In “The Mirage of an International Jerusalem,” Michel Gurfinkiel brings to light—more vividly than in any other account I have seen—the long-forgotten connection between contemporary disputes over Jerusalem and the diplomatic fantasies of the late 1940s. I totally agree with his conclusion that there is no serious legal argument against foreign nations recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, just as the United States did in 2017. In this respect at least, we should be glad that President Trump is not much concerned with diplomatic niceties.

I am much more skeptical, however, of Gurfinkiel’s suggestion that if the history of this dispute were better understood, objections to Israeli control over a united Jerusalem would dwindle to harmless mutterings. Edmund Burke warned the revolutionists in France that overthrowing the ancien régime would not end injustice and oppression: “wickedness is a little more inventive.” Those who offer escapist plans for Middle East peace are also more inventive than Gurfinkiel seems to acknowledge.

With that in mind, I want to emphasize here how fantastical it was, even in the late 1940s, to imagine that peace could be established in the former territory of Mandate Palestine by placing Jerusalem—or a greater Jerusalem entity—under “international control.” As it happens, the world already had bitter experience of such schemes. They had quickly become too embarrassing for the “international community” to remember, but they remain object lessons for today.

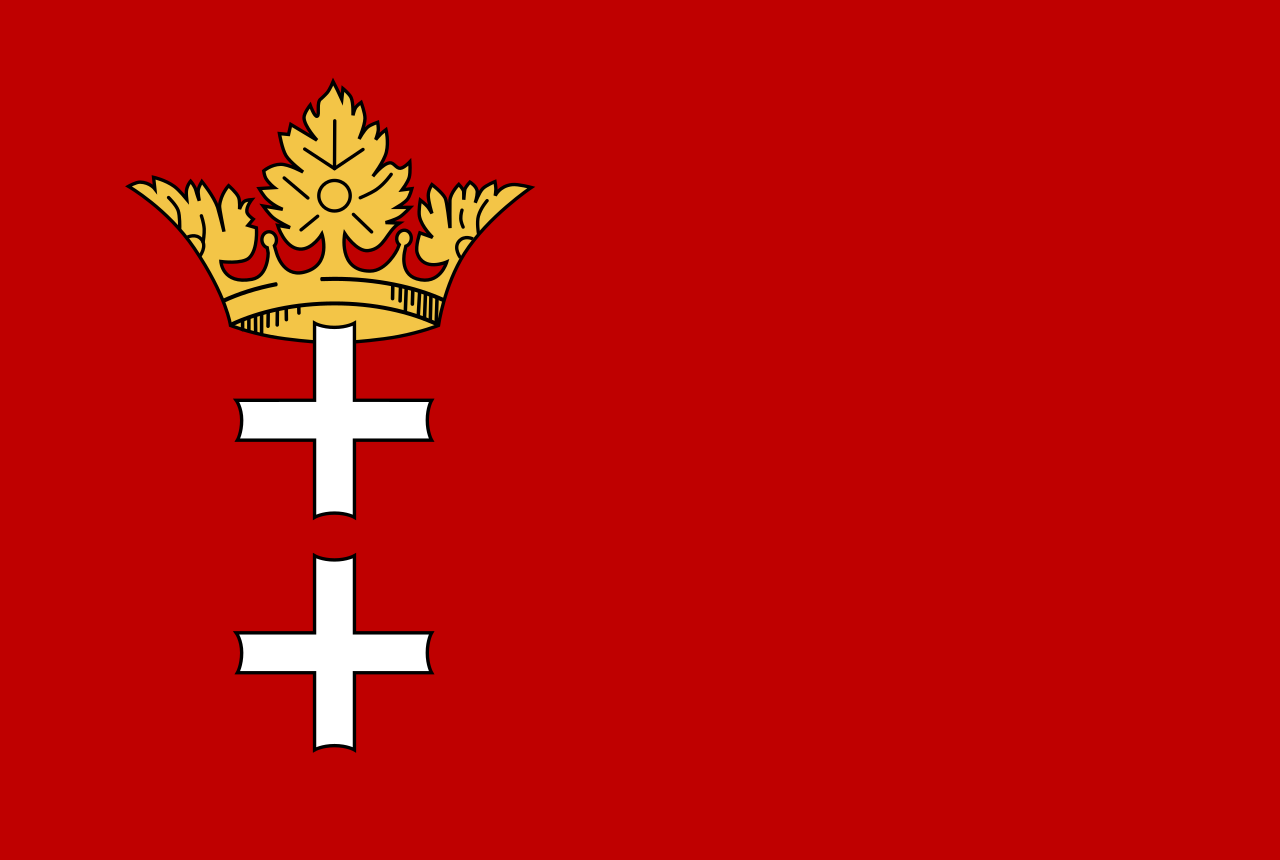

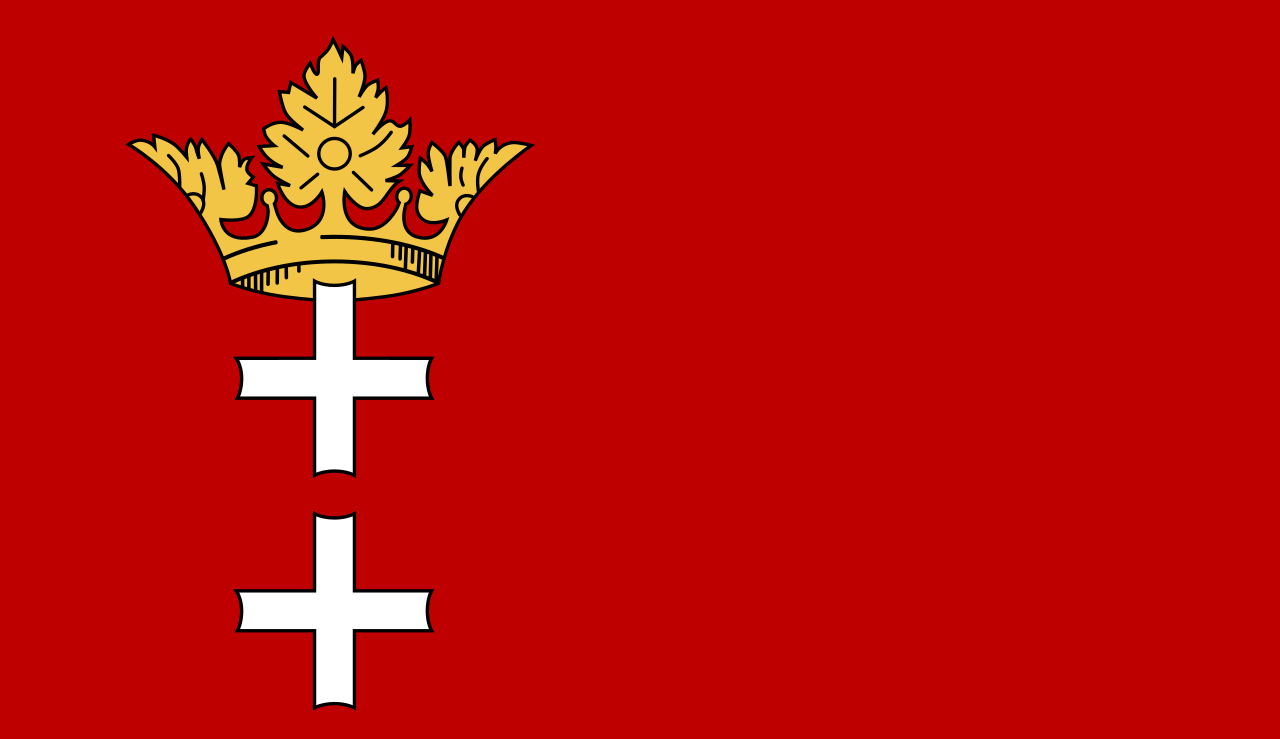

The most important such scheme was the Free State of Danzig, established after World War I by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles and then placed (as the peacemakers had envisioned) under the protective control of the League of Nations. The idea was to ensure access to the sea for the new, postwar Polish state by detaching Danzig from the defeated German empire while also mollifying the local, majority-German population. International supervision, exercised through a High Commissioner appointed by the League, was supposed to allow self-government by the German majority and simultaneously assure international protection for “minorities” (essentially, Poles and Jews).

In practice, by the early 1930s local Nazis had gained control of Danzig while Poland, for its part, had so little confidence in international guarantees that it built an entirely new port, Gdynia, on neighboring Polish territory. Only the Jews were left to solicit protection from the League—which did not provide it. Nazis in Danzig proceeded to expel Jews from public employment, to restrict their businesses, and then to launch a pogrom against Jewish homes and shops. All this, a year before Kristallnacht in Germany.

Danzig’s Jews were right to distrust and discount international guarantees. By 1939, some 85 percent of them had already fled. When, that year, Hitler demanded the repudiation of League controls over the territory, French appeasers raised the slogan, Pourquoi mourir pour Dantzig? (“why die for Danzig?”).

Many millions did die in Europe over the next six years, after which the Red Army provided a different solution: the city was handed to Poland, becoming postwar Gdansk. No one thought to offer guarantees for the small German minority that survived the ethnic cleansing at war’s end.

Another example: in the last days of World War II, British forces fighting their way up Italy’s Adriatic coast reached the multiethnic port of Trieste—at just the same time as Tito’s Communist partisans. Western diplomats were anxious to keep the Communists out while maintaining peace in a city still embittered by memories of ethnic and political repression under Mussolini’s dictatorship.

The result: another international-control regime that was supposed to operate under the supervision of the then-newly founded United Nations. But with Soviet delegates at the UN continually vetoing Western proposals, the regime failed to establish its authority. By the early 1950s, as Gurfinkiel notes, Trieste was handed back to Italy through an agreement by Britain and the U.S. with Italy and Yugoslavia—and without regard to the UN.

Finally, Berlin. Postwar agreements on that city never involved the UN. In fact, the occupying powers had taken the trouble to specify expressly in the UN Charter that treatment of Germany would not come under UN supervision. But even so, after citywide elections in 1946 (in which Communists did poorly), it became impossible for the Western and Soviet occupiers to maintain common governing arrangements as originally envisaged. With the Soviets refusing cooperation and imposing repressive control in their own sector, Berlin became a divided city, with the divisions cemented in 1961 by a wall. The Western allies were not prepared to risk war in order to maintain the free access originally promised.

For Jerusalem, too, the issue was always how to uphold the claims for internationalization. To maintain any agreed-upon terms would have needed an outside authority prepared to use force—and to incur casualties. There were no volunteers for this role.

After the 1948-49 war, Britain, the former Mandatory power, recognized the Hashemite kingdom of Jordan as the rightful sovereign in eastern Jerusalem: an urban area that had been seized during the hostilities by King Abdullah’s army. No one else (except Pakistan) recognized Jordan’s claims over this area, which included the Old City with its dozens of synagogues, most of them razed by the invading Arab army. Britain’s lonely stance reflected its own lack of interest in recommitting forces to the territory it had abandoned in 1948.

More recently, the hopelessness of international control in the Middle East has been illustrated by the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), a body tasked with guaranteeing that, following fighting on the Israel–Lebanon border, Hizballah would not be able to restock its rockets and weapons in that territory. But the (largely French) forces there have declined to confront Hizballah, leaving no meaningful constraint on the ability of that terrorist organization to rearm and reoccupy the region.

And yet, though our world can’t sustain “international” control in Jerusalem, most governments still don’t accept Israeli control as the inescapable alternative. True, it’s been many decades since a UN resolution has mentioned Jerusalem as a separate entity (corpus separatum) with a special international status, but resolutions since the 1970s have persistently denounced Israel’s presence in “occupied East Jerusalem” or “occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem.”

The Palestinian Authority never wavered from its position that the “two-state solution” must include a Palestinian capital in “East Jerusalem.” Even the usual capitalization of that “E” reinforces the otherwise fantastical notion that this portion of the city is already an entity rather than, like the supposed borders of Arab “Palestine” itself, a mere reminiscence of the 1948-49 battle lines.

It is not just European governments that remain entranced by this vision. In the early 1990s—as a friend in the White House told me at the time—top officials in the first Bush administration pored over maps trying to figure out plausible boundaries for a Palestinian capital to be carved out of Jerusalem. Almost three decades later, as another friend tells me, the Kushner team in the Trump White House has been puzzling over which adjacent villages might be presented as the “capital of the Palestinian state in East Jerusalem.”

I am not sure how many foreign states actually want to see the holy sites in Jerusalem under the control of a Palestinian government. To judge from past experience, such a government would likely be unstable, consumed by the need to outpace domestic challengers through demagogic gestures, and perpetually tempted to prove its power through reckless provocations. Indeed, it is notable (though rarely mentioned) that the mosques on the Temple Mount remain under the direction of a Jordanian-controlled foundation—without eliciting protest from states that ritually demand Palestinian sovereignty over “East Jerusalem.”

Over decades of intermittent peace initiatives, U.S. officials have repeatedly urged that final-status talks on Jerusalem be deferred to the last stages of negotiations. This remains good advice. If one actually thinks it plausible that Palestinian authorities and the government of Israel can agree on a mutually acceptable two-state solution, one may also imagine agreement on a formula for sharing Jerusalem. In the meantime, unless the Palestinian Authority decides to relinquish claims on eastern Jerusalem, most foreign governments will probably continue to dispute Israeli sovereignty over the whole city.

Yet that in itself, as Michel Gurfinkiel demonstrates, is no reason why they can’t also move their embassies to “Jerusalem.” The new U.S. embassy is in “West Jerusalem.” Foreign governments may call it whatever they like, but it is and always has been the capital of the state of Israel.

More about: International Law, Israel & Zionism, Jerusalem, United Nations