I am grateful for the excellent comments by Eugene Kontorovich and Yonatan Green to the final installment of my seven-part series on Israel’s declaration of independence.

Basically, these two learned legal authorities focus on what the declaration isn’t. The declaration isn’t a political map of the borders of Israel, and it isn’t a credible substitute for a constitution; its drafters, as I show in my last essay, never intended that it be either of those things. Moreover, in announcing that a constitution would be produced separately and at a later date, the declaration explicitly disavows any pretense to be one.

In brief, on each of these basic points the three of us are mainly in complete agreement. Not only that, but we also agree on the importance of underscoring these facts. The reason? Because, as I have documented and as Kontorovich and Green concur, for some time now the Supreme Court of Israel has been, in Kontorovich’s words, “treating [the declaration] as a constitutional document—that is, as a basis to overturn Knesset legislation”: a move that finds no warrant whatsoever in the declaration itself.

Since the three of us agree on these facts, how to keep our exchange interesting? Let me raise a few (minor) points of difference before drawing conclusions.

One of the underlying principles of the declaration is that the state of Israel is not a successor state to the British mandate for Palestine. Rather, it marks a restoration of the Jews to the sovereignty that they exercised in antiquity. In this view, the British mandate was but one more episode in a long interlude of foreign rule, now ended—but that end involved no transfer of power. Israel arose in the vacuum created by the termination of the mandate.

This somewhat undermines Eugene Kontorovich’s argument about the new state’s borders. These, he writes, “would be governed by the same rules as [were] other countries, . . . inherit[ing] the borders of the last top-level administrative unit in the area.” This is the legal principle known as uti possidetis juris (“as you possess under law”). In this view, Israel automatically assumed the borders of British mandate Palestine. Kontorovich and I have debated this subject in Mosaic before, so I will be succinct here. In actuality, independent Israel never recognized the mandate borders and never claimed them for itself. It was born without borders, and without any commitment or claim to any specific borders—neither those of the UN plan of 1947 nor those of the mandate drawn earlier by Britain (and France) in the 1920s.

The Palestinian Arabs took an entirely different approach: they did claim the mandate borders. Although Kontorovich writes that the Palestinians waited to stake their claim to sovereignty for a full 40 years, “until the height of the [first] intifada in 1988,” that is not the case.

In fact, on October 1, 1948, the All-Palestine Government, then in Gaza, declared a “free and democratic sovereign state” of Palestine. Six of the seven Arab League member states recognized it. The declaration, conveyed to the United Nations, asserted “the full independence of the whole of Palestine as bounded by Syria and Lebanon from the north, by Syria and Transjordan from the east, by the Mediterranean from the west, and by Egypt from the south.” The All-Palestine Government, as its name indicated, claimed to inherit all the borders of mandate Palestine—exactly what Israel’s declaration of independence did not do.

I daresay that Ben-Gurion hadn’t a clue about uti possidetis juris. He was guided by another principle: each Arab rejection of peace and each Israeli sacrifice in war needed to be translated into a corresponding gain of territory for Israel. Since there was no prospect of peace, Israel’s declaration left border determination to the indeterminate future.

As Yonatan Green reminds us, Ben-Gurion similarly deferred constitutional debates to the post-war period (and beyond). The result of Ben-Gurion’s postponing was that, to this day, Israel has had neither a complete set of borders nor a completed constitution. The deficit is perpetuated by deep political disagreements over the final contours of Israel’s map and the final content of any Israeli constitution. In the absence of a consensus, partisan actors work to “create facts” in line with the actors’ own purposes. This has been the strategy of, on one side, the post-1967 settlement movement and, on a very different side, Israel’s legal establishment. Each spreads the idea that, to all intents and purposes, Israel already has either a certain map or a certain constitution, each of which the contending parties strive to shore up in hopes of its evolving into a permanent reality.

Zionism itself owes everything to this strategy. It was, in fact, a primary mode of operation throughout the pre-state period as the Yishuv’s leaders exploited every vague provision in the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in order to build a de-facto state within that mandate’s remit. Ironically, the habit of building states-within-the-state has continued long after independence.

Does the declaration of independence provide guiderails for this competition? Most Israelis think so. They believe the declaration does set the key parameters: namely, the state is Jewish; its citizens are equal; and it seeks peace. Were Israel ever to veer away from any one of these, it would betray the vision that inspired its founding.

True, there are individuals, and even communities, who dissent from one or more of these principles. As long as they remain a minority, however, Israel will remain Israel. The declaration cannot be a constitution, for precisely the reasons so ably adduced by Kontorovich and Green: it was composed on the fly, it lacks specificity, and it cannot be amended. But this is a working definition, and the work is not finished.

I do also want to take issue with the way Yonatan Green words one of his arguments. He writes that the declaration “was drafted in secret by a handful of powerful figures embedded in the Zionist ruling elite.” That may be one way of putting it, but I detect some undue asperity, much as if someone were to say that the American Declaration of Independence was drafted by a handful of rich plantation owners embedded in the white male elite.

In contemporary Israeli politics, the notion of a powerful and secretive “ruling elite” has been weaponized on the edges of the left and the right. But it doesn’t describe 1948. The leaders who finalized the declaration started out as immigrants from Russia’s empire who on arrival became hardscrabble pioneers. They worked, for very little compensation, in voluntary Zionist organizations or in government offices headed by British officials. They weren’t yet a “ruling elite”—the British played that role—and they certainly weren’t powerful. They even lacked the power to open the gates of their “national home” to Jewish refugees, and were punished for trying. Less than two years before he became a key drafter of the declaration, Moshe Shertok (Sharett) was arrested by the British and imprisoned for four months.

In other words, the drafters were far closer to the people than are today’s Israeli politicians. Public trust in the Knesset hovers at 20 percent. Four times as many Israelis trust the IDF; twice as many, the Supreme Court. Indeed, this may help explain much of the lasting allure of the declaration: Israelis have a higher regard for the people who wrote it than for the politicians they now elect to office. (Readers with strong constitutions of their own may consult the many reports of politicians’ high living, vulgar behavior, and venal corruption.)

Why do the drafters of the declaration seem so special? Well, they were. They had a vision. It emerged from living their entire lives—up to May 14, 1948—under regimes that oppressed Jews. This applied not just to tsarist Russia but also to British Palestine in its later years. They had been freshly seared by the Holocaust, and they now faced an onslaught by the entire Arab world. They had a heightened sense of history, they craved sovereignty, and they took nothing for granted.

In forging a state (and an army), they triumphed so spectacularly that they did become a powerful ruling elite. But that came later. The declaration’s enduring appeal thus arises in good measure from a nostalgia for past leaders of a higher caliber. To cast these figures as a slightly sinister clique, imposing their will on the Yishuv, is a misreading. Most Israelis have come to see the declaration as the expression not of a “ruling elite” but of an entire generation.

That generation also included the Revisionist right. Menachem Begin, then the head of the Revisionists and of the Irgun, its paramilitary arm, wasn’t in the Tel Aviv Museum when Ben-Gurion declared independence. But three members of the Union of Revisionist Zionists (Hatsohar)—the organization and party founded by Ze’ev Jabotinsky in 1925—did sit on the People’s Council and signed the declaration. One of them, Zvi Segal, had been exiled to Eritrea by the British for his role in the Irgun. In the debate over the declaration, another of them, Herzl Rosenblum (Vardi), would explain the Revisionist position to the People’s Council:

We don’t want to search for flaws and propose amendments on top of amendments. Had we been the drafters, perhaps we would have formulated some points differently. But here it is before us, and we are fully ready to accept it, along with other members of the Council.

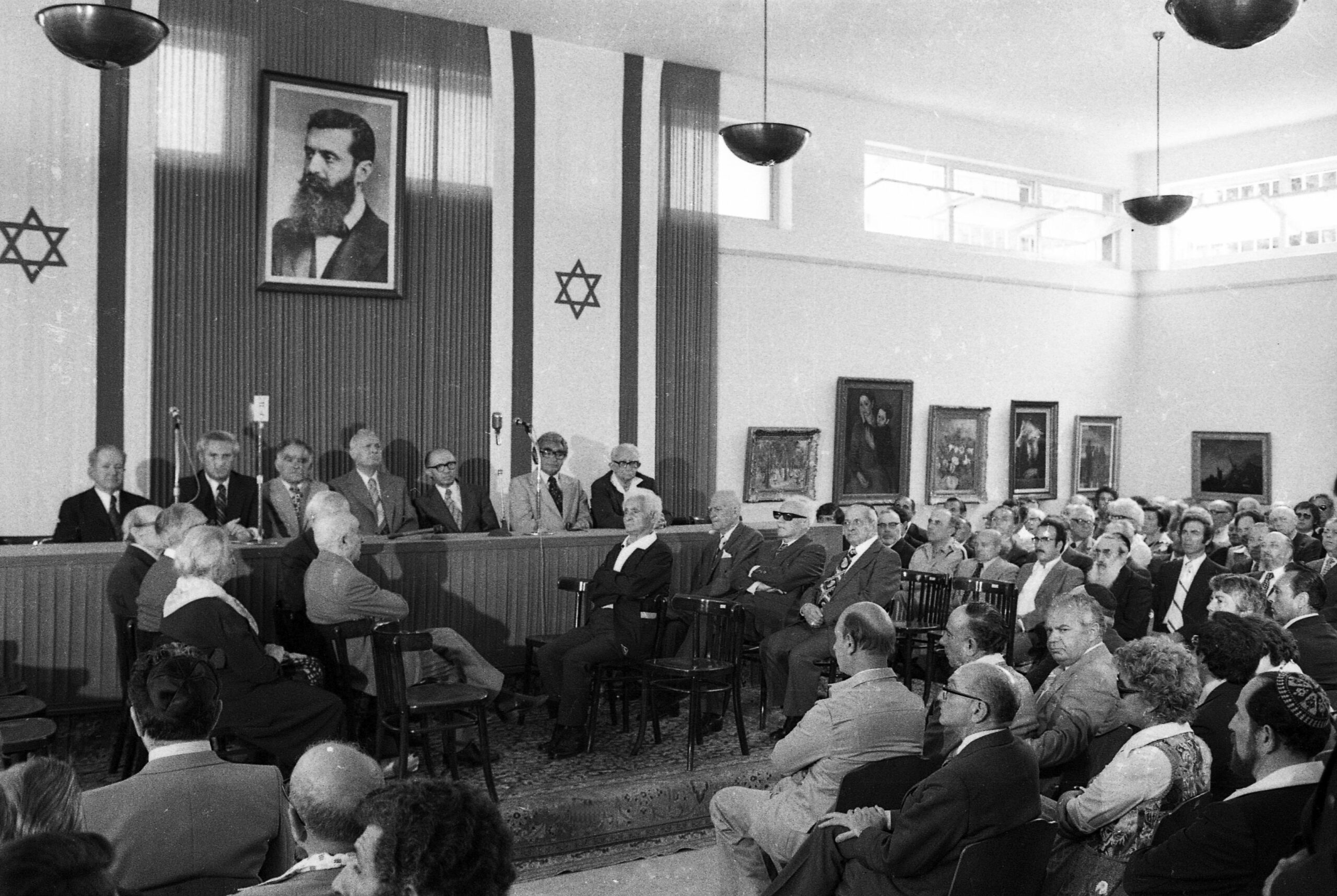

Menachem Begin not only accepted the declaration, he celebrated it. In 1978, on the 30th anniversary of the state, Independence Hall hosted a reenactment of the declaration ceremony. Begin, now Israel’s prime minister, sat on the dais; so did Yitzḥak Shamir, former commander of the Leḥi underground, now speaker of the Knesset. The hall filled with the recorded voice of Ben-Gurion reading the declaration. Begin, standing where Ben-Gurion had stood, gave a speech, describing the declaration as “moving and stirring.” Hundreds milled outside, just as they had done 30 years earlier.

On the state’s 70th anniversary, in 2018, Benjamin Netanyahu, head of the conservative Likud party and longtime prime minister, convened a festive cabinet session in Independence Hall. The State Archives brought the independence scroll for the occasion. Afterward the cabinet, formed largely of Likud ministers, stood on the steps of Independence Hall and sang Hatikvah.

These Likud leaders, heirs not of Ben-Gurion but of his nemesis Jabotinsky, embraced and celebrated the declaration as Israelis—proving once again that the declaration remains unsurpassed in its capacity to unite. Its words capture the spirit not of a person or a party but of a people. Precisely because Israel is so divided, the declaration still has a crucial role to play in reminding Israelis of their shared purpose. It is not a constitution; not by a long shot. But it is made of the stuff that belongs in one.

More about: David Ben-Gurion, Israel & Zionism, Martin Kramer on the Israeli Declaration of Independence