I’m grateful to Daniel Johnson, Kevin J. Madigan, and Meir Soloveichik for their thoughtful and engaging responses to my essay in Mosaic arguing the case for an emergent form of Catholic Zionism.

In what follows, I’ll begin with Kevin Madigan’s ingeniously imagined discussion of my thesis, staged between a traditionalist Catholic whom he’s dubbed “T.” and T.’s more liberal Catholic friend “R.” I need to address this first lest Madigan succeed in pulling the theological carpet from under my feet (or my footing). Here and elsewhere in this reply, I’ll also be engaging in a certain amount of “theology talk,” for which I beg the reader’s indulgence.

Are the Church’s recent teachings on the Jewish people theologically legitimate? Madigan’s T. (the traditionalist) holds that, to the contrary, they are utterly discontinuous with previous papal and conciliar teachings that Judaism is invalid because the Jews rejected Jesus, thereby losing God’s gifts and promises of salvation. How is it possible, asks T., for Judaism suddenly to be declared valid after all? Either previous popes were wrong, or recent and present popes are wrong. Both cannot be right.

I agree. The teachings of today’s magisterium cannot be regarded as authoritative if those teachings run counter to what the very same magisterial authority said in the past. Whatever Catholic theologians may hold about certain traditions and practices—including, and I don’t say this lightly, the many anti-Jewish traditions and practices of the past—T. is right that Catholics are bound to honor formal, authoritative magisterial teachings “in the same meaning and the same explanation with which the Church has always communicated them.”

Where, then, do T. and I disagree? Answer: on the issue of whether or not, in the past, the formal Catholic magisterium may itself have underwritten contrary teachings.

Consider one often-cited example: the mid-15th-century Council of Florence, which solemnly taught that “the holy Roman Church . . . . firmly believes, professes, and preaches”—the formula that makes this a high-level magisterial teaching—“that no one remaining outside the Church, not only pagans but also Jews [Iudeos], heretics, or schismatics can become partakers of eternal life, but they will go to the ‘eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.’”

I take this teaching to be formally binding, as I’m sure T. does as well. But here’s the question: are the “Jews” in that sentence the same Jews about whom the mid-20th-century Second Vatican Council would make such authoritatively affirmative comments? I think not, for reasons related to the language, meaning, and intention of the two magisterial statements.

At the risk of being called “Jesuitical,” allow me to summarize. The pagans, heretics, and schismatics cited in the earlier teaching were all viewed as guilty—“culpable,” to use the technical term—of knowing the life-giving truth of Christianity but willfully refusing to accept it or to remain faithful to it. But to apply this specifically to all Jews always and everywhere, T. would have to know all Jews to be “culpable” of not being Christian! Given the persecution of Jews by so many Catholics throughout history, Catholic truth does not exactly shine out as an attractive truth for them to have known.

There is a double bind here. For if, by becoming Catholics, Jews were to lose their Jewish identity, they would also lose their already truthful relationship with the God of Israel. Pope Benedict XVI called Jacob Neusner’s A Rabbi Talks with Jesus (1993) “the most important book for the Jewish-Christian dialogue in the last decade,” especially in “allow[ing] the Christian world to look respectfully at this obedience of Israel”: an “obedience” expressed in, among other things, the principled refusal to accept Jesus as messiah. In so saying, the pope was clearly referring to Jews in a different sense from the one in earlier Church documents.

Should the bishops of Florence therefore have deemed the Jews “inculpable” because, unlike heretics and schismatics, they assuredly did not already know the truth of the gospel in their hearts and minds? To ask the question is to answer it; for the Florence bishops, an inculpable Jew was unimaginable. We can therefore accept that in this instance the bishops were wrong in lumping the Jews with the other three groups—which is a judgment regarding their practical reasoning, not a doctrinal judgment per se. Doctrinally, their focus was on the centrality of Christ and the Church for salvation.

Five centuries later, the bishops of Vatican II would view adherents of non-Christian religions as “not yet” [nondum] knowing the truth of Jesus Christ, the term used in the most authoritative document on this matter (Lumen Gentium, 16). In this sense, what the Council of Florence said about salvation was also said at Vatican II: salvation comes from Christ and his Church, because both are from God—although in different ways.

One last note here: significantly, the Vatican II bishops never attended to how the not-yet-knowing of non-Christians would ever be resolved, or indeed how whole religions could coherently be classified in the “not-yet” category. Where the Jews are concerned, this has led to the almost clumsy, but necessary, claim in the 2015 document prepared by the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews:

That the Jews are participants in God’s salvation is theologically unquestionable, but how that can be possible without confessing Christ explicitly is and remains an unfathomable divine mystery.

This contortion exemplifies a church wrestling with its traditions while also facing the fact of tradition’s development. The first half of the sentence quoted above would have been inconceivable for most of the Church’s history. The second half raises the question of whether one can ever explain unfathomable divine mysteries or instead must take cover under their claimed existence when something deeply paradoxical or contrary appears.

I could present more examples showing how more recent formal papal teachings on the Jews—there aren’t that many—can be construed to address the Jews of Vatican II. They are detailed at length in my forthcoming book, Catholic Doctrines on the Jewish People after the Second Vatican Council (Oxford). As history teachers know, the study of context, time, and presuppositions helps us properly interpret texts.

And this brings me to “R.,” the other character in Madigan’s staged dialogue. A Catholic reformer, R. nevertheless sympathizes with T.’s frustration and admits to being at a loss on the issue of how far reform itself can be legitimately carried and where it will end. Recalling a question raised in his graduate seminary, “What are the controls on unlimited revision of Church teaching?,” R. writes: “It confounded me then, and still does.”

To R. I would therefore suggest that reform does not preclude or abridge continuity. Pope Benedict, often seen as an arch T.-type, asserted in 2005 that reform and the development of doctrine are in fact central to the Church, but always out of its genuine traditions. He acknowledged the inevitable tensions arising out of this exercise (tensions that, in one way or another, preoccupy every faith tradition today) by insisting that reform be understood as a “process of innovation in continuity.” In theory, then, R. and T. need not be divided but can even be united. The same can be said for previous vs. modern magisterial teachings on the Jews.

In contrast to Kevin Madigan, Daniel Johnson is comfortable with the theological aspects of Catholic Zionism but asks a series of probing questions about the Catholic Church’s recent actions, and whether these might signal a long wait ahead for any such movement to emerge. He may be right, and I’m no prophet. But as a Catholic theologian I have faith in good arguments and their purchase on the Catholic mind.

In this same spirit, I would also contest some of Johnson’s more alarmed readings of the runes. In particular, he worries that Pope Francis is not working with the same forward momentum as the previous two popes, Benedict XVI and John Paul II. Citing a series of symbolic actions taken by Francis in his 2014 visit to the Holy Land, Johnson discerns an apparent prioritizing of the Palestinian cause. Thus, he writes, Francis stopped to pray by a section of the separation wall between Israel and the Palestinian Authority that bore graffiti like “Apartheid Wall,” an image in deep contrast with John Paul II’s praying at the Western Wall. Also, in contrast to the two earlier popes, Francis visited the West Bank before visiting Israel.

If these were Francis’s only actions, there might indeed be cause for worry, but they weren’t. During the same visit, the pope made remarkable symbolic gestures that advanced Catholic-Jewish understanding. Most significantly, he laid a wreath at the grave of Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism. No other pope has even visited Herzl’s grave.

In this single gesture signifying Catholic support for Herzl’s vision of the Jewish homeland, Francis redressed the balance that a century earlier had been tipped in the other direction by Pope Pius X’s treatment of Herzl himself in 1904, an incident discussed in my essay. Moreover, Francis’s action unambiguously endorsed not only Israel’s right to exist but also the importance of its self-determination as a specifically Jewish nation.

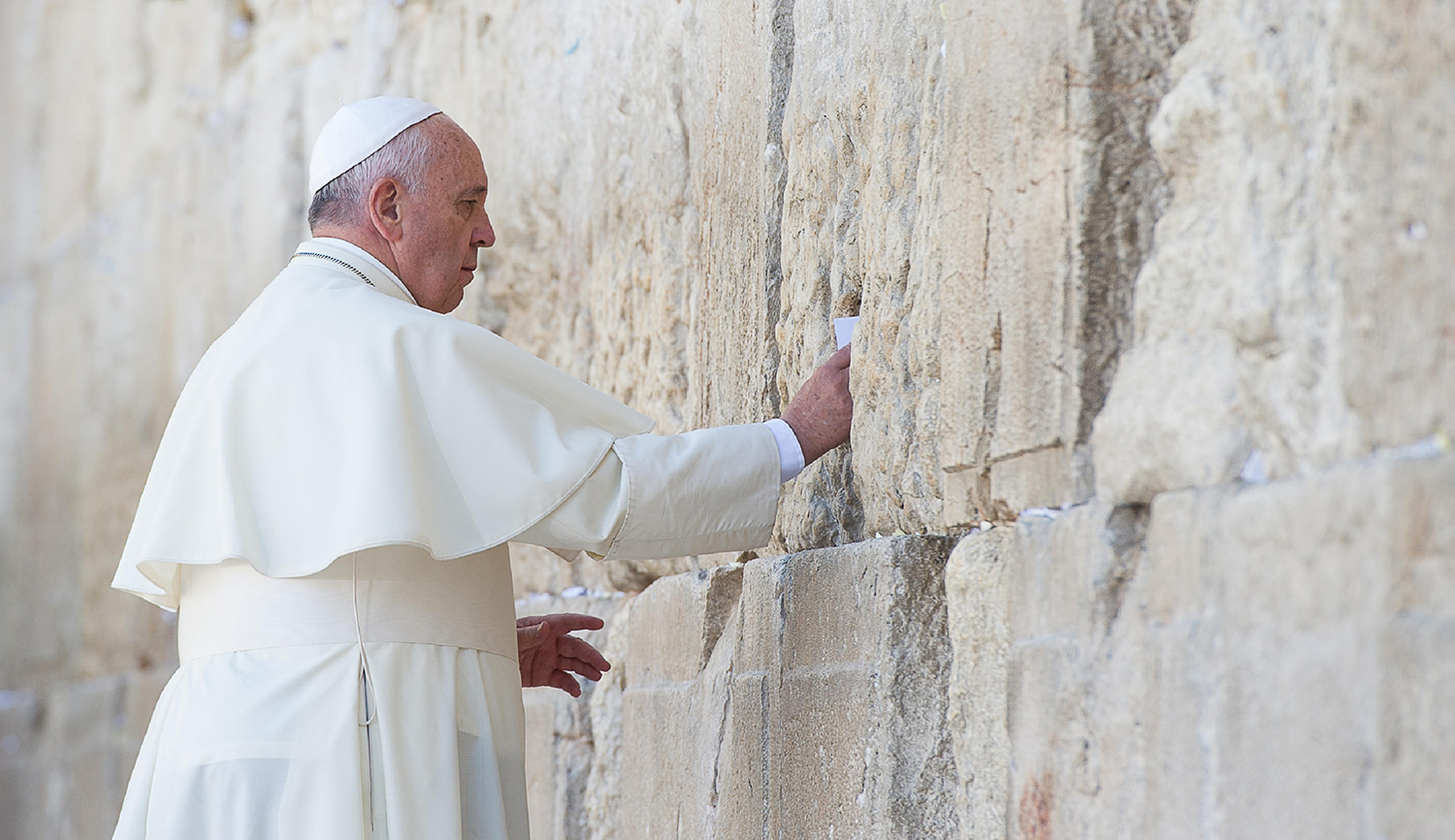

While at Mount Herzl, to offset his unscheduled stop at the separation wall, Francis, accompanied by Prime Minister Netanyahu, stopped at the shrine for those Jews, including in his own native Argentina, who had been killed in terror attacks. Like his predecessors, he also prayed at the Western Wall, honoring the ancient Temple and the religious life of Jews in Israel and thereby deepening a growing veneration for the holiness of the land itself—another issue discussed at length in my essay.

Once again like his predecessors, Francis also visited Yad Vashem, the museum of the Shoah, and there listened to six survivors speak. He was visibly moved by the testimonies, was reported to utter “never again, never again,” and kissed each speaker’s hand (thereby providing an image that many traditionalist Catholic websites would use against him). Cumulatively, all of these gestures show a deepening appreciation and support of Israel—and, I contend, a delicately emerging Catholic Zionism.

Lest I be misunderstood, let me underline two further points raised by Daniel Johnson’s concerns. This emergent Catholic Zionism is not contrary to, or negated by, Vatican support for the Palestinians and their right to a state; but neither is that latter support to be confused with the actions or ideas of those Christians for whom support of the Palestinian cause entails the elimination of Israel as a Jewish state.

Of course, establishing who represents the Palestinians and whether one can trust leaders who only yesterday or still today have been committed to the extinction of Israel is a real issue; many of the great and good have fallen trying to work this out. Catholic Zionists will always stand by Israel, even as they will also insist on a mature relationship in which the respective parties are fully entitled to pose critical questions to one another, and to answer them.

Finally, Johnson mentions a cardinal of his acquaintance who feels Catholic Zionism is an oxymoron, conflating a spiritual doctrine with a secular ideology. That cardinal is not alone, but whether this is a cause for pessimism is another matter.

Much of the early history of political Zionism was nourished by the inescapable association of its cause with millennial spiritual longings astir in the minds and hearts of Jews. Meanwhile, and in reaction to Zionism, many (though not all) pious European Jewish leaders rejected the movement for reasons analogous to those of the cardinal, as did some pious Jewish communities in pre-state Palestine itself. Generally speaking, indeed, it was only after 1948 and then 1967 that most (if not all) specifically religious critiques of Zionism—not to mention the hesitations and objections raised in secular precincts of Diaspora Jewry—fell away. With this in mind, Catholic cardinals might also be allowed a period of gestation, or grace.

Part of the difficulty here is the polysemic nature of Zionism, whose ranks have historically encompassed agrarian reformers, cosmopolitan socialist ideologues, right-wing hawks, left-wing peaceniks and pacifists, atheists and fervent religious mystics. Similarly with the ranks of those Jews who reject Zionism, some on grounds that might well be voiced by some veteran Zionists themselves.

Daniel Johnson is of course correct that one should not underestimate the amount of time, or the occasionally painful discussions, that could accompany the evolution of a fully fledged Catholic Zionism. One must be patient. But faith and miracles worked to make the Second Vatican Council’s Nostra Aetate a reality when the obstacles against it were equally formidable, if not more so.

From his own vantage point, Rabbi Meir Soloveichik offers telling observations about the state of play in Catholic circles on the Zionist question. Essentially, he sees “two different trends at work today among Catholic intellectuals, writers, and theologians.” Adherents of the one, encapsulated in what I have called Catholic Zionism, have in his words been “inspired by Israel to read the Bible with fresh eyes” and to see in Israel the fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Adherents of the other are moving in the opposite direction: toward a distancing from Israel or even an embrace of the anti-Zionist narrative. As between these two positions, for the Church itself to remain neutral is, he writes, “theologically unsustainable.”

I have some minor concerns with this otherwise helpful and illuminating map. But here I want to focus on the issue of biblical prophecy. Soloveichik sees in the emergence and flourishing of the state of Israel the seemingly self-evident reality of biblical prophecy “fulfilled.” His examples—the blooming of the desert, the resurgence of Jewish religious expression, the everyday life of a people marvelously revivified as in Ezekiel’s vision of dry bones putting on human flesh—are at once powerful and moving.

To this theological reading, I would pose two questions. The first relates to the details of prophecy, the second to hermeneutics, that is, to the methods of interpreting prophecy.

First: is this unquestionable return of the Jewish people to the land the return—i.e., the final return—or a return? For it to be the actual fulfillment of biblical prophecy, the answer would have to be the former. The difficulty with that scenario, from a Catholic Zionist perspective, is that it fails to take seriously the biblical warning of what would happen should the returning Israelites practice the same idolatrous “abominations” practiced by the land’s previous inhabitants. Their punishment is spelled out in these words: “the land will vomit you out . . . as it vomited out the nation that was before you” (Leviticus 18:28).

To be sure, thanks to the unconditional gift and promise made by God to the people Israel, this would not mean an exile from the land forever. But is it not premature to presume that it cannot happen? One should hope and pray, as I hope and pray, that modern Israel will never suffer the dire fate threatened in Leviticus, and I certainly distance myself from those who criticize Israel because it is a secular nation and thus cannot keep faithful to God. But the biblical account does suggest that the process of Israel’s becoming faithful is long and tortuous and follows no clear linear pattern.

In any case, there are other detailed elements that according to biblical prophecy must take place before a confident claim of fulfillment can be made. Soloveichik himself acknowledges some of these missing elements: the wolf does not yet lie down with the lamb, the Temple has not yet been rebuilt. Furthermore, the moral and cultic purity of the people is not yet self-evident.

The confidence with which Soloveichik speaks is thus something I envy but find difficult to share. Despite the many signs that the people in the land are part of God’s promise and clear evidence of God’s care for His people, for this Catholic to move up the eschatological ladder of prediction to affirm “fulfillment” is a step too far. Perhaps, instead, we might agree that even if this return should not eventually count as the “fulfillment” of prophecy, it is a proleptic witness to that longed-for fulfillment that will happen in the future.

Second, on the matter of biblical interpretation: up to now I’ve been granting the premise that all biblical prophecy is to be taken literally. What about that premise? Catholic exegesis in the past has been guilty of evaporating the literal into the symbolic and, in the process, of erasing the Jewish people and replacing them with itself. But should overcoming that error require an uncritical return to literal interpretation?

This brings us to an essential difference between the maximalist Zionism of Protestant evangelical Christians and what could, in contrast, be termed a minimalist Catholic Zionism. Soloveichik applauds the evangelicals, for whom, as he writes, “the literal fulfillment of Hebrew biblical prophecy is a foundation” of their Zionism. But take the New Testament book of Revelation, that most elliptical and fantastical of Christian canonical texts, and one that is central to evangelical Christian Zionists. Some number of evangelicals literally believe, on the basis of their reading of Revelation, that Christians will be taken up into heaven while the Jews battle it out with the anti-Christ. Some also believe that the Jews who survive this terrifying battle will convert to Christ.

Since these particular literal predictions are based elsewhere than in the Hebrew Bible (or “Old Testament”), I can safely presume they are not accepted by Soloveichik. But similar exegetical issues do affect Catholic vs. Protestant interpretations of parts of the Hebrew Bible itself. This is especially so in relation to end-time issues like the status of the physical Temple in Jerusalem and of the twelve tribes of Israel; regarding the latter, many Catholic exegetes argue that the tribes simply do not now exist, while some Protestant groups hold they will reappear in all of their individual distinctiveness. Without some commonly established hermeneutical approach, exegetes will remain divided in their interpretations and, if they are Zionists, in the nature and quality of their Zionism.

This leads me to a closing comment. Soloveichik rightly says that Catholic neutrality on Zionism and the state of Israel cannot be theologically sustained. Indeed, the Catholic Church can no longer step back from this issue. The 2001 document produced by the Pontifical Biblical Commission, to which I refer in my Mosaic essay, moved the process forward in acknowledging the truth of God’s promise to His people regarding the land. From other magisterial texts and actions, there are indications that this same promise is seen as taking shape in present-day Israel.

Yes, Catholics must eventually decide—if only because they, unlike deists, firmly believe that God acts in time and space, in our human history. Is God acting providentially in the emergence of Israel in 1948? I think so, and I think the Catholic magisterium is pointing toward that answer as well.

My sincere thanks once again to my three respondents for providing such good company in grappling with these issues.