Why do they hate us? And what are we going to do about it?

Those questions were asked a lot in the United States in the years after 9/11. They have also been asked a lot by Jews over many, many more years. There may even be some similarities in the two groups of questioners, because there are certainly some similarities between the hatreds they inspire.

Contemporary anti-Americanism strangely resonates with contemporary anti-Semitism (and anti-Zionism). Both imply a distrust of the sense of national mission that America once projected and that Jews (and Israel) have represented. These are atypical nations—one created ex nihilo, lacking long and tested traditions (by world standards), the other anciently formed but until very recently (when it too seemed to arise anew ex nihilo) defined solely by long and tested traditions; one seeming to construct itself out of no particular people, the other out of a single miniscule people.

Yet both have insisted on their national prerogatives, regularly disrupting the progressive, utopian dream of transnational universalism. What gives them the right, the haters ask, to claim any exceptionalism? Why should others have to give way before them when they are so resistant to convictions endorsed by the enlightened citizenry of the world’s united nations? Their subterranean machinations have corrupted modernity.

Given their excessive and regressive nationalism, their preening self-interest, their brutish exercise of power and their hypocritical claims of virtue—so the haters proclaim—every failing and flaw just proves, all the more, their illegitimacy. Oddly too, these accusations of crude nationalism and power and manipulation thrive even when they are being made by groups who think nothing of championing such matters—while claiming great virtue—for themselves. It a bit like the PLO once proclaiming that its ultimate goal was “a democratic state in all of Palestine,” seeming to scorn particularism and nationalism and winning much admiration for its generous stance.

In the meantime, it is often reassuring for many who dwell in these hated realms to try to anticipate such hatred and avoid it by minimizing whatever is thought to be inspiring it: nationalism, particularity, power, patriotic allegiance. Do you want to be hated less? The prescription is clear.

I exaggerate, but just a bit. And of course, there are complications, variations, and even cases in which one hatred (anti-Semitism/anti-Zionism) finds an increasingly comfortable home in the object of another hatred (anti-Americanism). In any case, similarities between the two accused nations certainly don’t guarantee that both will possess the same goals and fantasies, and certainly don’t guarantee that an American-made form of entertainment will reflect the world as seen by Jews or Israelis. As Rick Richman shows in his fine essay, it certainly hasn’t in the past. America sees Israel through its own eyes. Exodus is not a film that Israelis would make about their founding (though it isn’t even a film that Hollywood would now make). Munich seems more about American attitudes than Israeli history. And after reading this essay, no one can now see Top Gun: Maverick without being aware of its direct allusions to the missions of Israeli fighter pilots. Incidentally—and curiously—the 1986 film, Top Gun, was based on a 1983 article in California magazine, written by an Israeli, Ehud Yonay (it had nothing to do with the reactor raids Rick Richman discussed). And last summer, the author’s Israeli widow and son (Ehud died in 2012) sued Paramount, claiming that the new movie violated the article’s copyright, which had reverted to the family.

But I’d like to give the screw yet another turn, partly because I feel less sanguine than Mr. Richman does about the implications of his analysis. The American perspective that takes form under Hollywood’s lens is very often knit up in the reactions I’ve outlined above: a defensive retreat from these identities even as they seem to be embraced, particularly when Hollywood turns its attention to Jews. From the name changes of studio executives and their stars to films like A Gentlemen’s Agreement and yes, Exodus and Munich, there is something else going on. I’ll focus on Steven Spielberg, beginning with Munich. Let me review the case.

In the film, Avner, the Mossad assassin asked by Golda Meir to avenge the massacre of Israeli athletes at Munich, ends up disillusioned. He believes that the assassinations will make terrorism worse and declares: “There’s no peace at the end of this.” But as Mr. Richman points out, none of this appears in the book the movie draws upon, George Jonas’s Vengeance: The True Story of an Israeli Counter-Terrorist Team. Aside from Avner’s words cited by Mr. Richman, Mr. Jonas points out that Avner has “absolutely no qualms about anything they did.” There is also no other evidence for Mr. Spielberg’s portrayal of Mossad agents doubting their mission. The movie announces it is “inspired by real events,” but it more powerfully inspired by its own ideological convictions.

And yes, as Mr. Richman points out, one reason for Mr. Spielberg’s distortions had to do with his views about the United States. Avner’s declaration that there will be no peace as a result of these policies is made with the World Trade Center in the background. The words are meant to refer to its (future) destruction and the American response. In a 2005 interview, Mr. Spielberg claimed that by studying the doubts and “ethical qualms” of the Mossad agents, “I think we can learn something important about the tragic standoff we find ourselves in today.”

But Mr. Spielberg’s assessment of America is itself strained and his view of Israel may be even more severe. Many of the film’s details suggest that Israel is the primal cause of its own problems, perhaps even the primal cause of the 9/11 attacks (as suggested by the film’s final image). One Israeli agent points to an increase in terror around the world as a result of their mission: “All the blood comes back to us.” And because the film eliminates any historical context—including the 1972 attacks Mr. Richman reviews—these assassinations are presented as primal acts of escalation.

Make no mistake: the film may condemn the terrorists’ acts, but it gives credence to their cause. It goes along with the widely-held supposition that terrorism is—however extreme—a response to gross injustice. The “root cause” of terror is the wrong that preceded it. In fact, terrorism is proof of injustice. Even al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks were said to be examples of the “chickens coming home to roost,” a response to American malfeasance. The more extreme the terror, the more gross the injustice (a verdict the suicide bomber wants made clear). Note though that this interpretation is only applied to acts of left-wing terror. It is never applied to terrorism associated with the right (like the Oklahoma City bombing, or attacks on abortion clinics). The immense success of terrorism as a tactic has been due to this injustice theory of terrorism. It is implicitly endorsed by Munich. In other words: we have brought on terror by our sins.

There is also a real queasiness about Israel in this film. What kind of response to attacks could possibly avoid the “cycle of violence” accusation? A United Nations resolution? If there are any counterattacks, there are bound to be arguments (and they continue unabated about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan). But the film’s overall perspective makes any kind of violent response seem as if it were a descent into nativism and nationalism, and a rejection of universalist ideals. That must be avoided or more attacks will come. A safe space must be created.

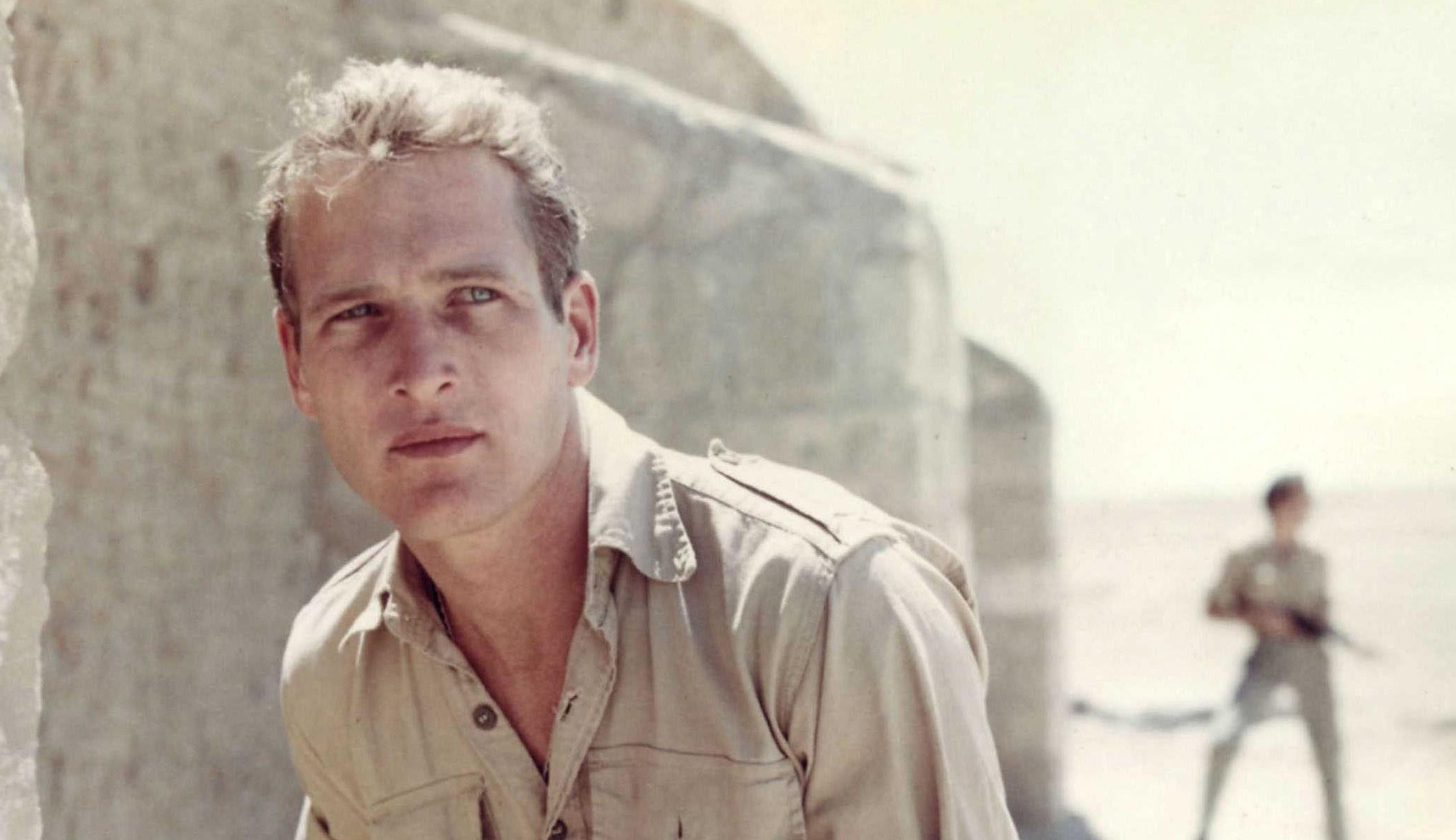

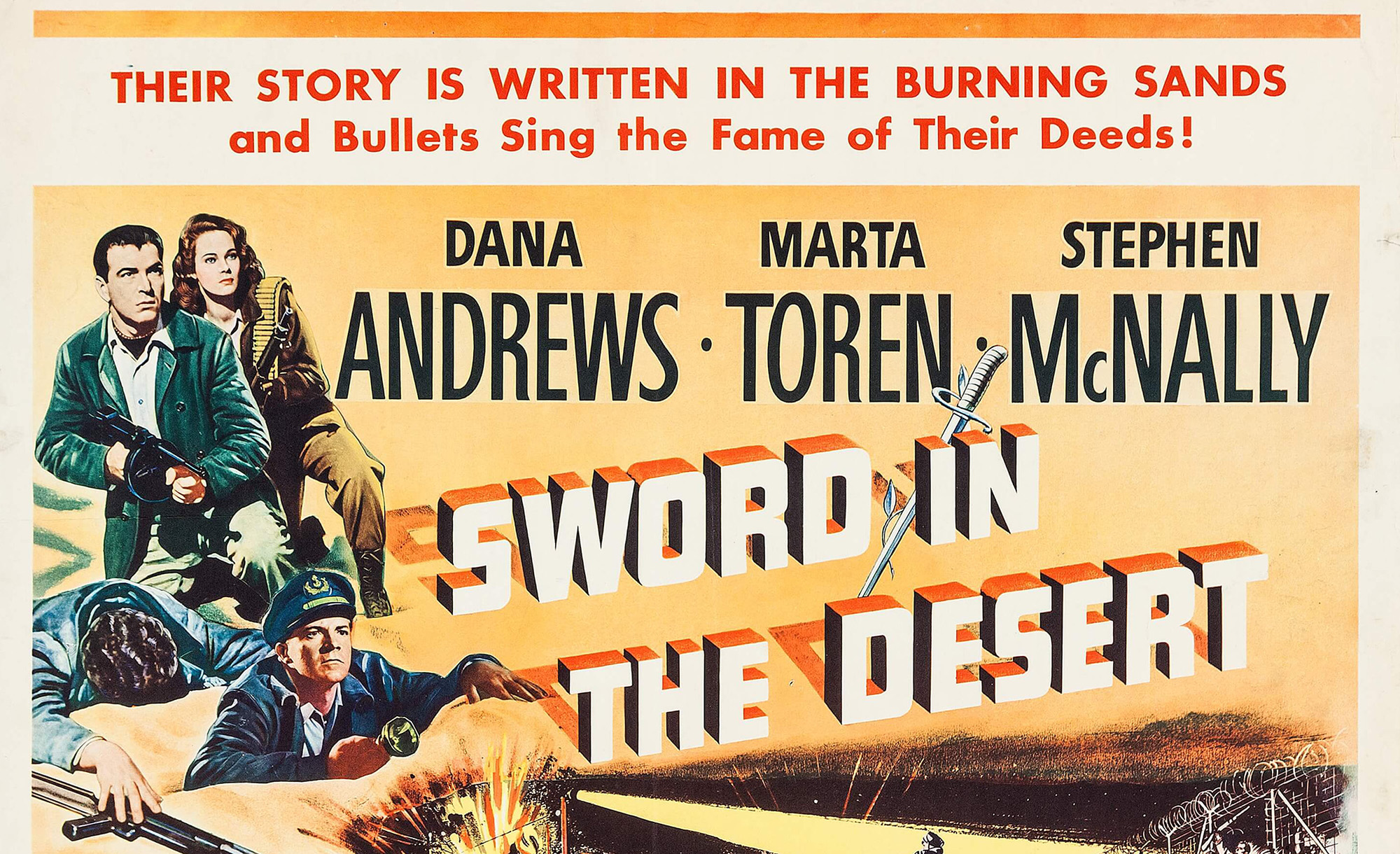

This attitude may even be latent in the ending of Exodus described by Mr. Richman when an Arab leader and a young Jew are buried together in a single grave as the Arab war on the newly-declared state begins. Ari Ben Canaan (Paul Newman) delivers a joint eulogy. I doubt there is any example of such a burial on the day the Arab nations attacked, announcing genocidal intentions. Its invention represents a fervent wish by the movie creators that there be an eternal union. So fervent is this wish, that religious rites for either of the deceased are simply jettisoned for an absurd sentimental symbolism. This is a desire for universalism with an American twist. But it requires an inability to see what is staring you in the face.

It is also a retreat from the theme of the movie itself and alien to the character of Ari Ben Canaan. He understood the nature of enmity and had few illusions about what was about to take place. The scenes where the children of the kibbutz are carefully drugged, put to sleep, and then carried to a presumably safe place are based on what Kibbutz Manara (on the Lebanon border) really did do with its children, who were carried off sleeping in vegetable crates because of imminent Arab attacks. But the film’s eulogistic ending almost seems like a retreat, as if there was a fear of showing too much Jewish particularism—a particularism that might engender further hatred. Excessive adherence to a Jewish identity or any kind of endorsement of a warlike stance—as the Irgun scenes seem to suggest—would not end well. It is safer to act out a wish for harmonious togetherness, even in death, as a kind of assimilation.

This isn’t really a national solution; it’s a personal one. You embrace your own identity, but you aren’t seeking victory. You also try to stave off the hatred that might come if you have too much allegiance to those supposedly retrograde forces that identify you as a people or nation. If you can champion your identity without too much insistence, you survive and thrive. Being a Jew in this sense is a personal matter. This is, I think, the way Mr. Spielberg treats his Jewish identity in The Fabelmans, his new fictionalized autobiographical coming-of-age film. In high school, he is mocked, humiliated, and attacked by an anti-Semitic bully. Vengeance comes not through his identity as a Jew or finding fellow Jews, but through his activities as a filmmaker (his universalist stance). A similar approach was at work, perhaps, when Mr. Spielberg once tried to ameliorate the conflict in the Middle East by distributing 250 video cameras to Palestinian and Israeli children to share films about their lives. It is as if he imagined hatred and enmity to be the result of a misunderstanding, a lack of empathy, or at worst, crude insensitivity. In a recent interview with A.O. Scott in the New York Times, Mr. Spielberg associates contemporary anti-Semitism with “an ideology of separation and racism and Islamophobia and xenophobia” that has come “barreling back” and “encouraged more and more since 2015 or 16.” It is a creation of Trumpist populism and thus something reprehensible but also to be defeated by appropriate liberal and universalist opposition.

But there is one film—Saving Private Ryan (1998)—that seems to show the opposite of what I have been arguing. It begins with an excruciating (and brilliant) cinematic recreation of the D-Day landings on Omaha Beach, but the movie’s focus is on attempts to bring home a soldier from the frontlines whose brothers have all been killed. The film was credited with a renewal of patriotic feeling. Images of the American flag open and close the film. Isn’t nationalism being embraced here and not universalism? Isn’t it quite different from the conceptual retreat I was describing? Doesn’t this film suggest that not every enemy can just be undermined or placated or ignored? No cycle of violence here.

Ryan, though, is significantly different from earlier World War II films, even The Longest Day (1962), in which Allied foul-ups lead to disaster. The public justification for the war in those films was clear: this was a just and necessary fight, demanding private sacrifices for public good. That vision largely held, at least, until Vietnam transformed attitudes toward patriotism and war. Mr. Spielberg wanted to rescue the veteran from disrepute. But he didn’t really restore patriotism.

Instead, through the film, there is uncertainty about whether the quest for the last surviving brother—Private Ryan—is a mission worth pursuing given the risk. It is, we see, essentially a private mission, to spare the family any further grief. Tom Hanks’s character, who has seen much, gives it another private motivation: “If that earns me the right to get back to my wife, then that’s my mission.” Patriotism is privatized.

This also bypasses, by implication, identification with the nation. The approach is particular because it is personal; it is universal because every private person shares similar allegiances to self and family. But don’t confuse it with nationalism or patriotism. And it is many steps away from what would have been required to respond to the challenges in Munich or Exodus.

In this case, Top Gun: Maverick stands out as an exception—or an intriguing hybrid. It creates a vision of the personal and particular that is still capable of unembarrassed triumph. The resemblances to Israel’s attacks on nuclear facilities suggest that there is a national requirement for what needs to be done. The mission will indeed serve an essential public purpose. But in its pursuit, the movie still champions the individual—more than that, the rule-breaking individual, the maverick who ignores the chain of command, but whose devotion to the cause is inseparable from his determination to succeed, the type of hero and the type of victory that have long been associated with America and with Israel. Along with, of course, the hatreds of each that persist no matter how we might try to avoid them and retreat into the universal.