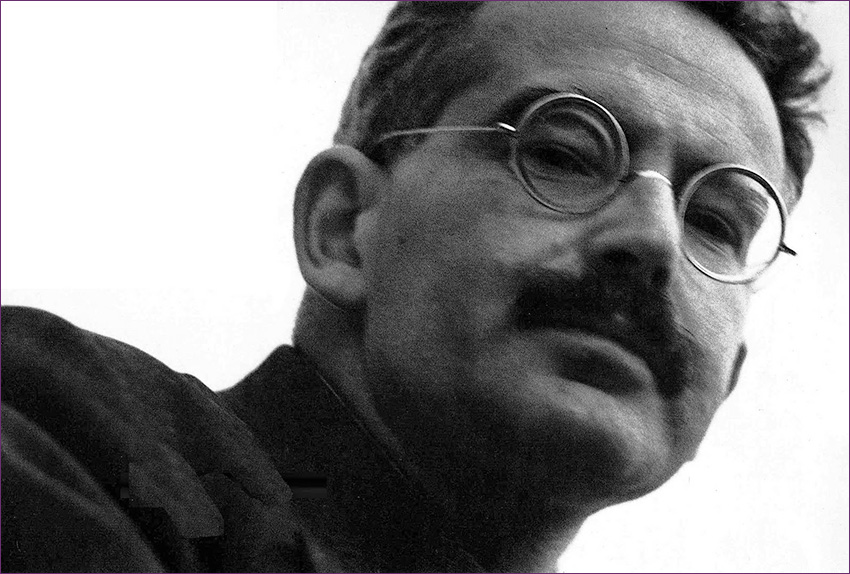

The German Jewish intellectual Walter Benjamin, born in Berlin in 1892, dead by his own hand on the French-Spanish border in 1940, remains a man of mystery. Anything but prominent in his lifetime, he has emerged in recent decades to unvarnished acclaim as the greatest thinker of the 20th century in fields ranging from philosophy to sociology, aesthetics, literary theory and criticism, and a half-dozen more. This in itself is mysterious. Among the ranks of mid-century Central European intellectuals, the reputation of Benjamin’s contemporaries and colleagues (with the possible exception of the Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno) continues to shrink; his continues to rise and rise. The number of books and articles devoted to him is staggering; a huge new biography, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, co-written by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings and published by Harvard, is only the latest addition to a seemingly unending stream.

How to explain the Benjamin vogue? Eiland and Jennings cite such cultural signposts as the radical student movement of the 1960s and the attendant revival of Marxist thought. But 60s radicals were hardly great readers, and Benjamin’s writings are, to say the least, maddeningly opaque and often altogether inaccessible. As for his Marxism, such as it was: if that is the main point of attraction, by rights the real culture hero should be his contemporary Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979)—once famed as the “father of the New Left” but, these days, decidedly not a name to conjure with.

More likely, Benjamin owes his fame to the rise of cultural studies and its various academic subdisciplines: post-modernism, post-structuralism, women’s and gender studies, and the rest of the lot. In these precincts, Benjamin’s gnomic style may well count as a plus, an outward sign of inward profundity that, simultaneously, invites the most fanciful flights of interpretive ingenuity. Likewise contributing powerfully to his allure is the sorry story of his life. Quite apart from his tragic end—he swallowed poison while fleeing from Nazi-occupied France—he was always the frustrated outsider par excellence, the very type of the marginal man. Indeed, had he lived, one can hardly picture him as a happy soldier among the academic janissaries of contemporary cultural studies.

My own interest in Benjamin arose from my work in the early 1950s on the pre-World War I German youth movement, in which he had been a passionate but by no means leading member. In connection with this project I met some friends of his youth, including, in Germany, the pioneering educator Gustav Wyneken, who had served as one of his early gurus. In Italy, I encountered a number of his former associates in the radical youth journal Der Anfang. In Jerusalem there lived the librarian and poet Werner Kraft, an early friend but later a critic, and above all Gershom Scholem, who had been Benjamin’s closest friend both in Berlin and later on and who would become, with Adorno, the figure most responsible for launching his posthumous reputation.

The Scholems’ living room in Jerusalem was dominated by a drawing—Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920)—which had been owned by Benjamin and played a central role in his thinking, and which Scholem had inherited after the war. (It is now in the collection of the Israel Museum.) At tea in the Scholem household, sooner or later, the conversation would turn to the Benjamin Question. Yes, he was highly educated, widely read, and engaged in diverse areas of inquiry. Yes, his ideas (as in his best-known essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”) were often original, and there were flashes of genius. But in what precisely did his genius consist? Had he produced a new philosophy of history, proposed a fundamentally new approach to our understanding of 19th-century European culture, his main area of concern, or revolutionized our thinking about modernity? The answers I received weren’t persuasive then, and the answers provided in the vast secondary literature of the last decades have done no better.

To some, the problem is simply that most of Benjamin’s major work remained unfinished. I refer above all to his monumental Arcades Project, inspired in part by an abiding obsession with the urban poetry of Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867). The arcades in question were the glass-enclosed passages in central Paris when that city was, in Benjamin’s terms, the capital of the 19th century. A central emblematic figure for Benjamin was that of the flâneur, the stroller or urban explorer who habituated these environs. Having gathered a mountain of materials, Baudelaire’s poetic masterwork Les Fleurs du Mal being prominent among them, Benjamin wanted to show how urbanization had revolutionized not only culture, as evidenced in art and architecture, urban planning, and new ideas of beauty, but life in general. Traditional critical approaches, whether historiographical or philosophical, were, he pronounced, inadequate to grasp this new epoch of high capitalism and what it had wrought. A new, Marxist-tinged “materialist” theory was needed; he, Benjamin, would provide it.

Did he? Apologists point to the impediments that beset him at every stage of his career. Even his “habilitation”—the major piece of scholarship, in addition to the doctoral dissertation, that had to be submitted by anyone hoping for an academic career—had been rejected. Later, his plans to establish a new journal with the playwright Bertolt Brecht came to nothing. He never held a permanent job, regarding it as the duty of his family and his estranged wife to support him. After 1933, there were handouts from Adorno’s Frankfurt School, which had wisely transferred its funds to Switzerland and later to America, but this was no substitute for a steady source of income.

But let us assume that he’d succeeded in finishing his great project. Wherein lay its originality? The figure of the flâneur had been “discovered” earlier in the novels of Honoré de Balzac and others, and the main themes of Baudelaire’s poems had been studied even by German academics, some of whom had offered analyses not dissimilar to Benjamin’s. Were the Parisian arcades, with or without Baudelaire, the right starting point for a new understanding of modernity? Even the most detailed Benjamin biography, by the distinguished French professor Jean Michel Palmier, reaches no satisfying conclusion on this point. (Palmier’s mammoth book, almost 1,400 pages long, remains, like Benjamin’s work, unfinished—which is a comment in itself.)

It is much easier to write the life of a man of action than to write about a thinker, and Benjamin was nothing if not a man of inaction; in view of the difficulties this poses to a biographer, Eiland and Jennings deserve much praise. By necessity, their book is based mainly on Benjamin’s essays and correspondence. Admirably comprehensive as it is, however, there are also some strange omissions. Notably underrepresented is Asja Lācis, Benjamin’s great love; it was she who broke up his marriage, was instrumental in his conversion to a peculiar brand of Marxism, and engineered his personal introduction to Brecht. Latvian-born, a militant Communist, she lived in Moscow until suddenly disappearing in 1938. Although Benjamin must have known that she had been sent to a gulag (where she spent the next ten years), and although losing her must have had a major impact on his life and work, there’s barely* a word about this aspect of things in the Eiland-Jennings book—probably because it does not figure in his correspondence.

Since Benjamin’s death in 1940, two issues in particular have been endlessly debated: the nature of his Marxism and his attitude to Judaism. From the 30s onward, he thought of himself as a Marxist, and so he is regarded by others among his many admirers. But Scholem, who from the beginning considered Benjamin’s “materialist” orientation not only wrong but deluded—hard as he might try, Benjamin would never be able to transform himself into a materialist—dismissed this description of him as a misunderstanding. Similarly skeptical was Max Horkheimer, the leading figure in the Frankfurt School, who called Benjamin a mystic; as for Brecht, his denunciations of Benjamin’s mystical aberrations were especially harsh. More recently, the literary theorist Terry Eagleton has dubbed him a rabbi.

The confusion over Benjamin’s politics is easily explained. Of all the Weimar intellectuals and eventual emigrants, he was perhaps the least politically minded. Reading his essays and correspondence from the 30s, one cannot fail to be struck by the breadth of his interests and the depth of his knowledge—and the almost complete dearth of anything on politics. As the world was going up in flames, Benjamin was writing about the motifs of Baudelaire’s poetry. Of course he hated the Nazis and all they stood for, but I doubt he read much or anything by Marx except for the newspaper dispatches collected in The Class Struggles in France, for the light they shed on the Paris scene in the mid-19th century. As for his enduring devotion to Baudelaire, an arch-reactionary whose guru was Joseph de Maistre, a sworn enemy of the French Revolution, one has to look elsewhere than to politics for an explanation. The same goes for his admiration of Proust—hardly an idol of the Left—and his interest in Kafka.

Similar inconsistencies plague any attempt to understand Benjamin’s attitudes toward things Jewish; although this subject has given birth to a small industry, seldom has so much been written about so little. His family background lay in the highly assimilated Berlin Jewish upper-middle class. His deep friendship with the young Scholem did greatly help to stimulate an interest in Judaism—but how deep did it go, and how long did it last? He read Franz Rosenzweig’s The Star of Redemption (1921) not as a theological but as a philosophical text, and in later years it played no role in his thinking; it certainly did not bring him closer to God or to the synagogue.

Scholem, who had moved to Jerusalem in 1923, tried for years to persuade Benjamin to join him at the Hebrew University. He toyed for a while with the idea of a visit or even emigration, but eventually gave it up even though it held out the prospect of an academic career, friendships, and a salary. Esther Leslie, a professor of political aesthetics who admires Benjamin and frowns on Scholem’s attempts to lure him away from Paris, observes that he had no reason to find Zionism, or the desert, appealing. This is quite correct. European culture was infinitely more interesting to him; besides, there were no arcades in Jerusalem, and no keys to modernity in Mea She’arim.

Benjamin’s place was in Europe; unfortunately, Europe had no room for him. The strictures of the professor of political aesthetics aside, had he followed Scholem’s pleas to join him in the “desert”—that is, the verdant and congenial Jerusalem neighborhood of Rehavia—he would have lived another decade or two or perhaps even three. Instead of dying a miserable, self-administered death on the French-Spanish border, he could, had he so wished, have returned to his beloved Paris after the war. I can well imagine him in 1944, sitting in a Rehavia café, discussing philosophy with Natan Rotenstreich or photography with Tim Gidal or physics with Shmuel Sambursky, playing chess with the folklorist Emanuel Olsvanger, and debating with the three Hanses (Jonas on Gnostic religion; Polotsky on linguistics; Lewy on Greek philosophy). Most of these figures belonged to the Pilegesh (“Concubine”) circle of German Jewish intellectuals and scholars presided over by Scholem.

One way or another, Rehavia would have taken care of Benjamin: not the most padded existence, perhaps, and perhaps a little boring after Paris—but a fate worse than panicked suicide in a shabby hotel? The impressive memorial by the sculptor Dani Karavan in the Spanish border town of Port Bou is no compensation.

* Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that there is “not a word” in Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life about Lacis’ internment. It is mentioned on page 321.

__________________

Walter Laqueur is the author of, among other books, Weimar, A History of Terrorism, Fascism: Past, Present, Future, and The Dream that Failed: Reflections on the Soviet Union. His newest book, Optimism in Politics and Other Essays, was published by Transaction in January.