Edward Rothstein’s incisive discussion of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven confirms my own impressions of the show, about which I wrote in a piece for the Federalist. Here I want to make even more emphatic Rothstein’s grasp of the issue at stake in an exhibition whose overall tendentiousness began at the starting gate.

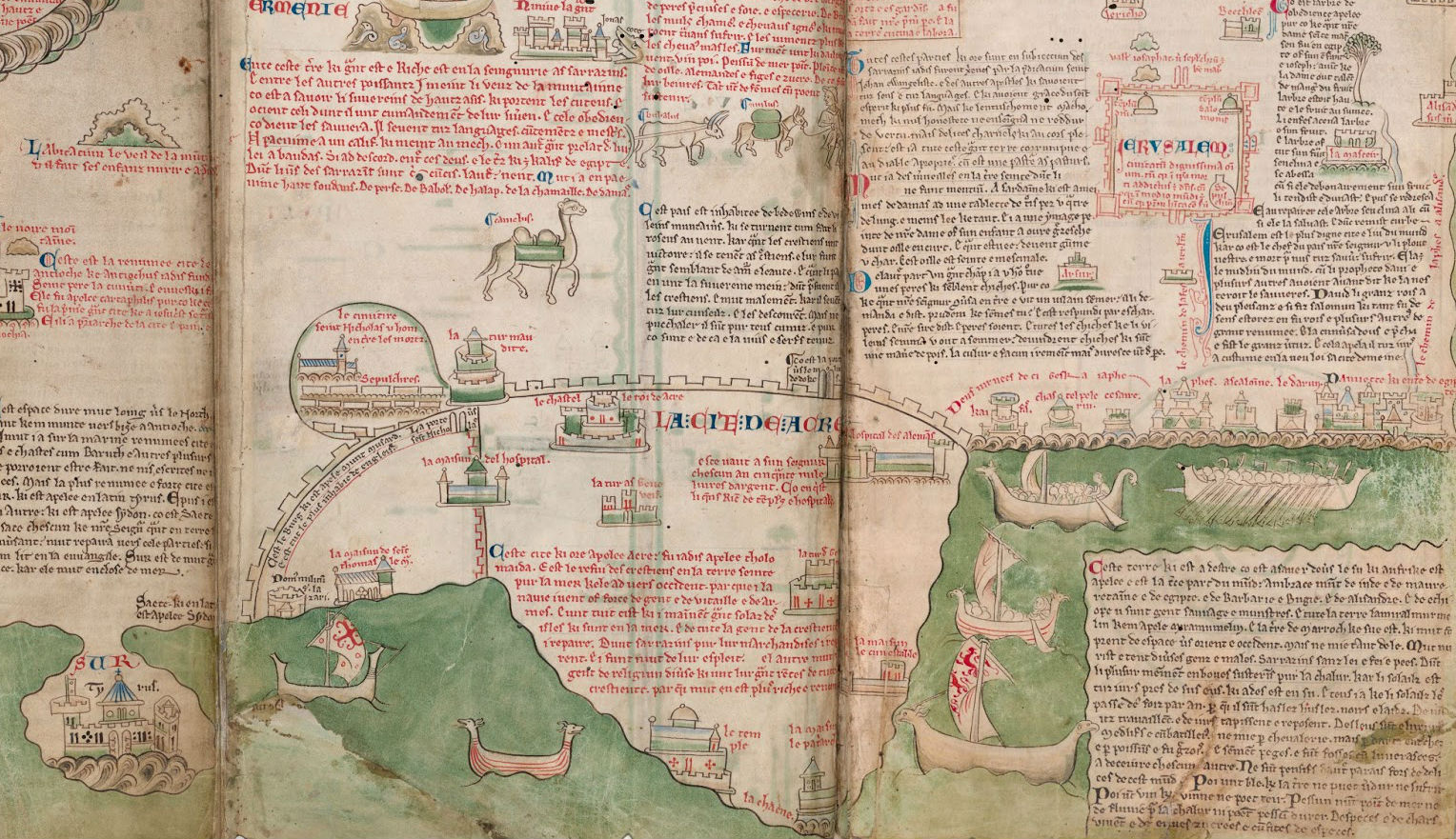

An outsized projection of the Dome of the Rock commanded the exhibit’s entrance hall, eclipsing an ensemble of smaller images of other sites. Built at the end of the 7th century in the appropriated style of a Byzantine martyrium, the Dome, then as now, stood as an architectural symbol of Islamic ascendancy.

Starting from that point, and threaded throughout the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, was further evidence of this assertion of privilege. The museum’s pageant of artifacts, undeniably beautiful, no doubt accounted for the rapturous and almost universal applause that greeted the exhibition. But the Met, after all, has been in show business since its former director Thomas Hoving made the mummies dance 40 years ago, and spectacles are its meat and potatoes. In this case, the aesthetic dimension was in the service of a tutorial.

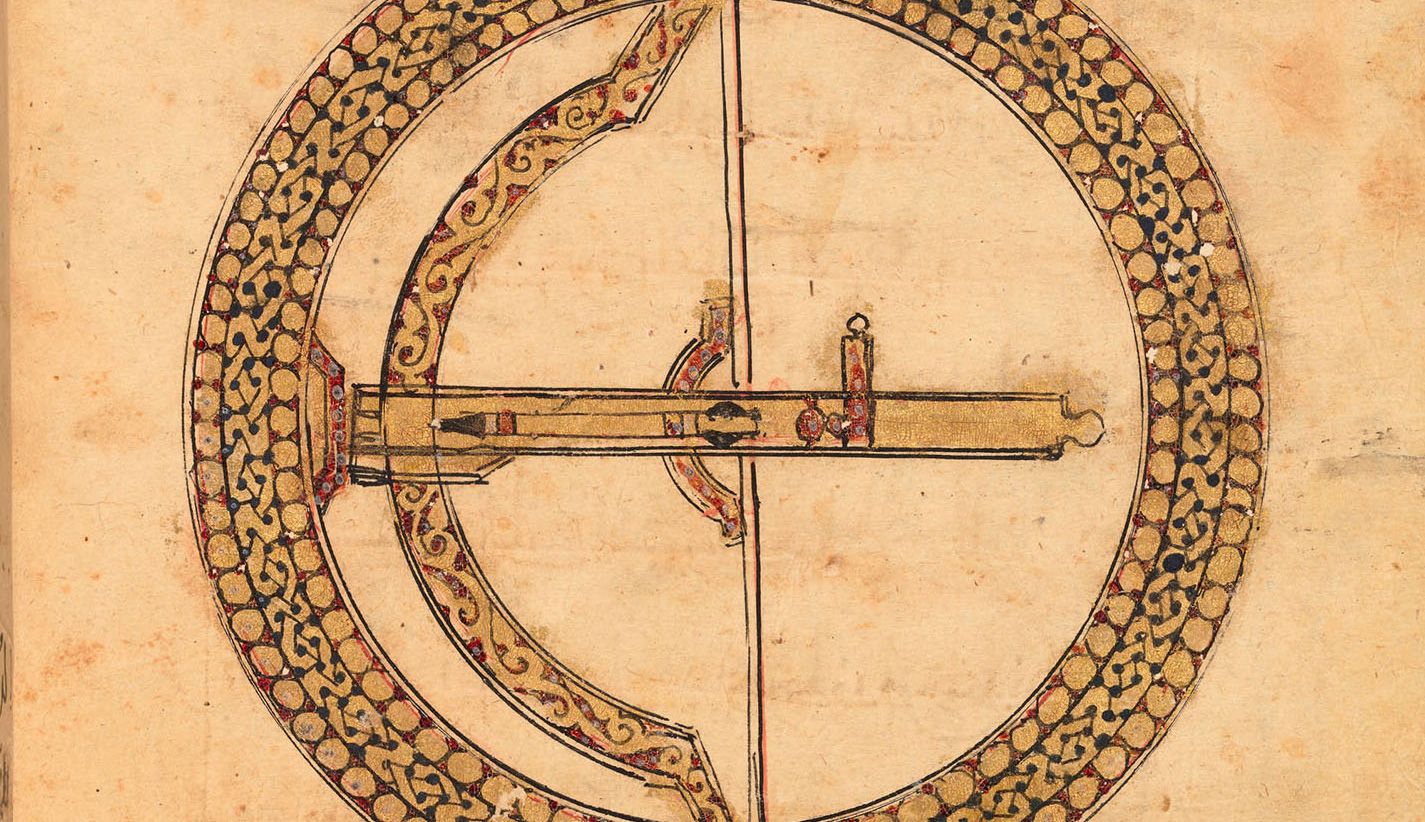

In the Metropolitan Museum’s telling, medieval Jerusalem was a light to the nations, a showcase of interfaith comity and a multicultural Arcadia that flourished under the open-minded tolerance of Islamic domination. (And by the way, the cuisine was first-rate.) Here was Islamic rule selectively cleansed of its imperialism, brutality, absolutism, and institutionalized subjection of non-Muslims. Shariah with its barbaric punishments disappeared. Gone were the humiliations and burdens of dhimmitude. Gone, too, the debased status of women and the slave market extant in every city of the medieval Islamic world.

To squeeze this dormouse into a teapot, the show’s curators, Barbara Boehm and Melanie Holcomb, separated “culture” from its wellsprings in politics. As they write in the catalogue:

Suppose we set aside political history as a means to define cultural history so that we could better explore the variety, richness, interconnectivity of the city, its people, and its arts?

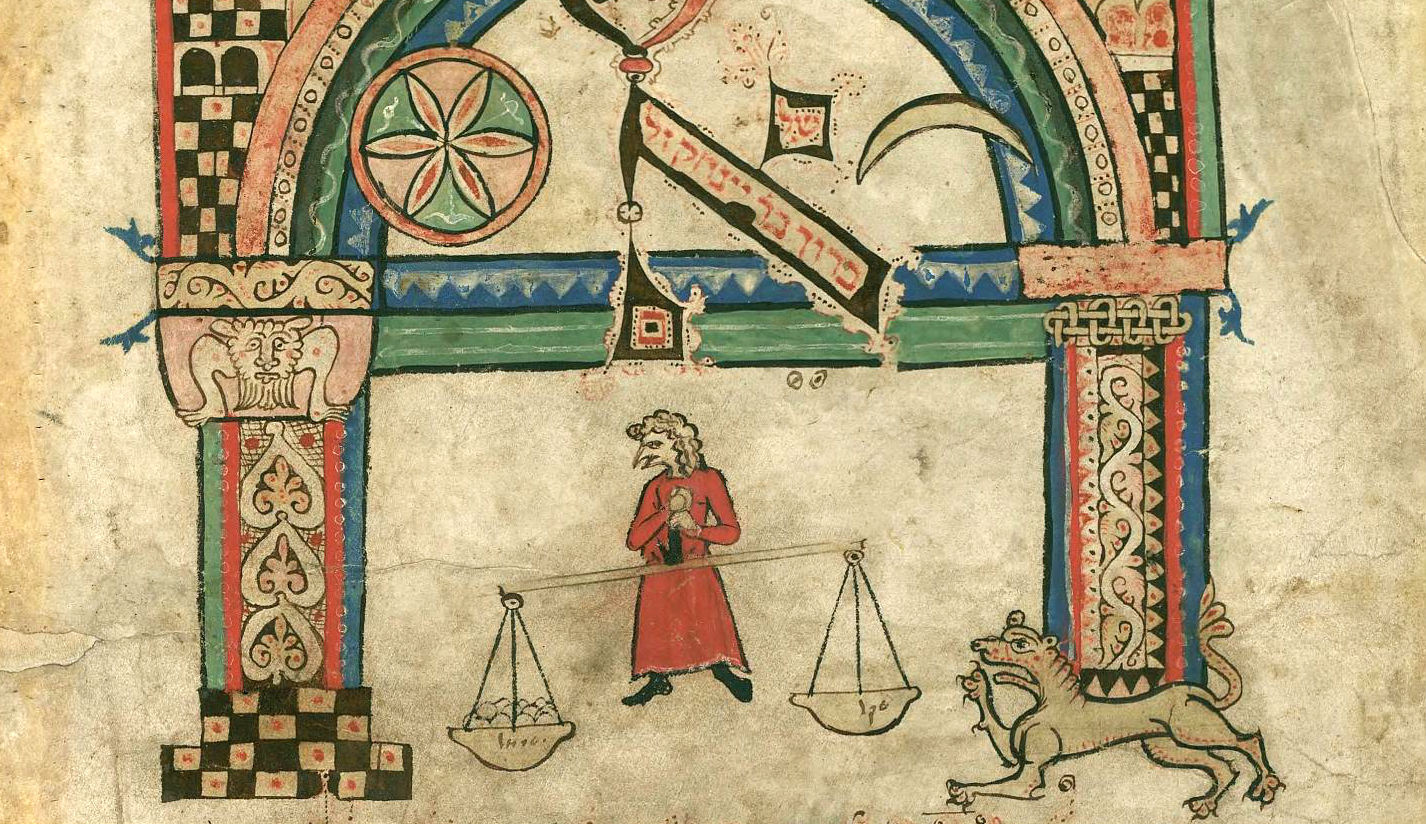

The word interconnectivity signals the curatorial effort to mask what were centuries of struggle for power and civilizational survival—by persecuted Christians under Islam, and by perennially endangered Jews under both Christians and Muslims. All of this was subordinated to a softened, idealized, and anachronistic picture of Islamic order. Catalogue entries recount the past in terms of modern sensibilities, with a narrative that cherry-picks vignettes of atypical elites—poets and scholars on “the flourishing academic scene”—to portray the Holy City as a shrine to interethnic inclusion and “fluid religious identity.” Muslim rulers are depicted as pluralists, and Islamic Jerusalem as offering a striking contrast to “Venice, Rome, Paris—none of [which] tolerated the same degree of religious diversity.” Playing underneath is a revisionist historical subtext: Christians and, especially, Jews hold no greater historical claim to Jerusalem than do Muslims, and may hold a weaker one.

Crucial factual omissions presume an historically insensitive audience. The wall blurbs opened with this: “Beginning about the year 1000, Jerusalem captivated the world’s attention as never before.” True, but omitted was the reason: in 1009-10, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the demolition of all synagogues and churches in Palestine, Egypt, and Syria, including Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Decades later, following centuries of Islamic assault on what was then Christian territory, the city’s tattered condition supplied one of the final triggers leading to the Crusades.

The show’s continuing tutorial portrayed Christian Crusaders as unprovoked aggressors who conquered and claimed, while Muslims would later reclaim and retake. That reversal conforms to the tropes of our culture, eliciting assent from the many who identify the totality of the Crusades with unsanctioned—and often anti-Semitic—excesses in a cruel and bloody age. In fact, however, the Crusades, like the reconquista in Spain, began in response to Muslim invasion and subjugation.

The exhibition’s drumbeat of phrases like “Christian warriors” and “Crusader occupation” also played on ignorance of the fact that the Crusades, among the most misunderstood events in Western history, were unsuccessful—and thus, consequently, irrelevant to Muslims until the collapse of the Ottoman empire. As the historian Thomas Madden has written:

[T]he Crusades were virtually unknown in the Muslim world even a century ago. The term for the Crusades, harb al-salib, was only introduced into the Arab language in the mid-19th century. The first Arabic history of the Crusades was not written until 1899. . . . In the grand sweep of Islamic history, the Crusades simply did not matter.

They did not matter, that is, until they became useful to 20th-century Islamists and Arab nationalists who shared a desire to rid the Middle East of “colonialist” European powers. But whatever else they might have been, the Crusader kingdoms themselves were not colonial ventures. Unconnected to any foreign state, they were embattled enclaves within the Muslim world. Today they have been resurrected as weapons with which to bludgeon Israel and the West.

Edward Rothstein notes in particular the museum’s reluctance to affirm Jewish historical attachment to the Temple Mount. As inhabitants of Jerusalem, Jews were almost as “absent” from this exhibition as was the biblical Temple. They appeared as travelers, barely as residents. The Jews of Jerusalem, we were told, were among its poorer citizens and “in some cases makers of goods.” That dismissal ran in tandem with the meta-narrative structured around an overriding struggle between the West and its Islamic challenger.

Pertinent to what Rothstein calls the Met’s “refusal to confront history” is the proselytizing vocation of one of the museum’s trustees. Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah, a Kuwaiti princess, is director and co-founder of Kuwait’s Dar-al-Athar al-Islamiyyah (DIA), a museum created to house the al-Sabah collection of Islamic art, now on permanent loan to the Kuwaiti state. The princess travels Europe and the United States bearing the gospel of Islam’s refinements, using art to neutralize unflattering images of Islamic culture.

The flipside of that enterprise, much in evidence at the Met’s Jerusalem 1000-1400, was the demotion and deprecation of the culture of others—if not, in the case of the Jews, a virtual denial of their historical attachment to their city. In this light, Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven also contributed toward the by now global campaign to undo the state of Israel.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Jerusalem