Last fall, the art historian Victoria C. Gardner Coates published an op-ed article in the Wall Street Journal suggesting that the utopian multicultural paradise imagined by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven was being used to promote a particular political position concerning the status of today’s Jerusalem. The exhibition functioned, in her words, “as a highbrow gloss on the movement to define Jerusalem as anything but Jewish, and so to undermine Israel’s sovereignty.”

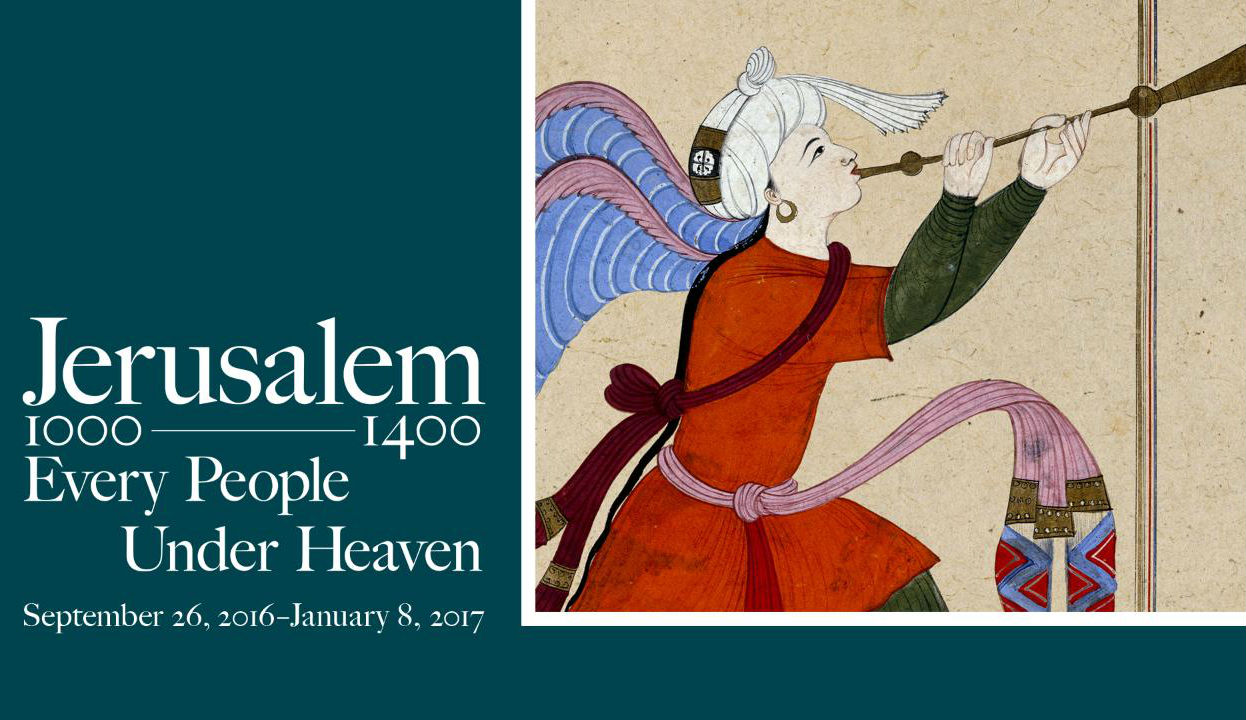

Coates’s article provoked a letter to the editor from Thomas P. Campbell, the Metropolitan’s director and chief executive officer (until his sudden resignation in late February). Objecting to Coates’s “extraordinarily narrow perspective,” Campbell assured readers of the Journal that, far from engaging in an anti-Israel “conspiracy”—his word, not hers—the museum’s purpose in mounting this “unprecedented gathering of masterpieces from the three Abrahamic faiths” was simply to “reveal the richly intertwined nature of these various aesthetic traditions at a fascinating moment in Jerusalem’s history.”

“If anyone has chosen to politicize the exhibition,” Campbell concluded, “it is Ms. Coates.”

I have no reason to doubt the sincerity of Campbell’s belief in the innocence of his museum’s exhibition, a belief shared by almost all reviewers. On certain subjects, when historical facts and their implications threaten to disrupt one’s more heavenly and comforting visions, the tendentious aspects of such visions simply become invisible: beyond notice, and certainly beyond argument. All the more reason, then, for me to thank the three respondents to my essay—Robert Irwin, Steven Fine, and Maureen Mullarkey—for making even more palpable the weighty historical facts that prove the illusion, or delusion, in Thomas Campbell’s blithe conception of that “fascinating moment in Jerusalem’s history.”

The Met was intent on showing medieval Jerusalem to be, in Irwin’s words, “the capital of a culturally vibrant La La Land,” and no counter-evidence—abundant examples of which are provided by Irwin in his learned and lively response—was permitted to get in the way. Moreover, just as the show’s positive vision of a medieval paradise was open to serious question, so too was its vision of the age’s stock villains; Mullarkey’s acute points about the show’s notion of the singular evil of the Crusades and of Christian rule in the Holy Land provide fodder for a much more extended inquiry.

Perhaps most surprising is how thoroughly the Met ended up distorting not just a proper historical perspective but a proper aesthetic perspective as well. Given how few artifacts in the show were actually from Jerusalem, and given that fewer still could even remotely be considered “masterpieces” (Campbell’s inflated term), the Met cannot be said to have demonstrated, on its own terms, how great cultural glories arose out of this presumed multi-faith experiment in convivencia.

Steven Fine suggests that the desire to conjure up a world of multicultural tolerance—and, in particular, to whitewash the more painful truths of Jewish historical experience—is not unique to this exhibition but has also characterized others at the Met (and elsewhere). In part, this may be owing to the Met’s tenaciously held belief in the salvific powers of art to transcend all differences and to evoke the humanly universal. Ironically enough, one of the achievements of the Met over recent decades has been to keep alive the quasi-religious aura that still clings, however tenuously, to art—a remarkable achievement in an age intent on reducing art to yet another species of politics waged by other means. Campbell’s charge of “politicization” against Victoria Coates (which he would no doubt apply to my essay as well) is partly such a defense of aesthetic autonomy, and a defense with which I sympathize.

But in the case of this exhibition, not only did much of the art fail the test of aesthetic distinction; in addition, the realm of the aesthetic was manifestly harnessed to serve other, non-aesthetic purposes. Mullarkey discerns here the strong influence of a particular Met trustee: namely, Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah, a Kuwaiti princess who, she notes, is “director and co-founder of Kuwait’s Dar-al-Athar al-Islamiyyah (DIA), a museum created to house the al-Sabah collection of Islamic art.” Perhaps so; but the impulse behind the show extended greatly beyond a single person’s proselytizing influence. Indeed, it can be seen at work in a whole series of cultural accommodations in the decade-and-a-half since September 11, 2001.

To put it bluntly, the attacks of that day and many more thereafter led to a subtle and peculiar form of Western apologetics. No matter how often the terrorists themselves and their supporters insisted on connecting their deeds with Islam itself, Western political figures and cultural institutions not only denied any such association but deliberately initiated celebrations of Islam and its achievements. These initiatives were in turn quickly and widely honored as embodying a properly enlightened perspective.

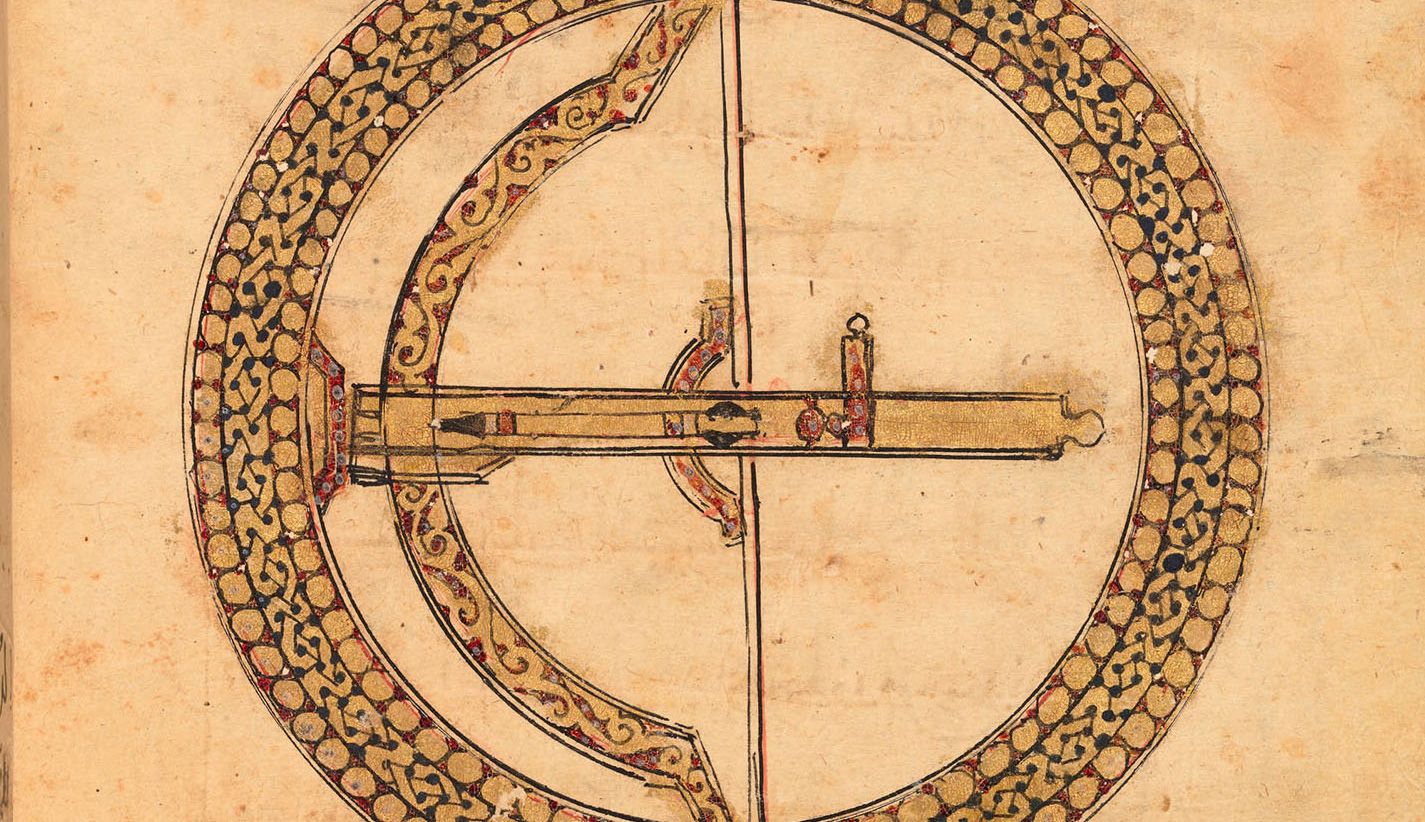

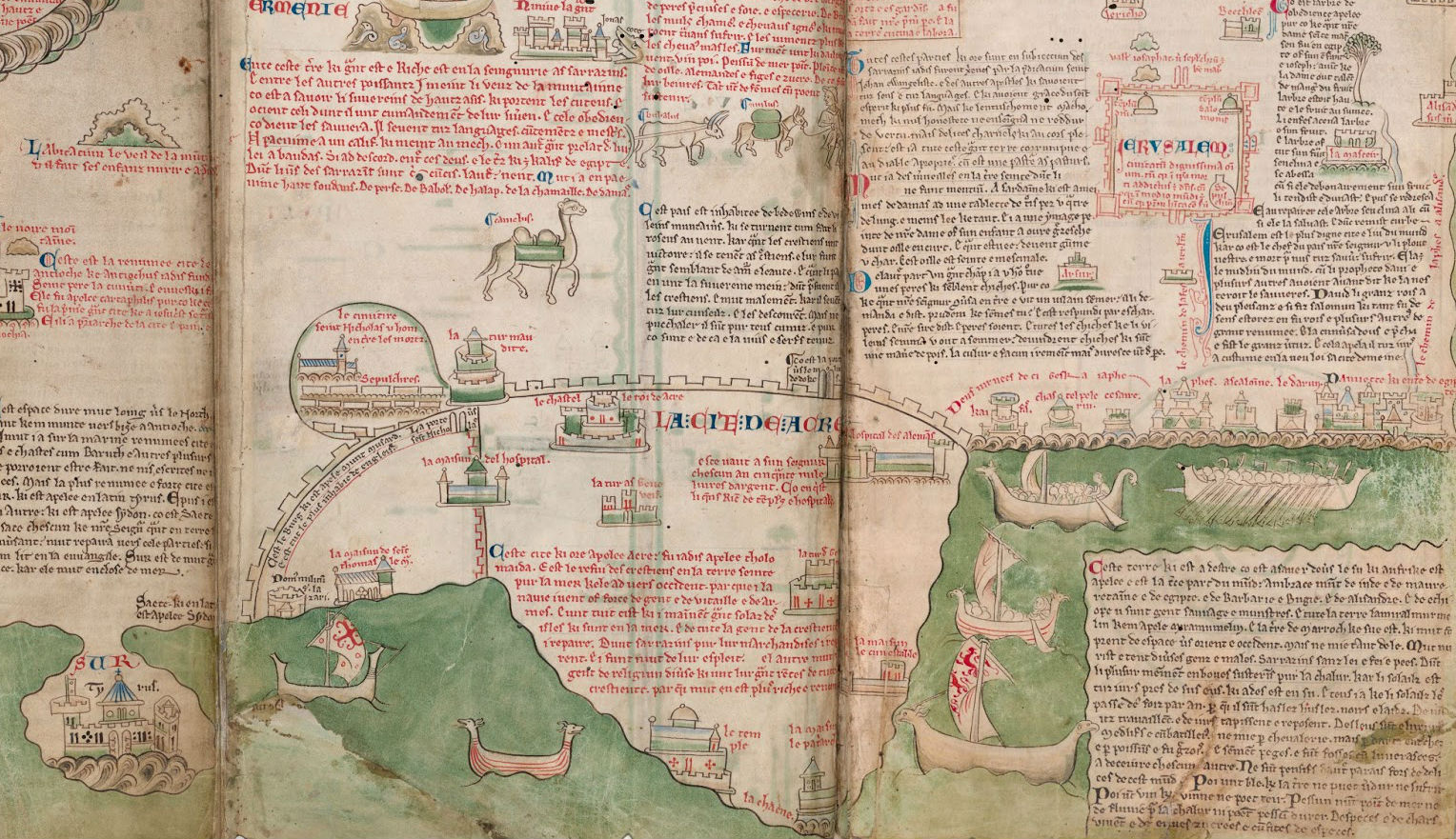

Thus, in France in 2002, Prime Minister Jacques Chirac proposed that the Louvre museum create a post-9/11 department of Islamic art in order to demonstrate “the essential contribution of Islamic civilizations to our culture.” In 2004, France’s minister of culture, Jean-Jacques Aillagon, told the New York Times, “Obviously, this [emphasis] has a political dimension. It’s a way of saying we believe in the equality of civilizations.” In 2007, the Met in New York did its part with an exhibition lauding the interchange of cultures in Venice and the Islamic World 828-1797. In 2011, after eight years of planning, the Met opened a new (and quite beautiful) 19,000-square-foot revision of its Islamic galleries at a cost of some $50 million. In 2016, another such effort came in Court & Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs—an Islamic dynasty also relevant to our current subject because after 1073 the Seljuqs controlled Jerusalem for a brief but bloody interval.

So overriding has been the impulse to boost and to extol that it has almost always necessitated a greater or lesser degree of obfuscation, camouflage, and distortion. As a critic for the New York Times during most of this period, I came up against the phenomenon in the most surprising places. In the summer of 2002, at the Lincoln Center Festival, traditional Iranian folk dramas (Ta’ziyeh) were presented. These ceremonial tales of massacre and martyrdom are related to the battles that led to the founding of Shiite Islam and were traditionally associated with much bloodletting. At Lincoln Center, however, they were conspicuously presented without benefit of translation or full explanation, the action on stage being instead homogenized to create a deceptively ecumenical event in which it greatly helped for the audience not to understand precisely what was happening.

More blatant was a 2010 show about Muslim science called 1001 Inventions at the New York Hall of Science. A version of this exhibition had previously been presented at the United Nations and the British parliament, and had toured British schools. It claimed to document how a millennium-long “golden age” of Islamic science, lasting into the 17th century, had anticipated the great inventions and discoveries of the modern Western world, which had duly proceeded to minimize or ignore its indebtedness. Created by the blandly named Foundation for Science, Technology, and Civilization in London, whose goal is “to popularize, spread, and promote an accurate account of Muslim Heritage and its contribution,” the exhibition was rife with overstatement and spin—and promotion. Along the way, it dutifully praised the multicultural aspect of its alleged golden age of science while actually undercutting non-Islamic contributions at every turn.

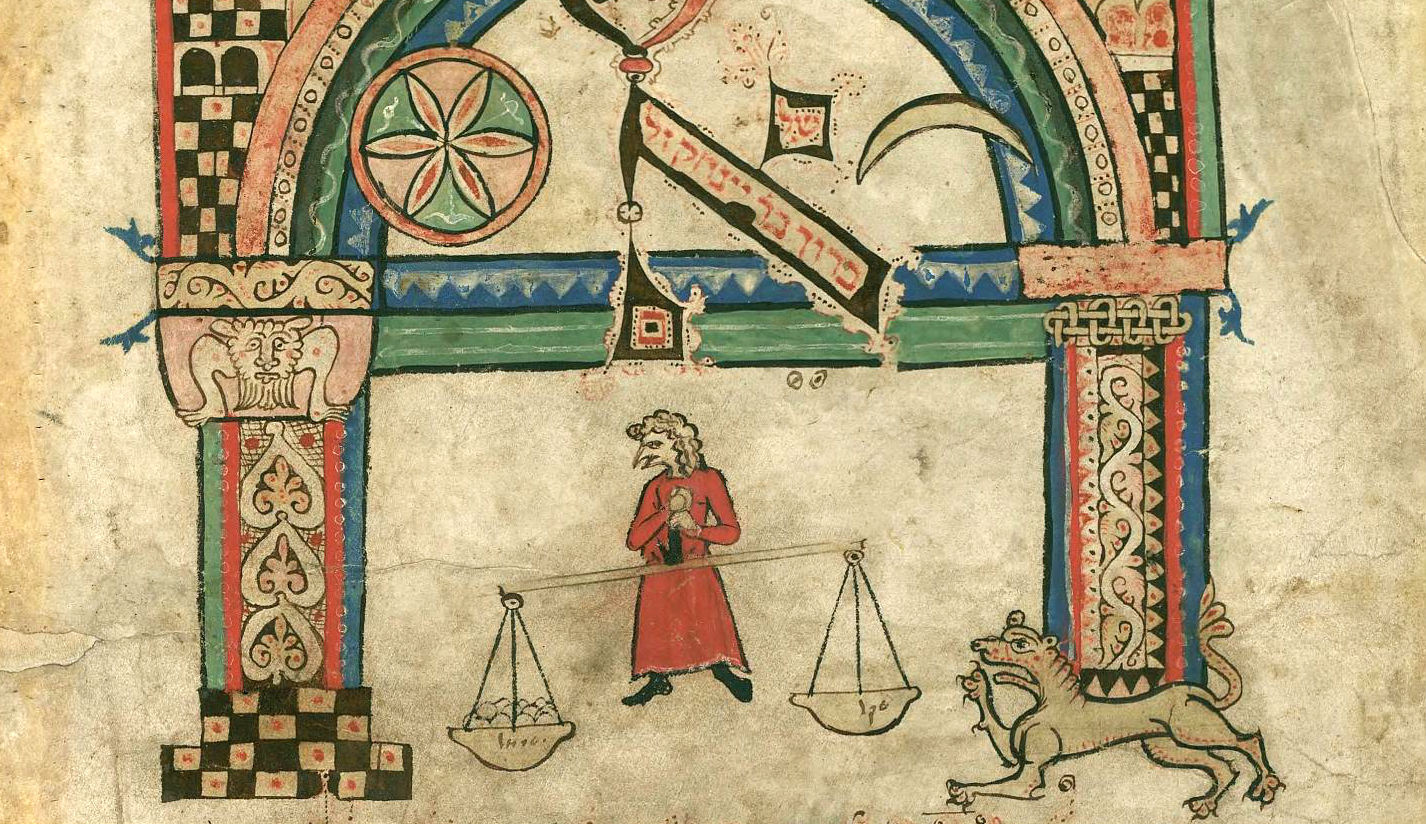

There was also a series of exhibitions in which the promotion of Islam itself was subsumed under the concept of ecumenism: specifically, of three allegedly “Abrahamic faiths” so closely tied together that harmonious relations among them should be considered the natural state of affairs. A main sponsor of one such exhibition at the New York Public Library in 2010, Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam (which grew out of a similar exhibition in 2007 at the British Library), was the Coexist Foundation, created in order “to promote better understanding between Jews, Christians, and Muslims.” But in order to reach this goal, the displays stripped away any important sense of how the three faiths differed, and in particular how the two successor faiths, Christianity and Islam, aggressively distinguished themselves from each other and from their shared ancestor. One point of this exercise in supposed mutual fructification was to establish Islam’s close connections to Western traditions while also distancing it—as one catalog essay made clear—from its association with terrorism. (In 2012, these loaded themes were more subtly handled in the Jewish Museum’s Crossing Borders: Hebrew Manuscripts as a Meeting-Place of Culture, another ecumenical exhibition of texts based on a 2009 exhibition at Oxford University.)

In this light, the Met exhibition, with its nearly explicit celebration of Islamic rule in medieval Jerusalem accompanied by ostinato invocations of ecumenism, is of a piece with other post-9/11 events of a similar kind and needs to be seen in that context. Nor, Thomas Campbell’s protestations to the contrary notwithstanding, can it be treated as completely naïve. To take one salient example: in conjunction with the exhibition, the Met’s performing-arts arm, MetLiveArts, commissioned an oratorio from a composer, Mohammed Fairouz, whose website notes his “cosmopolitan outlook” and eagerness to “promote cultural communication and understanding.” The oratorio, Al-Quds: Jerusalem, set to poetry by Naomi Shihab Nye, was given its premiere on December 6 in a performance by the Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr.

As it happens, upon seeing the oratorio’s text, a member of the orchestra’s board, Glenn Schoenfeld, resigned rather than allowing himself to be associated with the performance. A brief glance at the poetry suggests what prompted so dramatic a response.

The first poem, “Jerusalem,” begins, “Not your city—everyone’s city.” Since the “you” addressed here is surely meant to be mainly identified with Israel, the message being driven home is the same message that Victoria Coates found to be indirectly implied by the exhibition and whose presence was explicitly denied by Thomas Campbell. The second poem, “How Long Peace Takes,” ends as follows: “As long as anyone feels exempt/ or better and one pain is separate/ from another and people are pressed flat/ in any place/ And longer/ If every day the soldier slaps/ another cousin’s face.” In other words, the absence of peace in Jerusalem is traceable to one source: the unnamed group that “feels exempt” or “better” than others, that treats its own pain as humanly “separate” from the pain of others, that presses those others “flat,” and that permits or encourages its soldiers to slap their faces. (For some reason, no evenhanded mention is made here of those who drive trucks or automobiles into crowds, or those who attempt to behead passersby, or those who officially celebrate these forms of Jerusalem street life.) The final poem in the oratorio, “Keys,” then invokes a central image of Palestinian refugee culture: “We kept our keys,” it begins. But “the keys will turn again,” and once they do, the doors will “open wide”: “Welcome welcome welcome/ everyone inside.”

Here the Met’s vague ecumenisms were made literal. Presumably, when the keys “turn again,” the arrogant occupying party—identified in familiar anti-Semitic tropes—along with its slap-happy soldiers, will have been suppressed, defeated, or eliminated. Only then will openness and tolerance be felt again, and only in that way will “everyone” really be welcome—just as “everyone under the sun” was welcome in the Met’s roseate portrait of golden-age Jerusalem under Islamic rule. In one and the same spirit the museum envisioned the past and the poet envisions the future, embracing and exploiting the vocabulary of openness in the name of something very different.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Jerusalem, Metropolitan Museum of Art