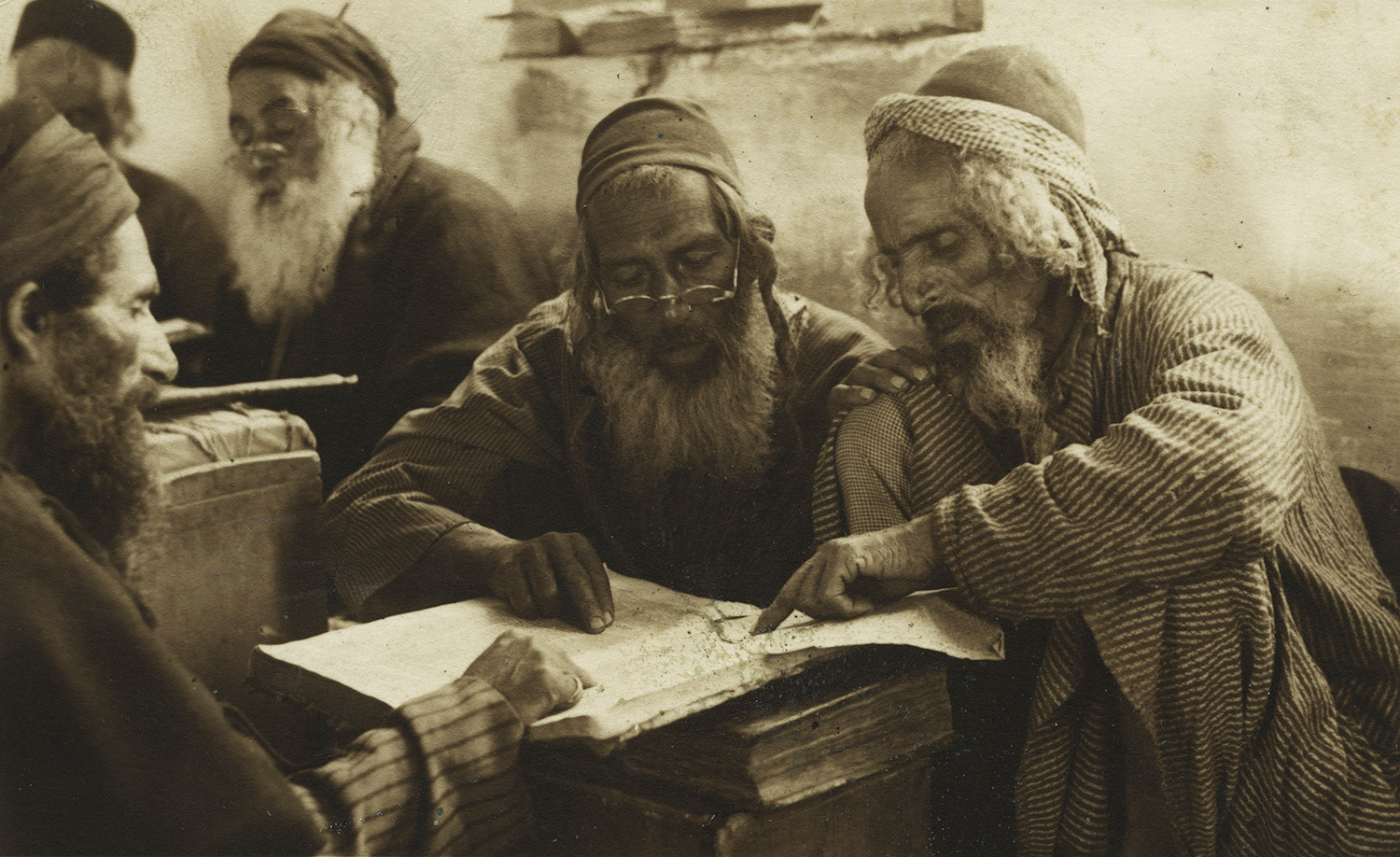

In ḥaredi (sometimes called “ultra-Orthodox”) boys’ education, one subject of study alone is paramount: Talmud. This is especially true in “yeshivish”—that is, ḥaredi but not ḥasidic—male educational environments, where Talmud study is the central religious pursuit around which nearly all service of God revolves. Boys first begin Talmud study at age nine or ten. Once they reach high school, and for many years thereafter, yeshivish men spend nearly all of their time studying Talmud in a central hall called a beit midrash. The daily schedule is organized around three central s’darim (periods), in which everyone studies the same tractate page by page, from early in the morning until late in the evening.

Strictly speaking, the Babylonian Talmud is the massive collection of laws, teachings, and stories that forms the backbone of rabbinic Judaism. But for ḥaredi Jews, “Talmud” extends far beyond the text itself, to encompass numerous other works that are studied alongside it: backwards to earlier compilations such as the Mishnah and Tosefta, as well as the Hebrew Bible itself; forward through the dense forest of medieval and modern commentaries that elucidate and expand upon the Talmud; and outwards to legal codes and responsa, ethical works, and even philosophy. “Talmud” also sometimes extends sideways to roughly contemporary works, such as the Jerusalem Talmud (an earlier version compiled in the Land of Israel) and midrash (collections of rabbinic stories, interpretations, and teachings).

Rather than take distinct classes on particular subjects, a yeshiva’s entire student body ploughs its way together through whichever talmudic tractate is assigned in a given semester, drawing liberally from the entire apparatus of related literature in the process. More advanced students will study in greater depth, usually with more commentaries, while the less advanced focus on getting a basic understanding of the Talmud’s arguments.

The intellectual breadth of this course of study is mindboggling. So is its depth. Complex, multilayered arguments pile upon one another, as subtle nuances in textual wording merge with abstract conceptual categories, and concrete physical realities butt up against scriptural prooftexts. And all of this is accomplished using untranslated Hebrew and Aramaic texts.

Yet for all its intellectual fireworks, in some respects yeshiva study is very rigid. After all, religious study is a sacred act. You don’t need to be particularly drawn to the topic you’re studying because, as students first learn in the Talmud’s Tractate Peah: “Talmud Torah k’neged kulam”—the study of Torah is equivalent to all other commandments. This principle is fundamental to yeshivish life, and yeshiva students devote countless hours to the Talmud because they believe God commanded them to do so. Whatever social and cultural forces underpin this religious belief, as expressed by those who engage with it, it is Torah study purely for the sake of serving God, Torah li-shmah.

Three s’darim a day, every day the same, every day in sync, studying the current tractate, all the while maintaining a proper reverence for the holy text, the holy study hall, and the holy work of Torah (really Talmud) study.

I kind of hated this system.

In my ḥasidic elementary school, religious studies were conducted entirely in Yiddish, while my yeshivish high school taught in English. But the structure was rooted in the same principle: study as a holy endeavor.

My mind bounced around too much to appreciate the systematic rigor of the linear curriculum. My fourth-grade rebbe (religious teacher) wrote on my report card, “a gemara kop [literally, a head for Talmud], but Moishy has to do better keeping his finger oyf’n plats [on the place].” In other words, while I might be good at talmudic reasoning, I needed to learn to follow along in the text with the rest of the class.

But while I loved getting into detailed arguments about the meaning of a talmudic passage, or trying to figure out the intricate logic of the Tosafot (a medieval French commentary), I was also—though I didn’t realize it at the time—often uninterested in the content. I had no reason to be interested, since it was simply whatever the yeshiva said we should learn next, whether this was torts and property law, punishments for false witnesses, the details of marriage contracts, or the order of sacrifices in the Temple. And regardless of the content, the mode of study remained the same: the same foundational assumptions, the same sorts of questions and problems, and the same commentaries, approached in roughly the same order.

As an adult I have chosen a different path of Talmud study, and have found kindred spirits in unexpected places.

The periodical Ḥakirah bills itself as the “Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and Thought.” Flatbush is an Orthodox neighborhood in Brooklyn that is—perhaps uncharitably—known more for its materialism than its intellectualism. But despite my initial skepticism, in Ḥakirah one finds Torah that is—in some respects—quite different from that found in the beit midrash, but no less vibrant.

Ḥakirah is physically arranged like an academic product—a humanities journal, complete with footnotes and citations. Yet its underlying worldview is not that of the academy; it’s a religious journal covering religious topics and questions.

But that’s what makes this journal’s content so different from yeshiva study: it covers questions, not Talmud pages. Do you want to know what the rabbinic perspective on aliens is? Volume 27 will fill you in with “A Study on the Rabbinic Perspective on Life and Living beyond Earth.” What about complete body-hair removal for men? Volume 29 discusses “Male Body-Hair Depilation in Jewish Law.” Of course, the journal covers more serious and traditional topics too, such as the Jewish laws of mourning, or the proper liturgy during the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. But often these are not written by rabbis, yeshiva students, or academics, but by lay enthusiasts. For example:

- “BRCA Testing for All Ashkenazi Women: A Halakhic Inquiry”

Bio: Sharon Galper Grossman, MD, MPh, is a radiation oncologist and former faculty member of Harvard Medical School, where she also obtained a master’s in public health. - “Between the Stōïkos and the Beth Midrash: A Philosophic and Ethical Comparative Analysis of Stoicism and Judaism”

Bio: Stewart Rubin, a real-estate professional, enjoys studying the intersection of anthropology, archaeology, history, philosophy, sociology, and religion. - “Hoshanos: Changing a Community Custom”

Bio: Dr. Steven Oppenheimer is an endodontist and has published articles on various halakhic issues.

Nearly every volume of Ḥakirah features articles by both academics and rabbis, but also by people like Dr. William Gewirtz, a former CTO of AT&T Business, or the trio of authors (writing on the monetary value of tall stature!) who work at the MIT Auto-ID and Field Intelligence Laboratories.

In all these cases ordinary people found something interesting, exciting, or otherwise compelling in the vast sea of Jewish literature, put pen to paper, and shared their Torah with others.

The type of Torah study that produces articles in Ḥakirah is not usually the three-period-a-day Torah of the yeshiva, but that of the guy in his pajamas who can’t quite put away his books at two in the morning. It’s not driven solely by a drive to serve God, but also (perhaps even primarily) by the engagement and excitement of finding something new and interesting. One can’t quite say it’s purely li-shmah—for the sake of heaven—because the people who write these articles are getting too much personal pleasure out of it.

Torah study in the beit midrash can sometimes be too holy—cordoned off from everyday life in ritualistic formal dignity. But those who take their Torah outside of the confines of the yeshiva are anything but formal; they are found leaning against bookshelves absentmindedly thinking for hours, missing their subway stops immersed in an idea, or finding themselves ordering way too many books because they simply must know what the latest volume has to say on a topic.

These are also the sorts of people who find their way to Nachi Weinstein’s popular SeforimChatter podcast. Weinstein, a law student and resident of Lakewood, New Jersey—a yeshivish enclave centered around America’s largest yeshiva, Beth Medrash Govoha—is a long-serving librarian of seforim (religious books) in his grandfather’s synagogue. Somehow, the job slipped its way into his soul, and these books became his passion. He started examining critical editions, became interested in Jewish history, and started a twitter feed that announced the release of both new seforim and academic works in Jewish studies.

To understand the podcast’s appeal, you have to understand Weinstein’s tremendous breadth of knowledge, along with the unusual mix of people who come on his show.

These guests tend to have more standard scholarly credentials, whether academic or religious, than those who publish in Ḥakirah. Well-known and lesser-known academics come on to discuss their work: recent guests include Robert Brody speaking about the rabbis of medieval Iraq, Magda Teter on the history of the blood libel, Lawrence Schiffman on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Elisheva Carlebach on Jewish communal registers in early modern Europe, and Marcin Wodzinski on Ḥasidism. Weinstein also invites rabbis who have spent their lives within the ḥaredi world. He’s interviewed Rabbi Aaron Lopiansky, head of a major yeshiva in Washington, DC; Rabbi Yehoshua Hartman, who edited the most recent editions of the writings of the 16th-century scholar and mystic Judah Loew ben Bezalel of Prague (a/k/a the Maharal); Rabbi Nechemya Sheinfeld, who edited and wrote a super-commentary on the biblical commentary of the 12th-century Spanish sage Abraham Ibn Ezra; and Rabbi Moshe Kravetz, who has edited many of the works of the Renaissance Italian rabbi Obadiah Sforno.

Weinstein is also remarkably ecumenical. Playing against the stereotype of a cloistered, sexist, and intolerant ḥaredi world, he interviews almost as many women as men, non-Jews as well as Jews, and academics and rabbis whose perspectives are far from normative within ḥaredi society. The very existence of his podcast, as well as its popularity, unsettles some basic assumptions about ḥaredi culture.

Although his interview style keeps him in the background most of the time, letting his subjects present their work, when he does jump in he displays impressive erudition, both about the subject at hand and the history of the books that relate to it. He’ll often point to obscure editions of texts that the interviewees aren’t aware of, or to tangential works that have just been published or reissued, enlightening both the audience and the expert being interviewed.

In between the academics and the Ḥaredim, however, SeforimChatter features many of the same sorts of enthusiasts whose work fills the pages of Ḥakirah. Mitchell First, a lawyer who wrote a historical study of the book of Esther, described how an initial article of his was rejected by Ḥakirah, at which point someone suggested he try the AJS Review, a premier academic Jewish-studies journal—which accepted it. Steve Weiss, a doctor in Los Angeles who owns the world’s largest collection of commentaries to Pirkei Avot (a talmudic tractate dealing with ethics), discussed his just-published bibliography of everything written on the subject (you can apparently get a free copy by emailing [email protected]). Yossel Housman, who works for Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha (and tweets prolifically using the handle @yeshevav), has visited the podcast to discuss the history of Ḥasidism, as well as the origin of the Tisha b’Av lamentations.

What links the vast majority of guests on the SeforimChatter podcast with one another, as well as with the writers at Ḥakirah, is the story of how they began researching their respective topics of interest. Listening to their accounts is like listening to someone describe a romance: first falling in love and then developing a deep connection to the topic they’re drawn to.

Rabbi Housman describes himself chancing upon a religious book one day while perusing the synagogue bookshelves, and reading about the workings of Sephardi liturgical poetry (piyyutim). These poems tend to employ complex metrical and rhyme schemes, are highly allusive, and often use deliberately arcane language; they are rarely, if ever, studied formally as part of a yeshiva curriculum.

He was immediately fascinated, and as he started to read more on the subject, he wandered into a ḥaredi bookstore asking for books about Solomon Ibn Gabirol, one of the genre’s greatest practitioners. The shopkeeper had no idea how to help him, but a passerby overheard their conversation and took an almost proprietary affront at a novice making such an inquiry: “why do you want to know this?” When the stranger (neither an academic nor a rabbi) was convinced Rabbi Housman was worthy of the subject, he took his number and called him later that night to give him an hour-long introduction to the field. At that point Housman was clearly smitten—he describes the aesthetic beauty of some piyyutim; the meter, the rhymes, the wordplay; the sophisticated subject matter; the biblical, talmudic, and midrashic references; and the joy of solving the riddles and puzzles in each line.

The serendipitous beginnings to these love stories repeat themselves in nearly every episode of the podcast. Weiss describes buying a shelf of seforim on Pirkei Avot from a store on the Lower East Side in the 1970s. Rabbi Hartman describes walking into the office of the eminent sage, Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner, and offering an explanation of the Hanukkah story that led to Hutner yelling at him that his explanation was complete nonsense, and that if he wanted to understand the holiday properly he should consult the writings of the Maharal. Robert Brody obliquely refers to the fact that he was a math prodigy as a young man (“I got a bit of a way down that track . . .”), but got interested enough in rabbinic literature to switch fields. Puzzled by the absence of information on the geonim—the chief rabbis of Iraqi Jewry in the early medieval period—he started researching them. Now a professor at Hebrew University, he is the world’s leading authority on the subject.

A standard SeforimChatter origin story begins with a question or puzzle, a chance encounter, or the explicit realization of love at first sight that blossoms into a mature and enduring relationship with the subject. As Professor Shalom Sabar explains, in describing his work on Jewish illuminated manuscripts, which grew out of a course of doctoral study originally focused on medieval Christian art: “I got an offer to work at the Jewish museum in Los Angeles, the Skirball Museum. . . . I fell in love with the k’tubah [marriage contract] collection, and since then I’m in Jewish art.”

A common trope in stories and biographies of great rabbis that have become popular among contemporary Ḥaredim is that these sages thought about Torah every second of the day. This is a lot less impressive to me now that I pursue study of Torah she-lo li-shmah, not (only) for the sake of heaven, but for the love of the subject itself. Now, the idea of thinking about the study I love at all times is obvious and banal.

“He had to force himself to stop thinking about Torah in the bathroom!” these hagiographies frequently exclaim, referring to the prohibition on contemplating sacred matters in the toilet.

So?

Who wouldn’t? If you really love Torah, of course you have to make a conscious effort to stop thinking about it. Otherwise, as with all objects of love, your mind will continue to whirl, wrapped up in every detail. Torah study that works its way into your life is with you in every part of life, and if you want to keep it out of the bathroom, it’s going to take effort.

None of this to say that the yeshiva, with all of its structure and formality, doesn’t breed this type of love. It does, and often. Walk into any beit midrash at any time of day or night and you will find people puzzling through their projects, wrestling with some problem they can neither solve nor let go, and enthusiastically arguing with their study partners about the meaning of a passage. For some, the entire edifice of Torah study is itself an object of love; for others, every new topic (whatever it may be) is a new pleasure.

But this is not usually the type of love that produces an article in Ḥakirah or a visit to SeforimChatter. For that the yeshiva student has to encounter something that grabs him (and unlike in Ḥakirah or on SeforimChatter, it is always “him”): “Why hasn’t anyone written about this?” “Why doesn’t anyone recognize this fundamental mistake in the logic of this passage?” or even “what is the application of this view to the potential existence of aliens?”

The culture of scholarship developed by the yeshiva system, rigid as it may be, produces a society that is peppered with hidden scholars: accountants, lawyers, and businessmen, who may have day jobs, but whose internal life is wrapped up in their own personal pursuit of Torah. It remains a source of great amazement to me, even after all these years, to see just how incredibly learned yeshiva graduates can be. Sometimes, this learning is simply a product of cultural norms, and remains secondary to their professional, personal, and religious lives, but frequently it is more than that: it is the product of a passion that they just couldn’t let go of.

Critics of ḥaredi yeshivas often disparage universal Talmud study as economically unsustainable, historically inauthentic, and a waste of time for all but the very top students.

Perhaps.

But the yeshiva also creates the environment in which individuals can encounter something worth investigating, something they can explore, understand, and make their own. Paradoxically, it is the very structure and rigidity of the yeshiva curriculum—driven by the belief that studying Talmud all day and every day is the holy work that Judaism demands—that produces an army of self-directed secret scholars, often using serious academic techniques, pursuing topics of interest in Judaism.

The yeshiva system that asks all students to pursue Torah li-shmah full time is a product of our modern age. It’s just one mode among others that Orthodox Jewish communities use to negotiate a world that does not share their underlying assumptions about reality or the purpose of life. Ḥasidic Jews have their own strategies, as do the non-ḥaredi Orthodox. And like all attempts to maintain a religious culture in a secular world, this approach has strengths and weaknesses. There will always be kids who just can’t keep their fingers “on the place.” Yet, even for students who follow the curriculum meticulously, who are paragons of Torah for its own sake, yeshiva education will still support independent exploration—as long as they get comfortable enough not to treat the material as too holy to touch.

Through the rigorous and in-depth study facilitated by the beit midrash, students are exposed to a tremendous amount of pure Torah content, and they explore it to its greatest depths; it is inevitable that many of them will, at some point in their study, stumble over something that stops them in their tracks and takes their breath away. “Now that’s interesting . . . ”

You might even say that the greatest virtue of the yeshiva system is that it turns a classic talmudic aphorism on its head. While the Talmud states that one should study Torah even not for its own sake—she-lo li-shmah—because doing so will ultimately lead to study that is li-shmah, the yeshiva system may achieve something of even higher value: from study li-shmah one may come to she-lo li-shmah, via Torah for the sake of Heaven I might achieve Torah for my own sake.

More about: Jewish education, Jewish studies, Religion & Holidays, Talmud, Yeshiva