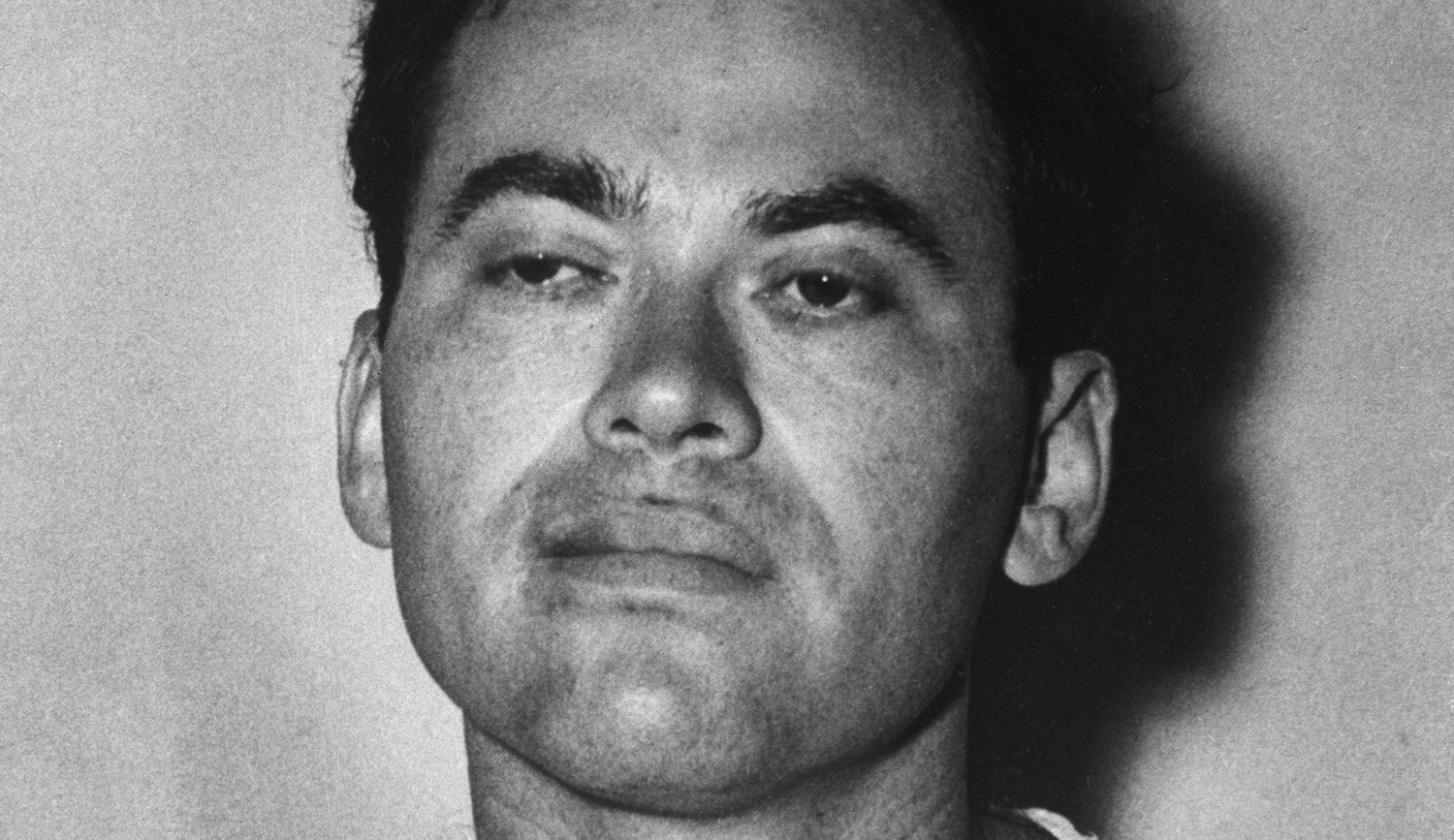

David Evanier’s portrait of Morton Sobell, the last survivor of the American Communist cold-war spies, who died late last year at the age of one-hundred-one, is a devastating and depressing reminder of the political blindness and moral vacuity that long held in thrall a small but significant portion of the American Jewish community. Sobell may well have been more obtuse about the Soviet Union, and personally more manipulative, than most of his fellow Communists, but his brand of fanaticism was unfortunately shared by others.

How many others? It’s important to be clear about this. Although Jews made up a disproportionate share of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA)—perhaps as much as 40 percent in 1939—the party itself never held more than 100,000 members. So, in an American Jewish population of several million, a tiny percentage were Communists. Of course, this is not to count the many sympathizers and “fellow travelers,” drawn by the Soviet Union’s war against Nazism and its seeming opposition to anti-Semitism.

But there was also among Jews a greater number of fierce enemies of Communism than is sometimes credited. In the socialist garment unions, the Zionist enclaves, and the religious world, Jews who understood that Communism was a pernicious doctrine waged a continuous war against its influence. Indeed, for most of the Jewish community, the highly visible presence of so many Jews in the CPUSA, amplified by the location of so many of them in New York, the cultural and intellectual center of American life, was a constant source of tension and embarrassment.

American anti-Semites had routinely insisted that the 1917 Bolshevik revolution was led by Jews as part of a far-reaching conspiracy against the Christian civilization of the West. Henry Ford linked Jews with Communism in his paper the Dearborn Independent, which also translated and circulated the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. During the 1930s, Father Charles Coughlin excoriated Jews on his widely popular radio show. Charles Lindbergh, one of the leaders of America First, cited American Jews’ hostility to fascism as evidence of their alleged disloyalty to the U.S.

After World War II, the beginning of the cold war created a new and potentially even more fraught situation for American Jews. It was one thing for a number of Jews to have supported the USSR in the 1930s when Communists were temporarily on the same side in the fight against fascism in Spain, or later during World War II when the U.S. and the USSR were military allies. It was another thing when, in the late 1940s, the perception of Jewish support, however statistically insignificant, for an enemy of American democracy became much more disturbing.

A series of high-profile events amplified the concern. In 1945, three of the six people arrested in the Amerasia case, the first espionage case of the cold war, were Jewish. (None was ever successfully prosecuted for spying.) In 1947, six of the Hollywood Ten who on First Amendment grounds refused to answer questions when subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Commission (HUAC) were Jewish. In 1949, five of the eleven top leaders of the CPUSA convicted under the Smith Act of conspiring to teach and advocate the overthrow of the American government were Jewish. In the 1948 presidential election, Henry Wallace, formerly FDR’s vice-president now running on the Progressive ticket with Communist backing, drew only a little more than a million votes altogether; but, by one estimate, about a third of American Jewish voters, a much larger percentage than the number of Jews in the CPUSA, cast their ballots for him. (Some unknown proportion may have been attracted as much by Wallace’s support for Zionism as by his left-wing views.)

In 1948, the testimony of Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers before HUAC ratcheted up fears of Soviet espionage in America—and, correlatively, the worry that Jews would be tarred as Communist sympathizers.

One exchange in particular was telling. John Rankin, a racist and anti-Semitic congressman from Mississippi, defended Lauchlin Currie, a White House aide, against Bentley’s charge that Currie was a Communist agent. In her testimony Bentley had cited two other agents to whom Currie had allegedly provided information. Rankin certainly had no sympathy for Communist spies, and little if any fastidiousness when it came to hearsay testimony; what disturbed him was that Bentley had taken the word of two Communists, both with obvious Jewish names, “about what this Scotchman in the White House” had done. (Currie was actually an immigrant from Nova Scotia.) For Rankin, that Jews were likely Communists went without saying; not so a Scot—although Currie in fact had been a Soviet agent.

On another occasion, Rankin gave his colleagues a history lesson, pointing out that “Communism is older than Christianity. It hounded and persecuted the Savior during his earthly ministry, inspired his crucifixion, derided him in his dying agony, and then gambled for his garments at the foot of the cross.” This reflexive equation of Communism with Jews and Jewishness could only have been reinforced by the fact that many others named by Bentley were Jewish with obvious Jewish names—not only (in Currie’s case) Silvermaster and Silverman but also Perlo, Gold, Abt, Halperin, Rosenberg, Glasser.

Fortuitously, the most prominent defendant in ensuing trials was Alger Hiss, a quintessential WASP, while former Undersecretary of the Treasury Harry Dexter White, the most prominent Jewish figure accused of working for the Soviet Union, was not widely identified as a Jew. (After testifying, he died of a heart attack before being charged with any crime.) As for Joseph McCarthy, the Senate’s demagogic scourge of Communism and Communists, he largely eschewed attacks on Jews, the most notable exception being the Fort Monmouth hearings conducted by his Senate committee in 1953.

But none of this succeeded in dispelling the anti-Jewish stereotype, which would only be strengthened following the unexpected Soviet testing of an atomic bomb in 1949 and revelations that the device had been produced through espionage. Although Klaus Fuchs, the German-born British spy at Los Alamos, was the son of a Lutheran minister, he was often thought to be Jewish. His courier, Harry Gold, was certainly Jewish, and so of course were Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, their co-defendant Morton Sobell, David and Ruth Greenglass, and their good friend William Perl (convicted of perjury).

The Rosenbergs cynically exploited their Jewish backgrounds, claiming they were being persecuted solely on grounds of their ethnicity. Their supporters waxed hysterical about a pogrom directed against an inoffensive and ordinary Jewish couple. The CPUSA condemned their trial as a “brutal act of fascist violence.” American Communists in general, including Jews among them, insisted that the case was a prima-facie example of anti-Semitism—even as, in virtually the same breath, they would deny that any anti-Semitic taint whatsoever could be ascribed to the Moscow-ordered execution in Czechoslovakia of eleven leading Communists, including the party leader Rudolf Slansky, and the imprisonment of three others (eleven of the fourteen were Jewish) on the fabricated charge of participating in a Trotskyite-Titoite-Zionist conspiracy. They would say the same about transparently anti-Semitic Soviet denunciations of perfidious “rootless cosmopolitans,” and about the 1953 arrests of Jewish doctors on charges of poisoning Soviet officials.

By the time of Morton Sobell’s early release from prison in 1969, the CPUSA was in tatters, down to a handful of members. Indeed, as newly released FBI files indicate, by the mid-1960s nearly 10 percent of the CPUSA’s 4,500 members were U.S. government informants. In 1971, eleven members of the party’s National Committee were reporting to the FBI, including Morris Childs, who, spurred by Soviet anti-Semitism, had begun working for the Bureau in the early 1950s. Even such stalwart Jewish Communists as Morris Schappes, editor of Jewish Currents, and Paul Novick, editor of Morgen Freiheit and a charter member of the CPUSA, had been expelled or would quit by the 1970s over their support for Israel and/or criticism of Soviet anti-Semitism.

Throughout all of this and for a long time afterward, Sobell himself remained loyal. In his 1974 memoir On Doing Time, published five years after his release from prison, he admitted that the 1939 Nazi-Soviet pact had given him some qualms, but professed his enduring faith in the Soviet Union and his repugnance for American capitalism. Well after having been befriended by David Evanier in the 1980s, he evinced no interest in or concern for Jews either in the United States or in the Soviet Union, or in Israel. As Evanier’s essay makes clear, his commitment to Communism was not fueled by any kind of idealism or moral code—and yet, despite being prodded by the younger man, he used every trick he had to avoid any semblance of a confession. Several years before his death, the most he would say to Evanier was: “I bet on the wrong horse.”

By the early 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening of cold-war archives, even the last illusion held by the dwindling band of faithful Communists and their enablers—namely, that some new piece of evidence would definitively pinpoint the anti-Semitism lying behind the manifestly unjust conviction of the Rosenbergs and their co-conspirators—vanished.

Around this time I attended a conference marking the public release of the Venona documents: decrypted Soviet cables that confirmed Julius Rosenberg’s role as director of a ring of spies. Seated in front of me, Sobell dramatically got to his feet and pulled up the leg of his pants to demonstrate that, contrary to the suggestion by analysts of one cable, he could not have been the nameless spy identified only by the fact that he wore a prosthetic device (an initial, erroneous speculation subsequently retracted, but Sobell ignored that). Sitting next to him, Victor Navasky, publisher of the Nation, long a diehard publication upholding the innocence of one or both of the Rosenbergs, chuckled in appreciation.

Neither Sobell nor Navasky would have much to say after Alexander Feklisov, a former KGB officer who while posted in the U.S. in the 1940s had coordinated the Rosenberg ring for Moscow, named Sobell as a spy, or after the Vassiliev Notebooks (named for the researcher who intensively examined KGB archives in the mid-1990s), provided his code-name: Senya.

Finally, in 2008, Sobell himself would admit that, for more than 50 years, he had lied to his family, his friends, and his supporters. In squandering his life, Morton Sobell, to a significantly greater degree than other Jews who had become Communists or Communist sympathizers, betrayed at once his country and his people.

More about: Communism, History & Ideas, Morton Sobell, Rosenberg Trial, Soviet Union