Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Mosaic reader Lynn Goucher writes:

I am a Jew by choice, who converted formally a little over a year ago. I was raised in a secular Christian home and have always been perplexed and somewhat disgusted by the Christian obsession with the devil. Although Christians insist that the devil appears in the Torah, my understanding is that the biblical Hebrew word satan, from which comes the name Satan, has been mistranslated as “devil” when it really means “obstacle.” Am I right or wrong?

The answer is: both. It depends partly on which books and periods of the biblical corpus one is looking at; partly on how one reads them; and partly on which post-biblical commentators one chooses to read them with.

The earliest occurrence of the noun satan (pronounced sah-TAHN) in the Hebrew Bible is in the story of the Moabite leader Balak and the sorcerer Balaam in the book of Numbers. There we are told that Balaam, setting out for a meeting with Balak, was intercepted on his way by an angel who, sword drawn, “stood . . . in his path to be a satan to him.” The Hebrew word comes from a verbal root, a variant of the more common verb satam, meaning to hate or be hostile to, and while it could conceivably be translated in this case as “obstacle,” more accurate would be “foe” or “adversary.” (The latter word is used by the King James Version and most other English Bible translations.) Yet there are other places in the early books of the Bible where “obstacle” might indeed be a better choice, as when Solomon declares in the book of Kings that there is no satan in the way of his building the Temple.

In two late books of the Bible, however, where satan appears, preceded by a definite article, as ha-satan, we are on trickier ground, because in this case the reference is clearly to a specific figure. One of these is the book of Zechariah, in which the prophet has a vision of the Temple’s high priest “standing before an angel of God; and the satan was standing to the right of him to oppose him [l’sitno].” The second, better known passage is the introductory scene from the book of Job, where we are told:

Now there came a day when the sons of God [i.e., the angels] came to present themselves before the Lord, and the satan, too, was among them. And the Lord said to the satan, “Where are you coming from?” And the satan answered the Lord and said, “From roaming the earth and going about in it.”

In both places, the King James translates ha-satan not as “the adversary” but as “Satan,” treating it as a proper name. Hence the belief that the devil appears in the Hebrew Bible.

Is this belief justified? It certainly does not represent the only way the text can be read. For one thing, “ha-satan” in Job and Zechariah can be quite plausibly understood not as a name but as a descriptive phrase meaning “the adversary.” Interpreted in such a manner, the satan of Zechariah and the satan of Job might be two different angelic beings, each playing the role of an accuser, a prosecuting attorney in God’s heavenly court.

Moreover, even if they are the same being, this is not the fallen angel and personification of evil of Christian tradition. The satan in Job is a member in good standing of God’s angelic retinue and not necessarily evil at all. He has an unpleasant job to perform and he performs it, but it is one, so it is implied, that has been assigned to him by God, who does not look askance at his undertaking it.

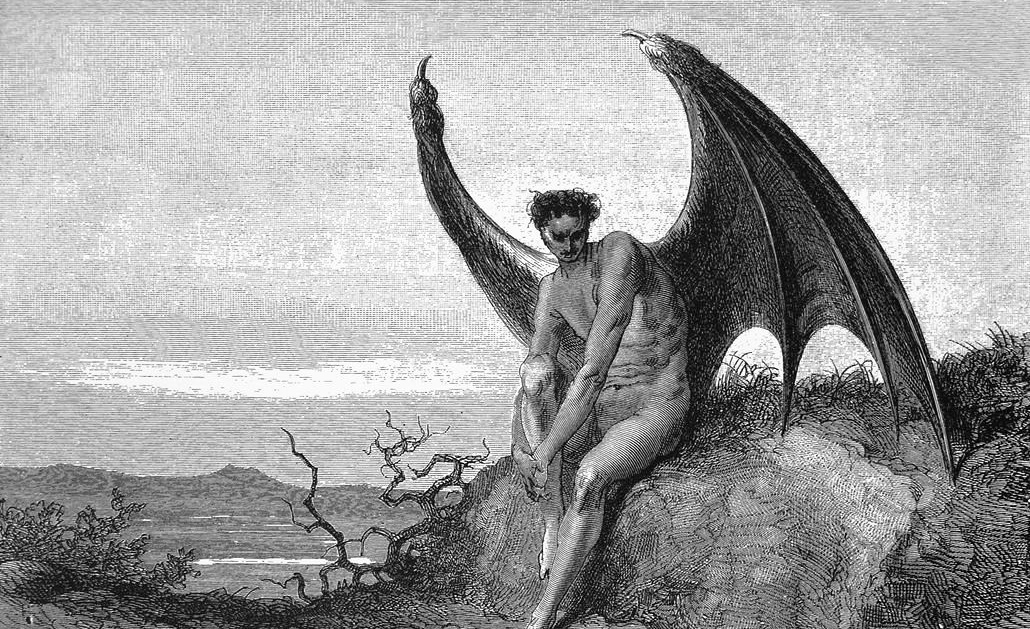

In the New Testament, by contrast (and in part under the influence of Jewish apocryphal literature that was never accepted as normative by the rabbis), the satan became what he was henceforward to be in Christian tradition. He was now the leader of a rebellion of wayward angels against God and the source of the sin that entered the world with the seduction of Adam and Eve in Paradise—“that old serpent,” as the book of Revelation puts it, “called the Devil and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out [of heaven] into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.”

The pan-European word “devil” (German Teufel, French diable, Italian diavolo, etc.) comes from Greek diabolos, “slanderer”—a translation, already found in the Septuagint, of satan in its sense of “adversary” or “accuser.” But whereas the diabolos of the Septuagint, a Jewish translation of the Bible into Greek dating from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, can be construed as simply an adversary, in the New Testament he is clearly the Adversary, the sworn enemy of man and God.

In post-biblical Judaism, it is true, we sometimes find the figure of the devil, often referred to by his angelic name of Samael, similarly conceived of as an independently malicious force of cosmic import. Indeed, in a book like the 8th-century midrashic work Pirkey d’Rabbi Eliezer, we encounter the same idea that is expressed by Revelation. Samael, we read there,

was the greatest prince in heaven, and he took his band and descended [to earth]. . . . The Torah [saw this and] cried out, “Samael, the world is newly created! Is this a time to rebel?” . . . Yet everything the serpent did and said [in the Garden of Eden] was Samael’s work.

But this was hardly a uniform Jewish view in the way that the existence of the devil was a uniform Christian one. In fact, no lesser an authority than the great 9th-century rabbinic scholar and theologian Saadiah Gaon denied such an existence entirely. The satan in the book of Job, he held, was not a supernatural being at all. In the words of the 11th-century Baḥya ibn Paquda:

The Gaon Rabbi Saadiah explained that the satan was an ordinary human being who falsely accused Job out of hatred and jealousy of his success and of the magnitude of his good deeds, and that the “sons of God,” too, were men like him who were Job’s enemies. It was their practice to get together on certain days of the year to worship God [as His sons] and have a great banquet . . . to which also came the most prominent of them, who was called the satan because, being the most envious of Job, he was his greatest accuser.

I imagine Lynn Goucher will find Saadiah more congenial than Pirkey d’Rabbi Eliezer. As a Jew, she’s welcome to choose between them.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Hebrew Bible, Satan, Torah