The scandal of the Jewish Museum in New York, as Menachem Wecker’s fine essay shows, is a scandal caused by immense curatorial ignorance, both cultural and religious, combined with the arrogant belief that such ignorance doesn’t really matter. In his response to Wecker’s essay, Tom Freudenheim expands this indictment, noting that a palpable hostility toward Jewish religion and traditions seeps into the museum’s presentations.

Last year, in reviewing the museum’s new permanent exhibition for the Wall Street Journal—the same exhibition, Scenes from the Collection, that Wecker takes to task in Mosaic—I suggested that this venerable institution was not only abrogating its mission as a guardian of Jewish identity but also on its way to becoming one of the most offensively banal Jewish museums in the world. But as the awkward introductory panel to the Scenes exhibition makes plain, today’s museum isn’t really interested in anything like a “Jewish identity.” Instead, it speaks of plural, fluid, and indeterminate Jewish identities, and then has the temerity to propose that the museum itself might serve as a “guide for the formation of new” such identities.

In this respect, the museum seems to be promoting itself as a 21st-century reboot of such Jewish institutional innovations as the early synagogue, or perhaps as a more diverting version of the Babylonian Talmud, with lots of pictures. But, to say the least, there’s a difference: where those ancient initiatives shaped exilic Judaism with learned debate, imaginative interpretation, and profound reverence, our new museological “guide” makes no demands whatsoever on anyone. Assuming no education, offering little knowledge, and affecting not to care about either, it promises only that its handsome installations will inspire new forms of an “ever-changing” Jewish identity.

I haven’t had the heart to revisit these “scenes” since reviewing them, but Wecker’s descriptions convince me that although the particular artifacts on display may have rotated or changed, the effect is the same. In keeping with the organizers’ vision of Judaism as indefinite and endlessly malleable, they have striven for something similar by avoiding the kind of “master narrative” that has traditionally shaped museum exhibitions.

In fact, however, just such a master narrative is very much at work. It is a narrative of dismantlement, and it is particularly evident in the main gallery, “Constellations.” Here, we learn from a wall plaque, “some of the most powerful works in the Jewish Museum’s collection” have been gathered together with the aim of expressing “aspects of Jewish culture, history, or values, while they also reflect universal issues of art and its relationship to society.” Exactly what those aspects are, or how they reflect on “universal issues,” is unclear. Instead, we’re assured that the mere juxtaposition of these “widely varied artworks” will reveal “multiple meanings” as they engage in “conversations” with each other. Some of these interactions, we are assured, will even illuminate that “ever-changing nature” of Jewish identity with which the museum is so preoccupied.

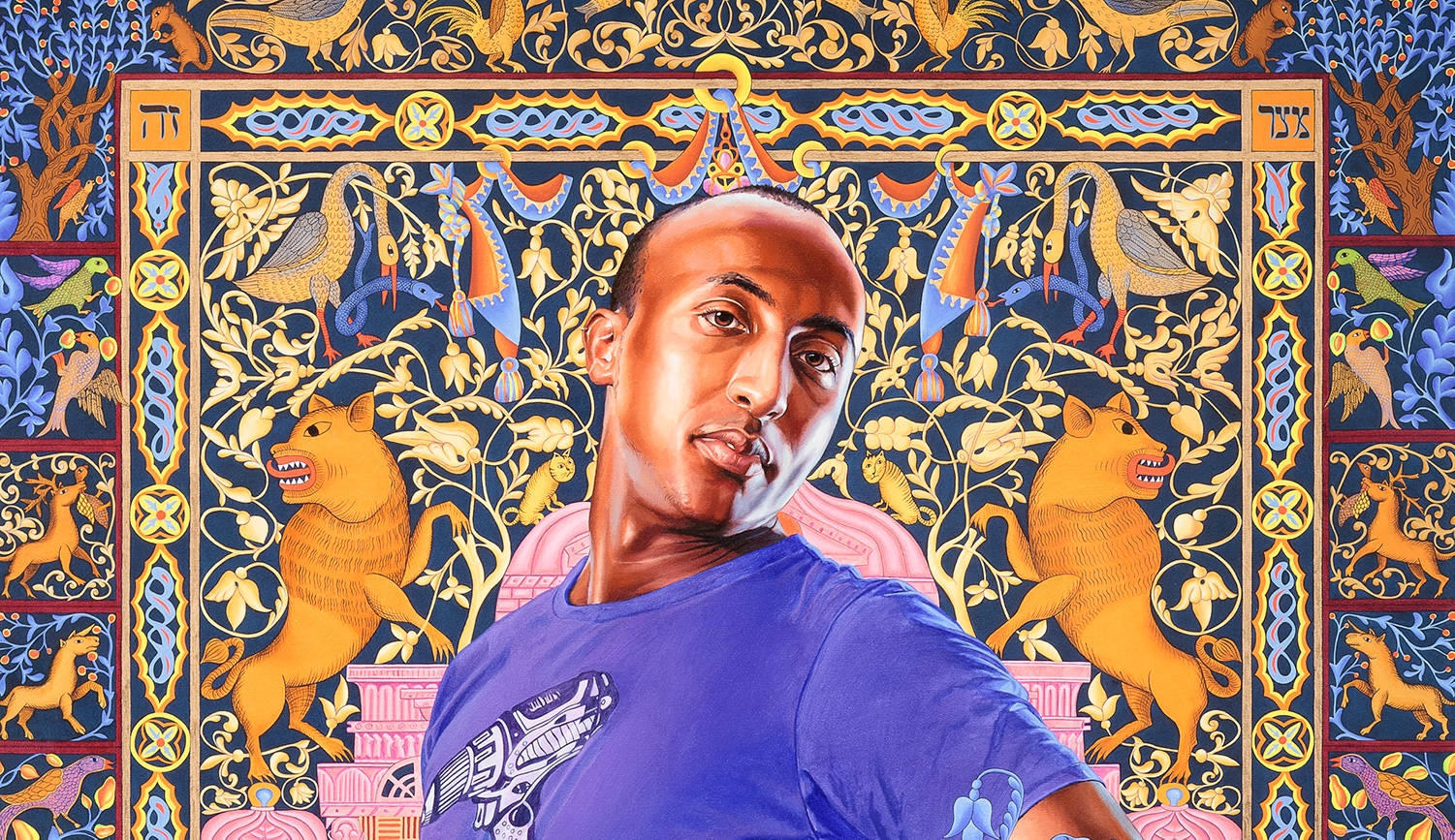

Evidently gone from “Constellations” since the time of the exhibition’s opening was one such “conversation”: the coupling of a papier-mâché golem constructed by the avant-garde theatrical director Robert Wilson out of Japanese and Chinese newspapers with a late-19th-century crimson velvet dress made for a Jewish bride in Marrakech. Still present, however, to judge by Wecker’s essay, is another union: a gaudy portrait by Kehinde Wiley next to an imposing wooden ark of the Torah from a turn-of-the-20th-century American synagogue; presumably, the “conversations” inspired by this particular schismatic union have remained on view because they have proved of greater value.

Yet what is the net effect of such interactions? It can only be to ensure that the weightier, more evocative, and more important historical or religious artifact—the velvet dress from Marrakesh, the wooden ark from Iowa—is made to seem artificial and inconsequential by being mounted, without context, alongside an artifact that is already ironic and inconsequential.

The same process of dismantling continues in other galleries. When I saw it, the “Taxonomies” installation held all manner of Jewish ritual objects, from Sabbath candlesticks to circumcision knives, presented as curiosities: not only stripped of function and meaning but lacking any discernible reason for their existence, almost as if they were relics from an antique civilization that once observed some primitive customs that we can now appreciate for their aesthetic piquancy—or would appreciate, if, beyond the minimal information offered on interactive display screens, we had any clear idea of what those customs were or why they were kept and transmitted.

Behind this master narrative of dismantlement, as Tom Freudenheim suggests, there also lurks a latent hostility to Jewish religious belief; but not to religious belief alone. On my visit, one gallery attempted to give a history of the Jewish star—“a universal motif” (emphasis added), as the museum fetishistically insisted, lest a visitor unthinkingly imbue it with specifically Jewish meaning. What are we to make, then, of the commentary on a photograph of a Tel Aviv beach with an Israeli flag flying from a lifeguard tower? The highly particularistic star on that highly particularistic flag, we’re helpfully instructed, ends up “subverting” our pleasure in the surrounding universal serenity.

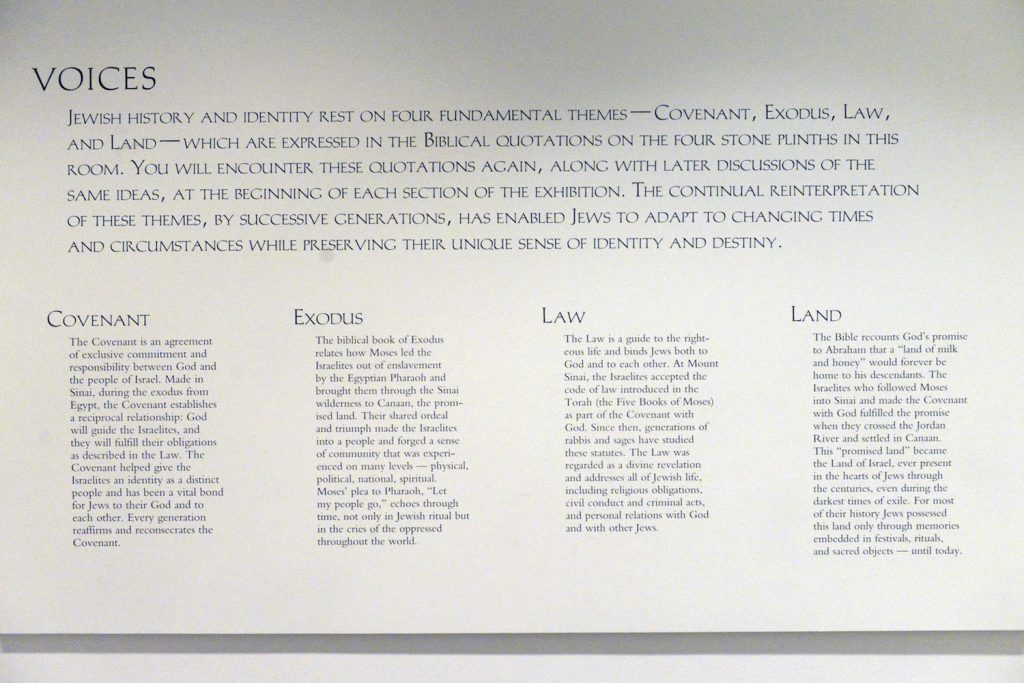

As a stark counterexample to the destructive inanities of Scenes from the Collection, Menachem Wecker admiringly adduces the museum’s previous, now-supplanted permanent exhibition, Culture and Continuity: The Jewish Journey. The governing assertion of the earlier exhibition was that “Jewish history and identity rest on four fundamental themes”—themes that had informed Jewish thought and belief for two millennia: Covenant, Exodus, Law, and Land.

What a distance this marks from the current exhibition, where nothing so simple, so confident, so solidly based in historical and religious consciousness—or, for today’s curators, so hopelessly provincial—is even mentioned. And yet, if those curators were indeed serious about encouraging “conversations,” they might have pondered the example of their predecessors, whose slightly textbookish but insightful survey of Jewish history and belief posed all sorts of conversation-starters. How has Judaism survived? What connection was there between the ancient Israelite kingdoms and the evolution of Jewish belief and practice? How did differences in worship and culture lead to differences in the artifacts and ritual objects produced by Jews? What is the meaning of Judaism’s festivals and sacred days? How did Judaism help shape modernity while being transformed by it? No exhibition in the United States now attempts anything even close to this.

A conversation between Scenes from the Collection and Culture and Continuity might raise other questions as well. Is Jewish identity really “ever-changing”? And more urgently: what social, cultural, or other influences might have led to the creation of an exhibition that seems deliberately to flout any real connection to the Jewish past or to Judaism? How to characterize a Jewish museum in which everything in its collection intimately connected to Jewish history and religion is treated as an excuse for a “conversation” deflecting attention away from those origins, or else presented as a superannuated curiosity? Why is such a museum so intent on dissolving Jewish identity altogether into a catholic embrace of “universal values that are shared among people of all faiths and backgrounds,” the museum’s repeatedly emphasized touchstone? Imagine such a self-diminishing approach by any other identity museum built to celebrate a people and its history!

Now that the Jewish Museum has aggressively abdicated the role for which it was founded, discarded its own origins as irrelevant, and demolished one of the few institutional accounts in the United States of the history of the Jewish people and the Jewish religion, one can hardly imagine it playing any role at all in educating the public or, indeed, Jews themselves about the nature of Judaism and of specifically Jewish values, or illuminating the complexities of the Jewish historical experience—this, at a time when such an education might, at the very least, help fortify many against the new anti-Jewish sentiment erupting on the current cultural and political scene.

Nor can one imagine such a museum shedding light on why it itself should even exist. Perhaps its great religious and historical collections, so meticulously acquired over more than a century, should be ceded to a real Jewish museum, along with the Warburg mansion that was donated for the purpose of housing them. It’s worth a conversation.

More about: Arts & Culture, Jewish museums