In his essay “Confrontation,” the great Talmudist and philosopher Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik responded to the mid-1960s advent of the Second Vatican Council by emphasizing that certain root theological concepts—like, for instance, “covenant” and “election”—are approached by different faiths through the lens and language of their respective religious experience. Therefore, he wrote, while Christians and Jews should discuss certain matters of vital concern to both communities, no good could come of their debating or entering into “public dialogue” about core theological issues.

For the same reason, I would certainly not undertake to instruct Gavin D’Costa, or Catholics in general, on how they should think theologically. Instead, drawing on D’Costa’s eloquent essay in Mosaic on Catholic Zionism, I hope in what follows to reflect upon where, from my own perspective, Catholic theology presently finds itself on the subject of the state of Israel, and where it might find itself in the future.

For centuries, Church theologians were largely united on the premise that all eschatological predictions in the books of the Hebrew prophets that invoked the restoration of Zion were to be read not literally but as referring proleptically to the Church. Thus, when, in an episode cited by D’Costa, Pius X refused to consider Theodor Herzl’s request for Vatican support of a Jewish return to the Holy Land, the pope was not merely expressing a skeptical disdain for the right of Jews to aspire to the status of a nation but drawing on a long tradition of biblical exegesis.

The Church historian Robert Louis Wilken has described the evolution of that tradition in these words:

In disputes with Jews, Christian thinkers in the early centuries argued that the promises of return and restoration (in Isaiah, Ezekiel, and the minor prophets) must be interpreted to refer either to . . . the time of the return from exile in Babylonia [in the 6th century BCE] or to the new gathering of humankind in the Church.

In the 5th century [CE], St. Jerome, who was living in Palestine, carried on a running debate with Jews in his biblical commentaries on the interpretation of the prophecies of return and restoration. Jews took them to refer to a future rebuilding of the cities of Judea as Jewish cities and to the reestablishment of Jewish rule in Jerusalem, while Jerome saw them as fulfilled in the coming of Christ and the new reality of the Church.

Today, however, it would seem very strange to contend that the Hebrew Bible’s predictions regarding Zion are not to be taken literally. After all, many prophetic scenarios—of the desert blooming, for instance, or of Jerusalem filled with Jews—have actually come to pass. True, the wolf does not yet lie down with the lamb, and the Temple has not yet been rebuilt; but one cannot read the prophets without thinking of present-day Israel, and one cannot visit present-day Israel without thinking of the prophets.

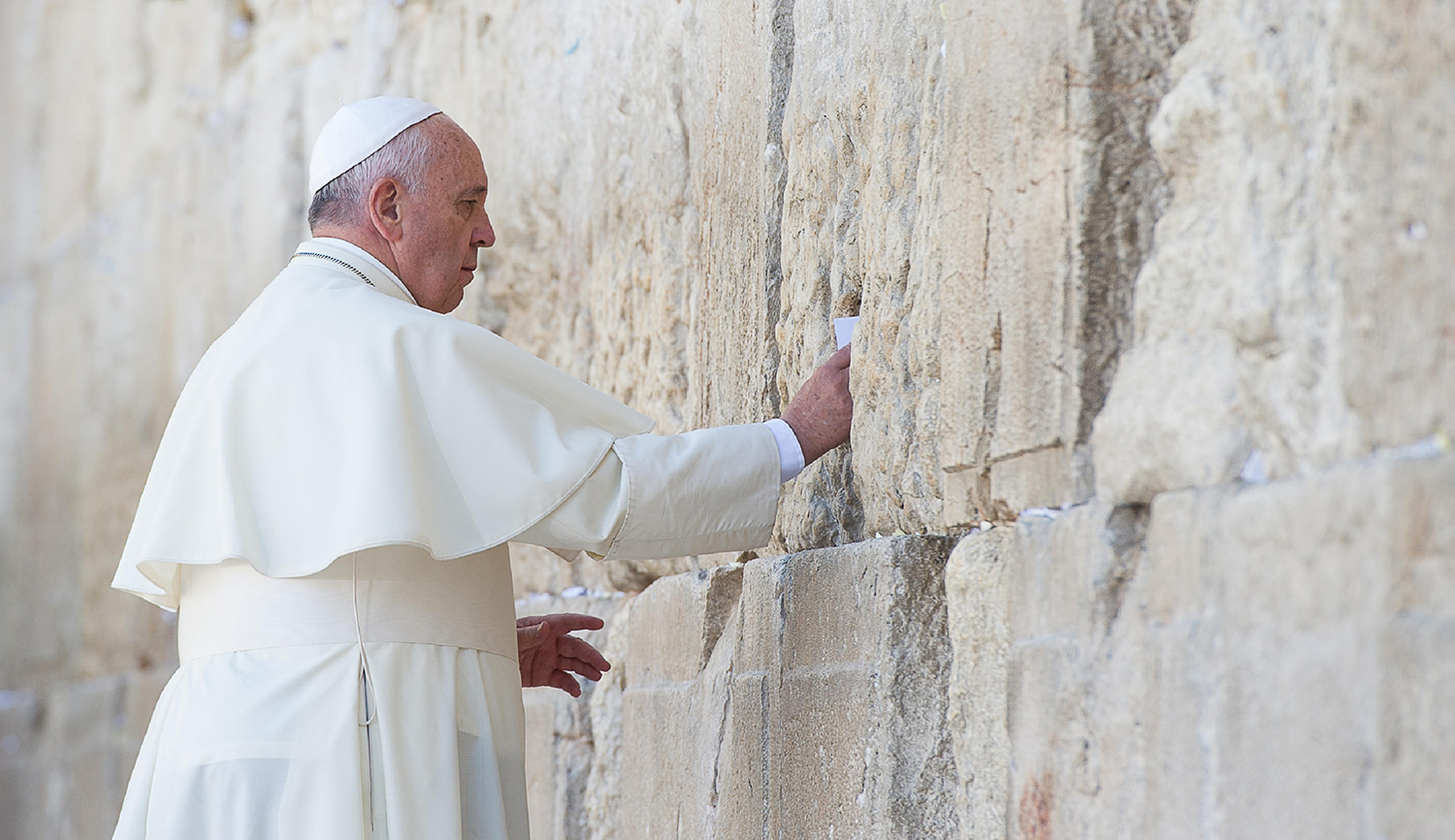

Truly, as Isaiah described, “the Lord has consoled Zion,” has “made her desert into an Eden, and her wilderness into a garden of God.” One cannot attend a wedding in Israel without being reminded of Jeremiah’s assertion that “there will yet again be heard, in the cities of Judah and the outskirts of Jerusalem, the sound of jubilation and joy, of groom and bride.” One cannot exit Yad Vashem, with its soul-searing exhibits of the Shoah, and behold Jerusalem rebuilt without thinking of Ezekiel’s vision of the “valley of the dry bones,” or spend a Sabbath at the Western Wall without being reminded of Zachariah’s promise of grandparents enjoying the sight of their progeny at play in the streets of Jerusalem.

Nor are religious Jews the only ones to feel this way. Recognition of the literal fulfillment of Hebrew biblical prophecy is a foundation of evangelical Christian Zionism.

The story of the state of Israel therefore poses a striking theological challenge to those who still decline to see the living Jewish people in the predictions of the Jewish prophets. Indeed, Rabbi Soloveitchik himself went so far as to say that one miracle manifested in the birth of modern Israel lay in the fact that the purely allegorical or symbolic reading of these Hebrew verses had now been disproved.

Through the birth of Israel, he proclaimed in a famous speech on Zionism, the notion “that the Holy One ha[d] taken away from the Community of Israel its rights to the Land of Israel, and that all of the biblical promises relating to Zion and Jerusalem now refer[red] in an allegorical sense to Christianity and the Christian Church,” had been “shown to be false.” One must, he added, “have a broad familiarity with theological literature from the time of Justin Martyr down to the theologians of our own day to comprehend the full extent of this marvel.”

Hence, to ignore what the existence and flourishing of the Jewish state of Israel signify for the interpretation of the Hebrew prophets is to ignore the hand of God in history. And this brings us to one of the documents on which D’Costa focuses his own analysis: the 1993 “Fundamental Agreement” between Israel and the Holy See.

D’Costa points to the passage in the agreement’s preamble citing the “unique nature of the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Jewish people,” which he sees as suggesting an implicit linking of the people with the state. Yet even as it does recognize the theological significance of the Church’s engaging with the Jewish people anew, the agreement studiously avoids any reference at all to the religious significance of the reestablishment of the Jewish state in the land, or to the extraordinary achievements of the Jews in that land.

Strikingly, indeed, none of the sources cited by D’Costa in his essay, with the possible exception of remarks made by John Paul II to the Jewish community in Brazil, quotes from or cites the now-fulfilled prophetic descriptions of the Jewish return to the land promised to Abraham. The Fundamental Agreement, even as it marks an important step forward in Catholic-Jewish relations, simultaneously seems to ignore the theological elephant in the room.

What does this portend for an emerging or future Catholic position vis-à-vis the land and the state of Israel? I cannot say for certain, but as an interested and theologically engaged outsider I see two different trends at work today among Catholic intellectuals, writers, and theologians.

One trend consists of those who have been inspired by Israel to read the Bible with fresh eyes. A striking exemplar is Cardinal Cristoph Schoenborn, the archbishop of Vienna and one of the Church’s most important theologians. This is from the Washington Post’s report of a 2007 speech by Schoenborn on a visit to Israel:

After asking, “What does Eretz Yisrael [the Land of Israel] mean to us,” Schoenborn answered by stressing the doctrinal importance to Christians of not only recognizing Jews’ connection to the land but also ensuring that Christian identification with the Jewish Bible not lead to a “usurpation” of Jewish uniqueness.

“Only once in human history did God take a country as an inheritance and give it to His chosen people,” Schoenborn said, adding that Pope John Paul II had himself declared the biblical commandment for Jews to live in Israel an everlasting covenant that remained valid today. Christians, Schoenborn said, should rejoice in the return of Jews to the Holy Land as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy.

So that is one possibility. The miracle of Israel, and the very obvious fulfillment of Isaiah’s words, could inspire a deep rethinking of Catholic theology by members of the episcopacy itself. The birth of such a true Catholic Zionism should be and certainly would be welcomed by most Jews as a blessing, just as, in my view, Christian evangelical Zionism is already a great blessing.

There is, however, another, much more ominous possibility. The great Jewish religious thinker Franz Rosenzweig once reflected that hatred of Jews draws on the unconscious realization of the challenge posed by Jewish eternity to the exclusive truth claims of Christianity. Just so, the theological challenge posed by the existence and the achievements of the Jewish state could lead some Catholics to take up an adversarial position toward it both philosophically and politically.

Here is how Rosenzweig characterized the syndrome:

The existence of the Jew constantly subjects Christianity to the idea that it is not attaining the goal, the truth, [and] that [Christianity] ever remains on the way. That is the profoundest reason for the Christian hatred of the Jew, which is heir to the pagan hatred of the Jew. In the final analysis, it is only self-hate, directed by one’s own existence; it is hatred of one’s own imperfection, one’s own not-yet.

More recently, the Catholic thinker Eve Tushnet has put the point like this:

The Jews are the consistent sticking point in every Catholic political fantasy. . . . And every reimagining of Catholic politics which is not explicitly and uncompromisingly opposed to Jew-hate will be slowly corroded by it.

Consciously or unconsciously, the theological challenge posed by Israel could thus motivate some to discredit and demonize Israel, to deprecate it as less than the miracle it is. I cannot say that such an approach has prominently manifested itself, but there are, here and there, disturbing signs.

Among some of those affiliated with what has been termed “Catholic integralism,” for example, one can find a certain readiness to embrace the anti-Zionist narrative, to repeat and to circulate criticisms of Israel if not to embrace anti-Zionism entirely, sometimes cloaked in celebrations of the virtues inherent in ethnically diverse Catholic empires of the past as opposed to the alleged vices and drawbacks of contemporary national states built around ethnic identities.

Where exactly this is heading I cannot predict, but, at the very least, it would be incorrect to claim, or to believe, that all prominent Catholic intellectuals are moving in a pro-Israel direction.

A purely neutral approach to the Jewish people’s return to the Land of Israel, and to Jerusalem, is theologically unsustainable. A faith that accepts the predictions of the Hebrew prophets as the word of God cannot ignore the seeming fulfillment of that word. It will either—as tens of millions of American evangelicals have done—embrace this fulfillment of God’s word as a source of faith itself or it will turn against the state whose birth, existence, and flourishing have been hailed by the Catholic historian Paul Johnson as the only true political miracle of the 20th century.

Which course is taken by the Church, by Catholic thinkers, bishops, and of course popes will help determine the Catholic future.