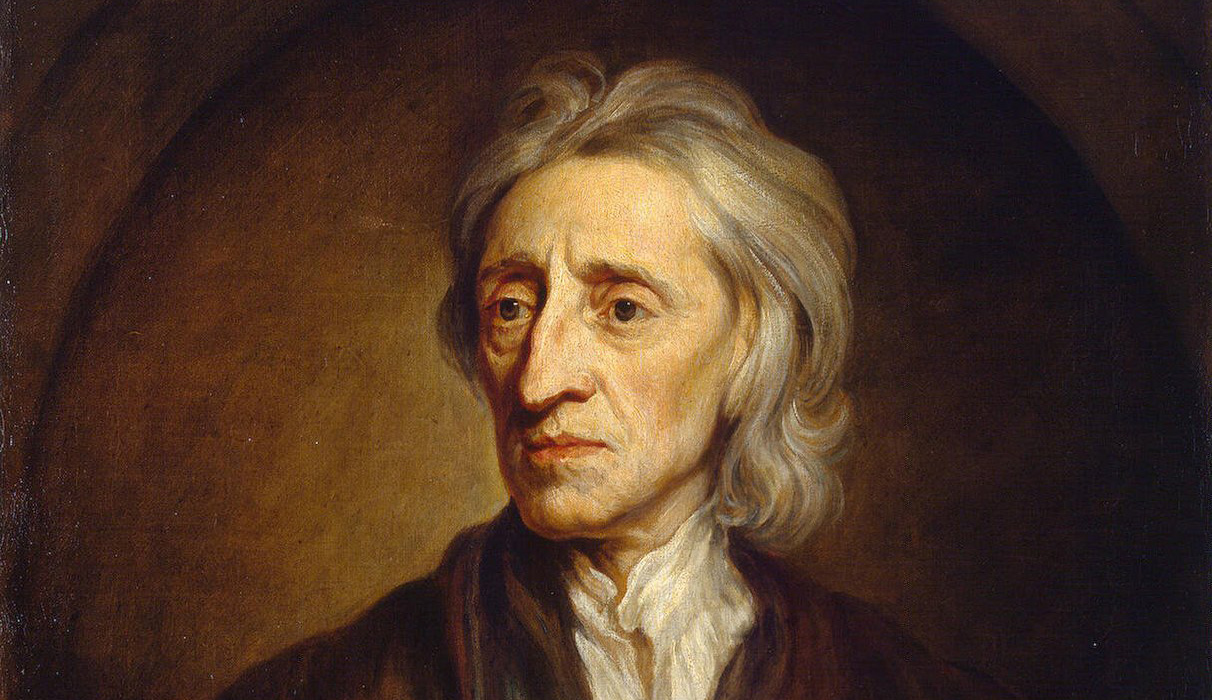

John Locke.

Despite the manifold threats confronting freedom today, the two major-party nominees in this year’s U.S. presidential campaign have devoted astonishingly few words to its defense. This is alarming not least because the protection of individual freedom is the American Constitution’s chief goal.

True, both candidates have put forward a number of policy proposals that in one way or another implicate freedom. Over the long run, however, even freedom-friendly policies will not be enough. We need candidates who cherish the American inheritance of freedom, understand the ideas and interests that menace it, can present in clear and vigorous terms the measures necessary to preserve it, and, if elected, would be capable of shepherding through the legislative process bills that translate freedom’s promise into practice.

It is thus a surpassing virtue of Yoram Hazony’s “Nationalism and the Future of Western Freedom” that it identifies deep connections between discontents sweeping across the world’s leading liberal democracies and the principles of freedom on which the American constitutional order rests. His thesis—that the future of freedom is dependent at once on a recovery of the biblical understanding of the nation and on a repudiation of “the modern world’s most famous liberal manifesto, John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government”—is bold and illuminating.

It is also paradoxical. Many religious men and women may find Hazony’s enthusiasm for the Bible and his strictures against Locke refreshing even as they may be surprised to learn that they themselves represent the hope for freedom in our time; an equal number of secularists would contend that he has things exactly backward. For both parties, there is much to gain from studying the contours of Hazony’s formidable argument—and to consider which aspects of it may be in need of qualification, refinement, or reassessment.

In Britain’s stunning decision to exit the European Union, as in Donald Trump’s call for the restoration of American greatness, there is, writes Hazony, much more to be seen than simple nationalist reaction against the dislocating forces of globalization. The debate over whether liberal democracies will preserve their national sovereignty or become altogether subject to transnational authorities represents nothing less than “a struggle between two antithetical visions of world order.”

One vision, rooted in the Bible and embraced by the ancient kingdom of Israel, is “an order of free and independent nations, each pursuing the political good in accordance with its own traditions and understanding.” The other is the idea of universal empire: “an order of peoples united under a single regime of law, promulgated and maintained by a single supra-national authority.”

The latter vision, Hazony reminds us, dominated the ancient and medieval worlds. In the 16th and 17th centuries, however, the Protestant Reformation redirected Western attention to the biblical idea of free and independent nations. The “Protestant construction,” as he calls it, taught that nations—constituted by distinctive languages, customs, traditions, and religious faiths—have the right to govern themselves, and that legitimate government must protect the people by honoring, at a minimum, “the biblical Ten Commandments given at Sinai.”

For roughly 300 years, Hazony argues, the West grew and prospered under the auspices of this Protestant construction. But since the end of World War II, the idea of free and independent nations has come under increasingly aggressive criticism from Western intellectuals. Their ideal is instead “the liberal construction”: a vision of politics that apotheosizes personal choice and demotes—when it does not altogether obliterate the significance of—family, tradition, and faith. To Hazony, a “classical and still highly influential source” of this liberal construction is John Locke’s 17th-century masterpiece. Captive to the Lockean spirit, liberal elites today reject the national state as an oppressive mix of provincialism, bigotry, and authoritarianism.

Ironically, Hazony notes, the logic of their enmity to the national state has turned Locke’s heirs from friends of freedom into freedom’s foes: enablers of a sweeping new authoritarianism. Promulgating laws to emancipate individuals from the straitjacket of inherited belief and practices, they seek instead to bring all humanity under the sway of transnational institutions serving the utopian goal of planet-wide peace and prosperity. To implement the era of the autonomous individual, they gladly abandon the supposedly now-obsolete devotion to liberty of thought and discussion: they stifle speech, delegitimate dissent, and impose uniformity of opinion and conduct.

This extraordinary ambition to achieve global governance in the name of freedom—an ambition embodied in the European Union and much progressive thought in America—is, Hazony warns, the leading expression in the West of the ancient aspiration to empire. To counter the monumental threat it poses to freedom, he places his hopes in a contemporary revival of the biblical idea of free and independent nations. In particular, he calls for a conservative-led movement made up of “Old-Testament-conscious Protestants, nationalist Catholics, and Jews” for whom the burning question is “how the Western nations can reconnect with the sources of their original, astonishing strength.”

Hazony’s summons to recover the sources of freedom within Western civilization, and particularly its biblical roots, is salutary. He makes a bracing case for nations and the modern nation state, built around a particular people’s familial ties, culture, and religious beliefs and in opposition to dreams of global governance that regard such attachments as so many prejudices to be overcome. His critique of liberal imperialism identifies a powerful contemporary threat to freedom.

At the same time, however, Hazony overestimates the resources within the Bible for understanding the political requirements of freedom and underestimates the resources within modern thought for grasping the ideas, sentiments, moral habits, and institutions that foster freedom.

First, the biblical idea of free and independent nations offers too little when it comes to the freedom of the individuals living in those nations. Freedom among states is no guarantor of freedom within states. Despots can honor borders.

Similarly, teaching that free and independent nations must respect “the moral minimum” of the Ten Commandments won’t secure political freedom and may conflict with its requirements. The Ten Commandments are addressed to individuals: governments do not have parents to honor and neighbors whose wives they should not covet. The Ten Commandments tell us nothing directly, and little indirectly, about the proper limits of government power and the effective means for restraining it—questions central to the modern tradition of freedom. Indeed, a government authorized to enforce the Ten Commandments and so judge what counts as honoring and determine where admiring passes into coveting would possess tyrannical power.

It is to the tradition of freedom, in which John Locke plays a seminal role, that we must turn to understand the political institutions—starting with the separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism—through which free peoples in large, religiously diverse, commercial societies secure the freedoms of religion, speech, press, and assembly; the right of private property; and the guarantee of due process under law.

Second, Hazony misconceives Locke. He writes that “Locke abstracts away the intellectual or cultural inheritance that one receives from being raised in a particular family, community, nation, and religious tradition.” But Locke undertakes this “abstraction” for a specific purpose: to identify the origins, extent, and aim of political power, which in the 17th century required a new foundation because of the devastating criticisms that Locke, among others, leveled at divine-right monarchy.

In justifying the exercise of political power—that is, the right of making and enforcing laws to protect life, liberty, and property—Locke does not deny the importance of family, community, nation, and faith. On the contrary, in Chapter 6 of the Second Treatise, which explains that parental power is grounded in the duty of parents to educate their offspring, he insists on the unique bond generated by parents’ natural ties of tenderness and affection toward their children and by children’s lengthy dependence on their parents. He composed an entire book, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, explaining how parents can effectively discharge their obligation to prepare their children—including their daughters—to become self-governing adults.

In addition, Locke insists that the legitimacy of political power rests on the consent of a discrete group of individuals who agree with each other to form a commonwealth, a view clearly in accordance with the idea that liberty is best protected in separate and independent nation states. And in his Letter Concerning Toleration, he argued that sharp limits restrained government power from infringing individuals’ inalienable right to worship God as conscience dictates.

Is Locke’s “a shockingly insufficient basis for understanding political reality,” as Hazony claims? Locke’s liberalism was certainly not without its instabilities and blind spots, but understanding the fullness of political reality was not his aim in the Second Treatise. His aim instead was to explain how individuals who are by nature free and equal—that is, not subject to any human authority to which they have not consented—can nevertheless legitimately form governments that protect individual freedom by making and enforcing laws binding on all.

Later on, Locke’s ideas were developed in different directions. The American founders crafted a constitution limiting government for the sake of free and equal individuals who would assume responsibility for their families, participate in local civic and political affairs, and worship freely without imposing their religious beliefs on others. By contrast, the leaders of the French Revolution, embracing Locke’s premise that human beings were by nature free and equal, concluded that only an unlimited state could release the people from the chains of ancient beliefs and practices, particularly religion.

In Reflections on the Revolution in France, the Whig statesman Edmund Burke laid the foundations for that branch of modern conservatism devoted to the conserving of freedom. While agreeing with the revolutionaries in Paris that freedom was the proper aim of politics, Burke lambasted the doctrine according to which the sustaining non-governmental sources of liberty—family life, local associations, moral and intellectual virtue, customs and traditions, and religious faith—were to be seen as adversaries of liberty.

This left-wing, freedom-imperiling branch of the tradition of freedom is the one that Hazony condemns in excoriating Locke and by extension the entirety of the liberal tradition. The conservatism or “classical nationalism” with which Hazony aligns himself corresponds, more or less, to the right wing. By suggesting that modern conservatism is instead essentially biblical in its provenance, he thus obscures its distinctiveness, not least in its dedication to conserving that form of freedom powerfully outlined by Locke.

Third, Hazony’s contention that the modern argument for nation states is primarily a Protestant—and biblical—construction imprudently restricts the reach of any potential political coalition to recover and preserve it. In our age, divine revelation has become questionable in a way it wasn’t during the time of King Solomon or, for that matter, in the middle of the 17th century when European states brought the Wars of Religion to an end by hammering out the Peace of Westphalia.

Today, Hazony observes, “Millions of people, especially outside the centers of elite opinion, still hold fast to the old understanding that the independence and self-determination of one’s nation hold the key to a life of honor and freedom.” So they do. In the West, however, many of these millions do not hold fast to biblical authority, to say nothing of those inside the centers of elite opinion who emphatically reject all things biblical. By recognizing the case for free and independent nation states developed within the modern tradition of freedom, Hazony could substantially expand the coalition he rightly wishes to form.

Yoram Hazony shows that the Bible has much to teach friends of freedom in the face of the threat posed by contemporary political tendencies. It does indeed—but the aim should not be to restore a biblical politics. Rather, it should be to reform liberal democracies in light of the best of the modern tradition of freedom so that, within the limits set by their justly circumscribed powers, they will be open to biblical wisdom and disposed to cultivate citizenries capable of cherishing it.