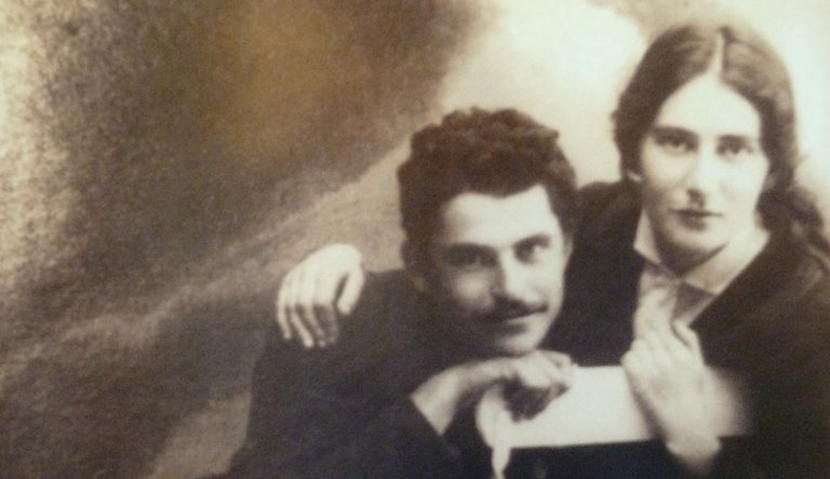

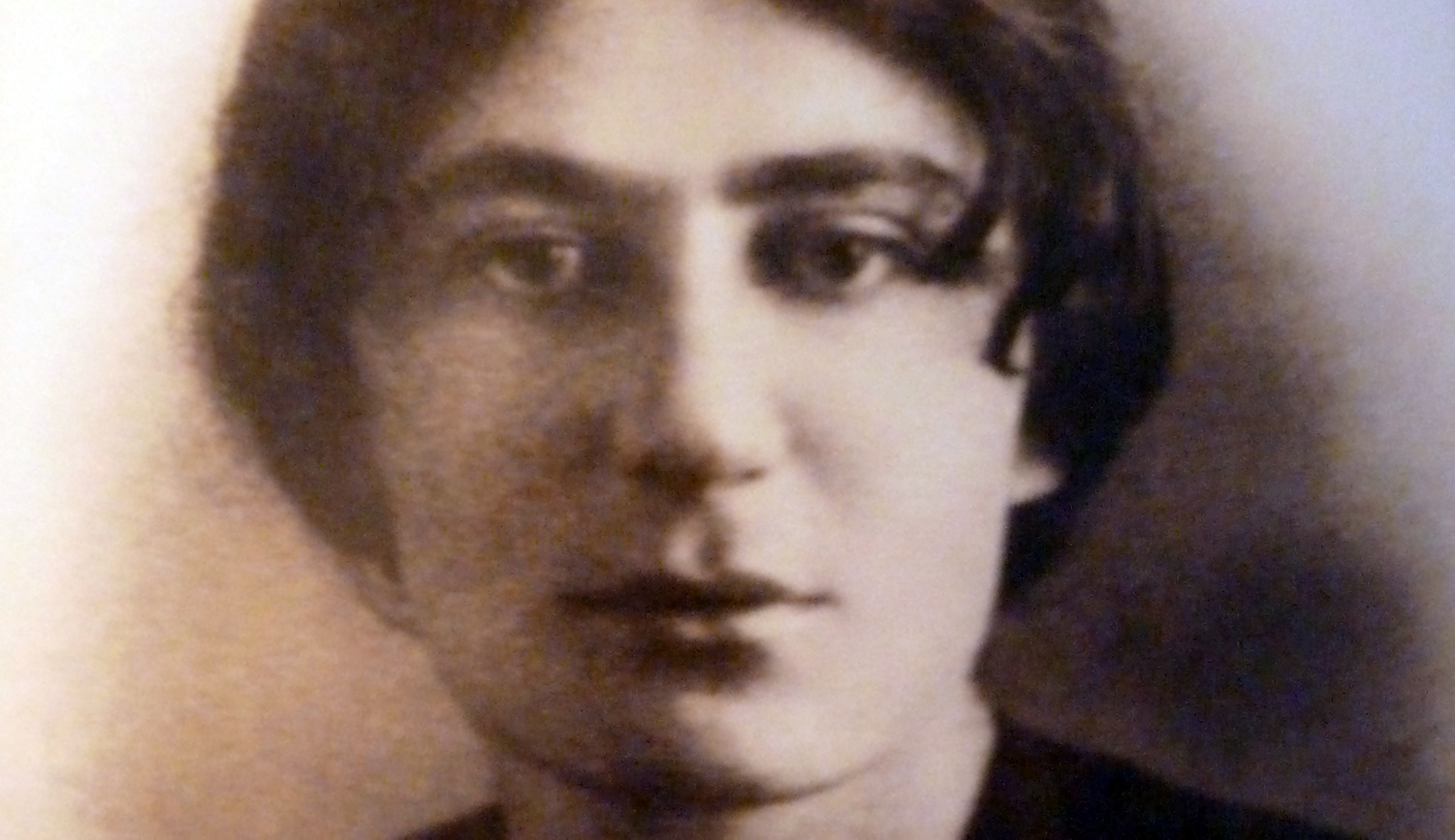

In his essay on the poet Raḥel, Hillel Halkin offers a fascinating study of her too-brief life (1890-1931), her poetics, and the unique place she occupies in the Hebrew literary landscape. Certainly, against the background of the pioneering Zionist ethos of her time—nationalistic, idealistic, and collectivist—the intense individualism of Raḥel’s verse stands out. No less deeply committed to the Zionist enterprise than other poets cited by Halkin, notably Uri Tsvi Grinberg and Avraham Shlonsky, she devoted herself mainly to the exploration of such seemingly inward emotions as sadness, longing, humility, and self-doubt.

The study of poetry on its own terms is a noble literary ideal, but it is difficult to read the poetry of Raḥel without also ruminating upon the personal circumstances, especially the disease to which she would eventually succumb at the age of forty, that may account for the themes of suffering, loneliness, and longing that run through her work. It is perhaps for this reason that Halkin in the end deems her to be, with emphasis on both adjectives, a “great minor poet”: that is, one who deals with localized themes, seemingly without obvious public import, but who nevertheless addresses them with a clarity and virtuosity that ensures he or she will never be forgotten—as, in Israel, Raḥel has indeed never been.

Yet might this major/minor distinction, which Halkin applies with subtlety and generosity, ultimately be something of a false choice?

No one has been more aware of the limitations of Raḥel’s verse than Raḥel herself. “I only know how to tell of myself,/ My world is like the world of an ant,” she wrote. But, as Halkin notes, such statements are also somewhat faux-humble. Raḥel understood very well what nationalist poetry should look like, and even drew on its motifs when she saw fit. Overall, however, she deliberately chose a different approach, and did so in the service not only of a poetic “path of simplicity”—the aesthetic style she aspired to—but also of a specific and sophisticated set of ideas, symbols, and themes.

Take, for example, the poem “To My Land,” translated beautifully by Halkin:

I have not sung to you, my land,

Psalms of high praise,

Or glorified you

With a hero’s deeds;

Only with a tree

Planted by the Jordan’s banks,

Only with a path

Trod through your fields.How little, Mother,

That has been, I know,

How small

Your daughter’s gift:

Just a cry of joy

When dawn broke over you,

Just, for your poverty,

A tear of grief.

Here, acknowledging (in, no doubt, one of her faux-humble confessions of inadequacy) that she neither writes epic poetry nor fights heroic battles, the speaker insists that her two hands have nevertheless done something, they have planted and nourished. More, she has augmented the agricultural feats of her fellow ḥalutsim by her very presence, her personal “path trod through your fields.” In a more literal translation, this last phrase would read “only a path have my feet conquered,” implicitly placing into consideration the manner in which individuals not only conquer but also cultivate the land.

In the poem’s second stanza, the speaker describes the nature of her individual contribution. However “little” or “small” her offerings may be, they are also uniquely feminine: the offerings of a daughter to her mother. If the Land of Israel is indeed a mother, such gifts from a beloved daughter are all the more appropriate. In fact, the word Raḥel uses for “gift” here is “minḥah,” a direct allusion to the grain offering that in ancient times would be brought to the Temple in place of or alongside more expensive and elaborate animal sacrifices. Modest by Temple standards, it was nevertheless a critical component of the sacrificial landscape, and one that carried the same biblical imprimatur of divine approval.

From this springs the boldness of the speaker’s final lines, weaving the poem’s themes together. As the day lights up, the speaker’s “small” song bursts forth in a youthful “cry of joy” over the Jewish homeland—a cry of joy no sooner voiced than supplemented by its necessary counterpoint, a maternal “tear of grief” over the land’s forbidding “poverty.”

In sum, Raḥel has enlarged what in other hands might be an abstract and sentimental nationalist cliché to embrace an emotion more nuanced, more precise, more linked to Jewish literary tradition, and more profound. Halkin well captures the overall effect of this finely wrought work: “There are no false steps in ‘To My Land.’ Its simplicity presupposes daring just as its humility presupposes pride.”

Raḥel’s biblicism, glinting selectively through the lines of “To My Land,” is altogether a salient aspect of her verse and one that Halkin rightly highlights. The depiction of biblical characters in verse is an ancient Hebrew form, beginning with the Bible itself. To Halkin, Raḥel’s place in this longstanding tradition is both new and unique. As he puts it:

[F]or a sense of closeness to a biblical character so great that it erases all distance and transforms her or him from a literary or historical subject to an immediately felt human presence, Hebrew literature had to wait for Raḥel.

Raḥel doesn’t just write about biblical figures, and more often biblical heroines; she conflates her perspective with theirs to the point where she and they are one—while all along maintaining fidelity to the content and tone of the original biblical account.

When John Milton wrote Paradise Lost, an epic narrative for English Christians that would hold its own against Roman and Greek epics, he chose the Bible as his source. In doing so, Milton necessarily forged an anti-epic worldview, one that challenged and even undermined classical and heroic values. Raḥel’s reimagining of the Bible takes this move a step further. Thus, in the poem Mineged (“From Across” or “As Against”), the speaker articulates her personal disappointment at her own thwarted love and hopes by simultaneously evoking a key biblical moment pregnant with both literary and national significance.

In the poem, Moses is atop the mountain of Nevo, gazing “from across” at the Land of Israel that he will never be allowed to enter (the translation here is by Robert Friend):

The ear listens.

And the heart.

Has He come? Will He come?

In every waiting for,

a never,

the sadness of Nevo.

For the poet, ever since the Bible, “the sadness of Nevo” signals both a personal and a national predicament. The Torah itself is defined by its lack of a “happy ending” for Moses and the Israelites, and in this poem the speaker—the person, the Jew, and the Zionist waiting for someone or something to come—is defined by that same lack.

What Raḥel accomplishes here and in her other biblical poems is twofold: without a hint of grandiosity or sentimentality, she both elevates her personal longing to something of biblical proportions and, through the frank immediacy of her verse, brings an ancient moment to life. And she does this seemingly effortlessly, as in another, particularly poignant poem, “Barren Woman” (again in the translation of Robert Friend):

If only I had a child,

curly-haired and dark

to take by his small hand

as we slowly walked through the park.

A child.Uri I’d call him,

a name clear and mild,

a fragment of light.

“Uri!”

I’d call him,

my small, dark child.Still, like Rachel

the Mother, I mourn,

like Hannah pray

For the unborn,

and wait, still wait

for my child.

It’s not easy to unpack the simultaneously interacting layers in this poem. In “wait, still wait for my child” there is a hint of the formula used by Jews in relationship to the messiah: “and even if he tarries, every day I wait for him.” The emphasis on naming has equally deep biblical resonance, and the specific name chosen—Uri, from “light,” a simple, still-popular Hebrew name—recalls the language through which God first calls the world into being and thereby creates all of life. Finally, the speaker’s own outwardly modest wish assumes world-historical significance just as, in its own modest but insistent manner, the biblical matriarchs’ unquenchable longing for children ultimately transformed the course of Jewish and world history.

With a few choice words, Raḥel illuminates the unbroken thread (another frequent image in her verse) that connects the biblical past with her own working, giving, suffering, yearning existence and, yes—as Halkin marvelously demonstrates in his exegesis of her one openly Zionist poem—with her exultant and wildly ambitious immersion in the project of reclaiming the Land of Israel. The powerful if outwardly demure immediacy of Raḥel’s poetry is itself an expression of Zionism’s this-worldly orientation, linking the modern Jewish nation back to its roots in the consuming actuality of the land and in the foundational text of the Bible that was born there.

And all of this is why I ask, at the risk of oversimplifying Hillel Halkin’s concluding assignment of Raḥel to the status of a “great minor” Hebrew poet: what would a great major Hebrew poet look like, if not like this?

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism