Martin Kramer, brilliant historian that he is, has described compellingly how David Ben-Gurion used the crisis of May 1948 to establish civilian control over the future Israel Defense Forces (IDF); it was not the least of his gifts to the new state.

I do not quarrel with Kramer’s basic assertion that Ben-Gurion was more optimistic about victory in the war than he let on to his associates in the People’s Administration, Israel’s cabinet-in-waiting, or than he allowed others to let on. What may be added, however, is a bit more context.

Ben-Gurion was, first of all, no naïf about military affairs. As anyone knows who has toured his house in Tel Aviv, it was filled to overflowing with works of military history. In 1947, moreover, he had conducted, and recorded in his voluminous diaries, a detailed study of the military preparedness of the Haganah, the Jewish armed force of the pre-independence yishuv—and he found it lacking. Thus, his campaign for civilian control over the military—in practice, his own control as the new state’s prospective prime minister with responsibility also for the defense portfolio—was never going to be simply an assertion of his personal will, although that was undoubtedly present. His actions reflected mature judgment as well.

Romantic conceptions of Ben-Gurion’s statecraft can miss this crucial point. He did not only believe; he also calculated, and his reservations about the capacities of the Haganah had several roots. For one, particular thing, he mistrusted and was dismayed by the political and ideological leanings of the Palmaḥ, the Haganah’s elite strike force; by its members’ adherence to small left-wing parties (soon to be folded into the larger and more threatening party of Mapam); and by its conceit, which occasionally went so far as to displaying reverent photographs of Stalin. Although he felt he needed the Palmaḥ in order to take down his rivals on the political right, who had their own formidable if small military force in the Irgun Tsvai Leumi, later he would use a crisis in the 1948-49 war of independence to smash up the Palmaḥ’s separate headquarters.

His view of the Haganah itself was somewhat more complex. He believed that it had been optimized to fight the local Arab population rather than the armies of Arab states; and he thought it self-absorbed to a dangerous if not fatal degree. “The [Haganah] sees itself as an end and not a means,” he said in a famous speech to his colleagues in June 1947.

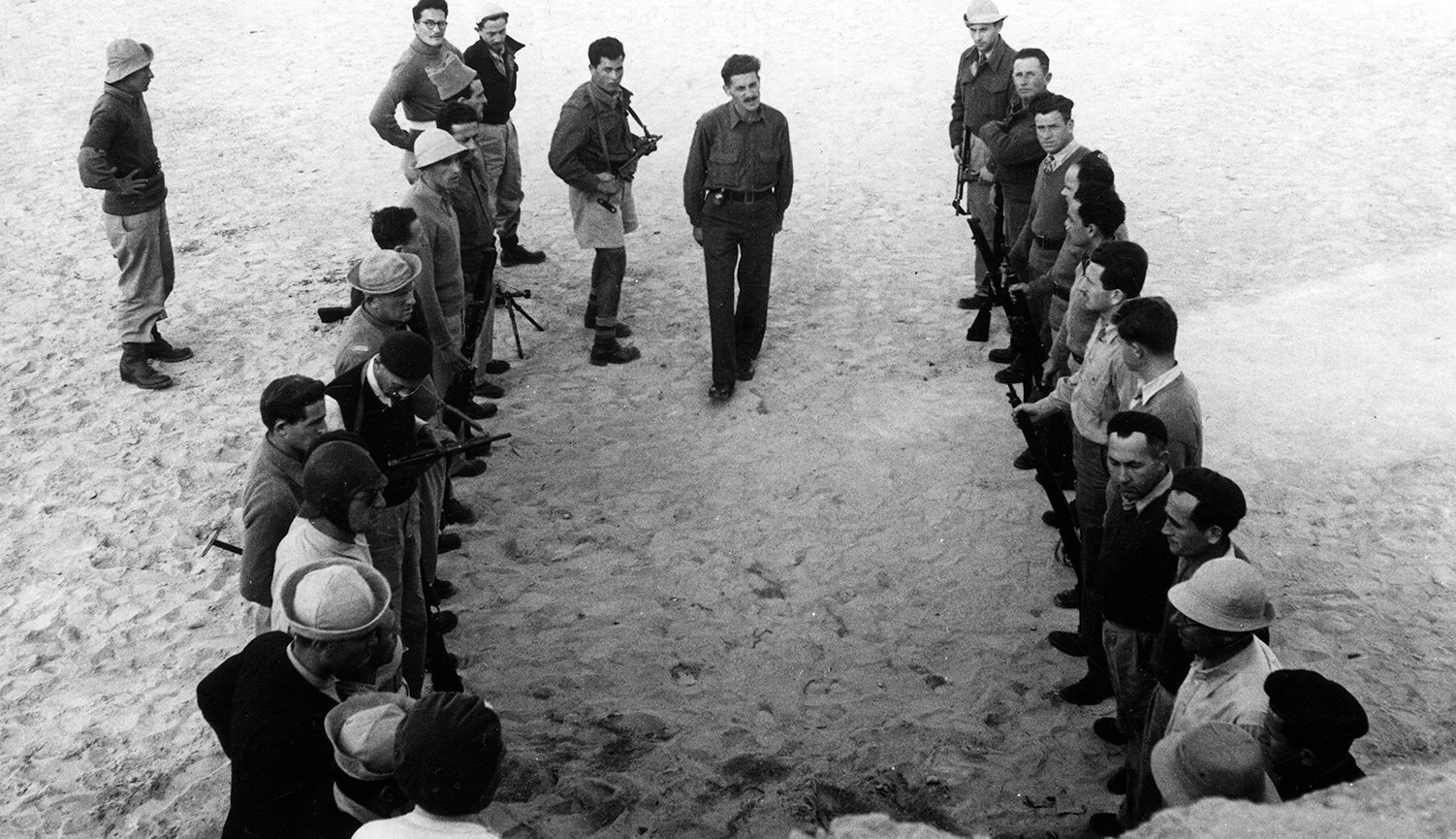

Perhaps most importantly, he doubted the military judgment of the Haganah’s officers. “They don’t have real military experience, and they don’t want it,” he said in the same speech, whereas he had at hand many individuals who he knew did possess such experience: namely, the thousands of Palestinian Jews who had served in the British Army during World War II, and the smaller but still substantial number of volunteers from abroad (many but not all of them Jews) who were similarly veterans of the world war. By some in the Haganah, strange as it may seem, the Palestinian Jewish veterans were seen as untrustworthy, having ostensibly “deserted” their homeland to fight for a foreign army; of course, as the future would show, in fields as disparate as signals intelligence, logistics, and aerial combat, their commitment and expertise proved invaluable.

Ben-Gurion forced an unwilling Haganah to call up and absorb these veterans, whose experience was put to use in building a regular army; in the years after independence, he would turn to them again to lead and shape the IDF. In 1948-49, the Haganah and the Palmaḥ, along with elements of the dissolved Irgun, the British Army veterans, and the overseas volunteers possessed all the necessary components of a real army.

Ben-Gurion fully understood something else as well: once independence was declared, constraints on overseas supply would disappear. And once that happened, the imbalance in weaponry could be corrected, as indeed it was. By the latter phases of Israel’s war of independence, the IDF had fighter planes (some of them, irony of ironies, a variant of the German Bf-109 built in Czechoslovakia), machine guns, artillery, and all the other necessary paraphernalia. An elaborate acquisitions network overseas poured in large quantities of materiel, even as Israeli manpower resources grew with the accretion of immigrants of military age who in many case had undergone at least rudimentary training abroad.

To be sure, the Arab states had their own armies, but, with the exception of the small Jordanian Arab Legion, not very good ones. And an arms embargo imposed on the region by the great powers disadvantaged them more than it did the Israelis. In some ways, thanks to their own small but respectable indigenous manufacturing base, a sophisticated underground acquisition effort abroad, and the all-important arms deal with Czechoslovakia during the brief window of Soviet support for the Jewish state, the Israelis were actually better positioned than their opponents.

Moreover, the intelligence organs and diplomats of the state-in-waiting possessed an acute understanding of their Arab counterparts. In many cases they knew them personally, were familiar with their internal rivalries and suspicions, and understood how unlikely it was for the Arab states to succeed in concerting their military efforts. Israel benefited as well from covert help from European allies, in particular Italy and France, both of whom were willing to turn an occasional blind eye to activities whose strict legality was in doubt. Something similar also held true in the United States.

Finally, as Ben Gurion realized, Israel had an additional advantage: geography. The Arab armies, unused to expeditionary warfare, lacked the logistical infrastructure to feed and sustain forces in the field. Israel, by contrast, was fighting along internal lines and could move its forces quickly from theater to theater. Often, indeed, it was fighting in its own cities and villages—which, although terrifying in one sense, was also a source of strength, imparting that extra bit of motivation that comes from having one’s back to the wall. Up against the class-ridden, inexperienced, and poorly disciplined Arab armies (again, excepting the Arab Legion), the Jews could and did stand.

In other words: what Ben-Gurion knew was that if the new state could declare independence and then hang on through an admittedly perilous early phase, it would grow considerably stronger while its opponents might well become weaker. And so it proved to be.

The first month was extremely difficult, with serious losses. But during the truce that followed, Israel gained steadily in strength, and thereafter the war’s momentum swung to its side. By the end, Israeli units had penetrated Sinai and could have taken the West Bank as well had they wished to.

And then, of course, Ben-Gurion was an outstanding war statesman—as outstanding in his way, given the size of the stage on which he operated, as Churchill on his much larger stage. An indomitable spirit, a powerful vision, and rhetorical gifts combined to help make him so. But we should not forget that he was also a shrewd judge of people and things, a realist rather than a dreamer, a calculator as much as a prophet armed. All of these qualities together are what made him truly great.

More about: 1948, David Ben-Gurion, Haganah, IDF, Israel & Zionism, Israeli War of Independence