I read “The May 1948 Vote that Made the State of Israel,” Martin Kramer’s fascinating account of the story behind Israel’s declaration of independence, with much pleasure and interest. The essay has much to teach us not only about the annals of the Jewish state in its formative years but also about how history in general gets written (and rewritten).

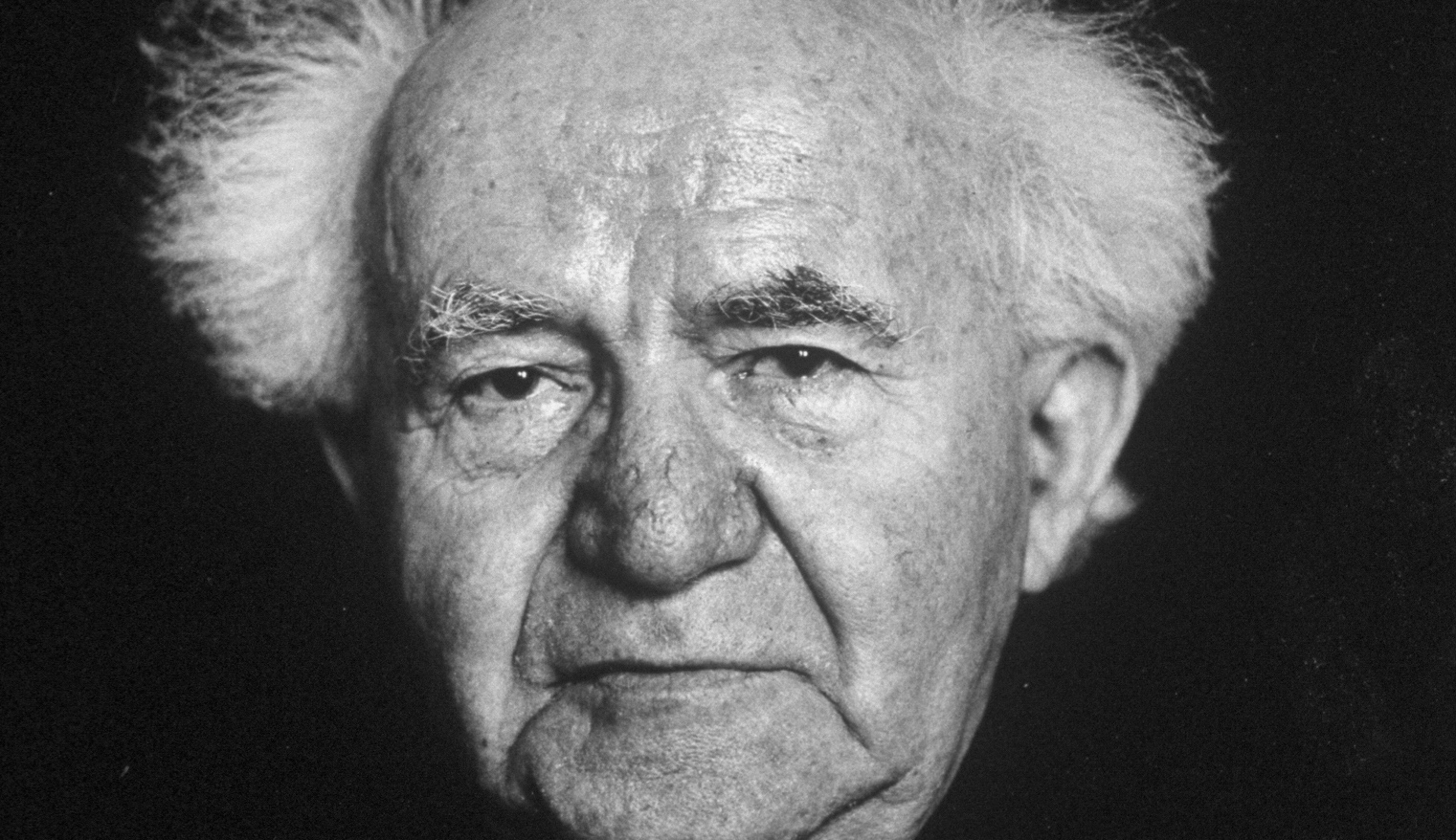

Here I’d like to respond to what emerges as the main topic of Kramer’s essay, namely, David Ben-Gurion’s attitude toward the issue of the Jewish state’s borders, how that attitude was reflected in his handling of the pre-state deliberations over whether or not to specify those borders in the declaration of independence, and the extent to which his position on the issue may or may not have changed over the ensuing decades.

In exploring these matters, Kramer begins with the footage of a 1968 interview with Ben-Gurion that recently aroused much talk in Israel when it was included in the documentary film Ben-Gurion, Epilogue. As the author of the Hebrew book on which the film was based, I have a special interest here.

In that 1968 interview, the then-eighty-two-year-old Ben-Gurion did indeed say that “If I could choose between peace and all the territories that we conquered last year [in the Six-Day War], I would prefer peace.” As Kramer notes, reviewers of David Ben-Gurion, Epilogue and various press commentators immediately pounced on this statement in order to claim Ben-Gurion posthumously for Israel’s left-wing “peace camp”—a claim that Kramer rightly proceeds to demolish by, among other things, retrieving the Ben-Gurion of 1948, whose attitude toward captured territory was decidedly different.

In agreeing with Kramer about Ben-Gurion circa 1948, I would add that even in 1968, not only was his stated choice of peace over territory seriously qualified by his simultaneous insistence (as Kramer notes) on retaining the Golan Heights and all of Jerusalem, but he included Hebron as well. By the early 1970s, moreover, he also favored keeping the settlements that had started to develop in the conquered West Bank, explaining that under conditions of “true peace” there should be no problem of Jews living under Arab rule just as Arab Israelis lived in the Jewish state.

Of course, Ben-Gurion could not have been foreseen the eventual magnitude of the settlement project. Even so, however, it’s hard to associate his position with that of the current Israeli left. If in principle he might have preferred true peace over “all the territories,” in practice he was unwilling to surrender all of them. Even today, Jerusalem, Hebron, and the settlements remain among the most contentious items in Israel-Palestinian negotiations, and the status of Jerusalem in particular is so vexed as to have been repeatedly deferred till a later date.

In refusing to specify the territory of the nascent state or to address the issue of its borders in the declaration of independence, Ben-Gurion wanted “a license,” as Kramer writes, “[to] incorporate any strategically vital territory seized in war with an Arab aggressor.” I would put the point differently, and in a way that to me does greater justice to the complexity and sophistication of his thinking. Ben-Gurion saw the issue of borders as a tool, or a means, toward greater ends, in pursuit of which, basing himself on national needs and interests in any given circumstance, he was willing both to conquer and to cede.

In April 1970, in his last speech as an active member of the Knesset (he died in 1973), Ben-Gurion warned Israel’s political establishment about a dilemma into which, he feared, it was likely to fall:

The Six-Day War created new trends, or what seem to be new ones: [of] lovers or seekers of peace and [lovers of possessing] the whole Land of Israel. I don’t know to which of them I belong. I was for both things all my life. . . . These two things, peace and the whole Land of Israel, as long as they were attainable and possible, I supported them wholeheartedly, . . . and therefore I don’t see any contradiction between these two things. It’s not [an issue of] two parties but [of] two different situations.

Where the territories captured in 1967 were concerned, Ben-Gurion was urging an attitude that was neither ideological, nor fundamentalist, nor theological; it was political. The proper disposition of the territories was a practical question, and any decision about them should rest on realistic assessments. What mattered most was to secure the existence of the state and ensure a Jewish majority. That being the case, it was necessary to define with the maximum possible confidence the nature of the peace that would be acceptable to Israel in exchange for territorial withdrawal.

Three fundamental principles in Ben-Gurion’s general worldview may help explain his position.

The first was his belief in the dynamism of history. Borders, he believed, were meant to be drawn and redrawn over time. In a 1939 speech, he traced one of the weaknesses of mortal beings to their tendency to assume that nothing would ever change, which left them constantly struggling to catch up with historical developments:

The minds of movements, much like those of people, lag behind the course of events. The mind clings to inertia, routine, habits. . . . The mind is always lazy, assuming that what has been will always be. But events are different. The world doesn’t hold still, history doesn’t hold still, nature and human nature don’t hold still. . . . When, at a specific moment in time, a familiar system starts unraveling, the mind still refuses to see it because doing so requires big efforts, finding new paths. And it is hard, because a man has a limited amount of energy and has to invest it in his struggle for survival. And he can’t turn his mind to look at the future changes in history.

The sanctification of specific borders as an ultimate goal was therefore, to Ben-Gurion, a political mistake, a denial of their malleability in response to historical transformations.

The second principle stemmed from his investigations into the real map of the Land of Israel, which in 1918 he published as a book co-authored with Yitsḥak Ben-Zvi: Erets Yisrael ba’avar u-vahoveh (“The Land of Israel, Past and Present”). There Ben-Gurion concluded that neither Jewish scripture nor Jewish history offered an unequivocal definition of the borders of the Land. Instead there were many maps, reflecting various positions and changing ethnographic realities. From this it followed that one must be careful to separate the Jewish people’s historical right to the entire biblical Land of Israel from the political implementation of that right at any given time.

Finally, there was his belief in the movement of world history toward a future in which individual states would unify into clusters operating politically as federations or confederations. In a way, he was in tune with the founders of the European common market and the future EU. (During the 70s, he even sent letters to Latin American leaders suggesting they move in the same direction.)

In 1962, Ben-Gurion summed up his vision in these words:

Western and Eastern Europe will become a federation of autonomous nation states with socialist and democratic governments. . . . [Except for] the USSR, which will remain a [separate] federative state, . . . all the other continents will become federations of autonomous nations united in a global alliance. . . . The UN will build a memorial to the Hebrew prophets in Jerusalem, and next to it will be the hall of a supreme court for the entire human race, which will settle any dispute between the federative continents.

As for Israel’s distant future in particular, he envisaged a federation of Jewish and Arab states in the Middle East—where, as elsewhere in the globalized world, borders would be less significant.

While making allowances for the utopian tone of these passages, one might characterize Ben-Gurion’s attitude toward the question of Israel’s ultimate borders as, in a word, flexible—a pragmatic outlook that neither committed itself to, nor sanctified, any specific political aim or territorial boundary.

With this approach in mind, one can understand both why he refused to specify the country’s borders in the 1948 declaration and was perfectly prepared to occupy more land than had been allotted to the Jewish state in the UN’s 1947 partition plan—and why, as Martin Kramer writes, he forbade the Israel Defense Forces to obtain even more territories in the War of Independence. In his later years, he wanted the next generation of Israeli leadership to think about the territories as one element in a broad strategy meant to secure the continued existence of the Jewish people within its state and, with respect to potential peace agreements, always to weigh opportunities against risks and needs.

More about: History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism