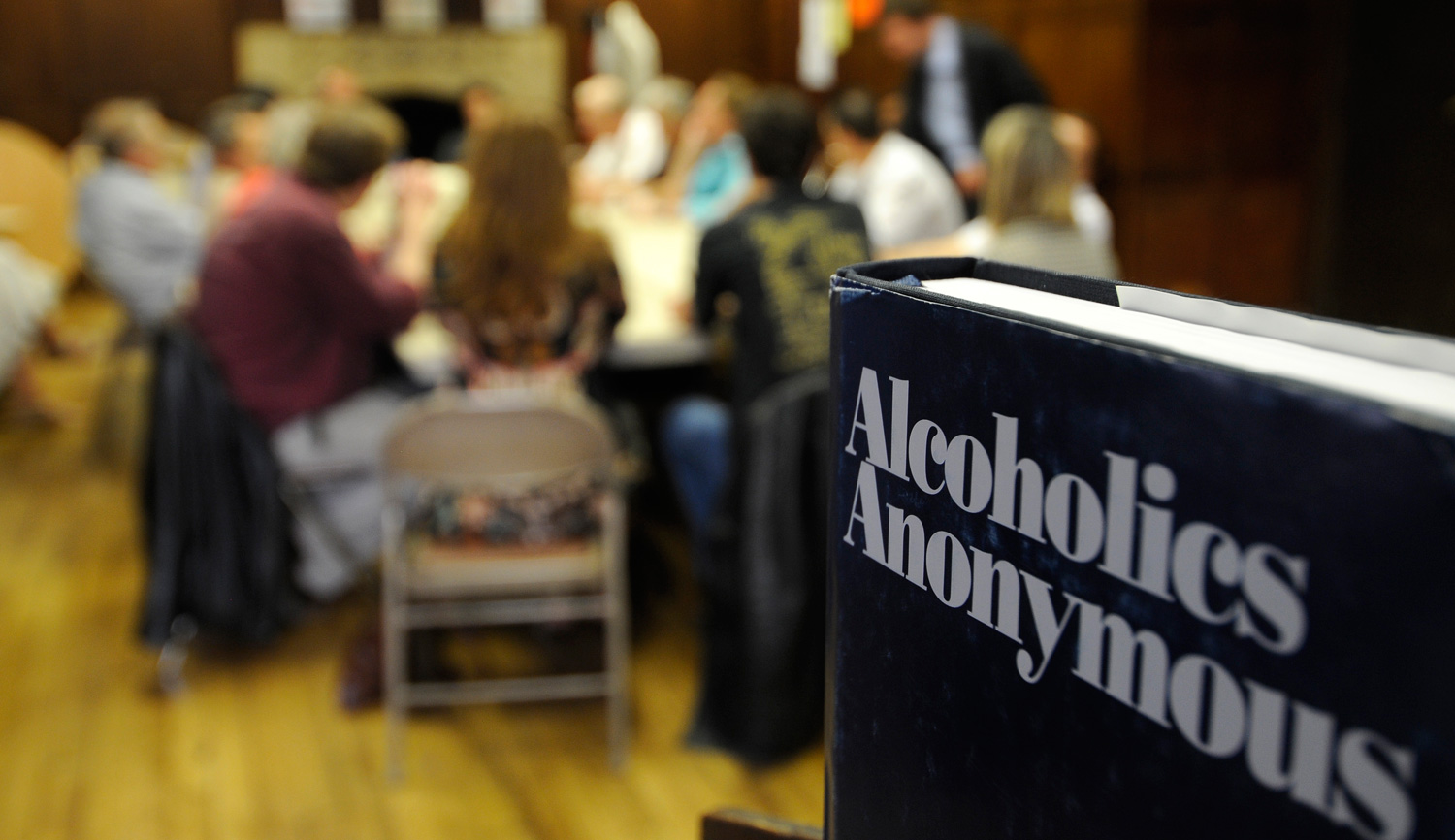

Jeffrey Bloom, in “God, Religion, and America’s Addiction Crisis,” defends a religious approach to treating drug and other addicts, in particular the approach used in “twelve-step” programs patterned on the group Alcoholics Anonymous. Such programs have become a matter of considerable practical importance.

Due to the spread of prescription opioids and, in their wake, heroin, the country faces a wave of drug addiction deadlier than any in its history. Bloom worries about this, and about the addictive potential built (sometimes intentionally) into our computers and smartphones. To judge from anecdotes, as one must with an anonymous group, AA is effective at getting drunks sober. It has thus become a template for fighting other addictions, from narcotics to gambling. Authorities have used mandatory twelve-step visits as a tool of public policy.

At the same time, atheism has come into intellectual and political vogue, and with it a radical understanding of the separation of church and state. Critics want secular substitutes for programs like AA. Bloom would think they are unlikely to find them: getting right with God is the essence of recovery. Bloom’s argument is never dogmatic or prescriptive, and is the stronger for that (although he does beat around the bush in making it).

AA-type programs have religion at their core. They descend from the “Oxford Group” Protestant fellowship of a century ago. The twelve steps followed by attendees begin with “an acknowledgment that we were powerless over alcohol” (or another addictive drug or behavior), pass through “a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him,” and—if all goes well—anchor the recovering addict in a program of moral inventory, atonement, prayer, and proselytism to other addicts. While doctrinal in its origins, AA can be casual and colloquial in practice. People talk more about “sharing” than about confessing.

In hospital rehabilitation centers and court-ordered diversion programs, however, this religious approach is often paired with a “disease theory” of alcoholism that describes addiction as a chronic— even a congenital—brain malady. To rationalist and Promethean thinkers, the consequent mix of chemical arguments with calls to prayer is infuriating—like prescribing the royal touch for scrofula. “Old school” AA members aren’t happy with it, either. They see the “science” of addiction as off-the-point, and as its own kind of quackery. They are sometimes right.

Bloom makes Stanton Peele, author of The Diseasing of America (1989), a stand-in for the anti-AA viewpoint. Peele holds that, in a scientific age, twelve-step thinking can be not only indifferent but outright hostile to reason. Bloom cites repeatedly a complaint of Peele’s: “Is there any more denigrating statement in the addiction field than: ‘Your own best thinking got you here’?”

Bloom sells Peele short. You would never know from Bloom’s account that AA is the complacent “establishment” here, and Peele the ostracized maverick. Peele is right that AA-influenced addiction counselors, and twelve-step groups themselves, often treat reason as worthless. They assume, too, that the experience of the addict carries universalizable lessons. “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results,” they chide addicts who hope to indulge in moderation or keep visiting their old haunts. The counselors often attribute this bon mot to Albert Einstein. (It comes from a 1980s Narcotics Anonymous pamphlet.)

The saying will strike most non-addicts as nonsense, and rightly so. For non-addicts, doing the same thing again and again is not insanity. It is “persistence” or “consistency” or “self-confidence.” Besides, at the end of the day, even the recovering addict expects to remain sober through certain repeated observances, and will be told at his AA meetings, “Keep coming back! It works!”—no matter how long it takes.

Peele, then, is not wrong. What he fails to see is that the emergency of addiction brings about a transvaluation of all values. The tools of reason, science, and common sense are therefore not always accessible to the addict, and may harm him when they are.

Physiologically, addiction boils down to two concepts: tolerance and withdrawal. Thus, Webster’s Medical Dictionary defines addiction as a “compulsive need for and use of a habit-forming substance (such as heroin, nicotine, or alcohol) characterized by tolerance and by well-defined physiological symptoms upon withdrawal.” Such definitions can be expanded and refined to address questions like whether you can be addicted to behavior as well as to substances. They have lately been bent to the demands of political correctness.

The important thing is this: withdrawal is for most addicts a daily trial. The addict’s body sends him messages that terrible things will happen if he does not take his drug. These messages are persistent, painful, and normal-seeming, messages like the ones that tell a non-addict to eat when hungry, drink (water) when thirsty, or sleep when tired. Nor are they necessarily misrepresentations. They can be truths. Alcoholics frequently die of not drinking when they go into delirium tremens. Heroin addicts face a mortal danger when they are cut off from heroin for a while, because they return to it with a dramatically reduced tolerance.

One’s perspective flips. Every addict falling back into his habit, whether it is an alcoholic taking his first drink in months or a gambler rattling the bones in his palm once again, has a feeling of reconnection, reconciliation, and rightness: a sense of being reunited with the “real me.” The sharper your perception and the more vivid your insight, the greater will be the hold of these moments on you. If addiction worked only through your vices, any moralistic fool could overcome it. The addict discovers the vanity not just of human ambition but of human virtue. The expression “Damned if you do, damned if you don’t” is something he lives as an almost literal truth. The solution must come from outside him. In context, this is not “magical thinking” but a form of common sense suited to the addict’s actual predicament.

This is where Bloom’s discussion is especially sensitive and astute. It centers on a correspondence that Bill Wilson, the founder of AA, carried on with the psychiatrist and philosopher Carl Jung in 1961. “Once in a while,” Jung wrote, “addicts have had what are called vital spiritual experiences . . . in the nature of huge emotional displacements and rearrangements.” A wealthy alcoholic had traveled to Switzerland to seek Jung’s help with his addiction. Jung later admitted that AA had provided the drunk with such a “vital spiritual experience” where he himself had failed.

It was natural that the early AA-ers (then considered a fringe group of drunks) should clutch at an endorsement from a lion of the psychiatric profession (then riding high). But Jung’s understanding of what was going on in AA meetings is crude. His spiritualism sounds more Bergsonian or Bacchanalian than religious—indeed, it is the way a drunk might understand sobriety.

The very best part of Bloom’s essay is to show that Jung’s archetypal/anthropological view of the matter, however limited, opens the door to a more classic theological one. Citing Psalm 42, Jung, a pastor’s son, writes of his patient: “His craving for alcohol was the equivalent on a low level of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God.”

This is a pregnant passage! If our modern chatter about wholeness is “equivalent” to medieval reasoning about God, then perhaps God is not dead so much as misnamed. On the other hand, perhaps AA’s God-as-we-understood-Him is not a traditional Creator and Redeemer but a placeholder term for talking about the metaphysics of daily life.

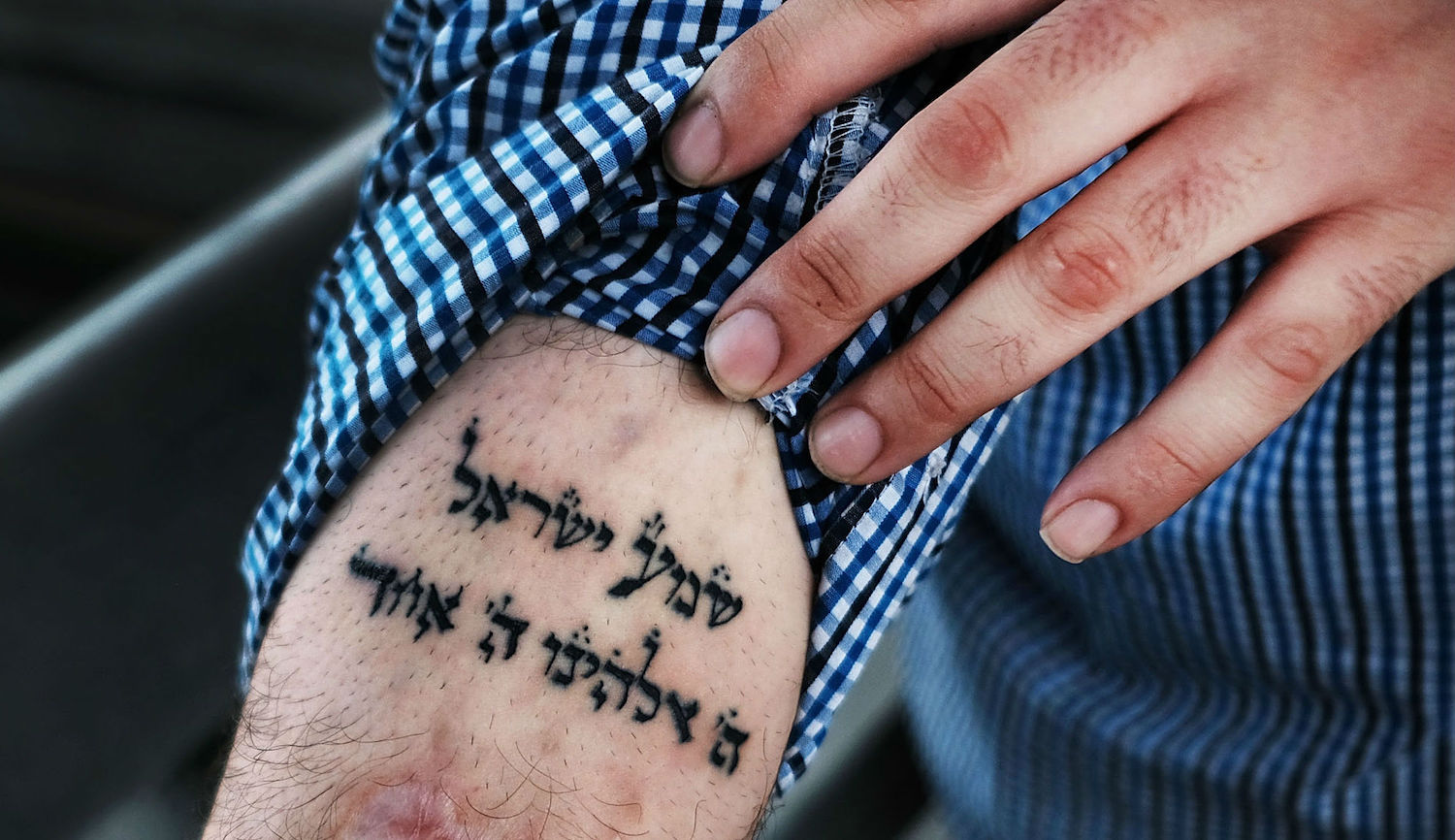

The weakness of Jung’s view is its seeming insistence on an emotional upheaval in one’s relationship to God. These “vital spiritual experiences” are made to sound like the spiritual equivalent of electroshock. The actual twelve-step process, Bloom shows, is different. The “awakenings” found there can indeed be emotional, but more often they involve what William James called spiritual education (as Bloom notes), or what St. Ignatius of Loyola called spiritual exercises. The realization of powerlessness is the “vital spiritual experience.” Once that realization is internalized, the sufferer is open to God and, as Bloom puts it, “available for redemption,” as the Israelites signaled they were at the first Passover. This is a beautiful metaphor, even if Bloom’s describing the exodus from Egypt as “the first recovery narrative” is pushing it.

In an appropriately tentative vein, Jeffrey Bloom approaches the question of how we might make sense of addiction if we used the tools of religion, and specifically Judaism, rather than those of psychiatry. He argues that Judaism binds God and community (or, as he puts it elsewhere, “belief and action”) in a way that makes them hard to disentangle.

The relationship between Jews as a people and Judaism as a religion has provoked fascination, and suspicion, for as long as there have been Jews. Alcoholics Anonymous illustrates in a (relatively) secular way that the border between a “people” and its “belief” can be difficult to draw in any case. Certain beliefs or dispositions can be inseparable from the community in which they are lived.

Addiction places the addict in a terrible epistemological predicament. Only non-addicts can alert him to the non-addicted world that is his real home, yet those “straights” are ignorant of, and unwilling to be educated in, the things the addict knows: the pleasures, the insights, the ineffable satisfactions, and even the invested sacrifices through which a chemical has enslaved him. The point is vital: many of those who would summon the addict back to sobriety do not know what they are talking about. Since their belief does not come with authority, their authority does not provoke belief. They are self-discrediting. Salvation can come only through initiates.

There is a truism that “no one chooses to be an addict.” The statement can be debated, but what is certain is that addiction, when it arrives, imparts a sentiment of inescapability to every day of the addict’s life. Those who have endured it, when gathered together to help and strengthen one another, become a community not just of fate but of destiny.

More about: Addiction, Arts & Culture, History & Ideas