I have no bones to pick with Martin Kramer’s essay, “The May 1948 Vote that Made Israel.” He probably has it right: in the People’s Administration meeting on May 12, there was in fact no vote on whether or not to declare the establishment of the state of Israel on May 14-15—but there was a vote to omit from the forthcoming Declaration of Independence any mention of the new state’s boundaries.

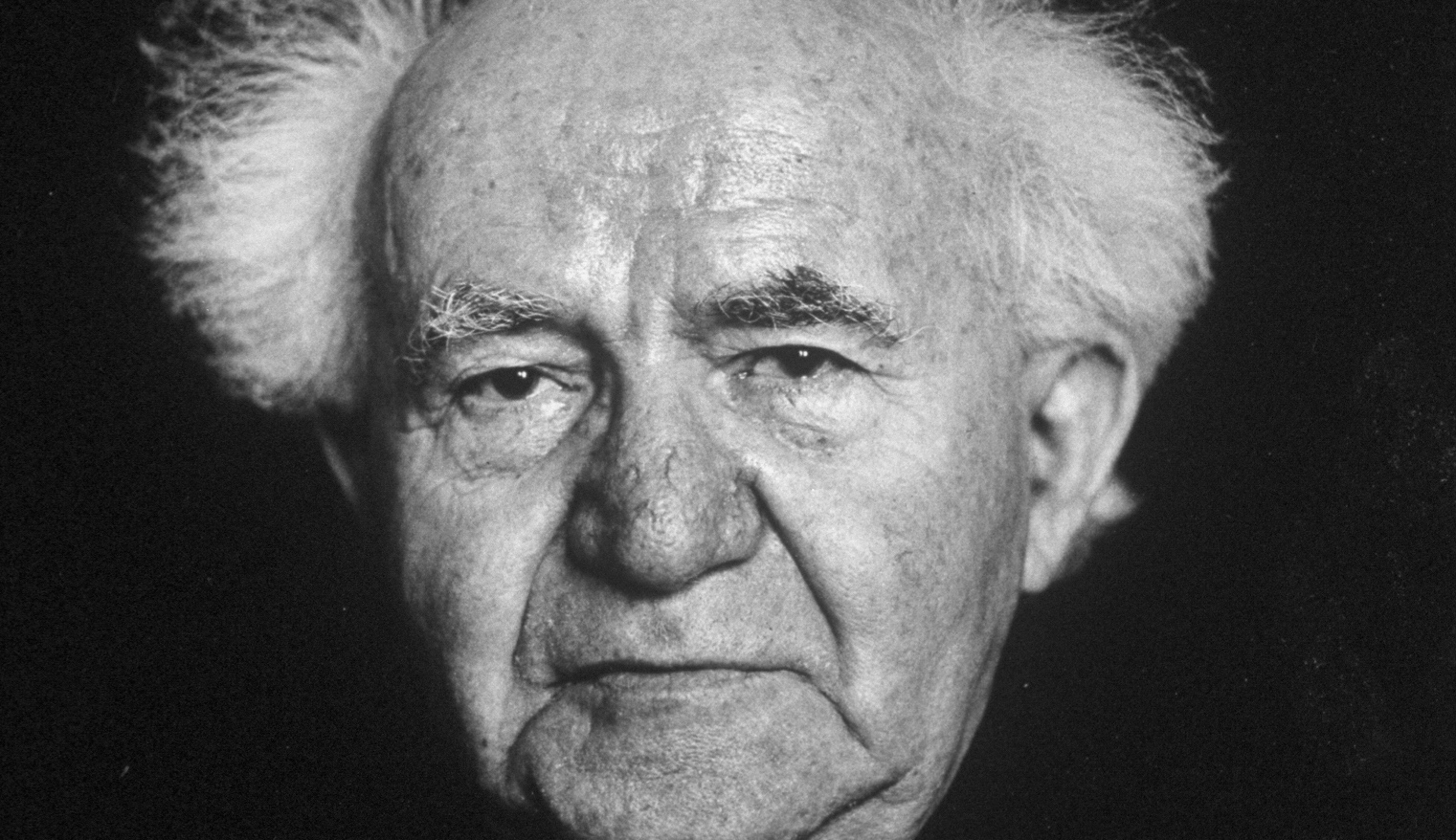

David Ben-Gurion, who chaired the meeting, certainly hoped that by the end of the ongoing war with the Arabs, Israel would emerge with more territory than the UN had apportioned to the Jewish state in its partition resolution of November 1947, and was convinced that not defining the state’s borders prematurely would facilitate such an expansion. In fact, at the cessation of hostilities and the signing of armistice agreements between Israel and its neighbors in 1949, the Jewish state would end up with 78 percent of the land mass of Mandatory Palestine, as opposed to the 55 percent accorded it in the UN resolution.

This expansion was rooted in how the war ended militarily—but also in the nature of Zionism. Zionism was an “expansionist” movement in the sense that its practice was expansionist. From 1882, when the movement arose, until 1948, that practice consisted of planting settlements in the Land of Israel and then planting settlements around the original settlements to give them greater security, and then planting a third ring of settlements for the same purpose, and so on. It was a continually “expanding” enterprise.

And there was also a measure of expansionism in Zionist ideology. Its aim was not, as many Arabs charged at the time, to found a new Jewish kingdom stretching from the Euphrates to the Nile in line with biblical promises. But, from the first, Zionist leaders envisioned the establishment of a Jewish state in all of Palestine, from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. In 1919, when the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann appeared before the World War I victors at the Paris Peace Conference, he presented Jewish territorial demands as encompassing all of what was to be Mandatory Palestine as well as part of southern Lebanon and the east bank of the Jordan eastward to the line of the Damascus-Hijaz railway, as far as the outskirts of Amman, thus including the lands of the Golan, Gilead, Moab, and Edom—areas settled by the Hebrews in biblical times.

Mainstream Zionists dropped these demands only after the Allies in Paris and, subsequently, British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill said “no,” and after Britain in March 1921 awarded all of Transjordan as an emirate to the Hashemite prince Abdullah. (Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionists, for their part, continued for decades to lay claim to Transjordan.) In 1937-38 the mainstream, now in response to the recommendations of the Peel Commission, even acquiesced in establishing, at least for the time being, a Jewish state “the size of a tablecloth” (in Weizmann’s phrase).

By November 1947 and the UN partition resolution, as we’ve seen, the tablecloth had grown somewhat and now encompassed 55 percent of Mandatory Palestine. But the almost instantaneous launch of the armed effort by Palestine’s Arabs, backed by the surrounding Arab states, to prevent the emergence of a Jewish state—they began shooting on November 30, the day after the resolution’s passage—gradually persuaded the Zionist leadership headed by Ben-Gurion that “if they want war, we’ll give them war.”

And here we reconnect to the May 12, 1948 meeting that is the focus of Martin Kramer’s essay. The stance adopted at that meeting by Ben-Gurion and endorsed by the majority—namely, not to define or restrict the future Jewish state’s geographical contours—had already been charted two months earlier in a March 10 operational blueprint, “Tokhnit Dalet (Plan D),” of the Haganah general staff. This document preceded the Haganah’s April switch to an explicitly offensive posture from the heretofore defensive posture of mainly reacting to Arab aggression. But it also laid some of the groundwork for that switch.

Plan D was signed by Yigael Yadin, the Haganah’s and later the IDF’s head of operations and the individual who actually managed Israel’s war through most of 1948. (The chief of staff, Ya’akov Dori, was chronically ill.) The plan instructed the Haganah’s brigades to secure the border areas of the new state as configured in the partition resolution and their internal lines of communication. But, in the preamble, Plan D also charged the brigades with securing “the blocs of settlement and the Jewish population outside these borders [emphasis added].”

Left unsaid was what the “blocs” were—but, like Yadin, the brigade commanders understood them to be three in number: Jewish western Jerusalem and its satellite communities (with about 100,000 Jews), western Galilee with its half-dozen kibbutzim and the coastal Jewish town of Nahariya, and possibly the four kibbutzim of the “Etzion Bloc” between Bethlehem and Hebron.

Western Galilee and the Etzion Bloc were in territory allotted by the partition resolution to the Palestinian Arab state. Jerusalem and its immediate environs had been earmarked for international control. And then there was the road from the Jewish-populated coastal plain to west Jerusalem, which ran through a narrow “corridor” in areas assigned to the Arab state and dominated by Arab villages.

Hence Ben-Gurion’s concern on May 12 not to commit the eventual Jewish state to borders that would exclude from it these three areas and perhaps additional ones. Indeed, during April-June, in the course of the fighting, western Galilee was conquered by the Haganah and “added” to the Jewish state, as were west Jerusalem and the corridor linking it to the coastal plain. As for the Etzion Bloc, located on the West Bank, it fell to Arab attack on May 12-14; its four kibbutzim were leveled, and the entire area was occupied and eventually annexed by Jordan.

Two more bits of subsequent information are needed to fill out and supplement this picture of what was decided on May 12, 1948.

The first is that four months later, on September 26, during a truce in the fighting, Ben-Gurion proposed to his cabinet that the IDF launch an offensive to conquer eastern Jerusalem and the Ramallah area in the northern West Bank and/or the area of Hebron in the southern West Bank. The cabinet voted the proposal down, in a decision that Ben-Gurion would lament in later years.

The second is that in March 1949, after hostilities had ended but before Israel and Jordan signed the armistice agreement consolidating the postwar borders, General Yigal Allon, the head of the IDF’s southern command, proposed that Israel conquer the West Bank in toto. But to this Ben-Gurion himself said “no.” The April 3 armistice agreement duly left the West Bank under Jordanian rule.

In sum: while in 1948-49 Ben-Gurion was highly interested in expanding Israel’s borders beyond the confines of the territory allotted by the UN partition resolution, he also refrained from supporting the conquest of the whole Land of Israel. Perhaps he feared that the great powers would prevent such an outcome; or perhaps he wanted to reach a peace agreement with Jordan (which an Israeli conquest of the West Bank would have rendered impossible); or perhaps he thought it “fair” that part of Palestine remain under Arab sovereignty while the Jews gained and retained the lion’s share.

Whatever the reason, thus it was that the 1948-49 war ended in a partitioned Palestine—until, with Israel’s victory in June 1967, the West Bank (and the Gaza Strip) would come under Israeli rule.

More about: David Ben-Gurion, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism