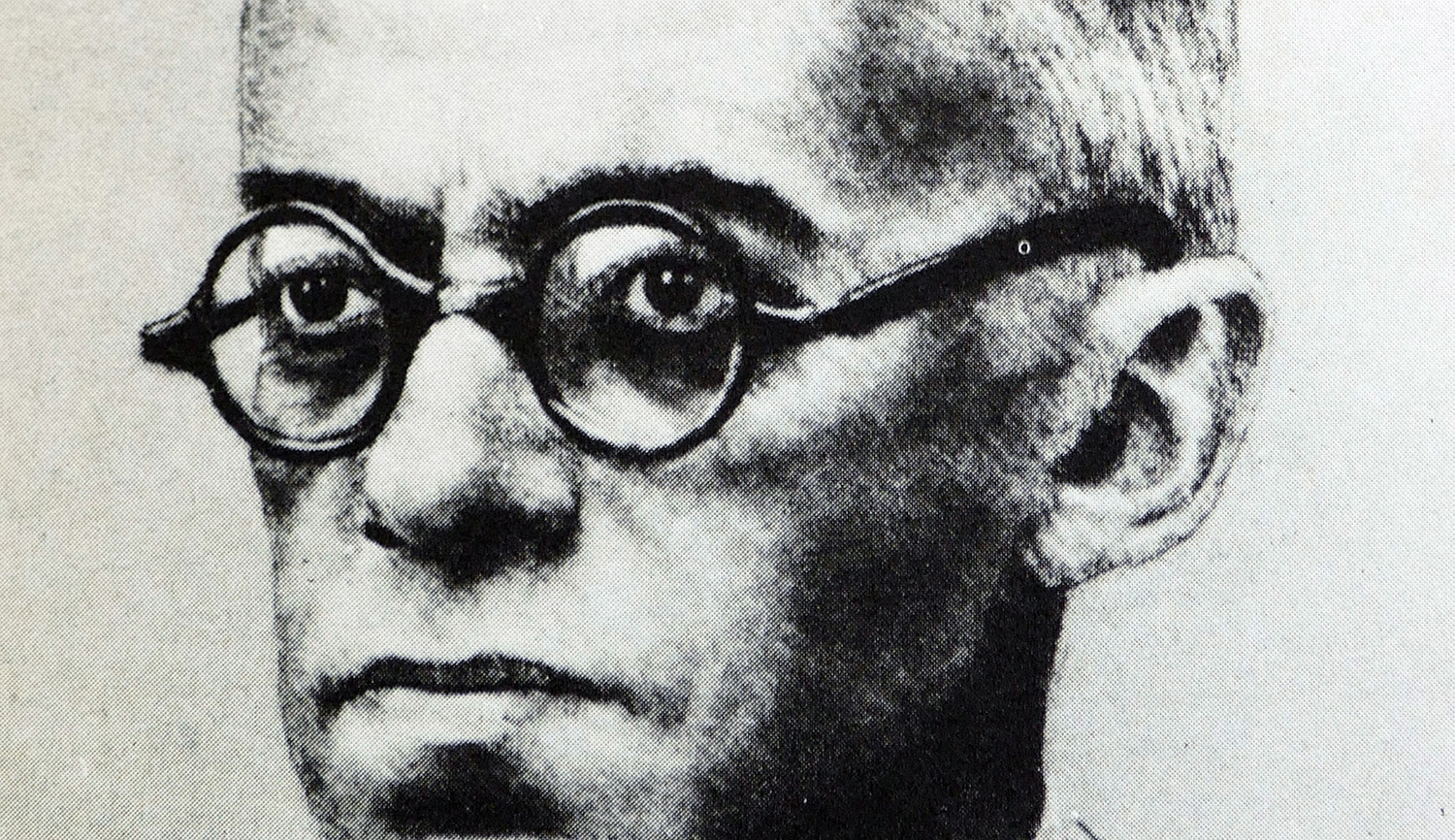

In contemporary Israel, as Avi Shilon points out in his thought-provoking essay in Mosaic, the name of the great Zionist leader and strategist Ze’ev Jabotinsky (1880-1940) offers something for almost everyone. A “seminal figure in the history of the Israeli right,” the inspiration of today’s Likud party, and a prolific author, he left behind a huge corpus of quotable thoughts and ideas. These, however, are so rich in nuance that it’s easy for any two people to reach contradictory conclusions about what he really believed and meant.

Consider, for example, the central topic of Shilon’s essay: Jabotinsky’s stance toward religion. Following Hillel Halkin, the author of a recent biography, Shilon claims that, in his last decade, Jabotinsky edged away from secularism toward a reconciliation with religion and Judaism. In doing so, he set the stage for an alliance between his hitherto secular Revisionist movement and Israel’s traditionalists, an alliance that Menachem Begin, his most important disciple, would subsequently leverage into Likud power.

As it happens, this is not so new an argument as Shilon makes it seem. In the 1960s, the journalist Isaac Remba, who decades earlier had been at Jabotinsky’s right hand, published an article making a similar claim. But then Jabotinsky’s son, Eri, promptly denounced Remba’s take as “total distortion.” “My father wasn’t religious,” the son wrote, “he simply didn’t believe in the existence of God.” Even after the rise of Nazism, when he urgently sought allies to fight for a Jewish state, the father still preferred David Ben-Gurion and the left. Only when spurned by the left, according to his son, did he turn to the Orthodox to fortify his dissident New Zionist Organization, an alliance led by the Revisionist movement. But even then, Eri concludes,

his interest in religion and the Orthodox was strictly practical and political. At the most, while in contact with these people, he began to take an interest in their deeper motives. It was no more than that.

In 2004 this debate would take an academic turn in a lengthy and learned essay by Eliezer Don-Yehiya, a Bar-Ilan University expert on religious Zionism. As against Eri Jabotinsky, Don-Yehiya denied that Jabotinsky’s late interest in Judaism was “tied mainly to ‘opportunistic’ considerations . . . to win electoral support within the religious public.” Rather, Jabotinsky underwent “a principled change in his attitude toward religion.”

But this, too, was hardly the final word. Arye Naor, head of the academic committee of the Jabotinsky Institute (and former cabinet secretary to Menachem Begin), put together an equally lengthy and learned rebuttal. “My conclusion,” Naor wrote,

is that for all his life Jabotinsky was a total agnostic. . . . His theological position never really changed and all his life he remained agnostic if not atheist, and in any event a complete epikoros [heretic]. . . . Only when it was a political necessity did he begin to interest himself seriously in religion.

So we have here a long-running debate. Still, for the most part, it is an internal debate among Jabotinsky’s disciples. In order to assume power, the secular Likud party had to ally itself with religious Zionists (and even non-Zionists). But how big a compromise was that? Those who seek to minimize it claim that Jabotinsky had “koshered” the alliance as far back as the 1930s. Those who think that, historically, the party has humbled itself before too many rabbis portray the compromise as a deviation from Jabotinsky’s own path.

Since Jabotinsky isn’t here to clarify his position, the question can’t be resolved. My own sense is that Naor has made the better argument, and that the case for the sincerity of Jabotinsky’s turn to Judaism—what Shilon calls his “mature thought”—is unconvincing. If that is the case, then Jabotinsky and Ben-Gurion weren’t all that far apart in their religious (un)belief, and were all but indistinguishable in the degree of their (non-)observance.

Needless to say, however, this didn’t prevent either one of them from cutting political deals with the faithful. Which leads us to a more interesting historical crux when the two men really did stand on opposing sides.

In the spring of 1920, as Shilon points out in his Mosaic essay, a debate ensued within the leadership of the yishuv, the Jewish community in British-ruled Palestine. The issue was whether (a) to reinforce or (b) to evacuate the defenders of Tel Ḥai, a Zionist outpost in the northern Galilee encircled by superior Arab forces.

At the time, Britain and France still adhered to the Sykes-Picot accord of 1916, which allocated the territory of the Galilee’s northern panhandle to France. But the French had been slow to put troops there, and the vacuum had been filled by marauding Bedouin, abetted by Arab nationalists fighting against France. Soon, the established Jewish town of Metula and the farming outposts of Tel Ḥai and Kfar Giladi found themselves in the midst of a Franco-Arab war, with almost no means of defending themselves. With each passing day, security deteriorated as hundreds of armed Arabs roamed the valley in search of plunder and French soldiers.

The debate over what to do about Tel Ḥai took place in Tel Aviv in late February 1920, at a time when Jabotinsky still sat amicably at the same table as other leaders of the yishuv. Speaking as a military man, he made this argument:

I believe that all those [Jewish settlers] in the French zone must be withdrawn. . . . I say now that with 200 men we shall not be able to defend our land. The danger is not that [people] will be killed; but their clothes will be stripped off them, they will be sent back [naked], and that will look ridiculous. Now there is talk of [sending] 500 men, but the Arabs have large quantities of arms, and 500 men are also not enough to stand against them. . . . I beg you, as colleagues, to tell the young defenders the bitter truth, and perhaps save the situation.

Ben-Gurion, for his part, argued the opposite:

If we flee in the face of bandits, then soon enough we’ll have to flee not only the Upper Galilee but all of Eretz-Israel. . . . There is great value in every one of our positions in the country. It is forbidden to flee any place that we’ve already conquered once, just as we won’t flee all of Eretz-Israel. Obviously, the circumstances are difficult, and there will be much suffering. But we will take this upon ourselves. Our Zionist obligation is to defend, and not abandon, any of our positions for as long as we can.

In this debate, Jabotinsky stood alone. All of the others—the Labor leaders Berl Katznelson, Yitzḥak Tabenkin, and the rest—preferred that Tel Ḥai hold out, and they resolved to send reinforcements. But, before their arrival, Tel Ḥai was breached by Arab marauders who killed Joseph Trumpeldor, the outpost’s charismatic leader, and five others. The survivors burned and abandoned the site, prompting the evacuation of nearby Kfar Giladi as well. It was a debacle, and it sent shock waves through the yishuv.

The events of Tel Ḥai soon became encrusted in heroic legend. Though much of it was purely mythical, of greater significance to us here is the debate that preceded the catastrophe. For there is a paradox, and it is plain to see: namely, that Jabotinsky’s call for retreat appears openly to contradict the ethos of “never retreat” that has long been associated with his name. “To die or to conquer the mountain” famously proclaims the anthem composed by Jabotinsky in 1932 for Beitar, the Revisionists’ youth movement. It ends by invoking Yodfat, Masada, and Beitar: three sites where, in antiquity, Jews had chosen to be captured or killed rather than surrender to superior Roman forces.

In the early 1930s, a chasm opened up between Revisionist and Labor Zionism, and Jabotinsky’s stance over Tel Hai became, for his opponents, a tool of recrimination. “We will struggle even when we know for sure that we will fall,” declared Ben-Gurion later:

Jabotinsky made the calculation that we would not succeed in defense, so it was better to abandon the place in advance. We said: don’t abandon, even if we knew we would not succeed. . . . I do not think we were wrong. What Jabotinsky saw as an expert was perhaps true: some comrades fell, the rest had to flee. The outpost burned down. But no one will say now that Tel Ḥai’s defense was in vain.

Jabotinsky, in response to such criticism, claimed that Tel Ḥai became a “last stand” only because the same leaders who rejected evacuation did too little, too late, to save Trumpeldor:

It was the duty of these people (and they also had the necessary time) to do one of two things: either send reinforcements or order Trumpeldor and his colleagues to evacuate the besieged area. If instead they left a handful of young men and women alone on a tiny farm, surrounded by several thousand well-armed Bedouin, surely there is someone to blame for this awful flippancy. Who is guilty?

True, Jabotinsky acknowledged, the defenders of Tel Ḥai had demonstrated great heroism. So, too, he commented mordantly, did many passengers on the Titanic:

But it is the duty of society to see to it that a ship doesn’t sink, houses don’t burn down, wars don’t break out. Tragedies are almost always beautiful and noble, and there is a moral to them, but all this can be appreciated only in retrospect. Never in advance. One must never place or leave people in situations that will inevitably end in tragedy.

Despite the incalculable value of Tel Ḥai’s heroic stand for the ethos of the yishuv, Jabotinsky added, if circumstances warranted he would adopt the same position again.

As a matter of tactics, or even strategy, it’s possible to see merit on both sides of the Tel Ḥai argument, and to express a reasoned preference for one over the other in the circumstances of the time. But that episode took place a century ago, in totally different conditions from those obtaining in the decades since Israel’s independence. Why has it remained relevant?

Arye Naor, an expert on all things pertaining to Jabotinsky and in the late 1970s a first-hand witness to Menachem Begin’s peace deal with Egypt, has connected the dots from past to present. The debate over Tel Ḥai wasn’t just tactical, Naor insists; it was ideological. While Jabotinsky had a “high regard” for the settlement cause,

in his view it was a means to another end: the establishment of a state. Settlement would help leverage Zionist pressure on Britain to implement the Jewish National Home in line with the principles of the Balfour Declaration, the meaning of which, ultimately, was the establishment of a Jewish state. The Labor movement [by contrast] saw settlement not as a means but as an end. . . . It was characteristic of Labor not to give up a single settlement, whereas it was characteristic of Revisionism, from Jabotinsky to Begin, to see settlements as a means to another end.

Having drawn a line from Jabotinsky to Begin, Naor then draws a complementary one from Tel Ḥai to the Sinai peninsula:

And so Begin, as prime minister, could give up Israeli settlements in the Sinai in order to achieve the peace treaty with Egypt. . . . The point of view begun by Jabotinsky and continued by Begin was that, in certain circumstances, it was permitted to give up settlements in order to achieve other objectives.

In addition to Begin, who in 1982 dismantled nineteen Israeli settlements in the Sinai, one could adduce here also Ariel Sharon, who spent 28 years in the Likud party and who in 2005 dismantled all 21 Jewish settlements in Gaza and another four in the West Bank. While Begin’s “other objective” was to achieve peace with Egypt, Sharon’s was to preserve Israel’s Jewish majority. In pursuing and justifying it, he quoted Jabotinsky directly: “The term Jewish state is certainly clear: it means a Jewish majority.”

And here we come upon a longstanding irony and another paradox. In the history of Israel, the dismantlement of settlements has been ordered only by the political heirs of Jabotinsky. In power, they haven’t even taken the step of annexing a settlement.

For this, they have of course come under attack—not from their opponents on the left, however, but from their political allies farther to the right, who charge them with betraying Jabotinsky’s legacy. This, for instance, is the bedrock of a recent 540-page indictment, by the far-right gadfly Aryeh Eldad, of five right-wing prime ministers from Begin to Netanyahu. To counter it, those in the Likud assert that they need no tutorial in the proper interpretation of Jabotinsky’s doctrines. And because, when it comes to national security, the crucial debates now take place largely on the right, nothing is so useful to all sides as an apt quotation from Jabotinsky.

For years, Zionists of all stripes in Israel claimed that the heroic stand at Tel Ḥai ensured the inclusion of the Galilee panhandle in the British mandate for Palestine, and later in the Jewish state. This claim was always suspect: the heroic stand ended in a panicked retreat, and that sort of outcome rarely produces territorial gain. But now we know for certain that the claim is a myth; nowhere in the records of the Anglo-French negotiations that fixed the northern border of Palestine is there a single mention of Tel Ḥai. As any student of Jewish history knows, events that loom large and consequential for the Jews often go unremarked in the annals of the great powers.

But if the skirmish at Tel Ḥai had no effect on the fixing of Israel’s northern border, the stand Jabotinsky took before its fall may well have helped to fashion its southern border. Whether Jabotinsky would have told Begin and Sharon to pull Israel back from Sinai, or from Gaza, is just speculation. But we know for sure that both of them believed, and averred, that he would have nodded his approval.

Could this mean that, since Israel’s eastern border has yet to be fixed, Jabotinsky may still not have spoken his last word?

More about: David Ben-Gurion, Israel & Zionism, Joseph Trumpeldor, Vladimir Jabotinsky