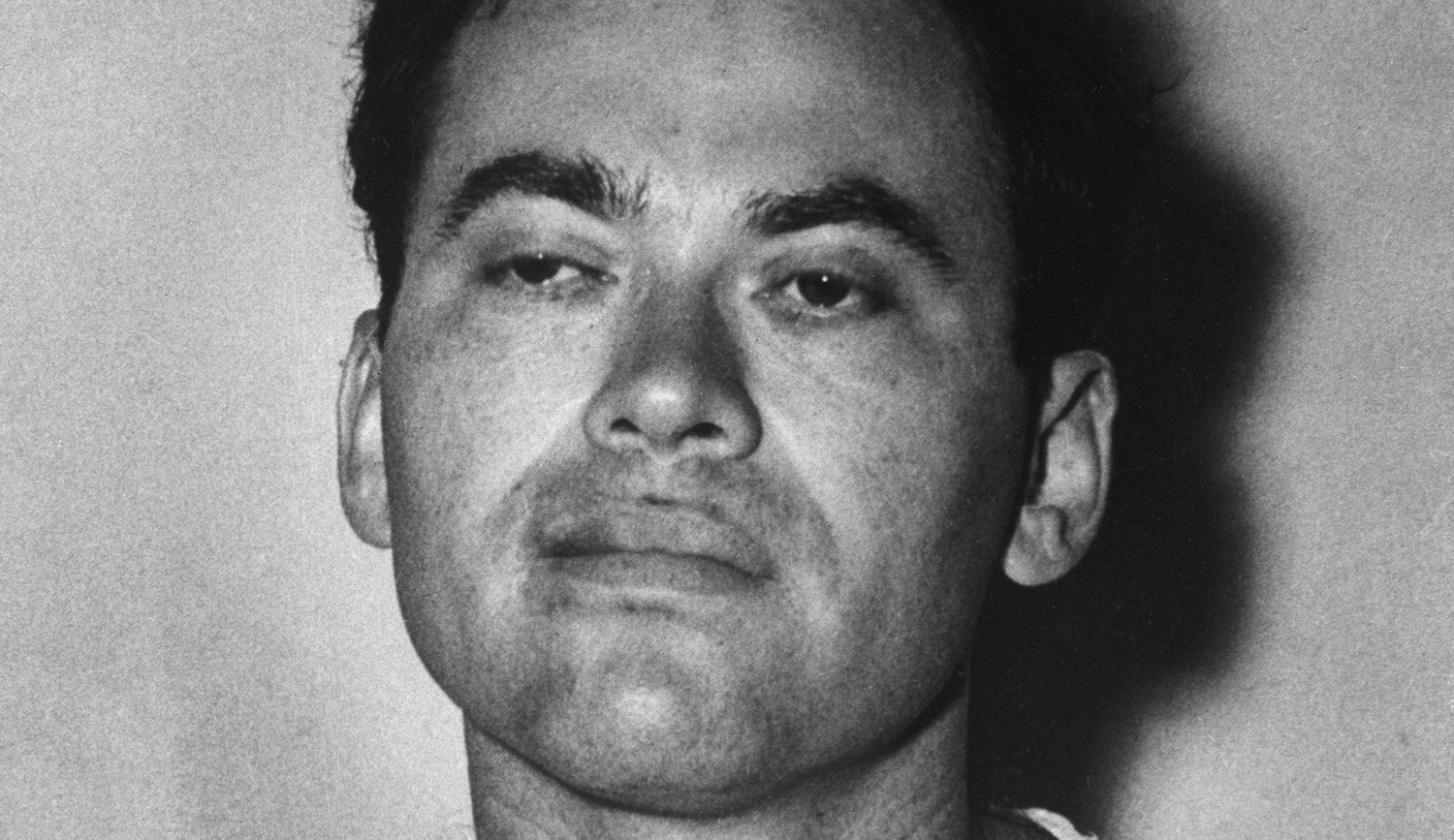

I’m honored that my essay in Mosaic, “The Death of Morton Sobell and the End of the Rosenberg Affair,” attracted responses from Harvey Klehr and Ruth R. Wisse: two pre-eminent scholars whom I hold in the highest esteem. In what follows I hope to enhance and amplify their comments with, where warranted, some personal reminiscences by one who, fascinated by the phenomenon of American Communism from an early age, made it a particular point to befriend Sobell in the early 1980s.

Harvey Klehr sums up the legacy of the convicted spy Morton Sobell in these pithy words: “to a significantly greater degree than other Jews who had become Communists or Communist sympathizers, [he] betrayed at once his country and his people.” In doing so, moreover, Sobell “lied to his family, his friends, and his supporters.” I would add: also to himself.

To be sure, all Communists—and certainly all Communist spies—lied about their intentions; that was to be expected. “Always deny,” Sobell told his girlfriend Juliet. Even in the final active years of American Communism, before the USSR collapsed and Soviet money ran out, Communists still denied they were Communists, and anyone who had the audacity to call them Communists was denounced as a McCarthyite, a fascist, an anti-Semite, a warmonger. Instead, they were “progressives” who wanted only peace, bread, and roses. These last words were those of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Sobell’s co-defendants in the 1951 atomic-bomb spy trial.

But Sobell went well beyond that. He also lied to his son, his grandson, his wives, and his girlfriends. For 58 years, between his release from prison in 1970 and his death last December, he lied to the gullible supporters who had devoted their lives—and a good deal of their savings, not to mention their sanity—to his cause even as he raced around the country and the slave satellites of the Communist world in search of attention and sex with young women, along the way promoting hatred of America, aligning himself with the most extreme terrorist wings of the far left, and keeping alive the myth of the innocence of the Rosenbergs.

All this, from a man who no longer believed in anything. Even Michael Meeropol, the less ideological of the two Rosenberg sons, angrily told Sobell’s second wife that his, Michael’s, life could have been different had Sobell told the truth.

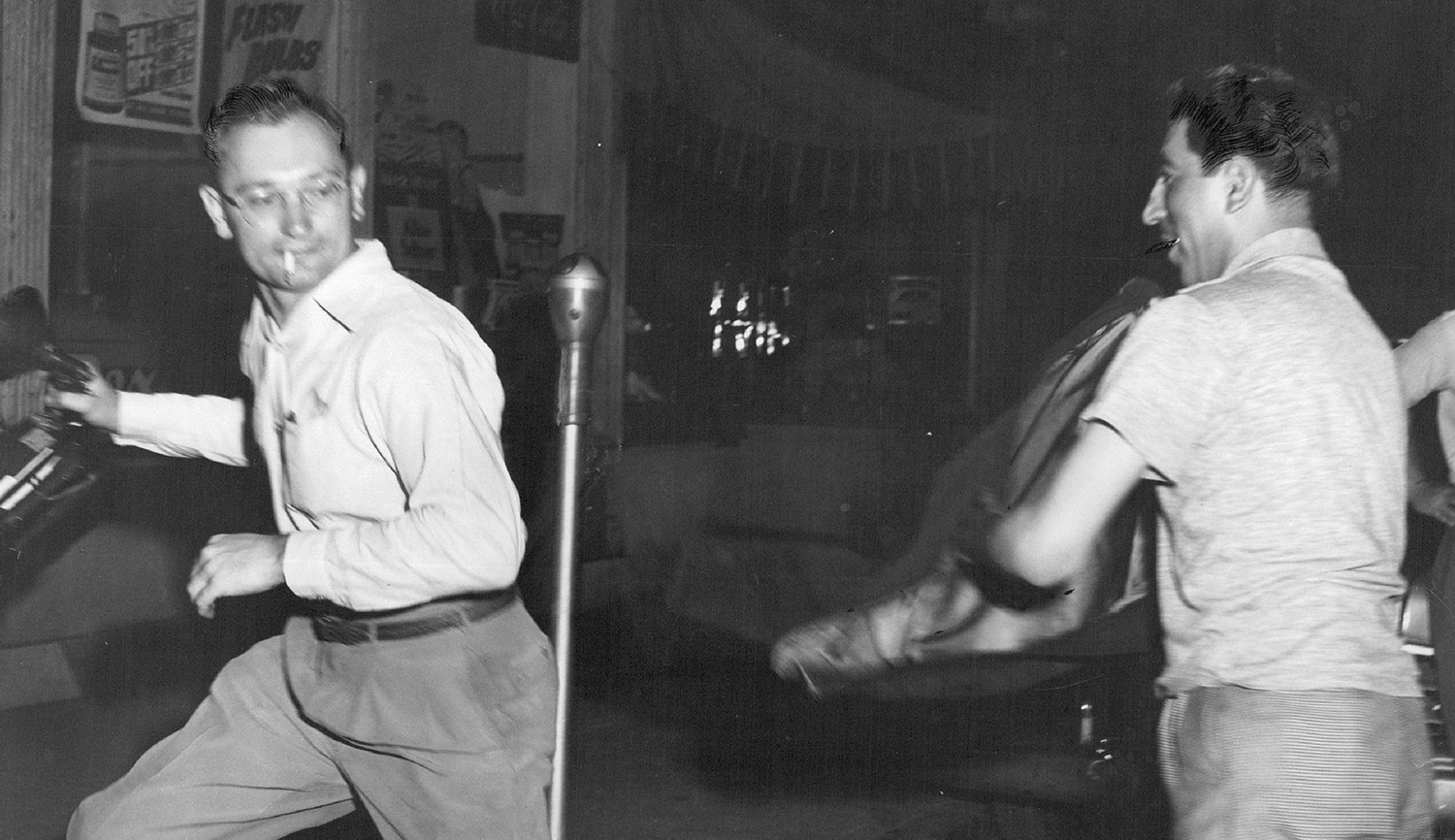

What, then, appealed to me, a young novelist and historian, and made me bombard Sobell in 1982 with phone calls and letters asking him to meet with me? Looking back, I’d point to three personal traits, at once extravagant and enigmatic: his insouciance (“[S]o many years have passed. I’m not sure my memories of Julius and Ethel will have the clarity you need,” was his mock-naïve reply to one of my letters); his spontaneous sense of humor (“Whoo! I just want to have fun!”), so different from the manner of the Communist martinets in the party I had known, dull and colorless, grimly smoking their pipes; and his familiar Bronx Jewish accent, slightly more refined than Bernie Sanders’ but with the same cadences and inflections (and the same contempt for America mixed with the same studied lack of interest in Jewish life or survival).

I agree with Klehr that it’s important not to get the wrong impression: there were far fewer American Jewish members of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) or in the ranks of its active sympathizers than one might think from the prominence of Jewish names among some of its more ardent promoters and infamous offenders. In fact, the vast majority of the American Jewish community was opposed to the Communist movement and to the Soviet Union. And this was true not only in the Jewish mainstream but arguably also in the more rarefied circles of American Jewish writers and intellectuals.

For every hack like the novelist Michael Gold (Jews Without Money, 1930), still celebrated by leftist critics, the roster of distinguished non-Communist and anti-Communist writers includes such masters as Henry Roth (Call It Sleep), Daniel Fuchs (The Williamsburg Trilogy), Albert Halper (The Gold Watch, My Aunt Daisy, Good-bye, Union Square), and Budd Schulberg (On the Waterfront), and, later, Saul Bellow, Cynthia Ozick, David Mamet, Elie Wiesel, Chaim Grade, and Isaac Bashevis Singer.

In the world of ideas, the journal Partisan Review, founded in 1937 by the John Reed Club of the CPUSA, broke with the party over the Stalinist purges, the Soviet betrayal in the Spanish civil war, and the Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact. The magazine, reconstituted in 1939 by its formerly Marxist editors William Phillips and Philip Rahv, became the scourge of Communists and their fellow travelers with its brilliant constellation of writers, including Sidney Hook, Arthur Koestler, Delmore Schwartz, Saul Bellow, Clement Greenberg, George Orwell, and James Farrell.

In his 1982 memoir The Truants, the philosopher William Barrett, who decades earlier had served on Partisan Review’s editorial staff, would write that “in the post-war atmosphere of the late 1940s there had been a remarkable and pervasive resurgence of Stalinism and fellow-traveling that had, subtly or openly, captured the minds of liberals.” Against this, Phillips and Rahv had stood fast: “If any feeling of theirs could claim to be pure and spontaneous, it was this holy hatred of Stalin and Stalinism.”

My own familiarity with Jewish anti-Communists flowered in the mid-to-late 80s when I was compiling interviews for my novel Red Love (1991). The mainstream organizations of the Jewish community included the Anti-Defamation League, which was then in the firm, anti-Communist hands of the formidable Nathan Perlmutter. The American Jewish Committee sponsored Norman Podhoretz’s redoubtable Commentary. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), led by David Dubinsky, was a powerful and vigilant enemy of the Communist-led International Fur and Leather Workers Union. The ILGWU also provided constant financial support to the New Leader, a leading anti-Communist “small magazine” where I worked for a time as an assistant editor.

Scores of Jews who had been enthralled with Communism broke with it decisively in the late 1930s or later and subsequently devoted their energies to combating it. They included Melech Epstein, an editor of the Yiddish Communist newspaper Morgen Freiheit who would later write the important study The Jew and Communism (1959), and John Gates, who resigned as editor of the Daily Worker after Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 speech detailing Stalin’s crimes. Meanwhile, in the world of Yiddish letters, perhaps no one was more passionately anti-Communist than Abe Cahan, the founder and editor of the Jewish Daily Forward.

And then there was Robert Gladnick, who appears in Red Love as “Sammy Kuznekov.” A former district organizer of the Young Communist League, Gladnick idealistically went to fight the fascists in Spain with the Soviet-supported Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Transferred to a Soviet tank unit, he witnessed in Spain the Stalinist regime in miniature, complete with its sadism, terrorism, incompetence, corruption—and anti-Semitism. Upon returning home, Gladnick resolved to fight the Stalinists. He formed the “Anti-Totalitarian Veterans of the International Brigade,” enduring threats from the knife-wielding thugs of the furriers union and expulsion from the CPUSA’s Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

Gladnick was given sanctuary at the ILGWU, where he worked for many years. By the time I met him, he was retired and living with his wife in Florida. At our meeting, he was wearing a bracelet bearing the name of a Soviet Jewish political prisoner. Behind him on the wall of his apartment perched a small American flag. He expressed the hope of being allowed by the Israeli army to serve as a replacement for a young soldier for a month in the summertime. In the United States and Israel, he had found two countries that merited, and repaid, his love and loyalty.

As Ruth Wisse demonstrates in her profound comments, the self-emasculation of Jewish Communists extended not only to the eradication of their Jewish identity but also to their embrace of every cause except their own. Not only did those substitute causes fail to include Jewish concerns, or even Jewish survival, among their priorities, but they frequently functioned as sworn enemies of the Jews. And, as often as not, Jewish Communists were grateful to be used—just as Jewish progressives today are absurdly relieved when “anti-Semitism” gains a subsidiary spot on some long, politically-correct laundry list of objectionable traits.

As Wisse writes, the anti-Zionism of the left, like every position the American Jewish Communists ever took about anything, was linked directly to whatever was the current policy of the Soviet Union. Indeed, it had often been expressly dictated by the Kremlin, as when, along with Moscow, the Morgen Freiheit, enthusiastically supported the 1929 Arab pogroms against the Jews in Palestine.

In this connection, I’m moved by Ruth Wisse’s original and perceptive observations about the Communists’ use of Yiddish, the Jewish language, as an instrument for eliminating both Judaism and Jewish life. In my youth, the non- or anti-Communist Yiddish-speaking world was represented by, as I’ve mentioned, Abe Cahan’s Jewish Daily Forward and also by institutions like the Workmen’s Circle, two pillars of the anti-Communist wing of the social-democratic movement at large and specifically of, in Wisse’s words, those “Jews on the left” who “along with Zionists and traditionalists mounted a stiff resistance to Communism in Yiddish (and in English).”

Today, not only is Yiddish once again utilized by a segment of the Jewish left, but even the Workmen’s Circle, like much of what was once the anti-Stalinist left, appears to have been subsumed by the progressives, to the extent that the organization now sponsors Jewish Currents, once a Communist-party organ. Its editor, Morris U. Schappes, left the party but, like many former true believers, never strayed far from its orbit, and neither did the magazine.

For myself, even after I’d broken free of my teenage “flirtations with the Stalinist swamp” (as I put it in my Mosaic essay), my experience of the party’s mendacity about its subservience to Moscow remained tempered by my fascination with just how saintly, virtuous, and self-righteous many Jewish Communists felt about this obeisance to foreign dictation. Since I’d arrived so late on the scene, my research extended into the past, and included an examination of party behavior during the 1939-1941 Hitler-Stalin pact—which, if anything, should have opened even eyes bedazzled by Stalinist propaganda. But there, big as life, were the party-ordered “pacifist” pamphlets, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” and another pamphlet by Flynn depicting Stalin as “The New Moses of the Jews.”

As Wisse observes, the language of Communism, unlike the barbarous language of Nazism, was the honeyed voice of brotherhood, equality, and social justice. It was Stalin, after all, who had coined the phrase, “Progressive Humanity.” As for the party, it capitulated to Moscow’s pact with Hitler as thoroughly as it had already surrendered its sanity to Stalin himself, and it would always be ready to surrender it again if ordered to do so.

Of course today’s conditions are different, but the temptations on the left to conform to the herd, to belong, to be “soulful and caring” are all in play. And, once again, Jews are being asked to dissolve themselves for the sake of a wider mankind and the “oppressed” by renouncing a “selfish” concern for Israel and Jewish survival.

As if caught in a time warp by such rhetoric, I can’t help recalling Sarah Plotnick, a feisty woman in her eighties with a thick East European accent whom I met while researching Red Love. A former true believer who had considered Stalin “as right as steam heat,” she told me how she would sleep four hours a night in a comrade’s living room, rising at dawn to join picket lines before going to her job as a counter girl at the Automat. After Khrushchev’s 1956 speech, she claimed, she never slept again. But she did manage to locate other outlets for her leftist passions, having recently joined the Black Panthers.

We got along fine until I mentioned Israel. “Why is everybody so hot for Israel?” she shouted. “Goddamnit, what is it? What makes Israel so holy? I’ll tell you the truth: the formation of Israel didn’t juice me up. The Israelis are worse than Hitler.”

So it is surreal to hear the same slogans and language I heard from Sarah Plotnick in the 1980s, language that was itself echoing Jewish Communists in prior decades, being spoken today by young, earnest members of the Jewish left. It’s all there: the fervent anti-Zionism, the “selfless” universalist pose for social justice, peace, freedom, and brotherhood against the selfish parochialism of Jewish survival, the eternal yearning for a socialist utopia in place of the hated America even as that utopia recedes into the distance along with such past models of perfection as the Soviet Union, the People’s Republics of Eastern Europe, Nicaragua, Cuba, Venezuela, North Korea, Communist China, and Jonestown.

Wisse writes powerfully of “Communism’s grounding in lies and in its Orwellian inversion of evil for good.” When I was undergoing my Orwellian experience around the party in the late 1950s, one of the most celebrated poets of the time, Bertolt Brecht, a hard-core Stalinist, brazenly undertook to confront the accusations being lodged against Communism by intellectuals and the mainstream media alike and neatly turn them back against the accusers.

The setting was the final semester of the CPUSA’s Jefferson School for Social Science, a large building on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, one component of the party’s far-flung real estate. In these years after Khrushchev’s speech, the school was breathing its last. Facing the classroom was Herbert Aptheker, the party’s Jewish intellectual, editor of Jewish Affairs, who had written serious studies of black revolts in the South before descending into a raging defender of the Soviet Union. The last of the red-hots, he had published a book attacking the 1956 Hungarian Revolution as a fascist plot. With blazing red hair and wild red eyes, he spoke of the decadent West as “garbage,” “a nest of vermin,” “scum,” “human animals,” “lice,” “bedbugs,” and “trash with the minds of goats and gorillas.”

A portrait of Stalin, years after the monstrous dictator’s death, faced the class, and on the blackboard in front of us was the Brecht poem, assuring us that everything we were being told by the American press about the USSR was false and everything that the USSR said about America was true. Here is the poem:

In Praise of Communism

It is reasonable. You can grasp it. It’s simple.

You’re no exploiter, so you’ll understand.

It is good for you. Look into it.

Stupid men call it stupid, and the dirty call it dirty.

It is against dirt and against stupidity.

The exploiters call it a crime.

But we know:

It is the end of all crime.

It is not madness but

The end of madness.

It is not chaos,

But order.

It is the simple thing

That’s hard to do.(Translated by Jack Mitchell)

No more perfect exemplar could be found of the total inversion of which Ruth Wisse speaks. Today, still among us are those who experienced Soviet Communism personally and saw their lives destroyed, not to speak of those who still live near Communism’s heirs and perpetuators and who, like the people of Hong Kong, are under threat of Communist domination, who risk their lives to oppose its advance, and who understand all too well what it represents.

Sometimes I wonder how my own history brought me to such a different road. Perhaps I was fortunate enough in my life to have witnessed, and been offered, not only real madness but also real and not delusional goodness. The only proper response to such blessings, as the story of Robert Gladnick emphatically shows, is gratitude.

More about: Communism, History & Ideas, Morton Sobell, Rosenberg Trial, Soviet Union