Once, if asked to respond to Ruth Wisse’s fine and penetrating essay on Saul Bellow’s Jewishness, I would have made a point of re-reading each of the novels discussed by her. Having become stingier with my time, however, I decided to make do with re-reading just Ravelstein—and, even then, three surprises awaited me.

The first surprise was that, opening the 2001 paperback edition of Ravelstein that I took from its shelf, I found the inscription: “For Hillel and Marcia with best wishes, Saul Bellow.” Although I remembered the occasion (the only one) on which my wife and I met Bellow, which was at a dinner at Ruth Wisse’s home in Cambridge a year or two before his death, I had forgotten being given the book.

The second surprise, tucked as a bookmark into the novel’s first pages, was a card from a glatt-kosher catering company in New York informing me that the meal served on my El Al flight back to Israel had been prepared under the strictest rabbinical supervision. Glatt kosher? Me? I can’t imagine what I might have done to deserve it.

But the biggest surprise was the last one. Soon after beginning my re-reading of Ravelstein, I realized I had never read it in the first place. Beyond the page of the bookmark, not a single detail was familiar. I had, so it seems, started the novel on the airplane, fallen asleep, and dreamed that I’d read the whole thing.

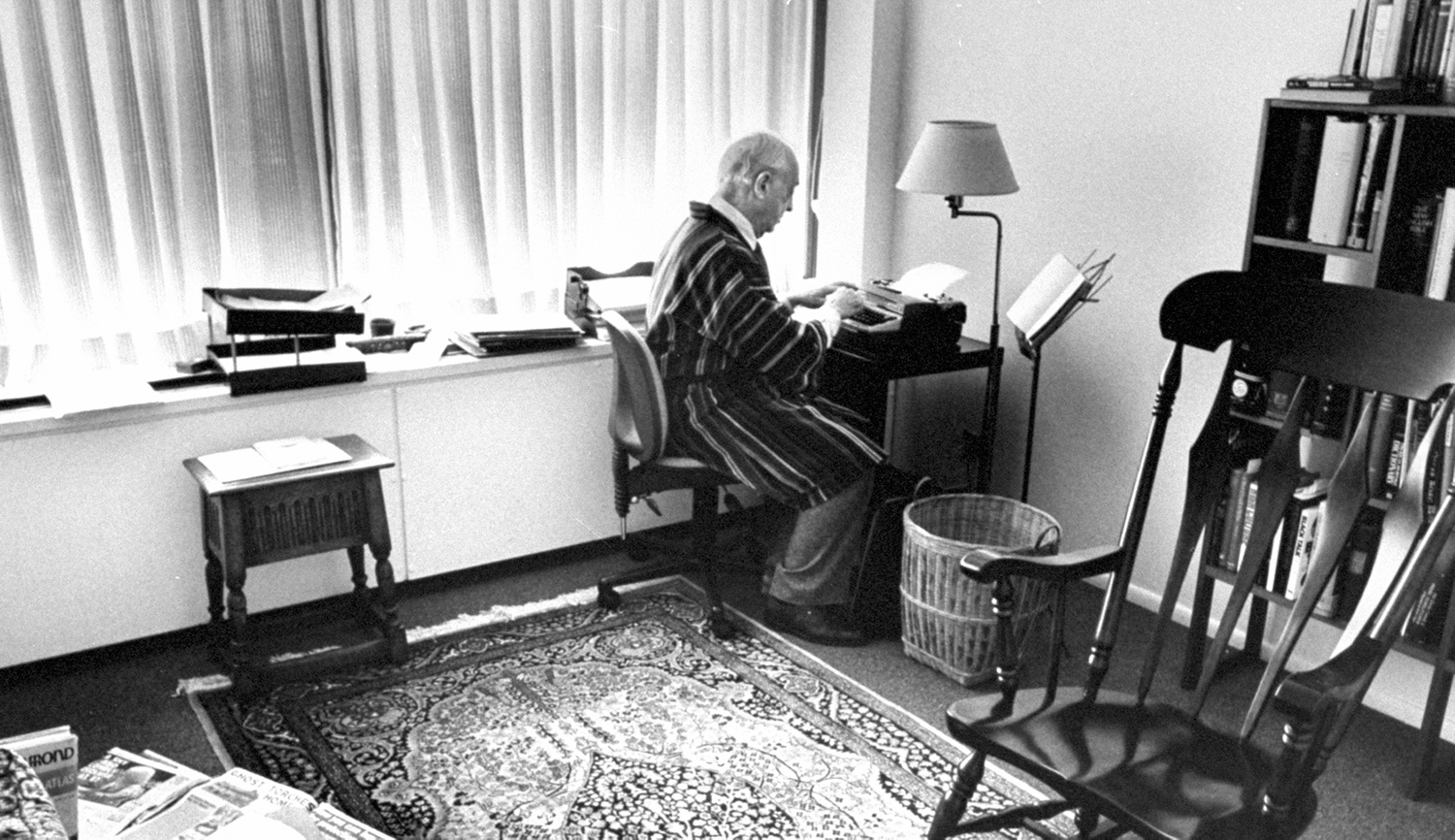

And so I was now reading Ravelstein for the first time—and realizing, well before reaching the end of it, that it was not going to be one of my favorite Bellow novels. The problem wasn’t Bellow. His prose was as sharp and smart as always, if lacking the virtuoso passages of many of his earlier books. (This, I’ve noticed, is a common trait in great writers as they age. They lose all interest in showing off.) The problem was Ravelstein. I didn’t care for the man. And if you don’t care for, or at least care about, a novel’s main character, you can care only so much for the novel itself.

Ravelstein is an odd type: one of a kind. A stern moralist yet also a voluptuary, he is a man with a passionate commitment to the life of the mind and the Socratic pursuit of philosophy who also loves elegant custom-made suits, swanky Parisian restaurants, celebrity-class hotel suites, and exorbitantly priced sports cars.

Moreover, he can now afford all of these things, because he has become, late in life, a celebrity himself: a Jewish University of Chicago professor who has written a book about the intellectual degeneracy of late-20th-century America that, contrary to all expectations, has turned out to be an international best-seller and earned him a fortune. Once forced to scrounge and borrow to pay for his expensive tastes, he can now indulge them as much as he pleases.

And yet not for very long, because he is dying of AIDS. It is his impending death that has made him ask his friend Chick, a well-known novelist and the book’s narrator, to immortalize him in a literary portrait. Ravelstein is gay, and while he has a steady partner at the time the novel takes place, he owes his fatal illness, it would seem, to more casual liaisons.

And this, too, raises a question, because the one idea in the history of philosophy that most grips him is that of the morally elevating nature of Eros, as famously set forth by Socrates in Plato’s Symposium. Human beings, Socrates fancifully relates there, once had two sets of sexual organs, usually male and female but sometimes both male. Punished by the gods, they were split in half, and ever since, as Chick says, “generation after generation we seek the missing half, longing to be whole.” Ravelstein, Chick adds, “rated longing very highly.”

Of course, the question may not be worth raising. The Symposium is among other things a paean to homosexual love, and if Ravelstein, like many gay men, has had a great deal of casual sex in his life, who is to say that he wasn’t diligently seeking his missing half? Why hold it against him?

But something in me did. It was the part of me that did not believe that the life of the mind and an infatuation with BMW 740s are compatible, and that regarded Ravelstein’s Lalique crystal, Pratesi sheets, and George Jensen silver teapots, let alone his one-night stands, as so much goyishe nakhes. (This Yiddish expression meaning “Gentile pleasures” might better be translated as “dumb Gentile pleasures.”) And what an intellectual snob Ravelstein is, too! You couldn’t even get into his courses unless you could read Plato in Greek. “If he had to choose between Athens and Jerusalem,” Chick writes, “he chose Athens, while full of respect for Jerusalem.” I thanked him for his respect, but as a son of Jerusalem I found him somewhat distasteful.

And yet by what right? Who, I was asking myself by the time I arrived at the novel’s final pages, was the real snob: Ravelstein, now dead, with his love of fine things, or me with my superior disdain for them? Was it not as snobbish to judge a man harshly for wearing Turnbull & Asser shirts with gold cufflinks as it was for dressing in stained t-shirts? What a provincial, puritanical son of Jerusalem I was!

Jerusalem versus Athens, Hebraism versus Hellenism: it’s the biggest historical cliché there is, and we can’t get away from it because it’s true. “While Hebraism,” wrote the Victorian poet Matthew Arnold in his 1869 book of essays Culture and Anarchy,

seizes upon certain plain, capital intimations of the universal order, and rivets itself, one may say, with unequaled grandeur of earnestness and intensity on the study and observance of them, the bent of Hellenism is to follow, with flexible activity, the whole play of the universal order.

He couldn’t have said it better.

To seize upon certain plain, capital intimations of the universal order while following the whole play of the universal order: of all the American novelists of the 20th century, Saul Bellow was most engaged in doing this. His whole career as a writer was devoted to it. Sometimes he veered toward one pole (the intimations), sometimes toward the other (the whole play), but he never lost sight of both. “Eternity is in love with the productions of time,” wrote William Blake, and the productions of time—which include Turnbull & Asher shirts and Poulsen Skone tan Wellington boots—fascinated Bellow no less than they enticed his character Ravelstein.

In the end, the dying Ravelstein himself veers back toward eternity. “I could see,” Ruth Wisse quotes Chick as saying, “that he was following a trail of Jewish ideas or essences. . . . He was full of Scripture now. He talked about religion and the difficult project of being a man in the fullest sense.” Well, of course, you might say: a typical case of deathbed repentance. It happened to Heinrich Heine in 19th-century Germany, too. But both Heine and Ravelstein struggled with Hebraism and Hellenism not just at the end of their lives but for all of their lives.

Nor is this Chick’s final memory of Ravelstein. That memory is of him listening joyously to opera on his hi-fi equipment while donning a $5,000 suit, “an Italian wool mixed with silk,” before stepping out into the Chicago winter:

He loses himself in sublime music, a music in which ideas are dissolved, reflecting these ideas in the form of feeling. He carries them down into the street with him. There’s an early snow on the tall shrubs, the same shrubs [described by Chick in an earlier passage] filled with a huge flock of parrots—the ones that escaped from cages and now build their long nest sacks in the back alleys. They are feeding on the red berries. Ravelstein looks at me, laughing with pleasure and astonishment, gesturing because he can’t be heard in all this bird-noise.

For “all this bird-noise” read: the whole play of the universal order.

Hellenism and Hebraism. Veer and veer again. We are lost without both. How hard it is, though, to get the balance right.

I should have talked to Bellow about this at that dinner at Ruth Wisse’s. But his mind was no longer at its sharpest and he spoke little that night, as if not wanting to give himself away. He said what he could with a signed copy of Ravelstein, which it took me a long time to read.

More about: American Jewish literature, Arts & Culture, Saul Bellow