Last month, Wang Qushan, vice-president of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), paid a visit to Israel during which, together with Prime Minister Netanyahu, he attended the fourth session of Israel’s Innovation Summit. Also attending the conference was Jack Ma, founder and CEO of the global conglomerate Alibaba, who has made Israel one of his favorite destinations—which is another indication that Chinese business leaders take Israel seriously despite the obvious discrepancy in the two countries’ size and population. The visit, and the pattern of cooperation established by previous sessions of the China-Israel Joint Committee on Innovation Cooperation, lend weight to Arthur Herman’s description in Mosaic of the fast-growing relationship between these two dramatically unequal but mutually respectful peoples of ancient lineage.

Yet Herman also fears that Israel will be swept into China’s more powerful orbit, and that this may create a gaping hole in the West’s technological defenses against encroaching Chinese ambitions. In this, Herman is not alone among either Israelis or Americans. He quotes, for instance, the stern cautions of Israeli Rear Admiral Shaul Chorev on the future of Haifa harbor, a longstanding port-of-call for the American Sixth Fleet whose operation is now under contract to Chinese corporations. Such cautions are reportedly voiced more angrily by American officials alarmed at the possibilities for Chinese surveillance and information-gathering. The PRC also presents a fierce challenge to both Jerusalem and Washington in the field of cybertechnology (a point Herman mentions but does not elaborate upon), potentially creating severe consequences for their defenses against cyber espionage.

Nevertheless, in my judgment both Herman and Trump administration officials overstate the magnitude of the threat—perhaps because they have neglected to take fully into account the broader scope of Israel’s interests in the Middle East and Asia. Those interests in fact coincide with and reinforce the national interests of the United States.

Beijing’s emerging policy in the region is indeed of great relevance to Israel. When it comes to Israel’s narrow economic concerns, it is easy enough to see why. China offers both a vast domestic market for high-end Israeli goods and a source of investment in the ever-growing Israeli economy. For Israel, a country now fully dependent on its high-end trade, these are not trivial matters.

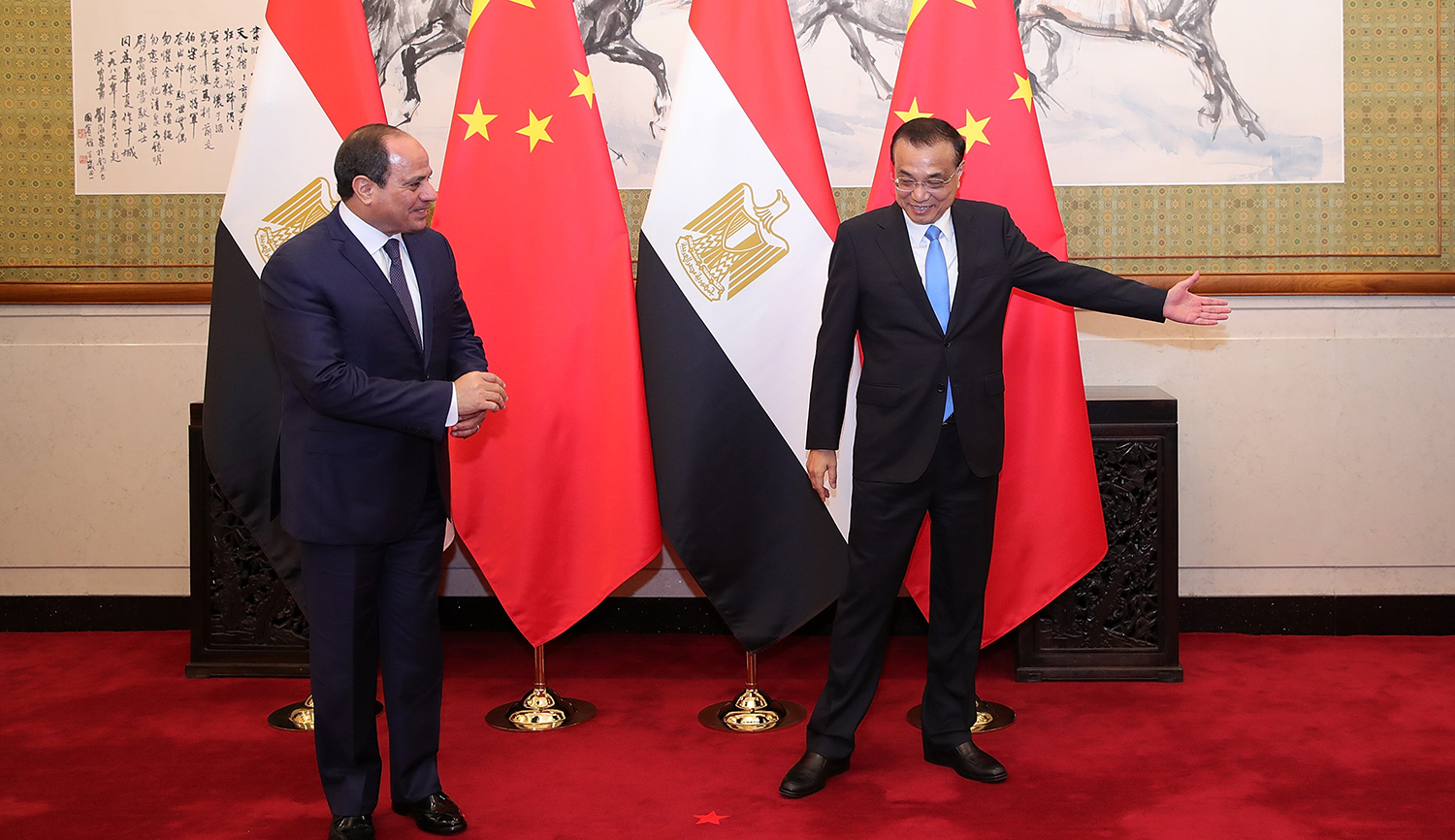

But equally pertinent is the potential role of the PRC as a stabilizing strategic presence in the region. As I have written elsewhere, few things would be as harmful to Israel’s prospects of survival in its rough neighborhood as the collapse of Egypt into dysfunction and chaos; even worse would be an Islamist seizure of power. Fortunately, Egypt’s importance as a node in the One Belt One Road project is recognized in Beijing, and Chinese firms already hold the principal contracts for the new “administrative” capital being built east of Cairo. It is very much in the interest of both Israel and the U.S. that China continue to be a long-term strategic investor in Egypt’s growth and stability. This is not a zero-sum game. It is a geostrategic win-win.

True, China also maintains a warm relationship with Iran, the archenemy of both Israel and the Sunni Arab states. But here, too, Israel’s relationship with China has proved a mitigating factor. Herman cites the analyst Sam Chester on how Israel was able to persuade the Chinese that a failure to curb Iran’s nuclear project would plunge the region into mayhem, with disastrous consequences for China’s regional objectives. Indeed, by invoking a credible threat of military action against a nuclearized Iran, a 2010 delegation (of which I was a member) led by Moshe Yaalon, then Israel’s minister of strategic affairs, helped bring about a surprising Chinese vote in favor of UN Security Council Resolution 1929, imposing far-reaching sanctions on Tehran.

Today, a sober calculation by China of its own interests, backed by the forceful suasion of both Israel and the U.S., might well produce a decision by Beijing that the cost of supporting Iran has become higher than Iran is worth.

That in itself would be a good reason for keeping Israel’s channels to China wide open.

Herman’s depiction of the Chinese challenge also omits the main thrust and most salient aspect of Israel’s security-related efforts in Asia. Those are in fact directed not at China but, quite the opposite, at the range of nations seeking to build a counter-balancing strategic capacity to China’s bid for hegemony. Beijing may indeed be harboring far-reaching designs for the arc of nations that stretches from Japan to India, but others in that arc are not exactly willing to be dominated.

In the struggle to sustain the Asian balance of power, Israel has emerged as a key actor and partner. Within the last few years, Japan has dropped its traditional reservation about security cooperation with Israel, Vietnam and the Philippines have emerged as markets for the products of the Israeli defense sector, coordination with Australia has intensified, and, above all, Israel’s two-decades-old relationship with India in the realm of military hardware has become even more extensive and intimate than ever. All of this is happening while Israel studiously avoids, under the terms of a highly intrusive agreement with the U.S., the sale of any weapons, munitions, or dual-use technologies to China.

In this light, Israel’s engagement with the Chinese in other areas, from water and medical services in China itself to Chinese construction projects in Israel, should be seen not as leading Israel into the Chinese orbit but as an effort to keep Beijing contented while arming those in Asia who fear China’s ambitions. Once again, this sensible strategy ultimately serves U.S. interests as well. After all, the Trump administration, like its predecessors, has also come to recognize that the PRC, a foe in some respects, is in others a beneficial partner.

Ultimately, I concede, the validity of my argument stands or falls on one key criterion: namely, the degree to which the Chinese, whether as investors, infrastructure builders, or exchange students, will or won’t abuse their welcome to Israel by seeking access to sensitive systems and sowing the seeds of cyber subversion, thereby gaining priceless information on Israeli and American capabilities. Given China’s prowess in offensive cyber, as well as its long history of intellectual-property theft, the concerns voiced by Arthur Herman and others are perfectly appropriate.

That is why experts from both the U.S. and Israel need to cooperate intensely and openly on ways to contain and turn back any threat. Fortunately, the mechanism already exists. In placing limits on any Chinese intrusion, Israel’s lead in defensive cyber systems can be put to good use

More generally, what’s needed is a discerning and sophisticated approach that, while appreciating the major benefits that Israel can draw from greater Chinese involvement in the eastern Mediterranean, aims to build and maintain effective firewalls against potential abuse. In this connection, it might be worth forging more links not between Jerusalem and Beijing but between Israel and specific Chinese provinces, entities that by definition focus on legitimate civilian needs. Indeed, on November 1 a delegation led by Vice-Governor Zong Guoying of Yunnan was in Israel for the fourth annual Yunnan-Israel Innovation Cooperation Forum.

The more Yunnans, the better for everyone. This mode of cooperation, carefully nurtured even as Israel’s security relations with other major players in Asia continue to grow apace, is no challenge to U.S. policy. It is a useful auxiliary to that policy, and surely preferable to an “all or nothing” approach.

More about: China, Israel & Zionism, Israel-China relations