Michel Gurfinkiel’s essay in Mosaic on Jerusalem’s status in international law provides excellent insight into the incoherent approach adopted by many of the world’s governments to Israel’s sovereign rights in and to its own capital. His analysis is particularly fascinating in demonstrating the outsized role played by the Catholic Church since 1948 in the persistent demands for Jerusalem’s internationalization.

In what follows, I’ll explore further the convoluted case for special treatment of Jerusalem on the basis of international law—an inquiry that can teach us a great deal about international-law claims against Israel in general.

Gurfinkiel questions in passing whether international law even exists, but (as he also concedes) we need not linger over such ontological considerations. Just as debates over whether contemporary art is really “art” can be profitably set aside, at least initially, in favor of direct assessments of the aesthetic value and appeal of particular works, we can focus on concrete and self-styled applications of international law while stipulating for the purposes of discussion that international law does exist, although it is vague and provides far fewer conclusive answers than its acolytes claim for it.

International law certainly does exist on the issue of a new country’s borders. It is, moreover, fairly clear, and is applied almost across the board. But the “almost” is key: where Israel is concerned, and where the status of Jerusalem is concerned, what the UN claims international law says is not what it does say.

Thus, a cascade of UN resolutions has described as an “occupation” Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria (the West Bank): territories taken, or rather retaken, from Jordan in the defensive Six-Day War of June 1967. Between then and 2016, there were well over 2,000 such UN resolutions, most of them calling for an Israeli withdrawal to the pre-Six Day War “1967 lines.” Compare this with the UN’s treatment of actual occupations, including of Western Sahara and Northern Cyprus, against which the UN has likewise passed resolutions—sixteen, in all.

Where Israel is concerned, it cannot be said that these UN resolutions are based on international law. In fact, they contradict well-established and broadly applied rules for determining the borders of newly created countries. Under international law, when a new state comes into being—through decolonization, imperial collapse, secession, internal collapse, or otherwise—its borders are deemed to be the borders of the immediately prior top-level administrative unit in the territory. This is known as the uti possidetis juris (“as you possess under law”) doctrine. It has been used for centuries to determine the borders of new states around the world, and has been upheld by numerous international tribunals.

For example, as I’ve written elsewhere, the borders of post-Soviet states match exactly the administrative boundaries of the former Soviet “republics”—despite the fact that the latter had been drawn arbitrarily and capriciously by the Kremlin. The same can be said about many of the lands that, in the aftermath of World War I, came under the control of Mandatory powers (mainly Britain and France) appointed by the League of Nations. In the end, when these entities became independent states, their borders became the borders of the Mandatory territory at the moment of independence.

Crucially, uti possidetis trumps any contrary criteria for establishing borders, such as ethnic self-determination, natural boundaries, or historic title. That is because none of those factors provides a clear and determinate answer to the question of borders; relying on them would ineluctably lead to the boundaries of new states being regularly and violently contested.

Under the uti possidetis principle, then, Israel’s borders at the moment of independence are quite clear: the borders of Mandatory Palestine. Those borders include all of Jerusalem, and Judea and Samaria as well. The UN, in its thousands of resolutions to the contrary, flagrantly ignores that principle.

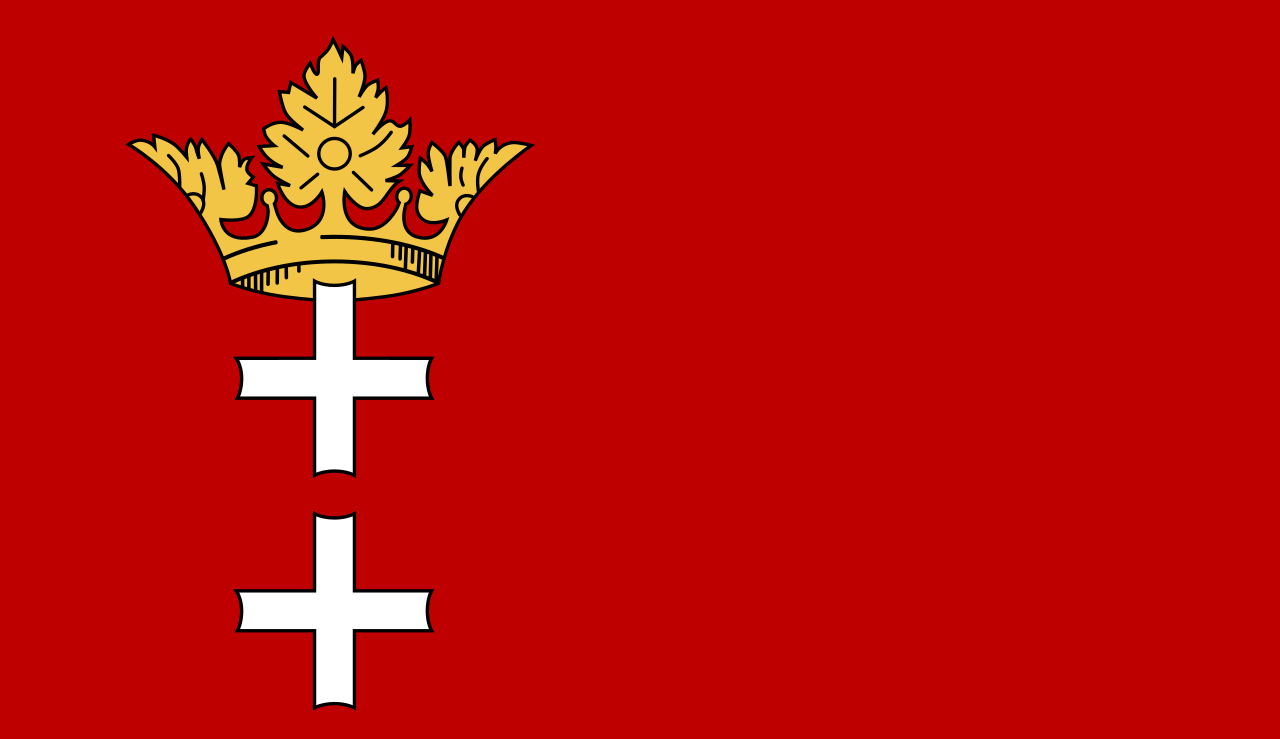

This conclusion is not affected by the UN General Assembly’s partition proposal, adopted as Resolution 181 in November 1947, that provided for the formation in Palestine of two states, Jewish and Arab, with the city of Jerusalem designated a separate internationally-administered entity (the corpus separatum). That is not only because the UN proposal was a non-binding recommendation, but because, having been rejected by the Arabs, it was never implemented and did not in fact result in a partition of the Mandate. Uti possidetis goes by the prior administrative borders as they were, not as they might at various times have been imagined to be.

Nor were Israel’s borders changed when, in its 1948-49 War of Independence, some of this territory, including parts of Jerusalem, was seized by Jordan. This is because of the general principle in modern international law that a country’s sovereign territory cannot be taken in an aggressive war; the invasion of Israel by five Arab countries in May 1948 with the declared aim of destroying it was emphatically such a war.

What all of this means is that under the straightforward application of general international-law rules, Israel had sovereign title over all of Jerusalem and Judea and Samaria from 1948. Therefore, in 1967, Israel was not conquering this territory but merely liberating it. The many calls by the UN for Israel to return to the “1967 lines” do not apply international-law rules to Israel but rather disregard those rules altogether in favor of a tailor-made set of rules that apply to Israel alone.

Nor does the double standard stop there; to the contrary, it re-doubles itself.

Even as the UN insists on limiting Israel to the fictitious pre-June 1967 borders, when it comes specifically to Jerusalem, it unceremoniously abandons that position and proposes to deduct an additional and no less arbitrary slice of land from Israel’s sovereign territory. It does so once again by invoking the “internationalization” provisions of Resolution 181. But those borders have no legal force, for all of the reasons Gurfinkiel cites in his essay and that I have amplified here. And the UN’s insistence on Resolution 181 also contradicts the supposedly sacrosanct status of the “1967 borders” themselves, since much of the city lies within those same borders.

Worse, although Resolution 181 is invoked to limit Israeli claims to Jerusalem, it is not understood to limit Palestinian claims. Quite the contrary: UN Security Council Resolution 2334, adopted just three years ago in the waning days of the Obama administration, describes “East Jerusalem,” which includes the historic Jewish quarter of the Old City, as “occupied” “Palestinian territory”—in direct contradiction of the corpus-separatum principle that, as we’ve just seen, is invoked to deny any Israeli sovereignty over Jerusalem.

Moreover, as Gurfinkiel notes, the “Jerusalem” of Resolution 181 was much larger than the present-day municipality, including as it did much of Bethlehem. Yet Bethlehem, too, is treated by the UN as indisputably “Palestinian” territory.

In sum, if the insistence on Israel’s limitation to the pre-June 1967 lines is a departure from general principles of international law, the denial of its sovereignty is an additional departure, and one that is logically at odds with the first. Call this a quadruple standard: a double standard within a double standard. There is no rhyme or reason behind it—only anti-Israel bias.

With all of this in mind, we can now return to the question of whether international law exists. Surely it does, but not everything that is passed off as international law qualifies as international law. The UN General Assembly has, by the UN’s own Charter, no power to make any binding decisions whatsoever. The Security Council does have real power, but far less than is commonly assumed. In the case of a breach of international peace, it has the power, when acting under Chapter VII of the Charter, to authorize enforcement actions, including economic sanctions and the use of force.

In U.S. constitutional terms, this is essentially an executive function. The Security Council is emphatically not an international legislature: it does not have the power to rewrite international law, let alone to make a special law for a particular country. Nor is it an international court: it cannot make binding determinations about the content of international law. It is free to offer up, as recommendations, its opinions about the content of international law and its application to particular cases. But others, including Israel, remain free to test the validity of these claims. If the principles endorsed by the Security Council in the case of Israel contradict international law as it applies to other countries, they do not become more valid by dint of a vote in the Security Council.

Law, as Friedrich Hayek explained, is a system of general rules promulgated for unknown future cases. As we have seen, the UN’s judgments on Jerusalem do not comport with the general rules. Rather, they are at best fiats, particular decrees directed solely at Israel that are delivered ultra vires (beyond granted powers). In that respect, too, they are neither international nor are they law.

There is no parallel to the international fixation with the non-binding, long since moot, and moribund Resolution 181, and the same can be said for Security Council Resolution 470, cited by Gurfinkiel, that in 1980 denounced Israel’s parliament for a law enshrining Jerusalem as the country’s capital. In numerous other contexts where the UN has expressed an opinion about a desired resolution to a territorial conflict, that opinion is not regarded as a permanent divine dictate once events have rendered it moot.

Indeed, the same year the General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, the Security Council passed a resolution that, rather than merely contemplating an “international city,” actually created one: the “Free Territory of Trieste.” That “permanent” arrangement ended with the unceremonious annexation of the territory by Italy and Yugoslavia. Who today recalls Security Council Resolution 16 for the purpose of questioning Italian or Croatian sovereignty over the defunct Free Territory?

Similarly, Security Council resolutions from 1948 about the partition of Kashmir have been ignored in every respect and inform nobody’s present understanding of India’s borders. Kofi Annan himself, the former UN secretary general, noted that the Security Council’s Kashmir resolutions were not clear mandates and not “self-enforcing.” That much of the world sees a mere General Assembly resolution of the same vintage as binding on Israel (but not on the Palestinians) says a great deal about international politics, but nothing about international law.

More about: International Law, Israel & Zionism, Jerusalem