Edward Rothstein opens his essay on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition, Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven, with a well-deserved tribute to the gorgeousness of the objects on display and the splendidly illustrated catalogue. He then goes on to query whether the exhibition and catalogue really reflect the political, economic, artistic, and religious realities of medieval Jerusalem. Having read the catalogue and Rothstein’s criticisms of it, I am in broad agreement with him, and I found his analysis more interesting and more persuasive than the catalogue’s Pollyannaish presentation of medieval realities.

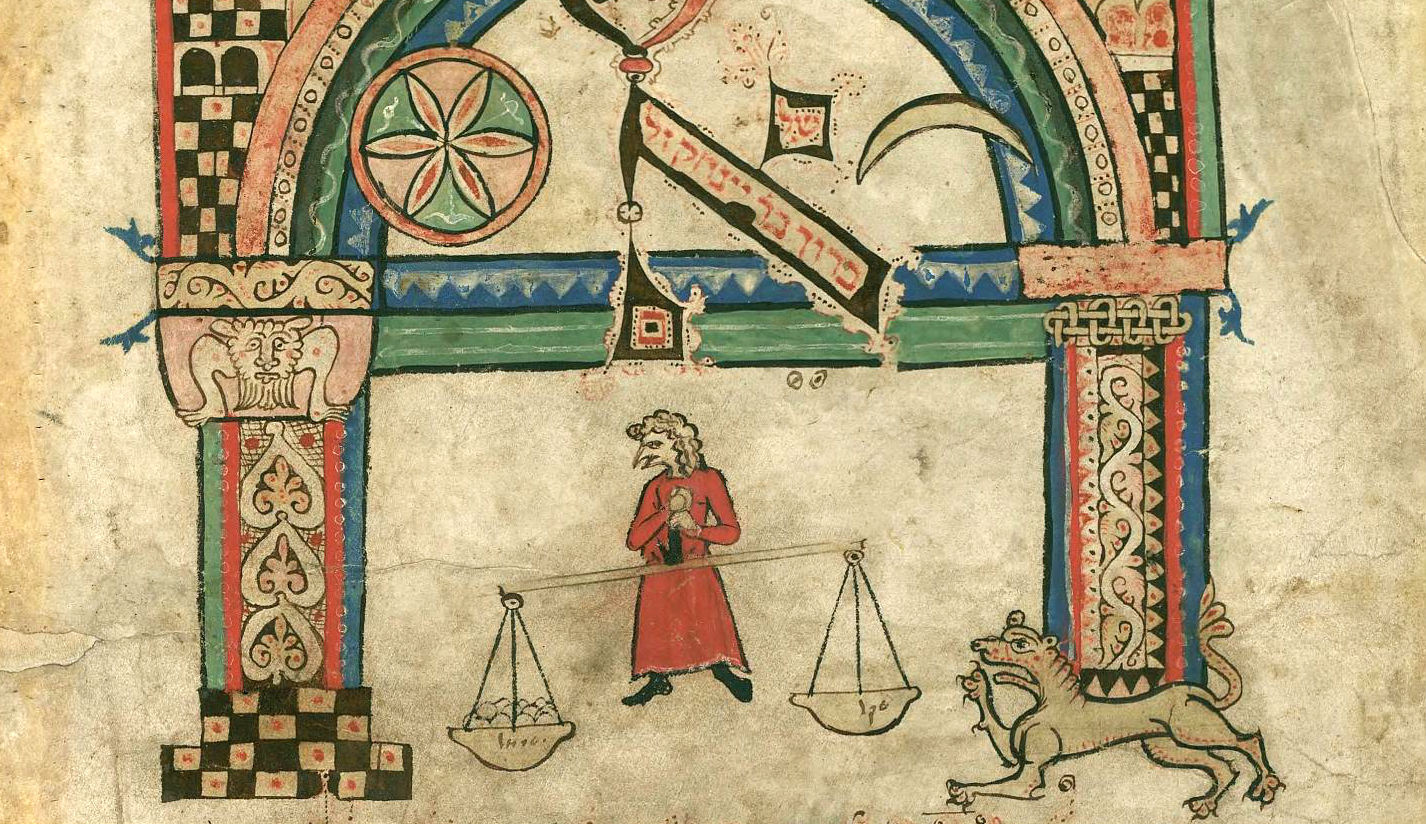

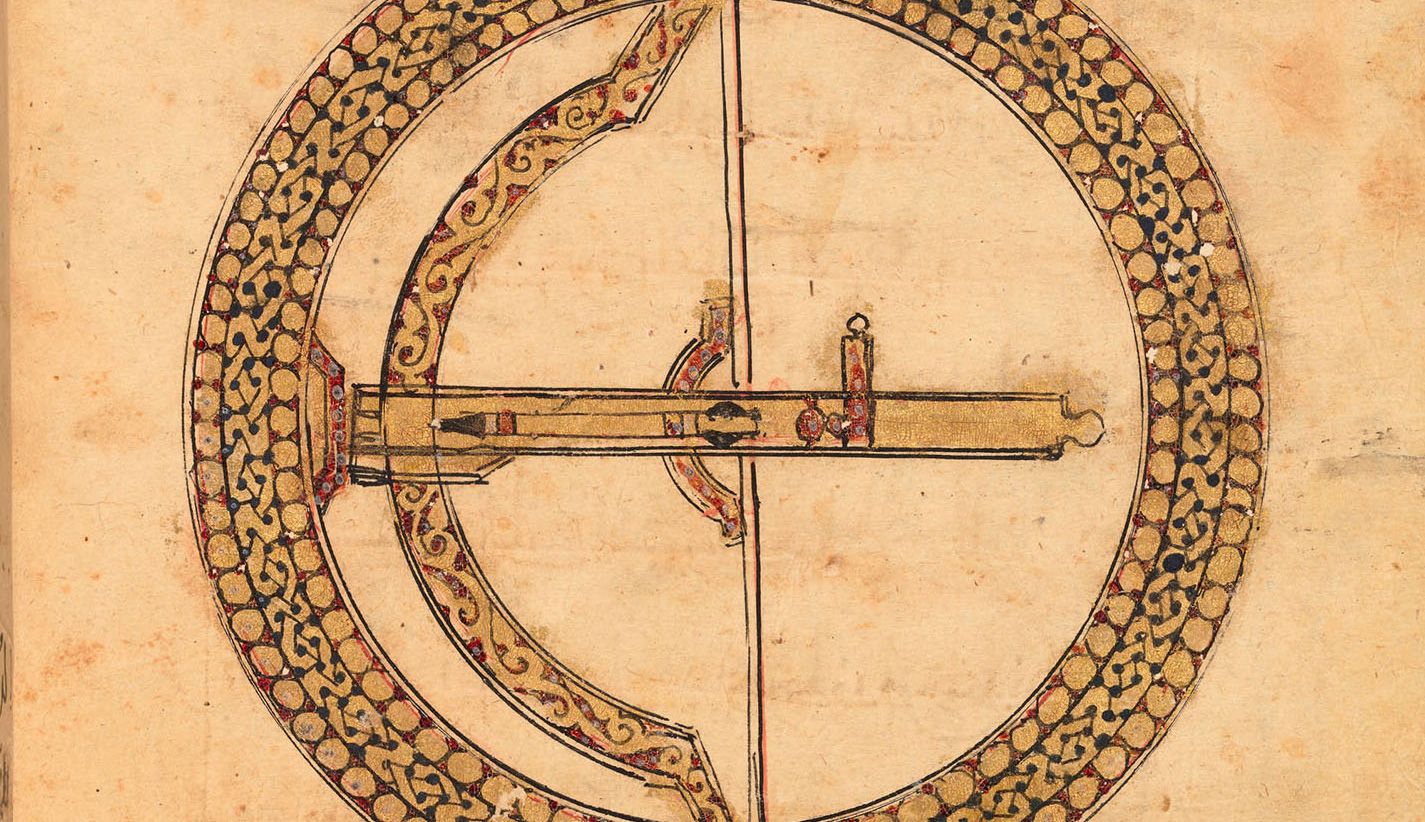

Today the stress on relevance and diversity is the bane of pop-history writing. Popular historians, historical novelists—and museum curators?—are reluctant to acknowledge how nasty things could be in the Middle Ages. The Met’s exhibition presented Jerusalem under the rule of the Fatimids, Crusaders, Ayyubids, and Mamluks as home to “multiple competitive and complementary religious traditions.” The place was allegedly a cultural melting pot and a perfect example of the convivencia in which Christians, Muslims, and Jews all benefited and Jerusalem’s local economy thrived, something that might be suggested by the marvelous artefacts on display: illuminated manuscripts, astrolabes, enameled glassware, and so forth.

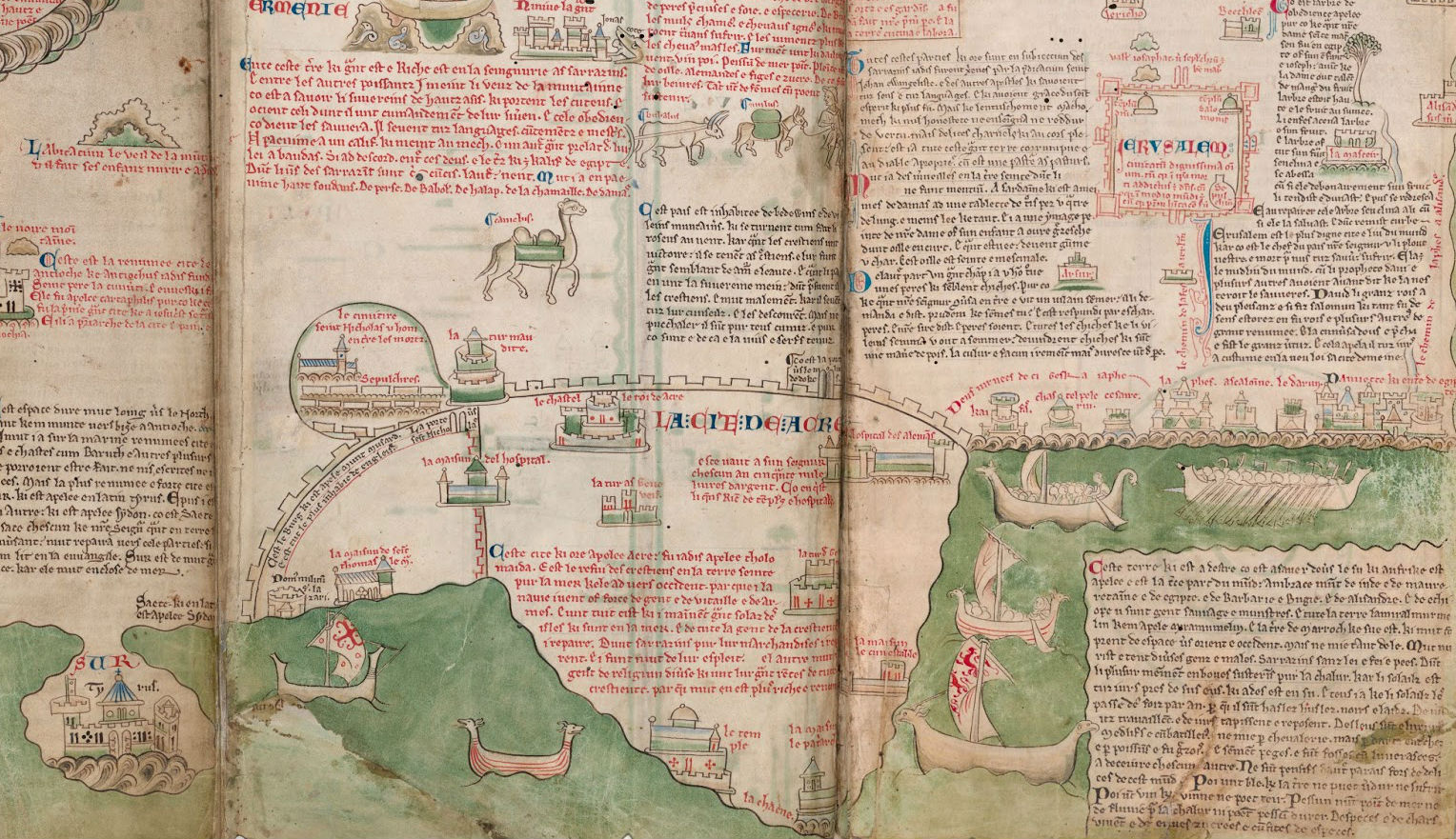

But, as Rothstein points out, most of the things on display were produced elsewhere—in Cairo, Damascus, France, Spain, Germany—and some were never available in Palestine. Having consulted written sources for the period, I think that what should have been displayed as local produce was soap, olive oil, crude glassware, maybe leatherwork, and not much else. There were three arcaded markets in Jerusalem; the central one bore the unenticing name, “The Street of Evil Cooking.”

It’s true that other and more exciting stuff was available in the spring and summer seasons when Christian pilgrims were in town, though traders evidently brought in the goods from elsewhere. Nompar de Caumont, who was in Jerusalem on a pilgrimage-cum-shopping spree in 1419, just two decades after the Met’s cutoff date of 1400, kept a long list of his purchases in the city—much too long to be fully enumerated here but including a Damascus textile of red and gold, an ivory chaplet, four white silk belts, 33 silver rings that had touched the Holy Sepulchre, five “serpentines” that were efficacious against snake venom, two pairs of gilded spurs that had touched the Holy Sepulchre, five Turkish knives, six pairs of chamois leather gloves, twelve more Turkish knives, a bone of Saint Barnabas, and a bone from one of the 11,000 virgins.

Things may have deteriorated later, for Conrad Grüneneberg went around the markets of Jerusalem in 1486 without finding anything he thought worth buying. It could be that recent Bedouin depredations had temporarily disrupted the local economy; for centuries, Jerusalem and its environs had been intermittently subjected to such attacks. The place was a one-horse-town dependent on the pilgrim trade, but sometimes the pilgrims did not come, or the local Bedouins had looted the city. In 1260, as Rothstein notes, Abraham Abulafia found it impossible even to reach the city. I might add that genizah sources show earlier Jews finding it similarly impossible to reach Jerusalem in the years immediately before the coming of the First Crusade, when fighting in Palestine between the Fatimids and Seljuks was at its height.

Nor, contrary to the exhibition’s thesis, was Jerusalem always a place where the three faiths, let alone different factions within any of them, harmoniously complemented one another. At the end of the 10th century, under Fatimid rule, Rabbanite Jews, in addition to feuding with local Karaites, were being persecuted and mulcted by the Muslim authorities. As they wrote in a letter soliciting the help of other Jewish communities: “Life here is extremely hard, food is scarce, and opportunities for work very limited. Yet our wicked neighbors exact exorbitant taxes and other ‘fees.’” After the Crusader occupation in 1099, Jews were forbidden to reside in the city (as were Muslims), and only started to return after 1187 when it surrendered to the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin.

A literary curiosity may be noted here. The 15th-century local historian Mujir al-Din al-‘Ulaymi managed to produce a lengthy and detailed history of Jerusalem, Uns al-Jalīl bi-Tārīkh al-Quds wa’l-Khalīl, without once mentioning either the Christian pilgrims or the Jewish community. This only underlines the fact that the Jewish community in Jerusalem in the Ayyubid and Mamluk period was neither numerous, nor wealthy, nor intellectually distinguished. The main Jewish settlements in the area were in Tyre, Acre, and Ashkelon. Later, in the Ottoman period, the Jews of Safed in the Galilee would produce, in figures like Joseph Caro, Isaac Luria, and others, a varied body of literature that was both intellectually impressive and spiritually compelling.

The Christians of the Crusader Kingdom also did not distinguish themselves intellectually. The one exception was the great, Paris-educated historian William of Tyre, who presumably spent most of his time in that city in his capacity as archbishop. The brilliant 12th-century scholar and mathematician Adelard of Bath is known to have visited the Crusader states, but it is not recorded what he did there or to whom he talked, or whether he bothered to visit Jerusalem. As Joshua Prawer notes in The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: European Colonialism in the Middle Ages, “it is obvious that the Holy Land under the Crusaders never became a center of original creativity.”

Edward Rothstein observes that the Met’s exhibition and catalogue pay considerable attention to the holy war waged by the Christian Crusaders but skimp in their account of Islamic jihad. Here is what the curators, Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb, have to say about the evolution of the idea of jihad during the period of the Crusades:

It is in this same period that Islamic scholars increasingly began to reinterpret Quranic discussion of jihad, or struggle, to embrace the concept of fighting as religious duty, rather than an inner struggle or a defense of a community. This development is generally understood to have been fueled by Crusader incursions. [Emphasis added.]

This is apologetics, not history. The idea of jihad as “inner struggle” is a belated Sufi gloss. From the beginning, most medieval Muslims understood the various Quranic injunctions as entailing an armed struggle to bring the whole world under the rule of Islam. According to this view, the polytheists should be exterminated and the Christians and Jews obliged to pay a poll tax until they converted.

Long before the coming of the Crusaders, the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs had led annual or biannual aggressive campaigns against Byzantium and other non-Muslim regimes. During the Muslim campaigns against the Byzantines, Greater Syria was known as pre-eminently the territory of jihad. After the decline of the Abbasids, the 10th-century Arab Hamdanid dynasty, based in Aleppo, revived the prosecution of aggressive jihad. In the 11th century the Turkish Seljuks presented their war against the heretical Fatimids as a jihad.

Enough. The Met’s presentation of Jerusalem as the capital of a culturally vibrant La La Land is seductive, but its seductions should be resisted.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Jerusalem, Religion & Holidays