The Sabbath service this week marks the imminent onset of the month of Nisan, in which Passover occurs. Appropriately enough, a special reading from the Torah, harking back to the portion of Bo in the book of Exodus, is added to the week’s regular portion of Vayikra (Leviticus 1:1-5:26). Here I want to concentrate not on the specific verses (Exodus 12:1-20) from Bo that are read, or rather reread, on this Sabbath but on its overall narrative of the unfolding relationship between Pharaoh and the Lord as mediated by the Lord’s instrument Moses.

The central issue of Bo is what is within the body of Egypt, whether the body in question is that of Pharaoh, or the body of the people of Egypt who are an extension of the sovereign’s body, or the body of the land of Egypt. And not only what is within the body but outside it, what belongs and what should be expelled, what will enter without permission and what will finally be released unwillingly, spat out like poison or bile.

The very first verb of the reading is bo, come, and this divine instruction to Moses (“Come unto Pharoah” . . .) uses precisely the same verb that in Genesis instructed Abraham to “come unto” and impregnate Hagar, the barren Sarah’s Egyptian maid. Obviously, I am not suggesting that the Lord instructed Moses to enter Pharaoh physically. But the appearance of that particular verb at this particular juncture alerts us to a whole series of intimate and unjust relationships in the Torah. The series begins with Sarah’s oppression of Hagar, continues with Joseph’s enslavement of all Egypt, rebounds upon the Israelites in Pharaoh’s subsequent enslavement and oppression of them, and enters into its culminating episode here as the Lord instructs Moses to come unto Pharaoh before the Lord Himself will enter into Pharaoh’s most private and intimate space: his mind.

But the Lord said to Moses, “Come unto Pharaoh

For I’ve given him a heavy heart and his servants, too,

To put these marks of Mine in him

And to make you tell your son and grandson how I abused Egypt

And My marks that I put in them, so you’ll know I am the Lord.”

And Moses and Aaron came unto Pharaoh and told him,

“So says the Lord, God of the Hebrews:

‘How long will you refrain from responding in My presence?

Send out my people to worship Me.

For if you refrain from sending My people

I’ll bring locusts over your border

And they’ll cover all visible land,

You won’t be able to see the land.’” . . .And he turned and he left Pharaoh’s presence

And Pharaoh’s servants said to him:

“How long will this ensnare us—

Send the men to worship the Lord their God.

Do you not realize yet, Egypt is lost?”

So Moses returned with Aaron to Pharaoh

And he told them, “Go, worship the Lord your God;

Who’s who that’s going?” And Moses said,

“We’ll go with our boys and old men, with our sons and our daughters,

Our sheep and our cattle we’ll go

For it’s God’s festival for us.”

And he told them, “Let it be so, the Lord be with you when

I send out you and your children—

Look how there’s evil over your face.

Not so; kindly go, just the males, and worship the Lord

Because that’s what you’re asking.”

And Pharaoh drove them out from his presence.

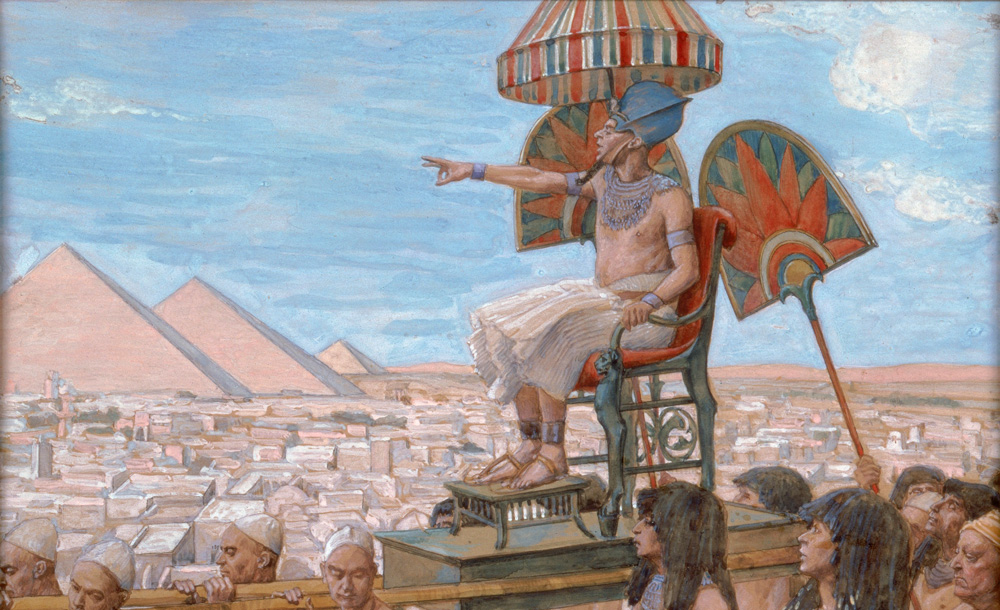

In addition to what you might call the special effects of the ten plagues, which I’ll largely omit here, what’s beguiling in this portion is the acute portrayal of Pharaoh as petulant villain. But he’s not two-dimensional; he’s more than three-dimensional. You can hear the man’s voice as he keeps changing his mind, turning on a dime, arriving almost at the point of cooperating and then withdrawing again like an insecure businessman not quite capable of closing a deal. The irony of his consenting to Moses, swiftly followed by the outburst about how Moses and Aaron are scheming to deceive him, followed by the noblesse-oblige condescension of his polite “request” that the males go without their children, followed finally by the curt dismissal of Moses and Aaron, gives you a Shakespearean portrait in just two or three lines.

And it’s not over.

But Pharaoh was quick to call Moses and Aaron

To say: “I’ve sinned to the Lord your God and you.

But now bear with my sin just this once

And petition the Lord your God to remove from me just this death.”

And he went out from Pharaoh and petitioned the Lord

But the Lord reinforced Pharaoh’s heart

And he didn’t send out the children of Israel.

Rabbis over the centuries have tied themselves in knots to prove that Pharaoh had freedom of choice, free will, that he was able at any point to release the Jews but chose not to. A literal reading of the text shows that this was not the case. Not only does the Lord declare at exactly what point He will allow Pharaoh to come to his senses, He also tells Moses that He’s not interested in Pharaoh’s coming to that point. He wants to pummel Pharaoh into submission, and it does not suit His purposes for Pharaoh to have free choice, let alone to make an intelligent call.

Time and again, the Lord reinforces Pharaoh’s heart. Two different verbs are used for this action, which is often flattened in English translation into a single “hardened Pharaoh’s heart.” On the one hand, He makes Pharaoh anxious, literally makes his heart heavy; on the other hand, He makes him proud—literally strengthens his heart. This is the cycle by means of which a losing hand or two become a total bust. Pharaoh is meant to be left incapable of running a lemonade stand, let alone the mightiest empire on earth.

And Pharaoh called Moses and said, “Go worship the Lord

Just your sheep and cattle will be deposited,

You children can go with you, too.”

But Moses said, “You shall also put sacrifices and offerings in our hands

To make for the Lord our God,

So our livestock will go with us,

Not a hoof will be left behind

For from them we’ll select to worship the Lord our God

And we won’t know how we’ll worship the Lord till we get there.”

But the Lord reinforced Pharaoh’s heart and he balked at sending them

And Pharaoh told him, “Get away from me,

Take good care you don’t see my face again

Because the day you see my face you’ll die.”

And Moses said, “Just as you say. I will not look on your face again.”

And the Lord said to Moses, “One more ache

I’ll bring on Pharaoh and on Egypt,

After that he’ll send you from here as he’d send a bride,

He’ll drive you in droves out of here.” . . .

And Moses said, “So says the Lord,

Around midnight I’m going out into Egypt

And every first born in Egypt is dead

From the first born of Pharaoh who’ll sit on his throne

To the first born of the maid behind the millstones

And every beast of burden’s first born

And there will be a great shriek in the land of Egypt

Such as has never been and such as won’t be again

And to all the children of Israel

No dog will wag its tongue, neither man nor beast

So that you know the Lord discriminates between Egypt and Israel

And all these servants of yours will come down to Me

And bow to Me saying, ‘Go, you and the people at your heels’

And after that I’ll go.” And he went from Pharaoh’s presence in a fury.

But the Lord said to Moses, “Pharaoh won’t listen to you—

So as to increase the examples I’ll make of the land of Egypt.”

Pharaoh’s warning to Moses not to look on his face again lest he die is both pathetic and accurate. When Moses does see Pharaoh again, it is at Pharaoh’s request and it’s the middle of the night—when nobody can see anything. By then, Pharaoh’s the one begging Moses to intercede so that he himself won’t die in the general carnage.

And it was midnight and the Lord struck every first born in Egypt

From the first born of Pharaoh who’d sit on his throne

To the first born of the prisoner housed in the pit

And every beast of burden’s first born.

And Pharaoh rose that night

And all his servants and all Egypt did, too

And there was a great shriek in Egypt

For there was no house without a corpse in it.

And he called Moses and Aaron at night, saying:

“Get up and get out from inside my people,

Both you and the children of Israel, and go worship the Lord just as you said,

Your sheep too, your cattle too; take what you said

And go—and bless me, too.”

This is the final humiliation: Pharaoh is reduced to asking Moses to pray for him and, as Moses prophesied, to make a sacrifice in his name to the implacable God who has come over his borders, into his houses, and finally into his mind. When the text specifies that the Lord kills not the child of the maid (as promised previously) but the child of the prisoner in the pit, it is no slip of the pen. The Lord went walking to the place where Joseph started his great ascent in Egypt by foretelling what would happen to Pharaoh’s imprisoned servants.

In this portion of Bo, we revisit first Hagar, then Joseph, before seeing how the cycle of slavery and abuse is finally ended with the Hebrews having undergone a 400-year punishment for abusing Hagar, and with Egypt, in turn, being crushed completely in order to pluck the Israelites back out of it like pips from an orange. The Lord started a cycle with Abraham that he would complete with Moses, only to make the great point, reiterated a total of 36 times in the Torah: do not abuse the stranger, because you were a stranger in Egypt. The subtext is clear: do not do again what you did then, nor ever do what they did to you, because what I did to them I can do to anybody.

More about: Bo, Exodus, Hebrew Bible, Moses, Pharaoh, The Monthly Portion, Torah, Vayikra