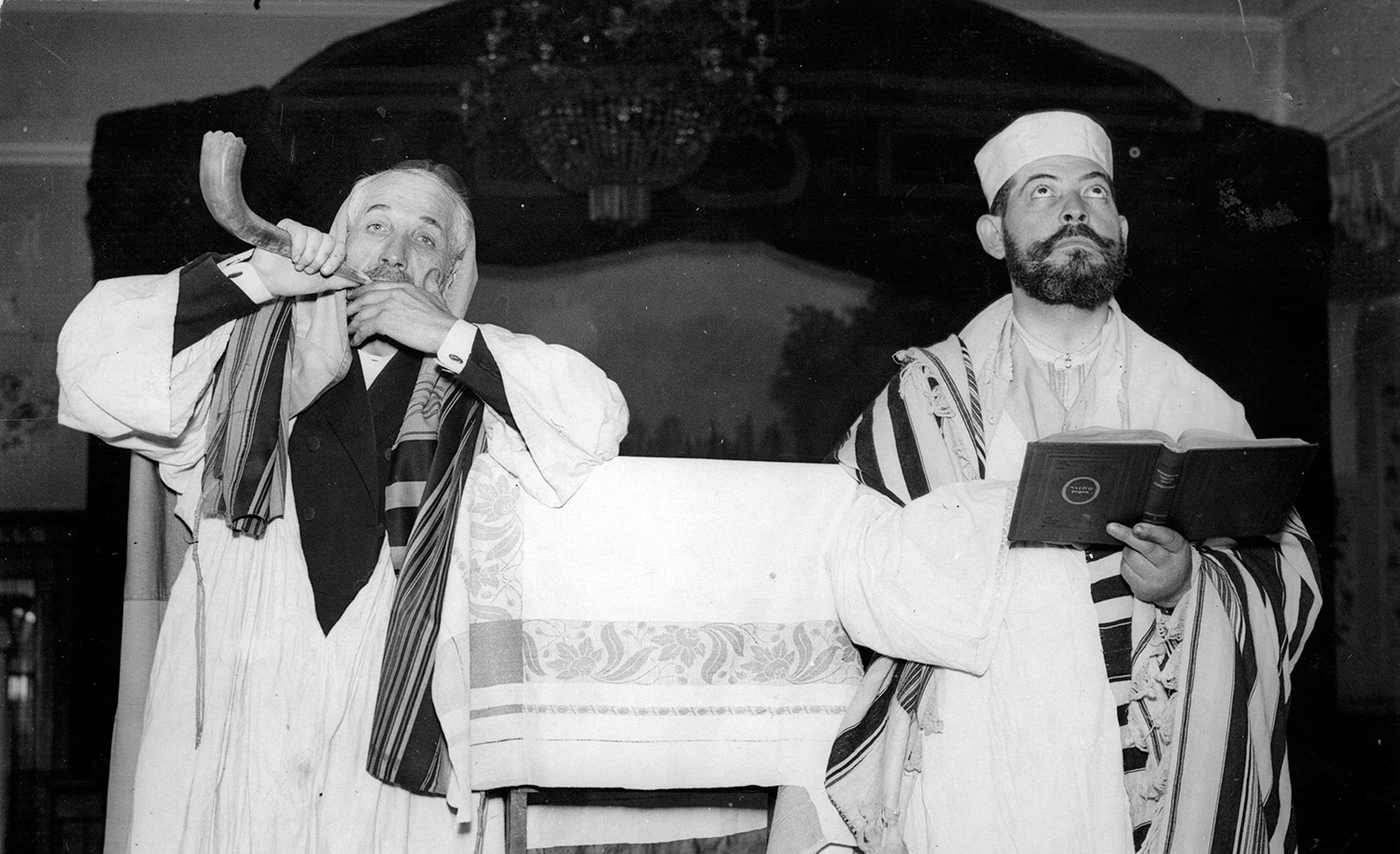

A rabbi with his shofar on Yom Kippur on September 23th, 1930. Imagno/Getty Images.

Kol Nidrei is so well-known a prayer, and so powerful when performed cantorially, that few who hear it in its traditional Ashkenazi version, which is the one nearly all American Jews are familiar with, are aware of its self-contradictions—all the more so because, apart from a single phrase in Hebrew, it is entirely in Aramaic and the English translations that accompany it in most siddurim attempt to paper these over. Here are four versions of its opening lines: the first the standard Ashkenazi text transliterated in Latin characters; the second an English translation in Chabad’s Annotated Machzor for the High Holidays; the third the translation of the Conservative movement’s Mahzor Lev Shalem; and the last a literal English rendition of my own. (Words originally in Hebrew are indicated by bold print.)

1) Kol nidrey v’esarey ushvu’ey v’ḥaramey v’konamey v’kinusey v’khinuyey d’indarna ud’ishtabana ud’aḥarimna ud’asarna al nafshatana miyom kippurim zeh ad yom kippurim haba aleynu l’tovah, bi-khulhon aḥaratna v’hon.

2) All vows, [self-imposed] prohibitions, oaths, consecrations, restrictions, or [any other] equivalent expression of vows, which I may vow, swear, dedicate [for sacred use] or which I may proscribe for myself or for others, from this Yom Kippur until the next Yom Kippur which comes to us for good, we regret them all.

3) All vows, renunciations, bans, oaths, formulas of obligation, pledges and promises that we vow or promise to ourselves and to God from this Yom Kippur to the next—may it approach us for the good—we hereby retract.

4) All vows, prohibitions, oaths, bans, renunciations, penalties, or invocations of the divine by which we have vowed, sworn, renounced, or foresworn anything from this Yom Kippur to an auspicious next Yom Kippur, we repent of them all.

Ignoring minor differences of wording, we see that Versions 1 and 4 differ from Versions 2 and 3 in a significant respect: namely, their use of the past tense (d’indarna, ud’ishtaba’na. ud’aḥarimna, ud’asarna—“by which we have vowed, sworn, renounced, or foresworn”) for unfulfilled commitments that are referred to as taking place in the future (“from this Yom Kippur to next Yom Kippur”). Versions 2 and 3 seek to eliminate this odd feature by translating the past tense either as a conditional (“which I may vow . . .”) or a present tense (“that we vow . . .”), thus leaving the reader with a false impression of internal consistency.

Explaining Kol Nidrei’s contradictory nature calls for delving into its history. The prayer, whose author is unknown, dates to the 9th century CE, when a majority of the world’s Jews lived in the Aramaic-speaking Middle East, most concentratedly in Babylonia. Originally worded not “from this Yom Kippur to next Yom Kippur” but “from last Yom Kippur to this Yom Kippur,” it referred to unfulfilled vows and promises made in the course of the previous year, its purpose being to absolve the congregants of the punishment they would be sentenced to on the Day of Judgment for not honoring their word. The geonim, the religious heads of Babylonian Jewry, did not look favorably on this addition to the liturgy. The renowned talmudic scholar Hai Gaon (939-1038) called it a “foolish custom that is not to be followed,” and his successors shared his view that a vow that had been made could be rescinded only by a special rabbinic court, not by a liturgical declaration.

Yet the “foolish custom” of Kol Nidrei persisted despite such opposition, presumably because the fear of God’s justice was greater than that of the geonim’s disapproval, and the prayer spread to other parts of the Jewish world, including southern and central Europe. Here, too, it met with the resistance of the rabbis—some of whom, however, realizing that it had become too entrenched to be uprooted, decided to change rather than eliminate it. The leader in this was the noted talmudic scholar Jacob ben Meir (ca. 1100-1171), better known to tradition as Rabbeinu Tam, who decreed that Kol Nidrei’s wording be altered from “from last Yom Kippur to this Yom Kippur” to “from this Yom Kippur to next Yom Kippur.” His reasoning was that while it was impermissible to cancel a vow that had been made, it was legitimate to pray for the cancelation of a future one, since this was merely the expression of a wish.

Rabbenu Tam lived in northern France, which lay within the Ashkenazi sphere of influence, and his ruling, though widely accepted there, drew fire from elsewhere, as from the Catalonian rabbi Yitzḥak ben Sheshet (1326-1408), who wrote: “Even if Kol Nidrei refers to the future, it is better not to recite it in order to keep vows from being taken lightly.” Gradually, though, the new wording was adopted by most Jewish communities, spreading from Ashkenazi lands to Sephardi and Mizraḥi or Middle Eastern ones. And yet oddly enough, this happened without changing the Aramaic verbs, which remained in the past tense, perhaps because they were by now so sanctified by tradition that no one wanted to tamper with them.

At the same time, however, in some communities, particularly in North Africa and the Middle East, the illogic of using past-tense verbs for a future situation was deemed unacceptable. A solution was sought—but the twofold one hit upon, while making sense grammatically, made none at all in terms of Rabbeinu Tam’s objection. This was, on the one hand, to justify the past tense by restoring the old formula of “from last Yom Kippur to this Yom Kippur” alongside the new one, which by now had the weight of tradition too, so that the text of Kol Nidrei became, “From last Yom Kippur to this Yom Kippur and from this Yom Kippur to next Yom Kippur”; and on the other hand, to provide each past-tense verb with its future-tense complement, so that the Aramaic now read d’nadarna ud’nindar, d’ishtabana ud’nishtaba, “by which we have vowed and will vow, by which we have sworn and will swear,” etc.

Such phrasing has survived in many Sephardi and Mizraḥi communities to this day at the same time that it has been rejected by others, such as Yemenite and Central Asian Jewry. And strangely, too, while some Ashkenazi congregations also adopted the wording of “From last om Kippur to this Yom Kippur and from this Yom Kippur to next Yom Kippur,” they did not conjoin future verbs to the past ones, so that they ended up being both grammatically illogical and flouting Rabbeinu Tam’s ruling!

The historical outcome of all this has been different versions of Kol Nidrei of which none meet the double requirement of both logic and compliance with Rabbeinu Tam’s ruling. Indeed, since this coming Tuesday night most but not all Sephardim and Mizraḥim will be asking to have their unfulfilled vows and promises canceled for both 5782 and 5783, while most but not all Ashkenazim will be petitioning in the wrong tense for 5783 alone, even God might be bewildered. Perhaps we should learn to keep the promises we make and avoid all the confusion.