It’s hard to argue with Martin Kramer’s essay on the 60th anniversary of Israel’s capture of Adolf Eichmann. “The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann” shows how his image has morphed from diabolical Nazi to the charming fellow portrayed by Ben Kingsley in the Hollywood film Operation Finale (2018). And in the course of that telling, Kramer explains how clashes of ego among elderly ex-Mossad memoirists furnished Hollywood with the materials it needed to transform our culture’s shared memory of Eichmann. Sadly, he’s probably right that these quarreling former colleagues are not blameless for mischaracterizations of Eichmann.

Kramer’s essay elicits a minor comment about the Mossad, and a substantial one about Eichmann and his most enduring portraitist, Hannah Arendt.

Let me dispatch with the former comment about Israeli intelligence. The earliest memoir of Eichmann’s kidnapping was by Isser Harel, Israel’s mythological spy master. According to recently declassified transcripts of the Security Cabinet, a select group of cabinet ministers repeatedly found time to block publication of his book, even in 1967, when they really had more pressing matters. The ministers earnestly believed that spooks should remain eternally in the shadows. Today’s spies agree, which is why whenever the Law of Archives threatens to force them to open old files, they get an exemption. As Kramer mentions, Harel needed to mount a lengthy legal battle in order to win the right to publish his version of Eichmann’s hijacking.

Indeed, the Eichmann case is altogether exceptional when it comes to the intelligence community’s willingness to clear information that, in other cases, remains confidential. In spite of its assuring everyone that opening even a handful of confidential files will endanger Israel’s security, the Mossad itself eventually put together the public exhibition that Kramer cites, and sent it off on international tour. Make what you will of that.

Ultimately, Kramer’s essay is about America, its taste in historical narrative, and the types of tales Hollywood prefers to tell. A whole response could be written about what Eichmann’s transformation signifies about American proclivities, but it also sent me back to thinking about Eichmann himself, albeit through the prism of Hannah Arendt’s interpretation.

Arendt famously described Eichmann as an illustration of the “banality of evil,” which turned out to be one of the most durable, pervasive, and universally accepted concepts to arise from the Holocaust. She created it while observing Eichmann at his trial in Jerusalem in 1961. It is demonstrably false. But Kramer’s essay has led me to wonder if perhaps that characterization is not quite as false as I used to think.

When, in the winter and spring of 1963, Arendt first presented her view of Eichmann and his trial in the New Yorker, and in the subsequent book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, it defied the consensus view of the Nazis as diabolical fiends. To understand that consensus, consider that even today the Nazis stand in for the worst evil in history. All comparisons to evil are made with reference to them. Right after the Holocaust it was natural to see Hitler and his henchmen as monsters, as despicable, as utterly opposed to all that is good in the civilized world.

Gideon Hausner, Eichmann’s prosecutor in Jerusalem, used to his advantage this popular image of the Nazis as evil incarnate. While, in the trial, he pursued Eichmann’s own deeds during the war—from his career as a young officer in Vienna through his actions as a seasoned commander in Budapest—Hausner also treated Eichmann as a proxy for the top Nazi leaders, now dead, who could no longer be tried. With Eichmann sitting before him, Hausner sought justice from the likes of Heinrich Himmler and Hitler himself.

Survivors were brought to tell their gut-wrenching stories. They divulged the atrocities they had managed to endure. They bore witness to the mass death they managed to escape. And they told about all of the diabolical Nazis who perpetrated the war against the Jews of Europe. Of course Eichmann himself had not personally been present at all of these places, committed all of these crimes, nor even commanded them. Hausner significantly overstated Eichmann’s centrality to the Holocaust.

Recall that, at the time of the trial, there was not yet well-documented academic research into the events. At the time, the European war against the Jews did not even have a name, neither Holocaust nor Shoah. Raul Hilberg’s ground-breaking The Destruction of European Jews was about to be published by an obscure publisher to initial general indifference. Hausner’s portrayal of perfidy and monstrosity was plausible and convincing. He strengthened extant public perceptions of the Nazis.

But Hannah Arendt wasn’t convinced. First, she correctly saw that Eichmann the defendant didn’t have to answer allegations that he invented or oversaw the entire Final Solution. The allegations he did have to respond to were horrendous enough, but in point of fact Eichmann hadn’t been at the top of the system. In addition to considering some of the charges against Eichmann to be spurious, Arendt also assumed that Hausner was not conducting the trial dispassionately. She thought that he was motivated by political concerns, and that perhaps he was even the Israeli prime minister David Ben Gurion’s pawn. She disliked Hausner for that, and I suspect that she had made up her mind on that before she ever arrived in Jerusalem.

Once in the courtroom, however, she was struck by the degree to which Eichmann, the specific man and not the symbol, didn’t seem diabolical at all. On the defendant’s bench (actually a chair in a bulletproof glass case), he didn’t much fit the bill. Eichmann was middle-aged, bespectacled, and balding. He was correct in manner and well-behaved; above all, he was boring. Arendt made much of the discrepancy between the unremarkable man sitting before her and the deranged figure Hausner was presenting. So she spun an alternative tale in which Eichmann had been an unthinking, nonentity caught up by the winds of history who brought about murder on an unprecedented scale without actually having to think about what he was doing. He was banal, not a monster, and that was the unsettling lesson she took from his trial. It was an original portrayal, and it increasingly gained disciples.

Some of those disciples took her idea and extended its implications further even than she had intended, universalizing the example of Eichmann so that any normal person, facing the choices he faced, would likely behave as he behaved. And as Kramer has now shown, this unwarranted generalization about Eichmann has continued over time such that, now, the most powerful portrayals of the man are totally ahistorical and quite implausible. Eichmann, according to the assessment first offered by Arendt, and by now elaborated beyond Arendt, was not only not a monster, nor was he banal, but he was almost charming. Yes, he may have lacked the ability to question his orders, but he is like all of us; if you give him a chance, he could be talked out of his erroneous ways. Be patient with him. Be kind to Eichmann; he’s not so bad, after all.

That entire line of thinking is nonsense.

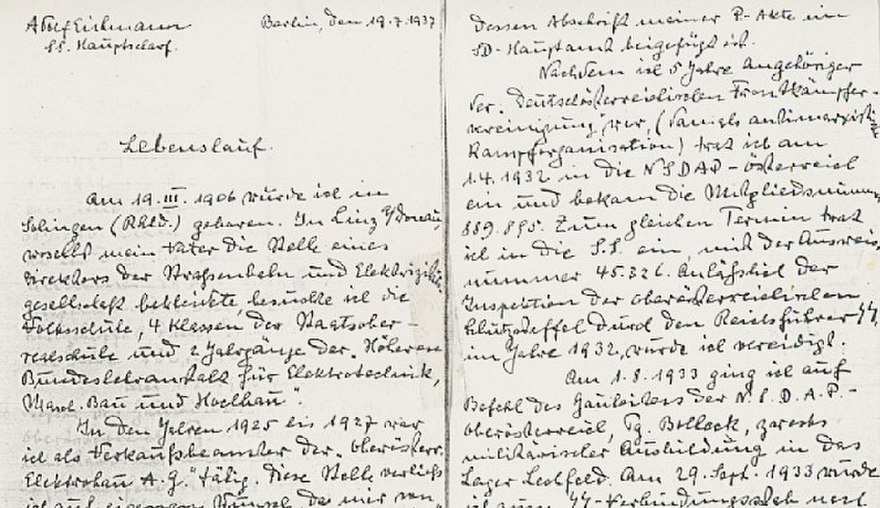

The truth of Eichmann’s character emerges from the thousands of documents he left behind, along with dozens of hours of interviews he recorded in 1957 with the Nazi-leaning journalist Willem Sassen, to which can be added hundreds of hours of recorded interrogations in Israel prior to his trial, and of course, his behavior in the Jerusalem court. All of this material was produced in the native language that Eichmann and Arendt share, German.

Arendt seems to have seen some of the documents, none of the interviews, and probably not more than a fraction of the transcribed interrogations, and she based her defining portrait of the man almost exclusively on his appearance in the courtroom. But the staid Eichmann she saw on trial was far removed from Eichmann at the height of his power. As a result, she minimized his anti-Semitism and his fealty to Nazi ideology, its leaders and, its methods, and downplayed the tremendous emotional energy and bureaucratic creativity he drew from his place in the Nazi hierarchy. On all of these crucial points she was wrong, and the afterlife of her errors disfigures portrayals of Eichmann to this day. He was not a German Everyman. He was, instead, a fervent ideologue and anti-Semite.

But he was something else, too; and Kramer’s essay makes me wonder if it’s time to readjust my own reading of Arendt. She did, in fact, understand an aspect of Eichmann that is not comprehended by his portrayal either as evil incarnate or as an automaton without agency. To understand Eichmann, you have to see how innovative and utterly committed he was as a bureaucrat.

Eichmann was a common type in the Germany of Arendt’s generation: a low-level Beamter who was a tenured official. This type was not stupid, but not particularly well educated or imaginative, either. This type of person grounded his identity in his place in the system, and drew his pride from his participation in its operations. Eichmann does not stand in for all of us, in a “man’s inhumanity to man” sort of way, but rather, for a particular kind of early-20th-century German-speaking bureaucrat that is also familiar from the fiction of Franz Kafka.

Arendt had surely met many such men (they were almost all men) in the Germany of her youth, and had probably disdained them as intellectual inferiors (as they probably were). She did not approve of the way that Eichmann and his ilk used the revolutionary context of Nazism to climb far higher into the heights of society than they could ever have expected, or indeed should have achieved. As she saw it, this unexpected path to professional advancement and higher social standing was the very advantage that inured such men to the muted voice of their conscience.

Captured from hiding in Argentina, interrogated by the Mossad, and then brought into an Israeli court to argue for his life, Eichmann reverted to form and displayed the subservience that had always been an important characteristic of such men. He treated his interrogators and judges as would any other low-ranking Beamter. Let’s allow Arendt the final word:

He was not stupid. It was sheer thoughtlessness—something by no means identical with stupidity—that predisposed him to become one of the greatest criminals of that period. And if this is “banal” and even funny, if with the best will in the world one cannot extract any diabolical or demonic profundity from Eichmann, that is still far from calling it commonplace.