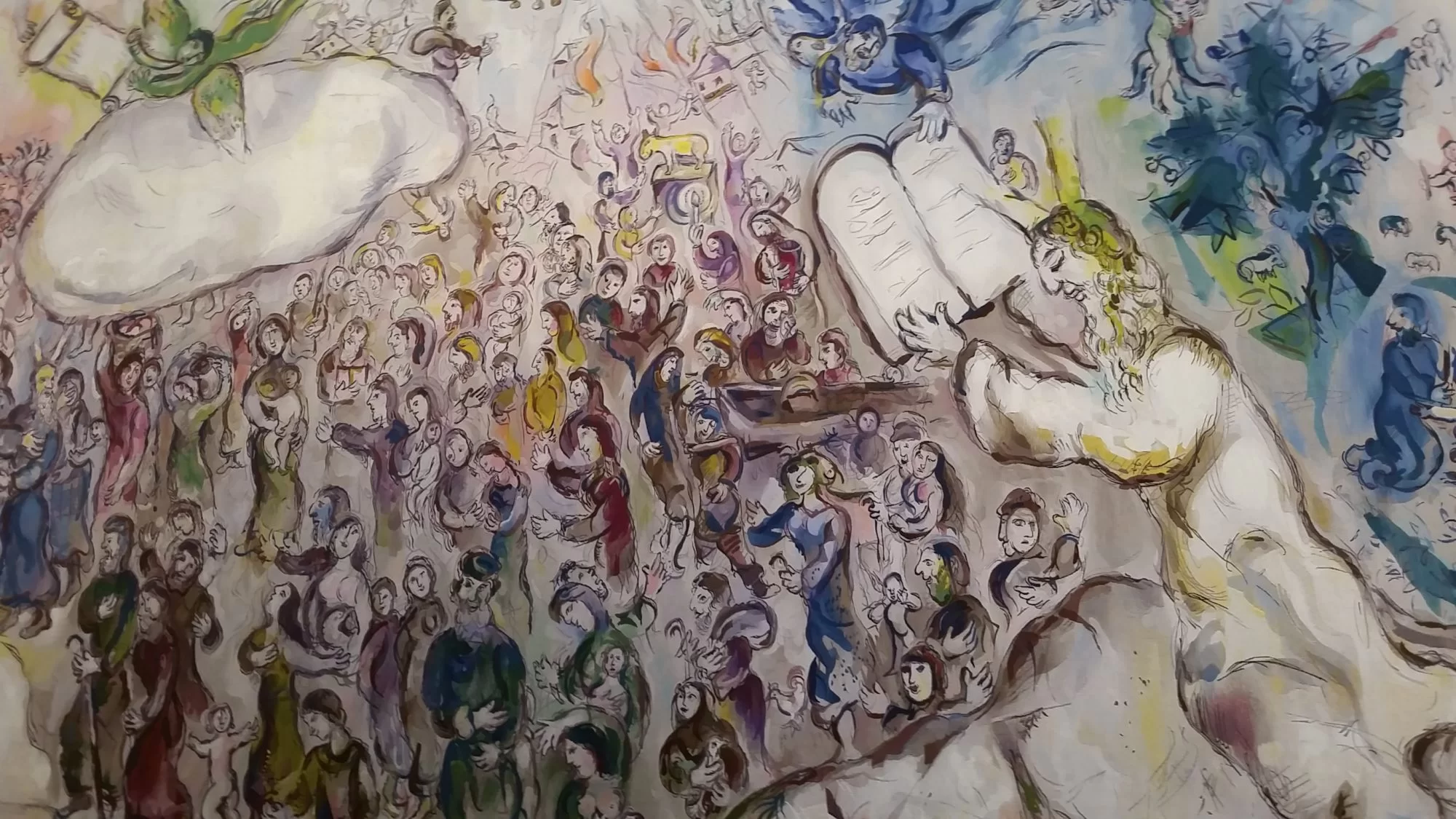

“What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” Thus the famous cry of Tertullian, the ancient Christian theologian, as he blamed Greek philosophy for its corrupting and heretical effects upon early Christian doctrine. Although Tertullian himself was not without his heretical aspects, notably his attraction to the fringe doctrine called Montanism, his words pointed toward a grand tension between reason and revelation, between Greek philosophy and biblical religion, the twin poles that, as Leo Strauss argued, made Western civilization what it is.

Athens stood for the spirit of free rational inquiry undertaken in a largely intelligible world whose contours and dimensions are commensurable with our powers of understanding, and thus will yield answers to our queries. Jerusalem stood for the spirit of piety, which concedes the weakness of human understanding and the inadequacy of unaided human nature, and insists that we are utterly reliant for guidance upon the few ways in which God has revealed Himself and His will to us, and that such reliance constitutes a wisdom superior to any ratiocination, since God’s ways are not ours. In this view it is by our faith that we are saved and not by our knowledge; and, as the apocryphal book of Ben Sira has it, there is “nothing better than the fear of the Lord, . . . nothing sweeter than to take heed unto the commandments of the Lord.”

The antagonism, Strauss argued, between these two “conflicting roots” is “the core, the nerve of Western intellectual history,” and the secret of the West’s vitality—a life lived “between two codes,” in fundamental and unresolved tension. We would no longer be ourselves, he believed, should we become all one or all the other.

A variant version of this antagonism was offered by Matthew Arnold in one of the essays collected in his famous 1869 book Culture and Anarchy, in which Arnold proposed a contrast between “Hellenism” and “Hebraism.” He considered the two to be competing “spiritual disciplines,” each aiming at man’s perfection or salvation. “The uppermost idea with Hellenism,” wrote Arnold, “is to see things as they really are; the uppermost idea with Hebraism is conduct and obedience.” These divergent conceptions were in turn rooted in divergent perceptions, divergent experiences. “As Hellenism speaks of thinking clearly, seeing things in their essence and beauty, as a grand and precious feat for man to achieve, so Hebraism speaks of becoming conscious of sin, of wakening to a sense of sin, as a feat of this kind.” Hellenism celebrates man’s capacity for perfection and glory, in and through the exercise of his own power; Hebraism reminds him of his capacity for ignominy and shamefulness, in and through the same exercise. Neither impulse could ever succeed in driving the other away entirely; each enjoyed its season of dominance, and its season of recession; both had roles as successive elements in an unfolding economy of mind and spirit.

I found myself thinking of these precedents in reading this forcefully argued article by Eric Cohen and Mitchell Rocklin. What they are trying to do is nothing less, it seems to me, than calling the Jews of postmodernity to be a light unto the nations in a whole new way, now taking up the task of saving the West from itself, in much the same way that Joseph saved the very brothers who had sought to murder him. This may seem wildly improbable at first glance, not to mention a very heavy lift; and it certainly is historically ironic, as Cohen and Rocklin say, and as my Joseph comparison implies.

But why should it not be considered entirely in keeping with the long arc of Jewish history, and with the guiding theme of Jewish chosenness? Judaism in its fullest expression has always been a particularism ultimately aimed toward universality, toward the eventual redemption of all humankind, not toward a parochial insularity and self-segregation, as its critics charge. And what better way to defeat the cynicism of today’s cultured despisers than by knowing their foundations better than they do themselves, running rings around their pretensions rather than retreating into a piety and isolationism that tries, futilely, to wall those influences out?

There is the practical question of whether the demand exists for the kind of Jewish classical schools that Hildesheimer and Hirsch created in the 19th century, schools whose sprawling curricula are so breathtakingly demanding that they amount to two or more educations in one. But one cannot know for sure until one tries, and it will not take a large number of such schools to train a small elite group to carry forward the Cohen/Rocklin vision to the next stage of development. It is a grand experiment, and it is well worth trying.

The one place where I found the essay wanting in detail, though, was in thinking through what is meant by “the Jewish meaning of the West.” I have my own reflections about that, which may or may not be useful, and will conclude with them.

First, I think it is useful to return to the Athens/Jerusalem or Hellenism/Hebraism pairings that I have already mentioned. Though both are oversimplifications, they have something important in common. In each case, the latter item of the pair denotes a hard and impassable limit to human understanding or human endeavor. There are things we do not know, and cannot know, and we may be punished severely for trying to know them. The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.

The Hebrew Bible is replete with cautionary tales about man’s propensity for transgression and prideful disobedience. The reasons behind God’s limitations upon us are not always forthcoming, and may defy rational explanation. Why was there a forbidden tree bearing forbidden fruit in Eden? We are never told. “Nor are your ways My ways,” says the Lord, “For as the heavens are higher than the earth,/ So are My ways higher than your ways,/ And My thoughts than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:8-9). But it was the serpent’s pitch to Eve in Genesis 3:5 that she could be as God, if she would only have the courage to disobey Him. She found out.

The relevance of these sturdy Hebraic insights to the present moment is clear. Just as we have much to be proud of in the modern West’s conquest of nature, so we have much to fear from what will come of the transgressions it has made possible. Is there any identifiable limit beyond which the comprehensive and willful re-engineering of human life upon which we are embarked will not go? Are there shadowy places where we should resolve never to explore? Do we have any strong principles that can establish and enforce those limits?

Perhaps we do. Perhaps a recovery of our Hebraic heritage of reverence for the world as the handiwork of a single all-powerful Creator, who spoke the world and all its creatures into being ex nihilo, can accomplish that. The entire West needs the giant stiffening of its spine that would come with a recovery of that fearful wisdom, if it is to have any hope of remaining free. If Cohen and Rocklin’s schools seek to engender that wisdom, along with the immense amount of learning that they will surely require in other areas, then they will be the answer to much of what ails us. And ironically, they also will be an answer to the question with which I began.

More about: Education, History & Ideas